By Joshua Van Dereck

For three weeks in February 1862, Union Brig. Gen. Samuel Curtis led his Army of the Southwest on a 200-mile advance southward across the Ozark plateau in Missouri and into northern Arkansas. The February weather made for abysmal campaigning, pelting the men with snow and alternately freezing the primitive dirt roads or flooding them with mud. The advance was of such vital importance to the Union cause that Curtis’s department commander, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, ordered it to proceed despite the terrible weather. Halleck was committed to a series of grand river offensives aimed at striking into the heart of Confederate Tennessee. However, as long as Rebel forces lurked in southern Missouri within range of the vital base of St. Louis, any Union gains in Tennessee would be untenable. Halleck ordered Curtis’s army to advance through Missouri and drive out the Confederate forces, securing St. Louis as a forward staging base.

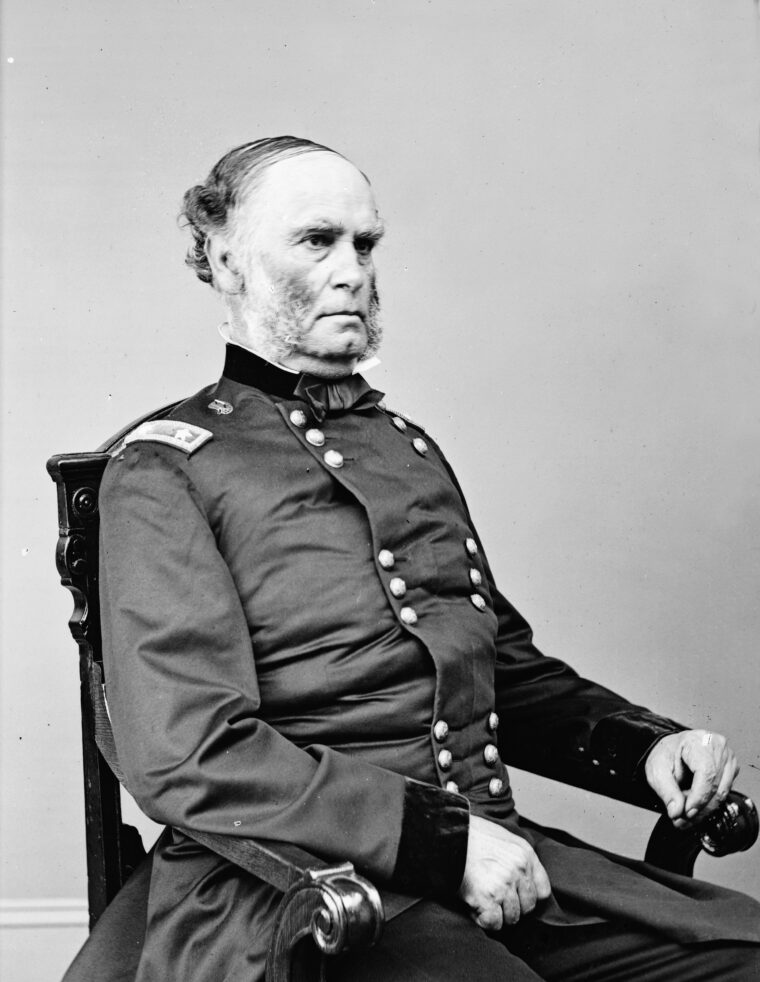

The task was a logistical nightmare, but Curtis embraced the challenge. A diligent and methodical officer, he was an 1831 graduate of West Point and had gained substantial administrative expertise through work as a civil engineer and congressional representative from Iowa. Appointed as field commander in Missouri in December 1861, he immediately set about organizing his command and preparing a base of military and commissary supplies at the railhead at Rolla, which would serve as the launching point for a tenuous wagon supply line for the upcoming campaign.

The force Curtis had at his disposal was small—four tiny divisions, adding up to about 12,000 troops from Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, Indiana, and Ohio. More than one-third of the men were foreign born, mostly German immigrants. They had rallied to the banner of the Union behind the appeal of the enigmatic Brig. Gen. Franz Sigel, who had served in the 1849 German revolution. Sigel was immensely popular with the German immigrant population. Seeking to defuse hostility between natives and immigrants, Curtis appointed Sigel second in command and gave him nominal charge of two of his divisions; both commanded foreign-born officers and troops made up mainly of immigrants. This segregated arrangement was not optimal, but it did help to ease tensions among the men.

Once Curtis was satisfied that his expeditionary force was thoroughly prepared, he began advancing southwest across Missouri. He moved steadily in the first weeks of February, driving Confederate forces out of their base in Springfield and toward the Arkansas border with surprising ease. In truth, the Confederates were stunned at the sudden appearance of the Union Army amid the wintry snow and were ill-prepared for a military confrontation. Under the command of former Missouri governor Maj. Gen. Sterling Price, a genial, portly officer of little experience or ability, the Confederates were a haphazard military force. Deficient in training and armed with a chaotic assortment of weapons, including shotguns, pistols, and old smoothbore muskets, they numbered about 7,000 men. Just across the border in Arkansas, however, was a substantial force of about 8,700 Confederate regulars—Texans, Arkansans, and Louisianans who were also waiting out the winter months in their camps.

Price decided to fall back toward these reinforcements, racing for the Arkansas border as fast as he could go. Scarcely halting for sleep along the way, Price’s men fell back 50 miles in less than 36 hours. They kept going southward past the Confederate base at Fayetteville, Arkansas, until their commander finally recovered his composure and allowed his men to collapse into bivouac.

Curtis pursued the retreating Confederates vigorously until his advance likewise ran out of steam for want of supplies. By then, he had covered some 200 miles, and his supply line was growing increasingly tenuous. Moreover, his army was showing signs of wear, having lost many draft animals to exertion as well as a goodly number of shoes and outer garments, which had worn away through repeated exposure to the elements. The army was also diminished in numbers, as Curtis had detached about 1,500 men to garrison captured towns and guard the supply line. None of this was overly disheartening—Curtis had already accomplished all that he had set out to do, having secured Missouri from Rebel incursions and even overrun a small portion of Arkansas.

During the last week of February, Curtis decided to pull back his men a short distance to the north to forage and rest. In the meantime, he sent repeated requests to Halleck for reinforcements and supplies. In true engineer fashion, he also sited a defensive position along a range of bluffs on the north side of a stream called Little Sugar Creek. There, the Union army would concentrate in case the Confederates somehow recovered their pluck and decided to launch a counteroffensive.

The Confederates Counter

That was precisely what the Confederates intended to do, although they did not know it yet. Price’s Missourians were still in the midst of recovering from their harrowing retreat, and their allies in gray were camped nearby, having scrambled to concentrate in the face of the surprising Federal advance. These forces were under the command of Brig. Gen. Benjamin McCulloch, an adopted Texan and notable frontier Indian fighter. McCulloch, a friend of the legendary David Crockett, was a veteran of the Texas War for Independence and the Mexican War as well as a former California gold prospector and representative for the Republic of Texas and to the United States Congress. As a military leader, he was a skilled administrator, tactician, and strategist, and he took good care of the men in his charge, a fact that showed in their high morale. Unfortunately for the Confederates, he and Price did not get along, and their squabbling had already led to a command change from above.

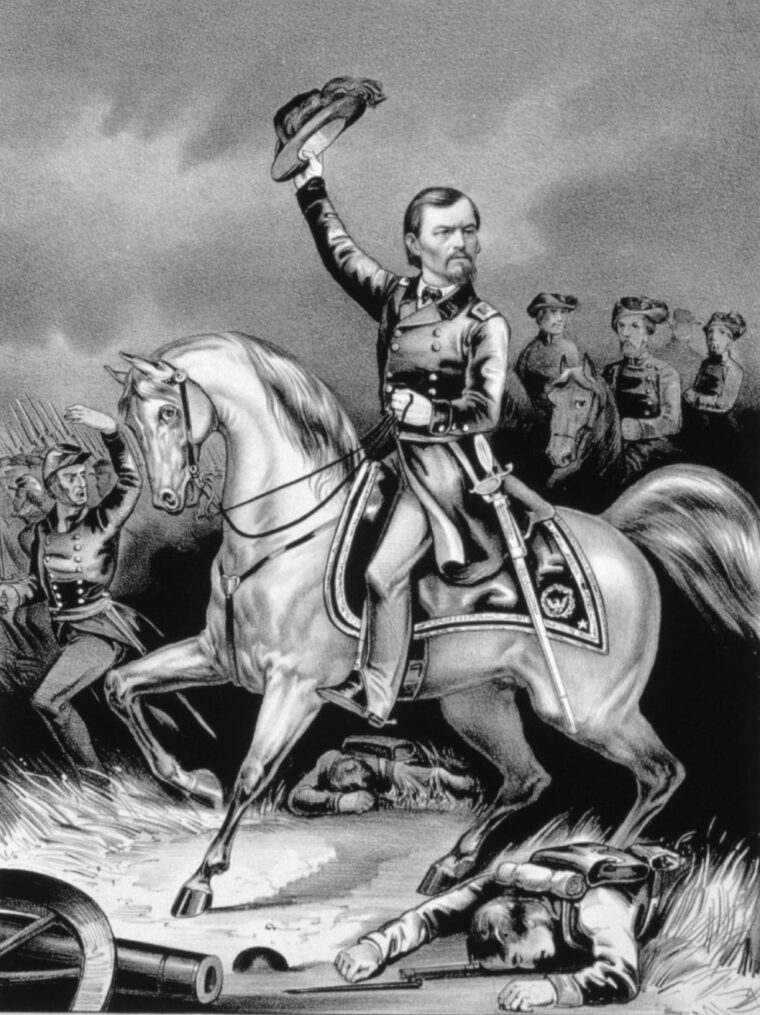

En route to take charge of the southern forces was Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn of Mississippi, a West Pointer who was a personal friend of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Van Dorn, who had served along the Texas frontier in the U.S. Army before the war, had all of the necessary credentials for high command, but not the temperament. Impetuous to the core, he had little patience for staff work, logistics, or careful planning. He was very ambitious, however, and was excited about the prospects for a decisive victory over Curtis. Summarizing his strategic vision in a letter to his wife, he wrote, “I must have St. Louis—then Huzza!”

Envisioning a grand advance by all available Confederate forces in the trans-Mississippi, Van Dorn instructed Price and McCulloch to prepare for immediate action, and he moved to reinforce them with a series of units of Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw Indians from the nearby Indian territory. Brig. Gen. Albert Pike of Arkansas was nominally in charge of these unusual soldiers, having negotiated treaties with their tribes at the beginning of the war. The 900-odd Indians who made their way east for the campaign were not particularly well organized or drilled. Nevertheless, Van Dorn assigned them to McCulloch, hoping that they would prove at least somewhat useful.

Hurrying by horse and boat to his new command, Van Dorn moved with such haste that he did not even pause to change clothes after taking an unfortunate spill in an icy river along the way. By the time he arrived, he was feverish. Undaunted, Van Dorn held a council of war with McCulloch and Price on March 3 and settled on an immediate advance against Curtis. The two Confederate commands, which Van Dorn jointly styled the Army of the West, would move out shortly after dawn the next morning, their ranks comprising a little over 16,000 men of all arms and 65 cannons. In preparation for the offensive, however, Van Dorn had not conducted any reconnaissance, nor had he familiarized himself with the quality or character of his troops. He scarcely knew the officers, and he made no inquiries into supplies. He ordered the men to travel fast and light, each taking a weapon, 40 rounds of ammunition, and three days’ rations—no heavy clothing or tents. The trains would contain one day’s emergency rations. After that, the men would have to make do by foraging.

Through the opening flurries of a blizzard, the Confederate army set out at a breathtaking pace on the morning of March 4. One soldier recalled, “It seemed as if General Van Dorn imagined the men were made of cast-steel, with the strength and powers and endurance of a horse, whose mettle he was testing to its utmost capacity and tension. Scarcely time was given the men to prepare food and snatch a little rest.” The army made good progress, but it was still two days’ march shy of the Federal encampment, and the men had to sleep that night without tents, huddled up and shivering in the snow.

“Almost Frozen and Starved”

The next morning, Curtis received word from his scouts (including future gunfighting legend James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok) that the Confederates were coming, and he immediately recalled the various detachments of his army to the position he had laid out previously along Little Sugar Creek. Van Dorn’s men toiled northward all that day and the next, skirmishing briefly with a rear guard that Sigel had inexplicably left behind in a dangerous position. By 5 o’clock in the afternoon of March 6, McCulloch’s cavalry had located Curtis’s defensive line, and Van Dorn called a meeting with his generals to discuss tactics. Nobody thought to mention the poor condition of the men, whose combat readiness had noticeably deteriorated during the course of the advance. As one Louisiana soldier recalled, “We arrived almost frozen and starved, having only one biscuit for breakfast that morning, and no prospect of supper.” The men had reached the bottoms of their haversacks and, lacking tents or overcoats, they had scarcely managed to sleep over the past few nights. The result was that straggling and bone-wearying fatigue would soon become major problems.

All the same, Van Dorn enthusiastically entertained various offensive proposals. All three generals agreed that a frontal assault on Curtis’s line would be foolhardy. McCulloch, who best knew the lay of the land in this part of Arkansas, suggested a limited turning movement of the Federal right wing. Such a maneuver might force the Federals to fight in the open. Van Dorn immediately seized on the proposal and expanded it into an enveloping maneuver with the whole army. He envisioned a spectacular surprise descent upon the Union position from the rear, severing Curtis’s communications and line of supply and destroying the Federal Army in detail before its commander knew what had hit him. To bring this to pass, Van Dorn ordered Price and McCulloch to move out at once with their respective commands on an all-night march around the Union position. Price and McCulloch were horrified. “For God sake,” Price said, “let the poor, worn-out and hungry soldiers rest and sleep.” McCulloch protested as well, but Van Dorn had made up his mind and would not be deterred.

After ordering the men to build an extensive line of campfires to fool Curtis into thinking they were staying on the south side of Little Sugar Creek, Price and McCulloch set out that evening on a long, slow, wearying march. “The night was one of intense severity,” one Arkansan recalled, and the column of soldiers was forced to halt repeatedly. First, they encountered Little Sugar Creek, and Van Dorn learned that his army contained no pioneers. The men had to fashion a makeshift bridge of hewn logs over the icy stream. Next, they found their path along the gravelly road blocked by a dense cluster of felled trees that Curtis had arranged to discourage just such a movement as the Confederates were attempting. Price’s Missourians in the van struggled through the night clearing the road. All the while, the Confederate column was thinning as starved and frozen men collapsed into desperate sleep. By the time the battle was finally joined, the Army of the West had only about 12,000 men in the ranks to engage Curtis’s 10,500 troops, and they were hardly in fighting condition.

As dawn approached, some of Price’s Missouri soldiers found crushed pieces of hardtack along the road where Union troops had dropped them. Watching his compatriots dig frantically for these unappealing cracker crumbs, one soldier remarked, “Who would have supposed that men ever get hungry enough to eat crackers that had been thrown in the dirt and run over by wagons?” An embittered Missourian replied, “When you get to supposing, who the devil would have imagined that an army would be marched all day and night without anything to eat, and then go into a hard day’s fight on an empty stomach?”

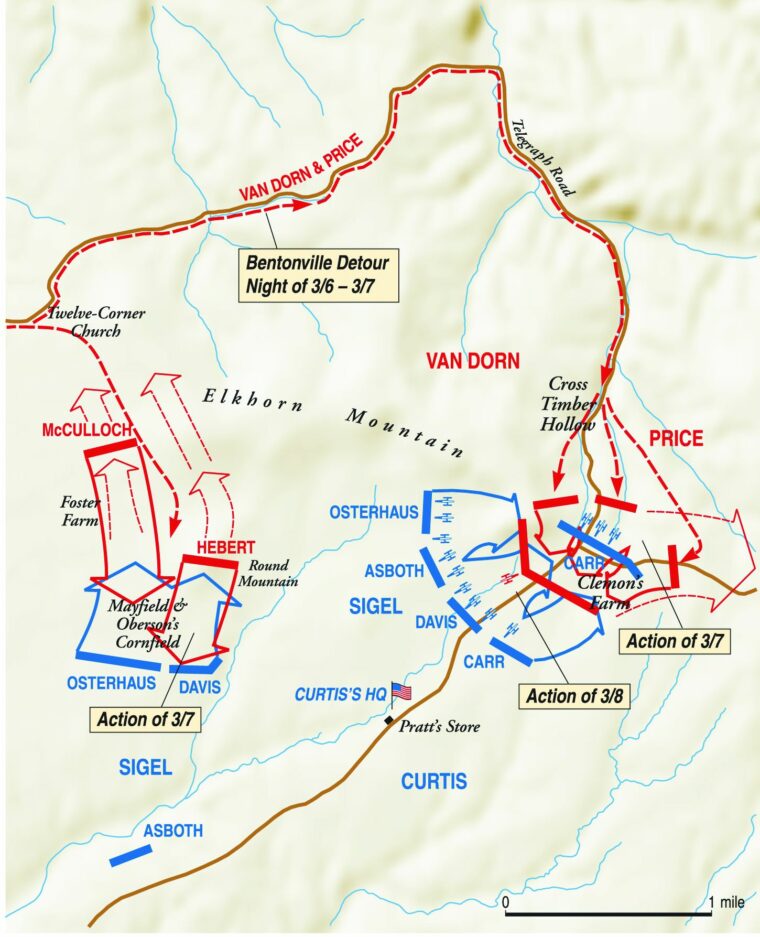

Van Dorn did not worry about such complaints. He hurried to the head of the column, reaching it at about 8 am on March 7. There he was delighted to learn that Price’s men had reached Telegraph Road and were firmly astride the Union army’s main line of supply. At this juncture, Van Dorn belatedly observed that the army was badly strung out along the road, an unfortunate occurrence that would delay the delivery of the blow he wished to strike. To hurry a concentration, he ordered McCulloch to turn his men south onto Ford Road, a shortcut that passed several miles to the west of Price’s column. McCulloch would then reunite with Price and Van Dorn near a hostelry called Elkhorn Tavern, from which place they would press south and give battle. In effect, Van Dorn was choosing to divide his army at the last minute in the face of the enemy. It was a decision that would have far-reaching consequences.

Two miles to the south at his headquarters at Pratt’s store, Curtis was in the process of evaluating intelligence reports detailing enemy movements around his right flank and rear. Federal pickets had first sighted Van Dorn’s turning movement at about 5 am, and it was becoming increasingly clear that a considerable body of enemy soldiers was approaching from the north. Curtis interpreted these reports as evidence that Van Dorn was trying to turn him out of his entrenchments—the very plan that McCulloch had proposed. It would be many hours before the Federal commander could actually bring himself to believe the improbable truth that Van Dorn had moved against him with his entire army.

At 9 am, Curtis assembled his division and brigade commanders for a council of war. Informing the various officers of the intelligence he had received, Curtis listened patiently to their responses. Some counseled retreat, saying that the army had no choice since its flank had been turned. Others urged aggression. Curtis heard them out and then announced that the Army of the Southwest would stay and fight. Not ready to abandon his entrenchments and bare his men to a potential spoiling attack, Curtis pulled a detachment of about 2,500 infantry, cavalry, and artillery from his line and sent it northward to investigate. In command of this force he placed the steady German, Colonel Peter Osterhaus, whom he instructed to locate the Rebels, determine their numbers, and, if possible, engage them. Osterhaus struck straight for McCulloch’s column on the Ford Road, where scouts had last seen the Confederates.

In the meantime, Curtis continued discussing the situation with Sigel and other officers. He was soon interrupted with the astounding news that there was also a column of Rebel soldiers due north on Telegraph Road, advancing southward toward Elkhorn Tavern. Flustered, Curtis immediately dispatched Colonel Eugene Carr, a pugnacious and argumentative subordinate, with a brigade of about 1,400 men to engage the enemy and drive them away. Curtis sent the other officers back to their various commands and settled down at headquarters to await further developments.

Van Dorn, who was still at the head of Price’s Missouri column, soon encountered enemy soldiers. At 10 am, Federals had commenced nipping at the vanguard of his column with a scattering of skirmish fire. By that time, the Confederates had reached a forested ravine called Cross Timber Hollow, which marked the northern edge of Pea Ridge, a broad plateau covered with hardwoods and dense thickets of vines and brush. It was terrible ground for soldiers to fight on, since it did not afford much room to maneuver. At the edge of the ridge, Cross Timber Hollow was a low point just before the ground began ascending 300 feet to the top of the plateau. From the floor of the hollow, Van Dorn could see nothing of what lay beyond, and this blindness gave him pause. In truth, there was nothing more than a few companies of Federal cavalry at the front, but Van Dorn ordered Price to halt, deploy his entire force into a line of battle, and advance cautiously. It was a cumbersome maneuver to perform, and one that would take time. At one stroke, Van Dorn conceded an enormous advantage in time and terrain.

While Price’s deployment was taking place, McCulloch’s column of Texans, Louisianans, Arkansans, and Indians was shuffling down Ford Road to effect the junction that Van Dorn intended. Their advance was sluggish, as the men were weak with hunger and exhaustion, and the cavalry and artillery horses were jaded and no less famished than the men. McCulloch appeared to have lost some of his customary confidence, remarking cryptically to a group of Louisiana soldiers, “I tell you, men, the army that is defeated in this fight will get a hell of a whipping!”

McCulloch’s Column Meets Osterhaus’ Lines

McCulloch’s column reached a point a little over two miles from Cross Timber Hollow. As they marched, the men listened intently to the growing sounds of musketry rolling from the east, where Price’s men were skirmishing. All at once, however, their attention was fully occupied with matters closer at hand when hostile artillery fire erupted directly to the south. Osterhaus had arrived per Curtis’s instructions, and he sized up the situation immediately.

Realizing that McCulloch’s force represented a grave threat to the Federal rear, Osterhaus determined to launch a preemptive strike to keep the Rebels busy until he could report to headquarters and obtain reinforcements. Not waiting for his infantry to catch up, Osterhaus deployed three cannons and about 500 cavalry in the corner of a snowy wheat field, and ordered them to open fire. The resultant surprise was complete, as solid shot blasted the approaching Confederate columns. McCulloch was astounded, but recovered his composure quickly and ordered a massed cavalry charge against the thin Union line.

Thousands of mounted Texans and Arkansans wheeled their tired horses and spurred across the wheat field, screaming out Rebel yells and brandishing sabers, hatchets, knives, and shotguns. Firepower usually negated the shock value of massed cavalry, but this time the attackers had the advantage of overwhelming numbers, and they closed on the Federals almost immediately and commenced slashing and firing in a whirling storm. One of the Union defenders recalled, “In every direction I could see my comrades falling. Men and horses ran in collision crushing each other to the ground. Dismounted troopers ran in every direction.”

Osterhaus’s defense collapsed quickly, his cavalry breaking pell-mell for the rear. All three guns were lost. In a small accompanying action a short distance to the west, two companies of Union cavalry had the misfortune to blunder into Pike’s Indians. After a short victorious fight, the Indians went wild, dancing about the fallen Federals, scalping (so it was reputed) the dead and murdering a number of the wounded. That was the extent of the Indian participation in the battle—Pike was unable to get them back into line.

The ill-fated Union stand had bought Osterhaus the time to deploy his infantry, which he positioned along the southern rim just to the south beyond a belt of trees. This line too was thin, and Osterhaus penned a hasty note to Curtis requesting reinforcement, then opened with his remaining cannons.

For McCulloch, the appearance of the new force was a further vexation, and he determined that he could not continue his march to join Van Dorn while leaving Federals waiting compactly in his rear. He would have to smash them. To do so, McCulloch ordered up his weary infantry, instructed his cavalry to reform, and began sending out orders to coordinate a fresh attack. At this point, he made the serious oversight of neglecting to send word to Van Dorn of what had happened. This omission left Van Dorn with the inaccurate impression that the two wings of his army were still on schedule for an imminent junction at Elkhorn Tavern.

Two Generals Killed

Not satisfied that everything was in order, McCulloch rode up to his skirmish line for a last-minute reconnaissance in person. Nearing the belt of trees between the fields, he was suddenly met with a burst of musketry from Osterhaus’s skirmishers. One of the bullets pierced his heart, killing him instantly. The general’s staff was horrified, worrying that news of their beloved chief’s death would demoralize the soldiers. “We must not let the men know that General McCulloch is killed,” one officer declared, and the information was withheld from everyone except the next in command, McCulloch’s cavalry commander, Brig. Gen. James McIntosh.

McIntosh was an impetuous character in his own right, and he had no sooner assumed command than he ordered a piecemeal resumption of the attack. Making matters worse, he opted to lead the advance from the front, riding exuberantly along with the lead regiment. There, in the midst of the same belt of trees where McCulloch had fallen, McIntosh was killed almost immediately by Osterhaus’s skirmishers. The Confederate attack ground to a halt and confusion reigned. Most of the colonels were completely in the dark about who was in command; McIntosh’s instructions had been uncertain at best. With no direction from above, the various officers decided to cancel the forward movement and await orders—orders that would never come.

In the meantime, four regiments of Arkansas and Louisiana infantry did attack, striking southward pursuant to orders McCulloch had given just before he died. This action was wholly unsupported by the rest of the force at hand, and Osterhaus managed to repulse it with the help of 1,400 new troops that Curtis had sent him in response to his earlier request.

That ended the fighting on Osterhaus’s front, although he kept his men alertly in position throughout the day, watching the thousands of milling Confederate soldiers for any sign of belligerence. None was forthcoming. The various colonels kept sending couriers back and forth looking for McCulloch and McIntosh, and McCulloch’s staff never shared the critical information that the general was dead. The day passed agonizingly slowly, as the southern soldiers waited in the ranks, “in the most perplexed condition and mental anguish.” Finally, news of McCulloch’s and McIntosh’s deaths got out in the late afternoon. Even then, no one assumed command assertively, and regiments drifted rearward, some retreating back the way they had come, others moving to join Van Dorn. Many men simply fell out and collapsed into sleep. Van Dorn, too, remained in the dark about what was happening with McCulloch’s command. Still bottled up in Cross Timber Hollow, he was overseeing the final stages of Price’s deployment when hostile artillery fire broke from the ridge to the front.

Carr had arrived at Elkhorn Tavern with his brigade. As with Osterhaus to the west, Carr immediately surmised that the Confederate force in his front was considerably larger than his own command. (In fact, Price’s column was down to about 5,000 exhausted men after subtractions due to straggling, but Carr had only 1,400 troops of his own with which to meet them.) After dispatching a courier to Curtis with the now-familiar request for reinforcements, Carr settled on a spoiling attack to discombobulate the Confederates, and he proceeded north in person to lead a battery into position to start the action.

This was the artillery fire that confronted Van Dorn, and Price’s Missourians immediately ducked for cover as shrieking shots exploded overhead and pelted them with bark and leaves. In short order, Van Dorn summoned a battery to reply, and Price’s men hurried forward two more on their own initiative. There was a clear path to a reasonable incline in the terrain at the edge of the hollow, and the Missouri gunners were able to deploy their pieces to good effect, blasting the Federals with a blistering barrage of metal. The duel was uneven at the beginning—14 Confederate guns against four Federal pieces.

Carr’s gunners were pounded; limber chests exploded with great eruptions of fire and smoke, and Carr sustained a minor injury. The lopsided duel would probably have been more destructive but for the massive quantities of smoke the guns put up, which hovered densely in the hollow, making accurate fire all but impossible. To support the guns, Carr ordered forward his infantry, and the men shuffled about a third of the way down the uneven, icy slope and opened fire before ducking to the ground. It was a clever tactic, for Price assumed that he was about to be struck by an assault and concentrated on defending himself instead of marshalling his strength for a renewed attack that might have enabled him to break free of the hollow. Reinforcing Price’s passivity was Van Dorn’s steady optimism that McCulloch would arrive shortly to strike the Federals in flank and clear the ridge.

The battle raged monotonously. One participant remembered, “The incessant crash of musketry and roar of artillery, amid curtains of rising smoke, appeared both to sight and sound as if two wrathful clouds had descended to the earth, rushing together in hideous battle with all their lightning and thunder.” Curtis finally arrived at the front, having been drawn northward by the steady roar of gunfire. It had been a taxing morning for him. Curtis located Carr and rode up to confer with him, braving the crash of Confederate shrapnel. After a short conference, Curtis turned around to return to headquarters, having assured Carr that another brigade would soon be coming up to help him hold his position. On the way back, Curtis passed by the army’s trains where they were stationed in a field just south of Elkhorn Tavern. Curtis immediately ordered the trains moved to a safe location. It was a difficult maneuver for the teamsters to effect, but they did it well, providing a little breathing room for Carr in case he found it necessary to fall back.

At 12:30 pm, the first reinforcements arrived for Carr in the form of a brigade of 850 men. Carr immediately swapped out the beat-up artillery battery in his front line for a fresh one, and he ordered the new infantry to deploy and attack the enemy. This they did twice, and both times were repulsed. Price’s men were armed mostly with shotguns and outmoded smoothbores, but the smoke on the field was so dense that the Federals approached within 100 yards, and at that distance, the weight of numbers told. Carr was forced again to reassume a defensive posture, and the battle settled into a stalemate.

Van Dorn Assaults Pea Ridge

At 2 pm, Van Dorn finally learned by messenger that McCulloch was not coming to the rescue, information that trigged a change in tactics. Van Dorn immediately set about preparing for a frontal assault up the face of Pea Ridge. Realigning the weary Missouri soldiers took time, however, and in the midst of the movement the Confederate commander received a report that there was a clear path up the ridge to the east around the Federal right wing. Taking advantage of the opportunity, Van Dorn modified his plan and ordered Price to take a portion of his command out of line and up the ridge to strike the Federals in flank. If the two attacks could be coordinated, they would pin Carr in position and roll up his line, clearing the ridge entirely.

The wait for Price’s men to move into position was agonizingly long; the Confederate soldiers were reaching the limits of their physical endurance. Slumped on the cold, rugged ground, many fell asleep in spite of the continuing crackle of gunfire. Price, whose wounded arm was tied up in a sling, finally moved into position on the ridge with a detachment of 2,000 men and 11 guns. From there, he opened a brisk bombardment on Carr’s right wing. Unfortunately for him, Carr was not surprised, and in fact had prepared for just such an eventuality by refusing his right flank.

Carr had sensed that the long lull in the fighting corresponded to a Confederate buildup, and although he had only about 2,200 men in line to face Van Dorn’s command of 5,000, he was well placed to meet them, especially along his refused right flank, which enjoyed the cover of a breastwork of fence rails and logs. Price attempted to soften the Union position with a sustained artillery barrage, but the fire was largely ineffectual, and the subsequent assault was a bloody disaster. “We were met by a most terrific and deadly volley of musketry,” remembered one participant. The Missourians quickly returned to their jump-off point. Undaunted, Price opened with his artillery to try again.

In the meantime, Van Dorn had heard Price’s attack and ordered in the rest of the infantry straight up the face of the ridge. The terrain was not suited to linear battle, and the men, some of whom had to be awakened to participate, were hardly in condition for a vigorous assault. The result was a stumbling confusion of overlapping lines, with the men slipping and tangling their way through snags and brush. Carr’s men heard the approaching enemy soldiers crunching leaves before they could see them through the smoke. All at once the ridge erupted in musketry as the two sides came to grips with each other at less than 100 yards. The firing “was extremely heavy,” one officer recalled. The Confederate assault spent its forward momentum almost immediately, and the fighting settled into another stationary battle of attrition.

Somewhere in the midst of the chaos, Van Dorn finally received confirmation that McCulloch was dead and that his command was effectively without leadership. Van Dorn was too engaged in the fighting to respond actively to the disheartening news. He simply sent a quixotic order addressed to the ranking colonel to “hold his position at all hazards.”

By now, the weight of numbers was beginning to tell on Van Dorn’s front. His right overlapped Carr’s left, and as the Federal soldiers fell backward, the Confederates came whooping on. The advance was chaotic and disjointed, but it was enough, and Carr determined grimly to order a retreat. Price meanwhile had repeated his futile frontal assault on the Union breastwork before resorting to a more cautious attempt to turn the position. Carr’s men held on doggedly. Many who were too badly wounded to leave the field stayed at their places, sitting on the ground reloading and firing.

The Confederates swarmed over the top of the ridge and captured several cannons, but their movement quickly lost all remaining semblance of cohesion. Men fell out by the hundreds to search Elkhorn Tavern and the bodies of the fallen Federals for any scrap of food they could find. Those who did press on found out unhappily that Carr was still dangerous and resourceful, even in retreat. He had located another strong position some 600 yards to the rear along a fence on the south side of a cornfield. There he rallied his men and commenced punishing the exhausted Confederates, who flung themselves raggedly at his new line.

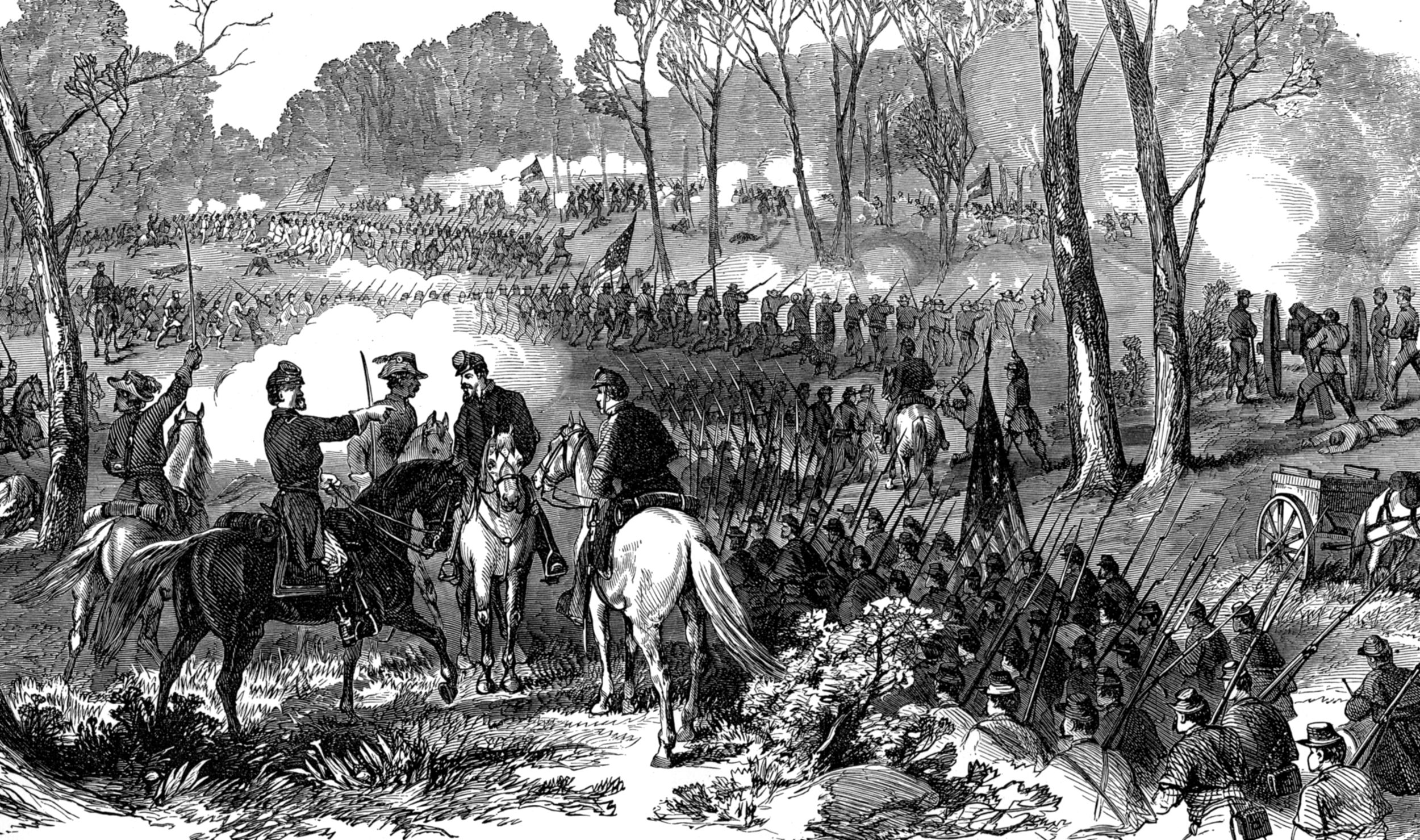

Counterattack by Curtis

In a climactic flourish, Curtis arrived on the dusky field in person at the head of his last division, which he had pulled from the entrenchments along Little Sugar Creek to rescue the beleaguered Carr. The force Curtis brought with him was small—only about 500 men—but its arrival had an electric effect on Carr’s division. Curtis ordered an immediate counterattack, and when Carr’s brigade commanders complained that they were out of ammunition, he told them to charge with bayonets. This they did. “Such a yell as they crossed that field with, you never heard,” one colonel recalled. “It was unearthly, and scared the rebels so bad they never stopped to fire at us or to let us reach them.”

The reversal was complete, but it was night now, and Curtis realized that he would have to finish the job in the morning. With this in mind, he pulled back the men into a compact line and ordered Sigel to bring up the forces that had been engaging McCulloch’s command, thereby effecting a concentration of the entire army. Curtis retired for the night in good spirits, confident of success the next day.

Across the field, the Confederate soldiers of Price’s command also passed the evening in an upbeat state. They suffered from lack of food and warmth, but most believed that they had won the day. Little was done to ready them for the next day’s fighting. Van Dorn did not concern himself with dressing ranks or realigning units. He did send orders to one of McCulloch’s colonels to bring that wing to Elkhorn Tavern. McCulloch’s men were still far away, however, and after making another terrible night march they arrived at dawn, staggering with fatigue and half-dead with cold and hunger.

Van Dorn arose feeling refreshed on March 8, having finally recovered from his illness. Hastily he reorganized his line, bringing up some of McCulloch’s haggard men. Then he opened the action with a strangely weak infantry probe against the cornfield where Price’s attack had petered out the previous night. Curtis was unimpressed. Leaving two of his divisions in position south of the cornfield, he ordered Sigel to swing his command around to the left and open the day’s attack with a preliminary artillery bombardment. Sigel complied immediately, and the result was the most intense, sustained bombardment to date on the American continent. It lasted over two hours and was brutally effective. “It was a continual thunder,” one man recalled. “A fellow might have believed that the day of judgment had come.”

Cowed by the thunderous artillery fire, Confederate soldiers hugged the ground while Van Dorn struggled to bring up his own batteries to reply, only to learn that his ammunition trains had gone missing in the night. The trains had followed the army on the march around the enemy’s Little Sugar Creek entrenchments, but Van Dorn had not kept track of their movements or thought to send orders to ensure that they followed closely. The result was that they were still far to the rear, some five to six hours away, and the Confederate soldiers and cannoneers on the scene were out of ammunition.

Impetuous as he was, Van Dorn realized that the game was up, and he ordered a peremptory retreat. As the Confederates began pulling out, Curtis launched a massive infantry attack with his whole force. They went in “with banners streaming, with drums beating and every man and officer yelling at the top of his lungs.” Some Confederate regiments did their best to resist the Union tide, but many were already retreating. Van Dorn was at the head of the withdrawal, and he left the field while a substantial portion of his army was still engaged. He did not even bother to ensure that all units got the order to retreat, which meant that many men were abandoned to their own devices. They scattered as they saw fit, fading into the countryside.

As it became clear that the Confederates were in retreat, Curtis rode his lines exuberantly, shouting: “Victory! Victory!” He was especially proud of the final push of his infantry. As he wrote later, “A charge like that last closing scene has never been made on this continent. It was the most terribly magnificent sight that can be imagined.” In the glow of success, Curtis momentarily lost track of Sigel, and the German general added a rather eccentric epilogue to the battle. Having convinced himself that the Federal attack was a desperate attempt to break free for a retreat instead of the final victorious jab at a defeated foe, he gathered his two divisions and broke across Cross Timber Hollow in a farcical lunge for the rear. It took Curtis a full day to catch up with him.

In the meantime, broken and demoralized, the surviving Confederates staggered across northern Arkansas in search of food. They pillaged farms, slaughtering and eating animals raw. “I was so hungry I even picked up turnip peelings out of the mud and ate them,” one Missouri soldier recalled. Eventually, Van Dorn managed to lead them south to a supply depot, where they slowly recovered. Once safely settled in, Van Dorn began blaming everything and everyone for the reversal. He refused to call it a defeat, insisting, “I was not defeated, but only foiled in my intentions.”

Regardless of such claims, the disastrous impact of Pea Ridge on Confederate fortunes was immense. Van Dorn lost some 2,000 men in the battle and an untold number of deserters and casualties due to illness and exhaustion, while he inflicted only 1,384 casualties on Curtis’s Army of the Southwest. More important, Curtis succeeded in his objective of securing Missouri for the Union. St. Louis would never again be seriously threatened, and Missouri would serve as stable base for the 1862 river offensives in Tennessee, which proved to be a smashing success. The Union victory at Pea Ridge was a blow from which the Confederacy would never fully recover.

Great info