By Arnold Blumberg

Its name has become synonymous with intrigue, conspiracy, betrayal, and assassination. It was responsible for the overthrow, abandonment, or murder of 15 out of the first 48 emperors who governed Rome between 27 bc and ad 305. Its deterioration into a ruthless mercenary force is its most enduring legacy. Yet the original purpose of the Praetorian Guard was far from the brutal history it eventually left behind.

Created by the first emperor of Rome, Augustus, the Guard was designed to protect the monarch and the royal family, thus extending their reign and keeping the army, Senate, and Roman mob in line. The only armed troops allowed to be quartered south of the Rubicon River, Italy’s northern boundary, the Guard massed at their citadel, the Castra Praetoria, a potent political as well as military force. Their cooperation would assure stability in the Empire by shielding the emperor from harm, thus making his will supreme and his actions final.

The origins of the Praetorian Guard were rooted in a practice common to the armies formed by Republican Rome. Beginning in the third century bc, Roman military commanders created a small body of soldiers to act as their bodyguards. Such units first appeared in the armies raised by the Scipio family in 275 bc. (The Scipio clan would continue to have an important influence on Roman military defense policy and expansion through the first century bc). During the siege of Numantia, which ended in 133 bc, Scipio Aemilianus formed a bodyguard of 500 men, about the size of a normal Roman cohort. This was the largest personal guard ever created for the protection of a Roman general up to that time, a fact that was widely commented upon by contemporary observers.

A Roman general (known as an imperator) would raise a volunteer unit, usually from ordinary legionaries, or in some cases from auxiliary troops recruited from areas outside Rome, which would be specially designated to protect him and his staff while on campaign. These elite units were called praetorian guards (in Latin: praetoriani), taking their name from the general’s headquarters tent (praetoria) found in every army camp.

Most Roman generals of the Republic and early Principate periods were not just military leaders, but provincial governors as well. This combined position elevated them to the status of proconsul, or propraetor. Whatever his actual title, the proconsul would come from the Roman aristocracy following a career involving a succession of roles, some civilian in nature, others connected with the military. As a provincial governor, he combined both civil and military responsibilities, administering the province or leading an army, whatever the situation required. To accomplish his duties, particularly in running the day-to-day operations of an army, the proconsul needed the assistance of an able staff.

The leader’s staff (cohor praetorian) was composed of two elements. One directed the administration of the army—the quartermasters, engineers, and volunteer aides—while the other directed the fighting men. The latter group constituted a commander’s bodyguard. It also acted as his ready reserve during battle, an elite contingent of picked men always at the leader’s immediate disposal. Members of this complement included friends and relatives of the general, as well as particularly competent tribunes and centurions who knew how to handle themselves and their troops in a fight.

Often an army commander created a single praetorian cohort combining both administrative and combat functions. This was the case with Julius Caesar, who, during his campaign against the German leader Ariovistus in 58 bc at the start of the Gallic Wars mounted a unit of 900 foot soldiers of his 10th Legion to act as his bodyguard for the duration of the campaign. Lucius Sergius Catiline, during his revolt against the Consul Marcus Cicero in 63-62 bc, had 2,000 veteran centurions and legionaries called the Sullani who acted as his bodyguard and principal strike force. In contrast, while governor of Cilicia in Asia Minor in 52 bc, Marcus Cicero formed two distinct praetorian cohorts: one designed as a combat unit, the other a purely administrative entity.

None of the great political-generals of the Late Republic—Sulla, Marius, Pompey, Catiline, or Caesar—employed praetorian cohorts. Caesar wrote that, while fighting in Spain in 49 bc against Pompey’s ally, Marcus Petreius, he had “a praetorian cohort of shield men.” But because these shield men were Spanish, not Roman, it was not considered a true praetorian cohort.

The units used as Praetorian Guards were raised at the start of each campaign. The general would select the most experienced soldiers from his legions. They would be volunteers who were of good health, highly decorated, and usually veterans (evocati). Many were men who had finished the standard term of service (in the case of an ordinary legionary or centurion that meant 25 years) but chose to reenlist. As praetorians, they would receive certain benefits not accorded regular troops. Length of duty with the praetorian cohort was 16 years; pay was 50 percent greater than for nonpraetorians. They were also exempted from mundane camp duties and received a greater share of booty. In return for the benefits and rewards, the praetorians were expected to be more than mere parade- ground soldiers or a protective screen for the army commander. Armed with the same weapons as other legionaries—pelium, gladius, short dagger, shield, leather body armor, and helmet—they were expected to function as the army’s backbone and serve as its shock troops when called upon to be so.

Praetorian cohorts were never a standardized or formally recognized formation in Roman armies during the murderous civil wars that racked the Republic during its last 100 years. Cornelius Sulla conducted his wars against the Marians in 88 and 83-82 bc without the mention of a bodyguard taking part in any critical battles, although one was certainly present. His campaign in Greece (87-86 bc) against Mithridates of Pontus likewise had no specialized corps of troops personally attached to him. The reign of terror Sulla visited upon his enemies after his final defeat of the Marian party in 82 bc proved a different matter. Under the leadership of Lucius S. Catiline, many of the former opposition were declared traitors to the state and executed. As a trusted member of Sulla’s staff and one of the officers of his bodyguard, Catiline became Sulla’s chief executioner, using soldiers of the praetorian cohort to hunt down and kill those fatally proscribed.

Sulla’s equivalent of the Praetorian Guard were the Sullani, a group of perhaps 3,000 veteran legionaries and centurions picked for their blind obedience and ruthlessness. They fought for Sulla in all his campaigns but were never acknowledged as a separate military unit. Catiline became their leader and used them in punitive expeditions to help consolidate Sulla’s power during the years 91 though 80 bc. After Sulla died in 78 bc, Catiline’s ambition led him to run for a consulship in 63 bc. This scion of the patrician Sergii clan was beaten by the commoner Marcus T. Cicero. Outraged by his defeat, Catiline raised an army in revolt against the Senate. His best troops were the old Sullani who flocked to his cause under the command of a former centurion, Gaius Manlius.

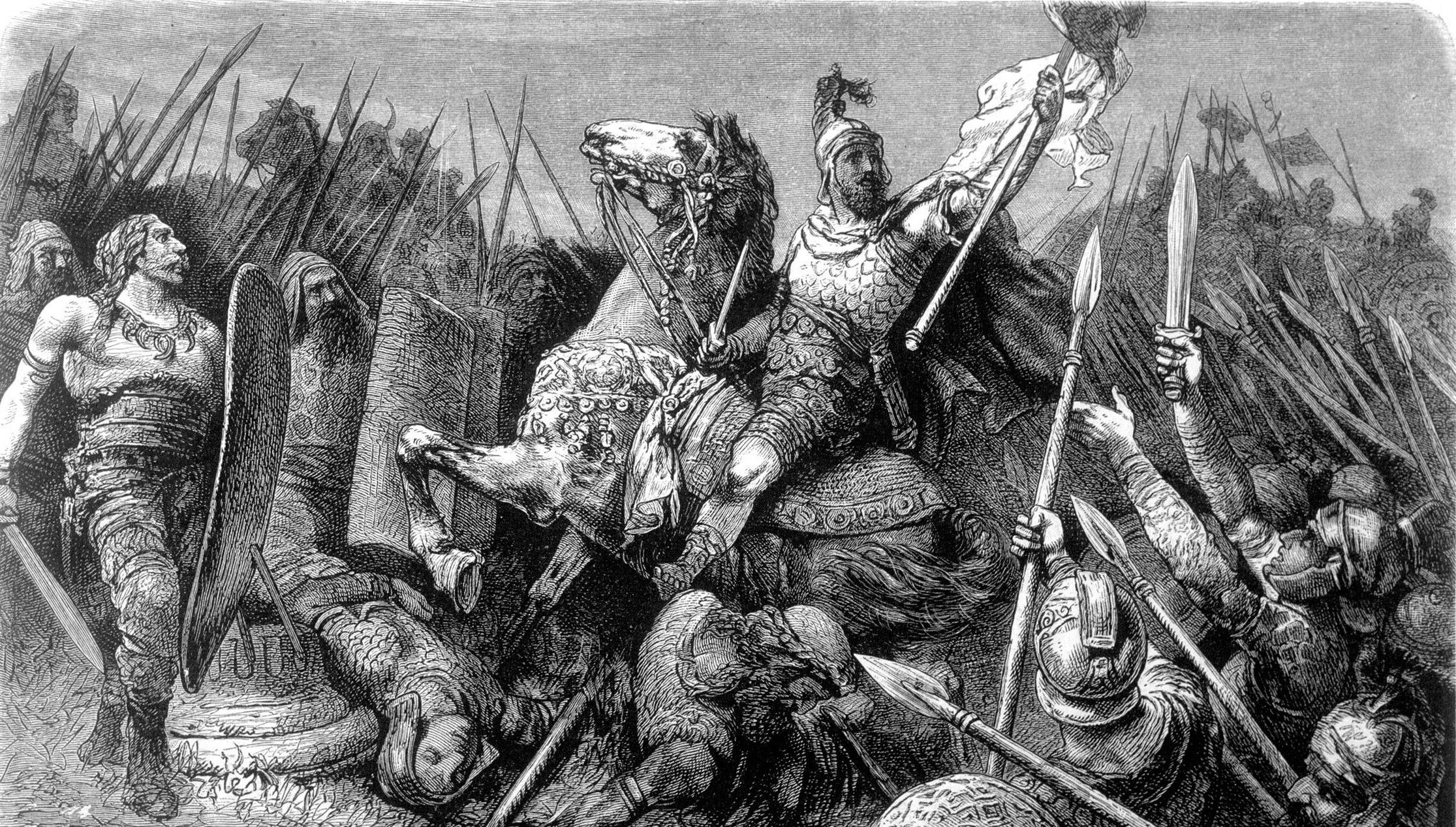

In January 62 bc, a powerful senatorial army under Marcus Petreius met Catiline’s numerically weaker force near the town of Pistoria. Forming in a valley that could not be outflanked by his enemy, Catiline’s men engaged Petreius main force. According to Gaius Sallust, legionary commander under Caesar, the Sullani made up the rebel army’s center and began to slowly push their enemy back. Fearing defeat, Petreius sent in his reserves, made up of his Praetorian Guard, which he led himself. Petreius was able to rout Catiline’s army—except for the Sullani, who stood and fought until they all had fallen. Catiline, seeing his army collapse, charged into the midst of Petreius’s soldiers and died fighting.

Soon after Caesar’s murder in March 44 bc, Caesar’s chief lieutenant, Mark Antony, and Octavian, Caesar’s adopted son and heir, prepared to battle their fallen leader’s murderers. They raised thousands of men from Caesar’s former legions, including a 6,000-man force Antony dubbed his “bodyguard” but never officially listed as one of the regular cohorts raised for the army. In October 44 bc, he recruited a single cohort that he formally designated as his Praetorian Guard. These troops came from legions recently transferred to Italy from Macedonia. Soon they were joined by another sent by his ally, Marcus Lepidus.

The alliance between Antony and Octavian took a heated turn when their newly fashioned armies fought each other in April 43 bc on the marsh and scrubland at Forum Gallorum. It was a grim and bloody fight, with the two praetorian cohorts under Antony coming face-to-face with the single praetorian unit mustered into service by Octavian. The Roman historian Arrian reports that the opposing praetorians, being all veterans, “raised no war cry, since they could not expect to terrify each other, nor did they utter a sound during the fighting they met together in close order, and since neither could dislodge the other they locked together with their swords as if in a wrestling match. No blow missed its mark. There were wounds and slaughter but no cries, only groans. They needed neither admonition nor encouragement, since experience made each man his own general.”

After a prolonged contest, Octavian’s men were forced to retreat to their camp when Antony’s cavalry threatened to surround them. Octavian’s praetorians were utterly destroyed. After a further battle between them at Mutina, Antony and Octavian finally got around to dealing with the men who assassinated Caesar. Antony defeated the “liberators” (as the killers of Caesar called themselves) at the Battle of Philippi, in Greece, in 42 bc. Of the 8,000 legionaries who reenlisted with Antony’s army, 4,000 were enrolled in his praetorian cohorts, which suffered heavily at Philippi. The balance of the other 4,000 enlistees entered the ranks of Octavian’s praetorian cohorts. These helped make up for the loss of 2,000 praetorians raised by Octavian after Forum Gallorum who were lost at sea when their transports were attacked and sunk in the Adriatic Sea by a fleet commanded by Brutus.

Octavian’s newly organized praetorian cohorts proved their worth in containing a breakout by enemy forces at the siege of Perusia in 41-40 bc. Antony was not so fortunate in his 36 BC attempt to invade Parthia. Motivated by a desire to avenge the Roman defeat at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 bc and gain new glory for himself and his men, Antony launched a new campaign that proved to be a disaster. His invading army included at least three praetorian cohorts, many of whom would die of starvation, exposure, or enemy arrows. Antony lost 22,000 men on the Armenian highlands during his subsequent retreat from Parthia, without bringing his enemy to a single conclusive battle.

In early 32 bc, Octavian seized control of Rome and declared war on Antony’s ally, Cleopatra, queen of Egypt. Coming to his lover’s aid, Antony fielded an army of 23 legions, four of which would man his 500-ship war fleet. Antony had at least two praetorian cohorts. There was also a cohors speculatorum, a praetorian-like unit that provided him with close protection and also functioned as spies and executioners.

Confronting Antony were Octavian’s 24 legions and a fleet of 400 warships, the latter manned by five praetorian cohorts serving as marines. Commanding his fleet was Marcus Vispanius Agrippa. Unable to bring Octavian to battle on land in northern Greece as he wished, Antony accepted battle on the water. The result was his defeat in the Battle of Actium (September 2, 31 bc). Eleven months later, Octavian landed at Alexandria, Egypt, to find that Antony had committed suicide and his army was ready and willing to transfer their loyalties to him. Culling the best men from Antony’s former army, the new ruler of the Roman world established nine cohorts of Praetorian Guards. In 27 bc, upon Octavian’s assumption of the purple under the name of Augustus, the praetorian cohorts were formally sworn in as the emperor’s Imperial Guard.

For the next three centuries the fortunes of the Praetorian Guard rose and fell with those of their masters. They assassinated several demonstrably evil emperors, including Caligula, Commodus, and Elagabalus, but they generally preferred to stay out of the limelight. At length, during the reign of the co-emperors Diocletian and Maximian (ad 286-305) the praetorian cohorts were dispersed around the empire and their manpower was drastically reduced. In response, the remaining guardsmen proclaimed their own candidate, Maxentius, emperor in ad 306 and fought to the death with him at the Battle of Milvian Bridge six years later. Maxentius’s opponent, and the ultimate victor in that contest, Constantine the Great, disbanded the surviving praetorians, sending them to the various corners of the realm. He also demolished the Castra Praetoria, thus forcefully underlining the end of the Praetorian Guard as a formal military entity.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments