By Eric Niderost

Around 8 o’clock on the morning of June 17, 1876, Brig. Gen. George Crook ordered his troops to halt along the banks of Rosebud Creek. The long trek from Fort Fetterman to the Rosebud Valley had been particularly grueling and the men were obviously in need of a rest. Crook was certain that somewhere up ahead—perhaps as close as five miles—there was a hostile village of Sioux and Cheyenne under the charismatic warrior Crazy Horse. If this was true, the need for rest and recuperation was all the more imperative.

[text_ad]

The halt was more than just a welcome respite from a long journey; it also allowed the dangerously strung-out command to come closer together. The troops had been awakened at 3 am and were in the saddle by 6. General Crook led the way astride a big black horse, the men tortuously negotiating their way along the banks of the South Fork of the Rosebud. The ground was crooked as a corkscrew, the sinuous stream snaking past high bluffs that loomed on all sides. Sometimes the path widened into grassy meadows, but other times it was so hemmed in by bluffs the troops found themselves on the very edge of the Rosebud, its sluggish waters engorged by spring’s snow melt.

When the column reached the confluence of the South Fork with the larger North Fork of the Rosebud, it turned eastward, still hugging the banks. A bivouac was established along a bottomland just west of a great bend where the Rosebud turned sharply north on its way to the Yellowstone River.

While their comrades in the rear struggled to catch up, lucky soldiers in the center and van could take their ease. Horses and mules were unsaddled, fires started, and green coffee beans were produced for roasting. The day was growing warm, with more than a hint of the torrid heat to come, but steaming hot cups of coffee were an eagerly awaited luxury in spite of rising temperatures. The Rosebud valley was particularly beautiful this languid summer morning, a country “green as an emerald” carpeted by verdant grass and flowering crabapple. Wild roses grew in abundance all along the creek, giving the Rosebud its distinctive name.

The flower-festooned valley seemed to cast a spell on the soldiers, and even their Crow and Shoshoni Indian allies seemed to enjoy a moment’s respite from the rigors of campaign. The troops were a grimy, dirty lot, and the heat had caused many to take off their dust-covered bluecoats to expose sweat-stained shirts of blue or gray flannel. Battered slouch hats perched on heads, and formerly clean-shaven soldiers sported a dark stubble of beard. Cheeks were distended by plugs of tobacco, chewed while waiting for coffee to be brewed. Soldiers slept, chatted with comrades, or watched friendly horse races between some Shoshoni and Crow.

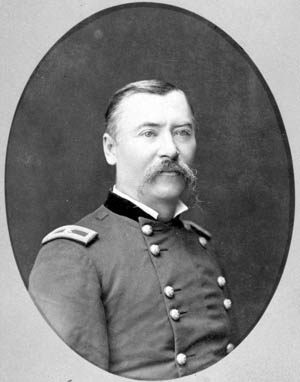

General Crook decided to wile away the time by playing cards with his aides. The general was known to Indians as “Three Stars,” presumably because they had seen him in full dress uniform, a shiny brigadier star perched on each shoulder and one fastened on his hat. If the Indians had seen Crook in full uniform they were lucky indeed, because the general’s affable eccentricity rarely allowed such a gaudy display. Dressed in battered, nondescript civilian garb, a “shockingly bad” hat pulled over his close-cropped head, Crook was a startling contrast to such flamboyant, colorful officers as George Armstrong Custer.

Crook was modest, taciturn, and usually kept his own counsel. On campaign he parted his long blond beard into braids, a style more reminiscent of Blackbeard the pirate than a U.S. Army general. His most recent Indian fighting experience was with the Apache in the Southwest, and he seemed to have little notion of the superb fighting capabilities of the Plains Indians. Captain Anson Mills, commander of the first battalion, 3rd Cavalry, later remarked that, “from conversations with him I felt he did not realize the prowess of the Sioux.”

Captain Alexander Sutorius, Company E, 3rd Cavalry, was enjoying a smoke with Lieutenant Adolfus von Leuttwitz, who had just transferred to his command. Sutorius was a Swiss, von Luettwitz a German—two Europeans in the middle of an American wilderness. Their reverie was rudely interrupted by the distant reports of rifle shots coming from behind the northern bluffs. “They are shooting buffalo over there,” Sutorius opined to Frank Finerty, a journalist from the Chicago Times who was accompanying the expedition. Crook had sent Crow and Shoshoni scouts out the night before; maybe they were hunting to supplement the expedition’s larder.

Suddenly a score or more scouts appeared on the northern bluffs, then galloped wildly into camp on lathered horses shouting “Lakota! Lakota! Heap Sioux! Heap Sioux!” Accounts differ slightly, but one version claims a hunchback Shoshoni named “Humpy” was the first bearer of evil tidings, followed by Crow scouts. One of the Crows was badly wounded and bleeding profusely, mute but eloquent testimony that the Sioux and their Cheyenne allies were indeed on the move.

The news the hostiles were about to attack shattered the camp’s tranquility. All was action as McClellan saddles were strapped to horses’ backs, fires kicked out, and weapons checked. To the untrained eye the bivouac was utter chaos, with men swinging into saddles, officers barking orders, horses prancing, and mules braying loudly. But the pandemonium was more apparent than real, because underneath the storm and fury each man knew his assigned place. The Battle of the Rosebud was about to begin.

The coming contest was part of what historians call the Great Sioux War of 1876, a conflict that had its roots in the dispute over the Black Hills of South Dakota. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 established a Great Sioux Reservation in what later became the state of South Dakota west of the Missouri River. The Teton Sioux, in their own language “Lakota,” were actually a collection of seven tribes. Known as the Seven Sacred Campfires, the member tribes included the Oglala, Brule, Miniconjou, Two Kettle, Sans Arc, Hunkpapa, and Sihasapa.

The chiefs who “touched the pen” and signed the 1868 treaty seemed reasonably satisfied with the terms, and indeed they had wrung some concessions from the wasichus, the white men. The hated Bozeman Trail to the Montana goldfields was abandoned, as were the “soldier forts” along the route. The government also promised clothing and rations for 30 years, always an enticing prospect. But historians still debate if the Indians really knew what they were signing. The 1868 treaty was nothing less than a profound, even radical, change in Indian lifestyle. Schools were to be established to “civilize” the Native American, changing him from nomadic hunter to subsistence farmer.

Not every Sioux supported the 1868 treaty, and many traditionals preferred the old ways. The Hunkpapa Tatanka Iyotaka, known to the whites as Sitting Bull, was one of those who rejected the white man’s foreign ways. He was a Wichasha Wakan,, a holy man who could see visions and possessed great spiritual power. About a year before the 1868 treaty he berated some Assiniboine Indians, declaring, “You are fools to make yourselves slaves to a piece of fat bacon, some hard tack, and a little sugar and coffee.”

Another traditional Sioux was the Oglala warrior Taschunka Witko, “His Horse Is Crazy” or Crazy Horse. Remote, laconic, seldom speaking in council, he was a man apart. The Oglalas called him “our strange man,” an epithet that was one of affection as well as awe. Above all, Crazy Horse was a great warrior, a man whose courage, resourcefulness, and innate leadership abilities blossomed in battle.

Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse became prominent leaders of the nontreaty or nonreservation bands, holdouts who preferred to roam free rather than be confined to a reservation. The 1868 treaty seemed to tacitly acknowledge that traditionals rejected reservation life by establishing an “unceded territory” sometimes called the “Powder River annex.” This unceded territory lay just to the west of the Great Sioux Reservation, extending to the summit of the Bighorn Mountains.

Purposely vague to win greater acceptance by Indians, cloaked in legalese and Victorian rhetoric, the unceded territory clause provided a haven for traditionals. In the rough and remote Powder River region the traditionals could hunt buffalo and pursue traditional folkways, free of the burdensome restraints of reservation life. By the same token reservation Indians could “take up the white man’s road” without interference from conservative traditionals. Most white authorities considered the arrangement a temporary one, because the buffalo were disappearing at a fairly rapid rate. Once there were no buffalo to hunt in the Powder River unceded territory, even traditionals would be compelled to return to the reservation.

But trouble began in the 1870s, when rumors of gold in the Black Hills began to circulate. In 1874 a well-mounted expedition under Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer explored the hills and confirmed the existence of the precious metal. Rumor was now fact, triggering a gold rush of major proportions. The Black Hills were part of the Great Sioux Reservation, and as such whites were absolutely forbidden to trespass. Thousands of prospectors stampeded into the region anyway, and the U.S. Army kept them out with varying success and very little enthusiasm.

Washington began to talk about “extinguishing Indian title” to the Black Hills—a euphemism for total white takeover. The Administration of President Ulysses S. Grant wanted peace, but political pressures became too great to ignore. Some 15,000 prospectors were already swarming through the Black Hills, a gold-hungry horde that the army seemed unable or unwilling to completely bar. The Grant Administration made some attempts to buy the Hills, efforts that were in the main rejected by the Sioux.

On November 3, 1875, President Grant met secretly with Indian officials and army generals to determine the future course of government policy. It was decided the army would stop trying to hold back the tide, and “cease its fruitless efforts to ban civilians from the Hills.” The army had been a deterrent, albeit a feeble one, to white encroachments. Now the floodgates would be open, and the Black Hills taken over in fact if not in name.

But Grant and his advisers were well aware the Sioux would resist the takeover, especially the nontreaty bands now roaming the unceded territory. To draw the fangs of the Sioux nation and neutralize any possible resistance, the power of the nontreaty bands would have to be curbed. To this end an ultimatum was issued ordering all bands to “report to their agencies” by January 31, 1876. The ultimatum targeted the nontreaty bands, in essence ordering them to evacuate the unceded territory and come back to the reservation and white supervision.

It was well known that Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse were against any cession of Indian land to the rapacious whites, and they had to be brought to heel before any Black Hills takeover could succeed. “Le makoce mitawa kin he e!” Crazy Horse declared in his Oglala Lakota dialect, “This land is mine!” To Crazy Horse the land was his birthright and the birthright of every Lakota, and this was more than just a ringing phrase, but a watchword to live by.

It was well known that Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse were against any cession of Indian land to the rapacious whites, and they had to be brought to heel before any Black Hills takeover could succeed. “Le makoce mitawa kin he e!” Crazy Horse declared in his Oglala Lakota dialect, “This land is mine!” To Crazy Horse the land was his birthright and the birthright of every Lakota, and this was more than just a ringing phrase, but a watchword to live by.

Searching for a justification to clothe their naked aggression, the U.S. government pointed to Sioux raids that occurred along the Yellowstone River. These depredations were real but exaggerated, and some of the incidents had been directed against the Crow, the Sioux nation’s traditional enemies. In December 1875 runners were dispatched to the Indian winter camps in the unceded territory to inform them of the January 31 deadline. The date came and went and the bands still occupied the Powder River country. The nontreaty Sioux were busy hunting buffalo, and by the time the messengers reached them heavy snows made movement difficult if not impossible.

This is not to say the Indians had any intention of complying with government demands. The ultimatum was incomprehensible to Indian leaders, and besides, they had little notion of time as the white man measured it. The idea of a specific date labeled “January 31, 1876” was an alien concept. Since there was no sign of Indian compliance Secretary of War William Bellnap turned the matter over to Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan, commander of the Department of the Missouri. Sheridan was certain a winter campaign would be the most effective means of dealing with the “hostiles.” In winter, food was scarce, and Indians were largely confined to snow-bound villages. Immobilized by inclement weather, they were vulnerable to attack.

The planned offensive would consist of three columns, two from Brig. Gen. Alfred H. Terry’s Department of Dakota and one from Brig. Gen. George Crook’s Department of the Platte. But winter weather could immobilize soldiers as well as Indians, and General Terry’s preparations were delayed by deep snows and bitter cold. Heavy snows also made it more difficult for soldiers in scattered forts to concentrate in designated staging areas; in some cases troops had to march four hundred miles over icy trails to reach their destinations.

Back in his Chicago headquarters, “Little Phil” Sheridan chafed at the delays but accepted the inevitable. In an official report Sheridan noted Terry’s mounting difficulties, stating that “the snow was so deep” and so many cavalry troopers had been “badly frostbitten” it was “thought advisable to abandon the expedition until later in the season.”

Terry’s problems and temporary withdrawal left only Crook able to mount an offensive action. In March 1876 Crook departed Fort Fetterman in fine spirits, certain he and he alone could defeat the hostile bands. Crook subordinate Colonel Joseph Reynolds located an Indian village nestled in a valley on the Powder River. Reynolds attacked at once, and though he managed to occupy the village and destroy tipis and precious food and robes, the Indians rallied and turned the tables on the bluecoats. Reynold’s men were driven back and even the Indian pony herd was recaptured.

Crook, impatiently expecting a decisive victory, was angered and embarrassed by Reynold’s well-publicized failure. The colonel became a scapegoat for an abortive campaign and was later court-marshaled. In order to salvage something out of the fiasco it was claimed that Reynolds had destroyed Crazy Horse’s village. In reality, it had been a largely Cheyenne encampment under Cheyenne chiefs Old Bear, Little Wolf, and Two Moon.

General Crook was nothing if not a realist and withdrew his men into winter quarters, allowing them to rest and refit while they awaited the coming of spring and better weather. It would be two long months before Crook would take the field again. By early April the campaign against the Sioux began in earnest. There would be three converging columns, in theory at least acting in concert with one another. The Montana Column under Colonel John Gibbons left Fort Ellis and struck east, its ultimate destination a rendezvous with General Terry’s Dakota Column coming out of Fort Abraham Lincoln.

The Montana Column was the smallest of the three, some 450 men from the 2nd Cavalry and 7th Infantry, together with some 25 Crow scouts. Terry’s command numbered about 925 men, including 12 companies of the 7th Cavalry, three infantry companies, and about 25 Arikara scouts. Crook’s Wyoming Column was the largest of the trio, including 10 companies of the 3rd Cavalry, five companies of the 5th Cavalry, and two companies each from the 4th and 9th Infantries. One historian reckons Crook’s force at the start of the campaign at 47 officers and 1,002 men. In addition, a pack team of 81 men and 250 mules accompanied the expedition, as well as a mule-drawn wagon train of 116 men and 106 wagons.

Few whites had ever ventured into the unceded region, save for a few hearty scouts and hardbitten trappers. It was pure wilderness, boasting some of the most beautiful—and rugged—landscape on the North American continent. Snowcapped mountains spiked the sky, and wild, tumultuous rivers roared through rocky canyons and narrow gorges. The soldiers were supposed to locate and defeat an elusive enemy hiding somewhere within a hundred thousand square miles of wilderness.

Few whites had ever ventured into the unceded region, save for a few hearty scouts and hardbitten trappers. It was pure wilderness, boasting some of the most beautiful—and rugged—landscape on the North American continent. Snowcapped mountains spiked the sky, and wild, tumultuous rivers roared through rocky canyons and narrow gorges. The soldiers were supposed to locate and defeat an elusive enemy hiding somewhere within a hundred thousand square miles of wilderness.

Around noon on May 29, 1876 the Wyoming Column—officially designated the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition—finally departed Fort Fetterman on the North Platte River. The troops moved in a northwesterly direction, following the old Bozeman Trail for the first leg of the journey. Fort Fetterman had been considered a hardship post, even by the low standards of the frontier, and in due course it was abandoned altogether. The cavalry took the lead, their company guidon flags fluttering in the breeze, sunlight sparkling on their weapons. The infantry came next, the scissoring legs of the foot soldiers kicking up a choking plume of dust that rose into the sky. The pack train of heavily laden mules marched single file to the right of the main column, and canvas-topped wagons rattled along behind the infantry, axles groaning in protest.

Altogether the column stretched for four miles, but there were few civilians to admire the martial spectacle. The troops did get a send-off from the denizens of the Hog Ranch, a saloon and brothel located about a mile from the post. The prostitutes waved handkerchiefs in fluttery salute to their departing customers. No doubt the parting was bittersweet, because the “soiled doves’” income was going to be sharply reduced by the bluecoat exodus.

For two or three days the going was fairly easy, with wood and water in abundance. On June 1 slate-gray clouds moved in, dumping snow and sleet on the heads of the shivering soldiers. The breath of men and horses crystallized in the frigid air, producing great vents of steam as they exhaled. Soldiers huddled in their pale-blue overcoats, the more inexperienced no doubt marveling at weather that seemed more January than June.

The column trekked on, reaching the ruins of Fort Reno on June 2. Crook had expected Crow and Shoshoni scouts to rendezvous with him here, but they were nowhere to be seen. It was always Crook’s policy to “fight fire with fire” by using Indians who used the same warfare methods as hostiles. Once they agreed, the two tribes were willing enough—after all, the Sioux were their traditional enemy.

Crook dispatched his three guide/interpreters, Frank Grourard, Louis Richaud, and Baptiste “Big Bat” Gaunier, to try and find the Crow and Shoshoni. While the general fretted, an incident occurred that provided a light moment for the rank and file. One of the civilian teamsters was discovered to be a woman in disguise, a great embarrassment to the wagonmaster who hired her. It seems she was unmasked because she didn’t lash her mule team and was unable to swear properly. A teamster was expected to let loose with a stream of colorful profanities with every crack of the whip. The woman was none other than “Calamity Jane,” who later became celebrated as one of the “characters” of the Old West. Calamity was given something approximating female attire and later sent back.

The general pushed on, reaching the site of Fort Phil Kearney before turning northwest and leaving the Bozeman Trail. Crook had intended to follow Little Goose Creek to Big Goose Creek, but lacking guides—they were still out hunting the Crow and Shoshoni—the general took a wrong turn. The column mistakenly followed what turned out to be Prairie Dog Creek, only discovering the error when it flowed into the Tongue River. It was a grueling march, with winter-like weather replaced by a humid, sticky heat that Lieutenant John Bourke, one of Crook’s aides, describes as “sultry.” The ground was rough and steep, so Crook decided to stay put for the time being. A camp was established along the Tongue River.

On June 9 a band of Northern Cheyenne under Little Hawk galloped up atop some bluffs just north of the river, diving in cavalry pickets as they did so. The Cheyenne poured a heavy fire into Crook’s camp, a rain of bullets that peppered and shredded the soldiers’ tents. Luckily most of the tents were unoccupied, the troops being outside at mess. Surprised that their dinner included a leaden “dessert,” the troops dropped tin plates and grabbed weapons.

Captain Anson Mills took companies A, E, I, and M of his 3rd Cavalry and forded the Tongue in pursuit of the hostiles. Once across, the troopers dismounted to climb the bluffs. The Indians retreated to another bluff, then finally melted back into the landscape. The 2nd Cavalry had been skirmishing on the left, turning back a small party of Indians who had forded the river. A probing attack from the south was also successfully repulsed.

The skirmish added zest to the campaign, a seemingly good omen of things to come. Casualties had been light, with only two soldiers wounded. There was a funny postscript to the fight, because reports mentioned an Indian bullet had passed through the pipe of Captain Mill’s stove. When Eastern newspapers took up the story, mentioning the captain’s “stovepipe,” an editorial berated the officer for wearing a top hat on campaign!

Yet for all the bellicose high spirits and rollicking good fun, the skirmish was an odd foretaste of the Battle of the Rosebud, with Indians playing “hide and seek” up and down precipitous bluffs. Correspondent Finerty, the “Fighting Irish Pencil Pusher,” noted that time and again the Indians “shot a volley,” then “skedaddled to the bluff further back.” although the Cheyenne gave way to a determined charge, their retreats were cold calculation, not panic. As Finerty shrewdly observed, “To say the truth, they [the Indians] did not seem badly scared.”

Crook now moved the expedition westward, to the confluence of Little Goose Creek and Big Goose Creek, there to await his Indian allies. On June 14, the camp was galvanized by the sight of 176 Crow warriors under Old Crow, Medicine Crow, and Good Heart. The Crow made a favorable impression on the soldiers, resplendent in multicolored blankets, buckskin or cotton shirts, breechclouts, and moccasins. The Crows were well armed, .50-caliber carbines supplemented by tomahawks, knives, and lances.

Not long after, 86 Shoshoni arrived in camp, led by their renowned chief Washakie. The man was in his early 70s, but his legendary prowess in battle was undiminished by advancing years. His men were also a colorful lot, black hair adorned with feathers, and faces painted for war. It was said earlier that one of the Shoshoni was seen carrying a rod with two severed Sioux fingers dangling from it—digital equivalents of a scalp. Some civilian miners from Montana also joined the column.

Once his Indian allies arrived, Crook felt the campaign could begin in earnest. A flurry of orders came from his headquarters’ tent, directives designed to speed the search for the hostiles. Crook decided to abandon his logistical “tail” in the interest of greater mobility, so the wagons and most of the pack train would be left behind. The supply wagons were gathered on a small island in Goose Creek, and one hundred men—soldiers and civilians—detailed to guard them. Soldiers were ordered to carry only the bare necessities, and no one, from the highest officer to the lowest private, would be exempt from this command. Each man was to carry four days’ rations, which might include hardtack, coffee, sugar, and a generous chunk of elk meat. Tents were also considered useless impediments; from now on, their only roof would be the vault of the sky.

In an effort to boost mobility Crook decided the infantry should be mounted on mules. It was easier said than done, since most of the soldiers had never ridden before, and the draft mules had never had anything on their backs heavier than harnesses. The infantry, called “Walk a Heaps” by Indians, were given a crash course—almost literally—in equestrianship, the lessons conducted by some slightly embarrassed officers. The Goose Creek camp dissolved into noisy chaos as mules kicked, bucked, and brayed in protest, dumping their novice riders into the dirt. Cavalrymen enjoyed the “circus,” convulsed with laughter at the mules’ antics, but eventually the animals were broken to the saddle. The mounted infantry were no longer foot-sore, but would now discover aches in another part of their anatomy!

The march resumed early on June 16, the column proceeding in the general direction of the Yellowstone River. The country was verdant, speckled by wildflowers and sagebrush. Herds of shaggy buffalo grazed on the emerald-green grass. The command reached the headwaters of the Rosebud, where camp was pitched for the night. The mounted infantry rode into camp in fine style, but when Major Alex Chambers gave the command “Left front into line,” the animals complied with a series of loud brays. When his brother officers began to laugh at the absurd spectacle, Chambers lost all control. The humiliated major let loose with a stream of profane oaths, threw his sword to the ground, and stomped off in disgust.

Crook had hoped to surprise the hostile village, but his presence had already been detected. A Cheyenne hunting band composed of Little Hawk, Yellow Eagle, Crooked Nose, Little Shield, and White Bird had stumbled upon the bivouac. The Cheyenne could hardly believe their eyes; it seemed “as if the whole earth were black with soldiers.”

They raced back to the Sioux-Cheyenne village that had been recently established on a creek that flowed into the Little Bighorn River. The hunting party wolf-howled as they approached the camp, the mournful wails an established cry of alarm. The news spread like wildfire, and though the chiefs counseled caution—“Young men leave the soldiers alone unless they attack us”—their advice fell on deaf ears. Lakota men were itching for a fight, but women struck conical tipis and prepared to flee, since it was well known bluecoats liked to attack villages. The words “Siye! Siye! Akicita wasichu! Inyanka!” (Watch out! Watch out! White soldiers are coming! Run! Run!) echoed through the village.

Warriors literally stripped for battle, most wearing breechcloths and moccasins, and proceeded to daub their faces and bodies with paint. Horses’ tails were bound up, and equine bodies were also painted to complement their riders’ adornments. Braves dashed out of the village like a swarm of angry hornets, different groups taking different routes to the soldier camp. There were around a thousand warriors all told, every man ready to do battle with the bluecoats.

The Battle of the Rosebud began when the hostiles clashed with the government Indian scouts about eight to ten miles from Crook’s bivouac. The scouts had little option but to gallop back and spread the alarm, the Sioux hard on their heels. It had been their frantic cries of “Lakota! Lakota!” that first gave Crook an inkling he had a major battle on his hands.

Crook’s bivouac was located in a kind of natural amphitheater surrounded by a series of bluffs that paralleled the Rosebud. The bluffs to the north are some two hundred to six hundred yards from the Creek; behind them a huge ridge forms a rocky spine that stretches for five miles before ending in a high promontory now called Andrew’s Point. Another ridge, or series of rippling ridges, juts in from the southeast, joining the first in a kind of acute angle. Between the two ridges was a dry watercourse called Kollmar Creek.

Crook’s bivouac was located in a kind of natural amphitheater surrounded by a series of bluffs that paralleled the Rosebud. The bluffs to the north are some two hundred to six hundred yards from the Creek; behind them a huge ridge forms a rocky spine that stretches for five miles before ending in a high promontory now called Andrew’s Point. Another ridge, or series of rippling ridges, juts in from the southeast, joining the first in a kind of acute angle. Between the two ridges was a dry watercourse called Kollmar Creek.

When the attack began Crook’s command was on both sides of Rosebud Creek. Captain Henry Noyes’ battalion of five companies of the 2nd Cavalry was located on the north side of the stream, with Captain Frederick Van Vliet’s battalion of two companies of the 3rd Cavalry following behind. Long-suffering Major Alex Chambers’ “mule brigade” came next, five companies of mounted infantry, then the Montana miners. The Crow and Shoshoni allies under Captain George M. Randall brought up the rear, completing the forces on the north bank.

Captain Anson Mills’ battalion of four companies of the 3rd Cavalry was just across the Rosebud near the southern bank, accompanied by Captain Guy Henry’s four companies, also from the 3rd Cavalry. Counting all the troops, the Indian allies, and the civilian miners and packers, it is estimated Crook had 1,325 men.

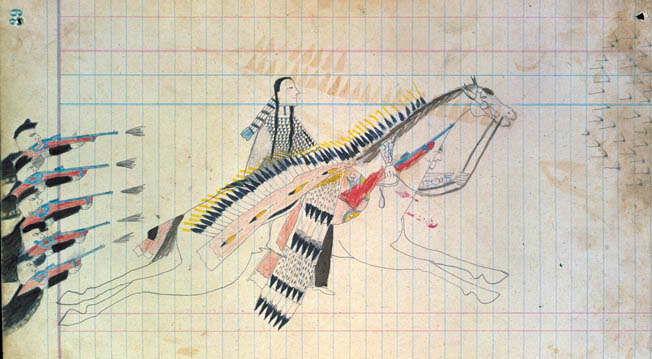

Hundreds of Sioux and Cheyenne warriors appeared on the northern ridges, magnificent warriors in full regalia. Almost as if to taunt their unprepared enemies the braves—according to one witness—“dashed here, there, everywhere; up and down in ceaseless activity; gaudy decorations, waving plumes, and glittering arms, form a panorama of barbaric splendor.” Sioux rifles sent a scattering of shots into the soldier camp, a prelude to an all-out charge. The warriors surged forward, a human avalanche that seemed to gain momentum as it spilled down the slopes. The camp was unprepared for the onslaught, but just when things seemed their blackest, Chief of Scouts Captain Randall came bounding forward with the Crow and Shoshoni allies. Indian fought Indian for a good 20 minutes, the Shoshoni and Crow buying precious time for Crook to organize an adequate defense.

Individual warriors on both sides engaged in “bravery runs,” near-suicidal attempts to prove courage by deliberately drawing fire. Warriors were so intoxicated by the sheer joy of battle they scarcely felt wounds. Crow brave Bull Snake lay propped up against a tree with a bullet-shattered thigh, yet seemed oblivious to the pain as he “yelled like a madman” to encourage his comrades.

When the fight started Crook mounted his horse and rode to a hill to get a clearer picture of the overall situation. His absence was ill timed, because rapid Indian movements demanded immediate attention. Tactical command fell to Major Andrew Evans, 3rd Cavalry, who hastily issued a flurry of orders to deal with the developing crisis. Evans immediately dispatched Captain Van Vliet’s Company C and G, 3rd Cavalry, to take and hold the southern bluffs as a kind of defensive rearguard. Evans’ foresight proved invaluable, because Van Vliet’s men had scarcely occupied the southern bluffs before they repulsed a group of hostiles riding in from the east.

Evans now turned his attention to other pressing matters. Company G and H of the 9th Infantry were ordered to advance and hold the low bluffs to the north, with four dismounted companies of the 2nd cavalry in close support. Captain Thomas B. Dewee’s A Company, 2nd Cavalry, was given the onerous task of horse holders for three other companies now going into action.

To the west, Company C of the 9th Infantry and Company D and F of the 4th Infantry were sent forward in a skirmish line, eventually reaching the plateau where the Crows and Shoshonis were engaged in their holding action. Crow warrior Plenty Coups later recalled the fierce fighting, saying,“The enemy were like lice on a robe, and hot for battle.” Dust swirled, guns flashed, and Indian war cries echoed over the bluffs. The Crows and Shoshonis managed to smash the Sioux line, but the two broken halves tried to gallop around the government Indians to get at the foot-slogging, sweating soldiers coming up just behind. One party of Sioux rode east down a ravine, hoping to surprise the soldiers and steal their cavalry mounts in the valley below.

Alert to the danger, soldiers from the 9th Infantry and 2nd Cavalry prepared an ambush for the unsuspecting foe. At about 150 yards the troops unleashed a volley, a deadly gray rain of .45-caliber slugs that tore gaping wounds and tumbled warriors into the bloodstained earth. Their attack blunted, the Sioux split yet again into two separate streams, one of which managed to gain a northern ridge just in time to confront a cavalry charge led by Captain Mills.

Crazy Horse was present in the battle, conspicuous by his very simplicity of dress and manner. He wore a skin cape, but no war bonnet. The great Lakota warrior is sometimes credited as being the “commander” of the Sioux host at the Rosebud, a notion that displays little understanding of Plains Indian ways. Crazy Horse might suggest tactics, and warriors might listen, but Lakota leaders led by example alone.

Just prior to his departure to the observation knoll Crook sent Lieutenant Henry Lemly with an order to Captain Mills to “clear the center bluffs” just north of his position. Mills had already crossed the Rosebud, and once established on the north bank was in a good position to fulfill the general’s directive.

Mills, a distinguished-looking man whose trimmed mustache and goatee gave him the look of a cavalier, barked the command “Front into line” to his battalion. Each trooper had held his “trapdoor” .45-caliber Springfield carbine at the ready—sabers were rarely used on the frontier. Then Mills rose in his stirrups and shouted “Charge,” the order amplified by the brassy notes of a trumpeter’s bugle. His battalion, consisting of companies A, E, I, and M, bounded forward like a torrent. “We went in like a storm,” recalled one participant, and the crest of the bluffs were soon taken.

The captain’s charge was so rapid there was scarcely any time to use carbines, so troopers drew their single-action Colt revolvers and squeezed off a few rounds. The Sioux replied in kind, long plumes of smoke and flame jetting from their guns as they darted from place to place on swift ponies. Some Indian bullets must have found their mark, since horses tumbled and troopers spilled headlong into the dirt, but the others pressed on. The troopers reached the summit with a loud cheer, the Indians melting way before such a determined assault.

Indian warriors then taunted advancing troopers, slapping their buttocks in mockery. Other braves repeatedly exposed themselves to bluecoat fire. The Cheyenne Comes in Sight’s horse was stopped in its tracks by a .45-caliber slug, but the warrior landed on his feet and began to run. A hail of bullets dogged his every step, but just when all seemed lost his sister Buffalo Calf Road Woman rode up to save him. Comes in Sight leaped onto her horse and the pair made good their escape. Because of this incident the Cheyenne called the Battle of the Rosebud “Where the Girl Saved her Brother.”

Captain Mills found himself on a rocky ridge, which came under fire from another ridge about a half-mile distant. Dismounting the battalion, Mills went forward in a line of skirmishers. Even during the height of the fighting Mills couldn’t help admiring the superb equestrianship of the hostiles, men whom he considered “the best cavalry soldiers on earth.” Warriors galloped about, now advancing, now retreating, coming “in flocks or herds like buffalo.” The Indians were colorful; the Cheyenne Black Sun, for example, painted his entire body yellow, his loins wrapped in a blanket and the stuffed skin of a weasel on his head.

The Battle of the Rosebud was a complicated affair, made more confusing by the rugged terrain and the hostiles’ will-o’-the-wisp tactics. Some of its details are obscure, or at least subject to differing interpretation, to this very day.

Now dismounted, Mills’ troopers advanced and took the second line of bluffs just as the 2nd Cavalry took the ridge on the left. Crook came back from the observation hill and ordered Mills to take a rise [later to be known as Crook’s Hill]. Three companies under Lt. Col. William Royall would provide close support. Once again Mills led an adrenaline-pumping, pulse-quickening charge that was successful. Once again the Indians gave way, retreating to a conical mound some 1,200 yards from Crook’s Hill. During Mills’ charge, Lt. Col. Royall noticed gaudily painted warriors along a row of ridges about one mile southwest, across Kollmar Creek. Royall detached his three companies and went after this new threat, driving the hostiles in a northwesterly direction.

The colonel drew rein and halted on a ridge about a mile from Crook’s Hill, but Captain William Andrews led a platoon from his own Company I, 3rd Cavalry, to a high, wind-swept promontory—“Andrew’s Point”—that afforded a good view of the surrounding countryside. Lieutenant James Foster led another platoon just to the west and south of Andrews.

Andrews and Foster’s positions proved untenable, so they were recalled. Both men managed to reach Royall safely, but the colonel himself was “out on a limb” a mile from Crook and increasingly bothered by Indian enfilading fire. Crook’s command now had three far-flung components: Royall to the west, Crook in the center, and Van Vliet still holding the rear on the southern bluffs. It was time for consolidation, so Crook ordered Royall to extend his right and link up with the general’s main command.

Crook was dangerously strung out, in part because the bluecoats were reacting to Indian movements rather than following a rational plan of their own. The Sioux and Cheyenne had been moving “sideways” across Crook’s front, a crablike shuffle that moved ever westward. At the same time the Indians were playing a deadly game of “leapfrog” with the troops, retreating from hill to hill with the bluecoats in hot pursuit. The various components of Crook’s command—particularly Royall’s—were in danger of being isolated and destroyed in detail.

By about 10:30 am the Indians seemed to be concentrating on Royall, almost instinctively going for the jugular of his isolated command. The colonel was soon surrounded on three sides and subjected to an enfilading fire from the recently evacuated Andrew’s Point. Carbines pumped smoke and flame with clockwork regularity, the troopers flipping open the trapdoor of their weapons, then pushing the ejector to fling spent cartridges into the dust. Ordered by Crook to rejoin the main command, Royall was forced to conduct a fighting retreat.

The battle became a confusing jumble of events. The Cheyenne Wooden Leg recalled that “until the sun went far toward the west there were charges back and forth. Our Indians fought and ran away. The soldiers and their scouts did the same. Sometimes we chased them, sometimes they chased us.”

Amid the noise, smoke, and blood of battle some incidents stood out in sharp relief. During Royall’s retreat Sergeant David Marshal and a handful of men from Company F, 3rd Cavalry, were completely cut off and trapped by scores of hostiles. The troopers sold their lives dearly; though they were hot from constant use, carbine barrels pumped a steady stream of lead at the onrushing warriors. When the last round was fired the troopers fought on with clubbed carbines until only two were left, Private Phineas Towne and Private Richard Bennett. Bennett was cut to pieces, but Towne survived when other cavalry appeared and chased away his attackers.

Captain Guy Henry, 3rd Cavalry, was struck in the face by a bullet, the projectile drilling through his left cheek and exiting his right. Reeling in pain, temporarily blinded (he lost the use of one eye permanently), Henry’s mustache, face, and uniform were drenched in blood. Henry tumbled to the ground, the Sioux rushing forward to finish him off. The wounded officer was saved by a Crow countercharge, which rode though the Sioux warriors and forced them to turn tail.

Crook wanted Royall to join him because he was still under the impression—a false one—that the village was nearby. The beleaguered colonel managed to link up with Crook, thanks partly to a timely Crow and Shoshoni charge. Mills had been cautiously probing on the left, still hoping to take the hostile village, but when Crook saw how dangerous the situation had become he recalled him.

The Sioux and Cheyenne broke off the action around 2:30 pm. After six grueling hours, the Battle of the Rosebud petered out, sputtering like a gutted candle. The Indians did not have the white concept of total victory or defeat; they “were tired and hungry, so they went home.” Due in part to the confused nature of the fighting, casualty figures are disputed. Officially Crook lost nine men killed and 21 wounded, a suspiciously low figure that seems “doctored” for home consumption. Another report concedes 10 dead, four mortally wounded, and 43 less seriously hurt. One of the civilian scouts estimated 28 soldiers killed and 56 wounded, a figure than may be closer to the truth. The Crow claimed one killed and 10 wounded, the Shoshoni one killed.

Sioux and Cheyenne casualties are even harder to assess. Crazy Horse supposedly admitted to 36 killed and 63 wounded, a not-incredible figure given the battle’s length and hard-fought qualities. The Battle of the Rosebud was one of the great Indian fights of the 19th century, but it has been obscured by the events that occurred along the Little Bighorn River a week later. The sheer magnitude of the Custer disaster, coupled with his flamboyant and controversial personality, has relegated the Rosebud to a nearly forgotten footnote in history.

The Battle of the Rosebud was a prelude to disaster, yet there is reason to believe that Crook’s fight had a direct bearing on the Little Bighorn. If Crook had won on the Rosebud, perhaps Custer and his immediate command would not have been wiped out. Despite face-saving reports to the contrary, General George Crook was defeated at the Rosebud both strategically and tactically. In fact, the sheer shock of the unaccustomed reverse seems to have thrown Crook into an uncharacteristic lethargy, an over-caution that was also to have an impact on future events.

Crook maintained that he then needed reinforcements, even though his command was large and far from shattered. He made no attempt to immediately renew the advance—in fact, he didn’t even send a message to Terry to at least let the latter know what he was up against or that he had fought a battle. Instead, Crook and his men enjoyed a languid “vacation,” hunting and fishing, a holiday that extended into the period Custer searched out these same hostiles (who had now moved their village) and proceeded to be wiped out, some 60 miles to the north.

George Crook was one of the finest Indian fighting officers the army ever produced, but during the Great Sioux War he seems to have experienced a temporary—and to Custer, fatal—lapse in his powers.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments