By Darrell W. Coulter

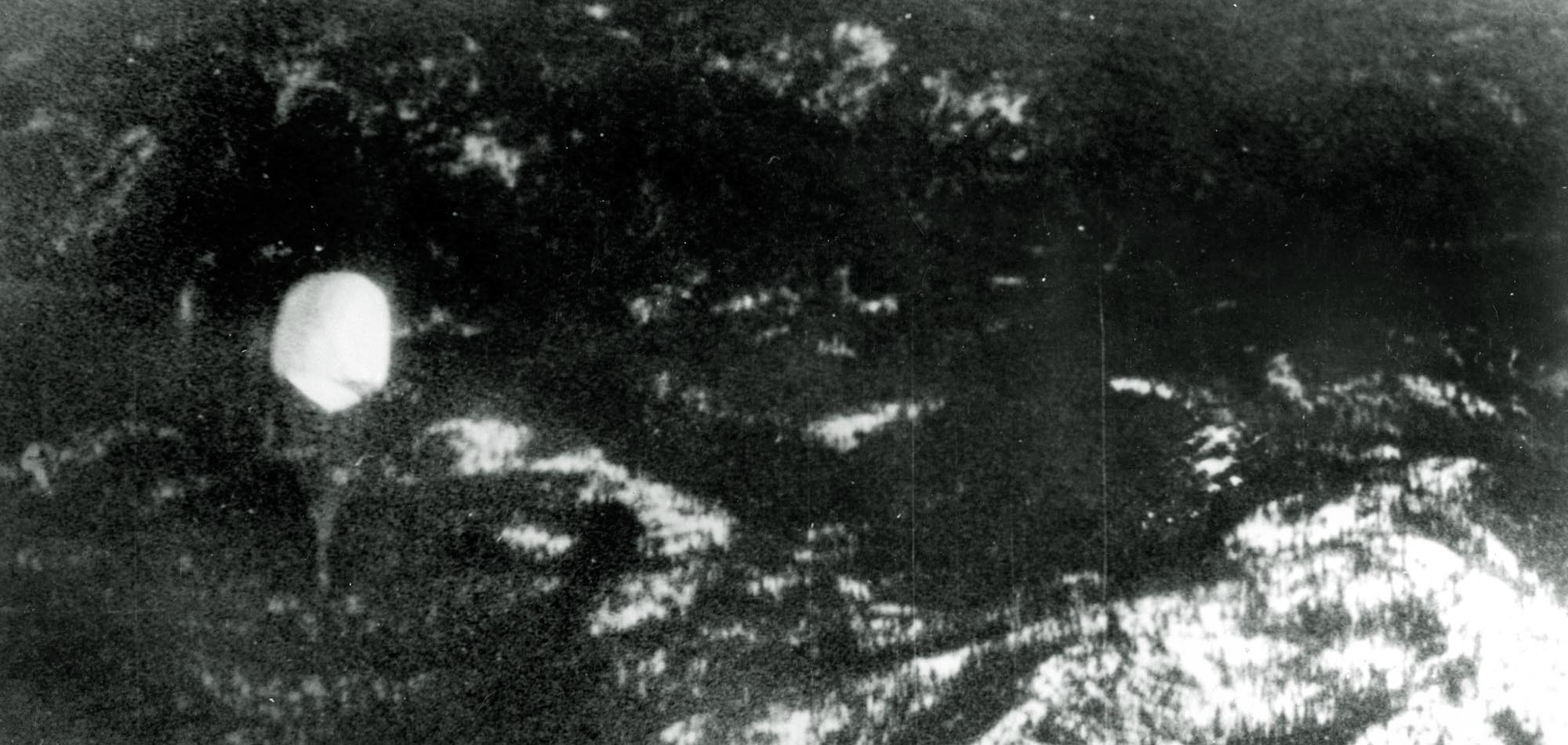

It crossed silently on a chilly winter evening over the southern Oregon coast, descending slowly, its ballast spent. The Japanese bomb-laden paper balloon collapsed into the Gearhart Mountain forest near the line separating Lake and Klamath Counties in south-central Oregon. The undercarriage of the 70-foot balloon slammed into the earth, its impact muffled by several inches of snow, which prevented a 33-pound high-explosive antipersonnel bomb from exploding.

This was only one of an estimated 6,000 balloon bombs, codenamed Fugo, launched by the Japanese Army from the main island of Honshu between November 1944 and April 1945. Flowing along the jet stream, their cargo of incendiary and high-explosive bombs reached North America in less than a week.

Finding the Pacific Stream

The origin of the Japanese balloon bombs dated back to the occupation of Manchuria in the early 1930s. The Japanese hoped to harass the Soviets across the Amur River, the border between Japanese-occupied Manchuria and Soviet Siberia, by dropping propaganda leaflets from those balloons. Though the plan was never carried out, Japanese military scientists gained valuable information about the complexity of balloon flights over considerable distances. The idea of eventually using balloons to transport special troops or deliver bombs held promise for the Japanese military.

In 1940, the Japanese purchased daily weather maps from the United States Weather Bureau after discovering the existence of an air current moving west to east from Japan to the North American continent at a high altitude. Traveling at over 30,000 feet, it was possible for a balloon launched from Japan to cross the Pacific Ocean in an optimum timeframe of three days. It was not until late in the war, with the beginning of long-distance American bombing of the Japanese home islands, that the United States and its allies learned about the existence and importance of the jet stream.

During the summer of 1942, some consideration was given to a new use of the balloon project on the island of Guadalcanal. The Japanese proposed to attach grenades to long lengths of piano wire that were held aloft by balloons in hopes of snaring U.S. Marine fighter planes as they took off from captured airfields on the island.

How to Make a Fire Balloon?

As the fortunes of the Japanese forces on the island turned against them in September 1942, the idea was redirected into a plan for transcontinental balloon bombing. The Japanese saw two distinct possibilities for success. By attacking the richly forested areas of the U.S. Pacific Northwest with incendiary devices, they hoped to tie up military and civilian resources as well as cost the Allies millions of dollars in damage. Of even greater importance, the Japanese believed that the panic created would have a great psychological impact on the citizens of the West Coast.

As the fortunes of the Japanese forces on the island turned against them in September 1942, the idea was redirected into a plan for transcontinental balloon bombing. The Japanese saw two distinct possibilities for success. By attacking the richly forested areas of the U.S. Pacific Northwest with incendiary devices, they hoped to tie up military and civilian resources as well as cost the Allies millions of dollars in damage. Of even greater importance, the Japanese believed that the panic created would have a great psychological impact on the citizens of the West Coast.

The technical problems with Project Fugo, which literally translates as “balloon bomb,” were enormous but not insurmountable. Two rival military groups were charged with overcoming these challenges to create a reliable bomb delivery system. The first, headed by Maj. Gen. Suiki Kusaba, commander of the First Division of the Ninth Army Technical Research Laboratory, was composed of Japanese Army personnel. Kusaba’s group concentrated its efforts on controlling the balloons in flight, arming them, and launching them successfully. Though inter-service rivalry existed, the Army’s work complemented the efforts of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Under the direction of naval ordnance engineer Lt. Cmdr. Kiyoshi Tanaka, the Navy had been developing a reliable radio transmitter that could survive high altitudes over long distances. The goal was to supply atmospheric information and determine the effects of air pressure on the interior and exterior walls of the balloon. Tanaka’s experiments with radiosondes using balloons 20 feet in diameter were successful. Those balloons could rise to an altitude of 25,000 feet and travel 435 miles. Tanaka hoped to overcome this limited range by using submarines off the American coast as launch platforms.

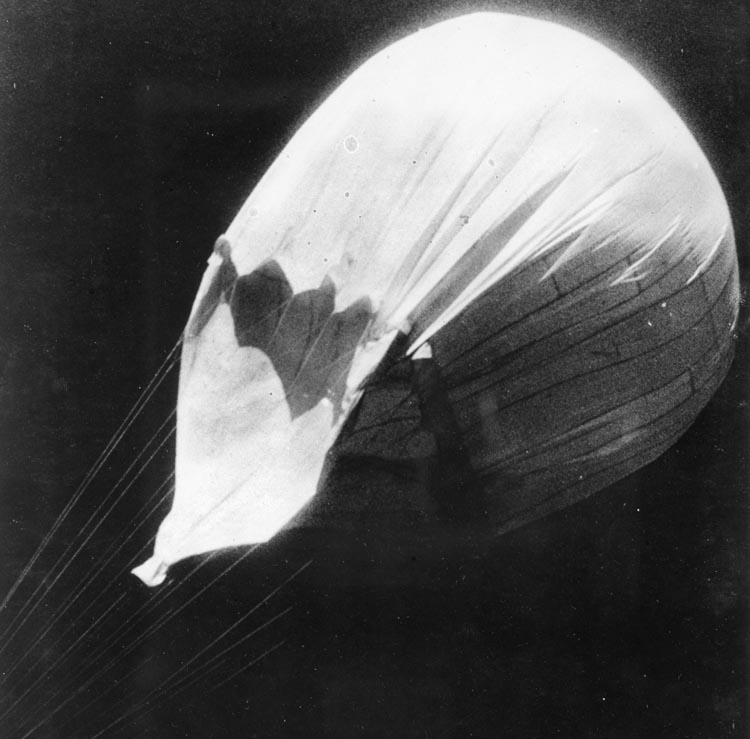

By this stage of the war, the Imperial naval forces were stretched to their limits. The valuable submarines that were left could not be spared for Tanaka’s experiments. However, he was not dissuaded. By early 1944, he had developed a 29.5-foot balloon composed of rubbercovered silk panels. This fabric made the balloon durable, leak proof, and most importantly, flexible enough to withstand expansion and contraction due to changes in air pressure.

The balloon also had to endure extreme temperature fluctuations during flight over a period of several days at maximum altitudes. The panels handled pressure extremely well. However, the glue that held the rubberized panels together did not. This failure resulted in a tendency for the balloons to rupture at the seams or explode under extreme pressure.

The Army’s balloon had been developed separately. It was made of more economical paper and was eventually chosen for the continuation of the project. Only 34 of Tanaka’s rubber balloons were approved for launch, none of which contained explosives. Tanaka’s balloons carried only radiosondes to collect data and sand for ballast.

The Army’s paper balloon was lighter and easier to launch, could carry a larger payload, was less expensive, and was slightly larger at 32.8 feet in diameter. This paper balloon was held together by komyyaku-nori, an adhesive gum made from the arum root. It was made waterproof through the use of a lacquer-like substance made from the fermented juice of green persimmons. This unlikely delivery system was chosen to carry the cargo of destruction to America.

The typical paper balloon consisted of a balloon envelope with a flexible belt uniting the upper and lower spheres. The bottom of the bag usually contained a pressure-operated valve for controlling the inflation of the balloon in response to outside temperature and pressure. The ballast and armaments hung from a gondola or ballast ring suspended from a single cable. The cable, comprised of two 50-foot shroud lines, ran through grommets set into the hemisphere-connecting belt.

The ballast ring was set to release ballast sand bags and four small incendiary bombs weighing just over 11 pounds each, through a series of blow-plugs. A platform was placed in the center of the ring. On top of the platform rested a wet-plate battery, a picric acid block for self-destruct, several electrical contact points for the auto-firing system, and four aneroid barometers that would start the firing mechanism once it fell below a preset altitude.

The ballast ring was set to release ballast sand bags and four small incendiary bombs weighing just over 11 pounds each, through a series of blow-plugs. A platform was placed in the center of the ring. On top of the platform rested a wet-plate battery, a picric acid block for self-destruct, several electrical contact points for the auto-firing system, and four aneroid barometers that would start the firing mechanism once it fell below a preset altitude.

Though the blow-plug mechanism system was designed to keep the balloons at a constant altitude, the extreme temperature fluctuations between night and day made that goal impossible. The balloons that reached the North American coast always crossed at varied altitudes. The last of the blow-plugs designed to go off were attached to long fuses leading back up the balloons’ envelopes, triggering self-destruction after the ballasts and bombs were dropped. This mechanism was designed to keep all intact balloons from being discovered.

In addition to the four small incendiary bombs, the Japanese included one 33-pound high-explosive antipersonnel bomb with an instantaneous fuse. This bomb was designed to spread shrapnel up to 300 feet away.

Ideally, once all of the sand ballasts had been exhausted the incendiary bombs would be released one by one as the balloon lost altitude. After the last incendiary bomb dropped, the larger antipersonnel bomb would be released. At that point, the picric acid block would explode, destroying the balloon’s undercarriage. This explosion would then light the last fuse, igniting the hydrogen gas used inside the shroud, thus destroying the balloon’s envelope and all remnants of its existence.

Transcontinental Balloon Bombing Begins

On November 3, 1944, the first of 6,000 bomb-laden balloons lifted from their moorings and headed toward North America. Though the weather at that time of year was not conducive to starting forest fires, the Japanese hoped that panic would be the measure of their success. Even as the first balloons lifted off, General Kusaba was experimenting with larger balloons for a planned summer offensive strike when the woods would be tinder dry. Though the estimates vary, records indicate that a minimum of 6,000 balloons were launched over the six-month period between November 1944 and April 1945.

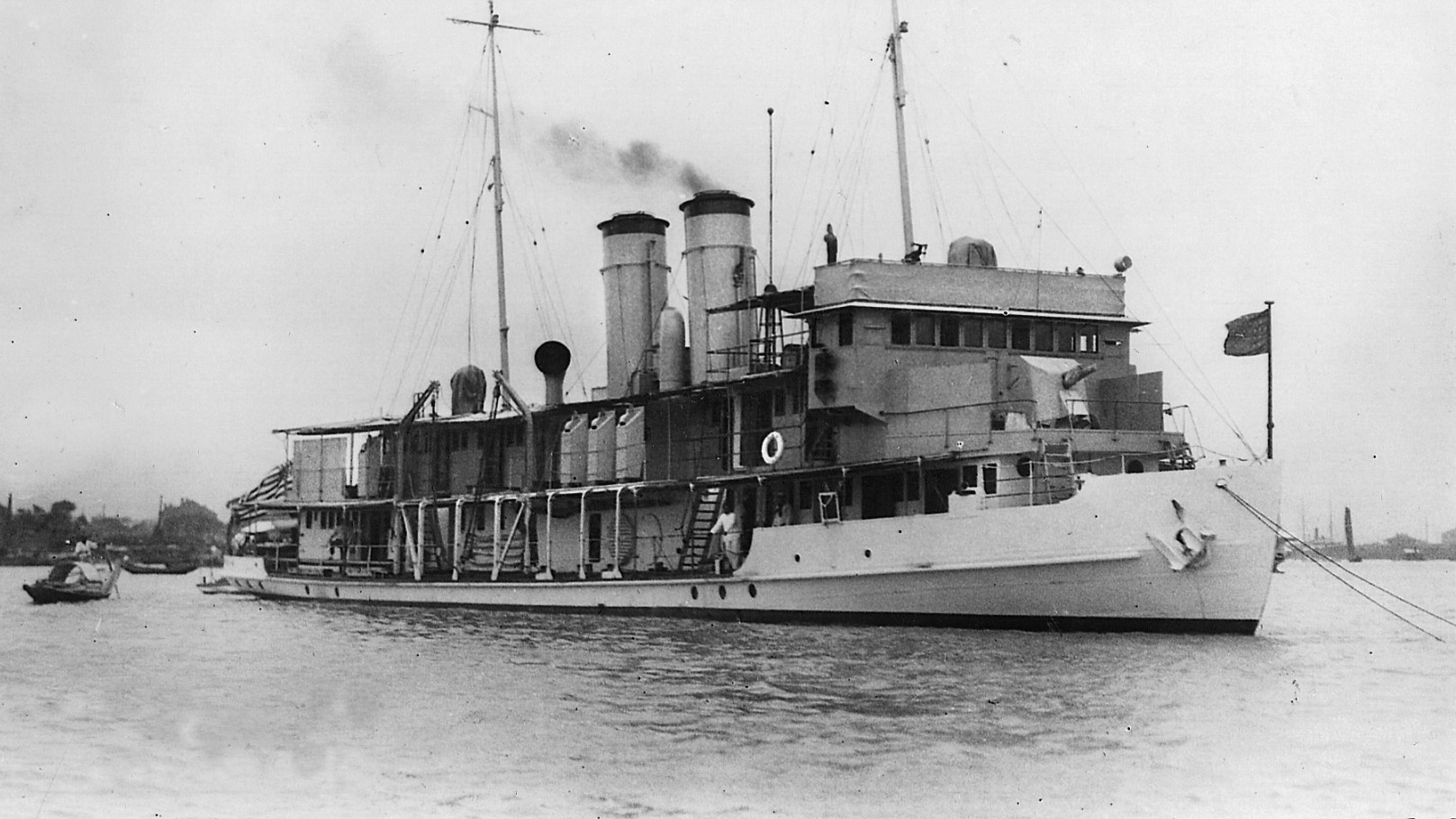

The first balloon was discovered on November 3, 1944, off the coast of San Pedro, California, by a U.S. Navy patrol craft. It was one of Tanaka’s rubberized silk models carrying a radio transmitter. The first recorded bombing from a balloon occurred on December 6, 1944, outside Thermopolis, Wyoming. The Independent Record, a weekly newspaper at Thermopolis, reported the incident. It was believed that the bomb was dropped from a plane. Witnesses reported seeing a parachute land with flares. The local authorities abandoned their search for the parachute, believing it to have been only a landing flare.

Less than a week later, a balloon with an unexploded bomb was discovered outside Libby, Montana. This one was reported in the December 14, 1944, issue of the Western News, a weekly newspaper in Libby. The story was picked up by both Time and Newsweek magazines for their New Year’s Day editions. The writers for both magazines were as puzzled by the purpose of the balloon as the people of Libby. In a follow-up story two weeks later, Newsweek, citing government sources, concluded that the reported balloons had a limited range of 400 miles and were probably launched from submarines.

On the evening of January 2, 1945, Mrs. Evelyn Cyr arrived home and witnessed an explosion in a field next to her house on Peach Street in Medford, Oregon. An investigation by military personnel from nearby Camp White revealed that the explosion was caused by a small incendiary bomb. This was one of the first recorded instances of balloon bombings in Oregon, the state in which the most incidents were recorded. The rest of the balloon and its deadly payload were not recovered in the Medford area.

American Response

Authorities were quick to act. A news blackout was issued, requesting the press not to print any news about the balloon attacks. Cooperation among military and civilian authorities was total. The military and several federal agencies, including the FBI, U.S. Forestry authorities, and the Department of Agriculture moved to defend against this new form of attack by the Japanese. It was agreed that any balloons or other materials that were recovered would be sent to either Cal-Tech University in Pasadena, California, or the Naval Research Laboratory.

Of immediate FBI concern was the potential that the Japanese were using balloons for biological warfare. Though a valid concern, there are no known records of any Japanese personnel suggesting the use of the balloons in this fashion.

Several defensive strategies were discussed by civilian and military authorities. The Western Defense Command stationed additional planes for coastal defense and about 2,700 troops for fire fighting at critical points to protect against further balloon attacks. Further media attention was squelched to prevent heightened anxiety among the general population of the western United States and Canada.

In February 1945, the Japanese added stories of massive fires and loss of life from balloon attacks to their propaganda broadcasts. Their stories were, of course, false. The Japanese high command had received no reports regarding the results of their unmanned flights. The official silence concerning the attacks was so complete that the Japanese did not know that some balloons had, in fact, successfully made the journey across the South Pacific until the war was over.

The Mysterious End of Project Fugo

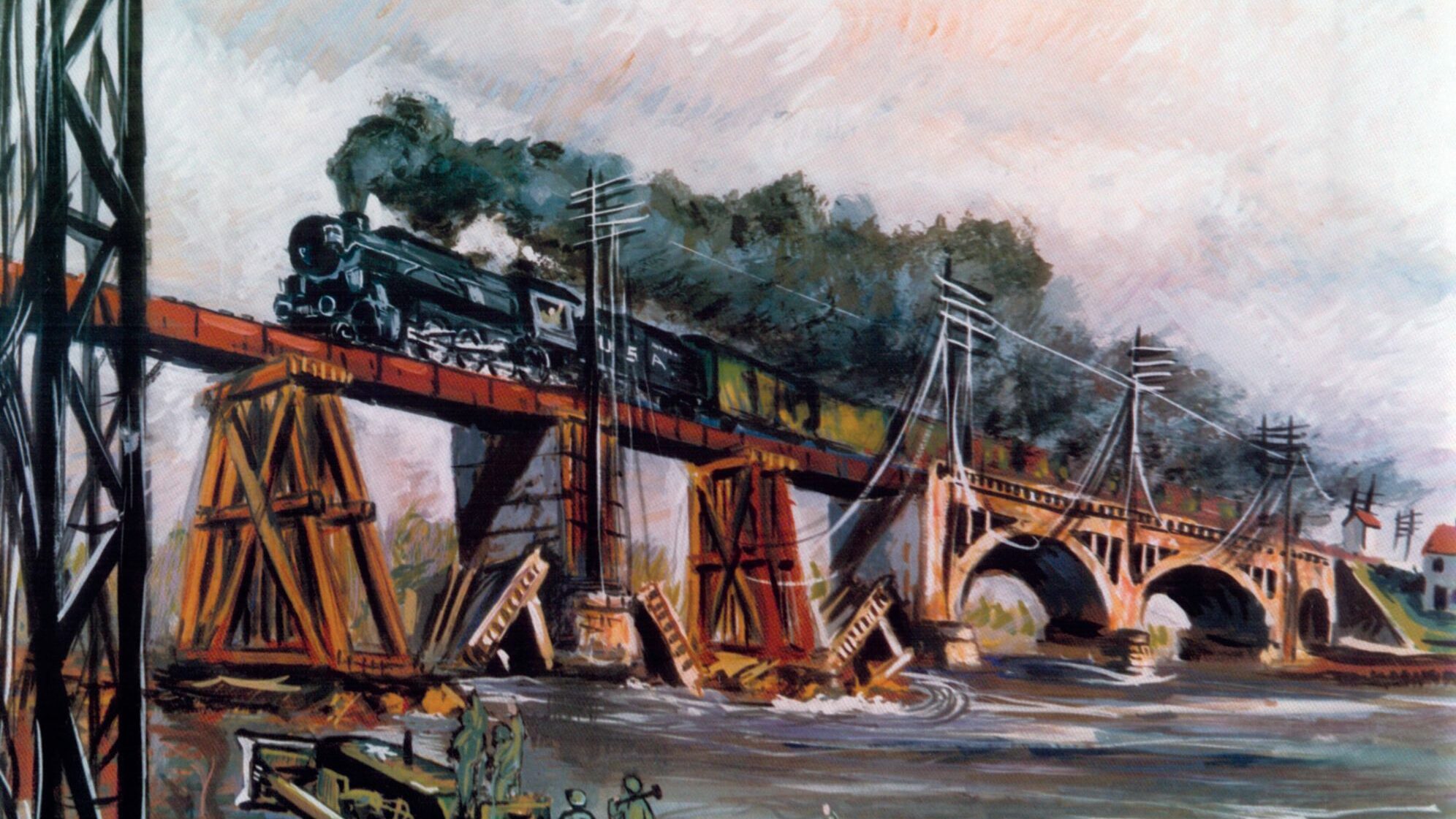

The balloon attacks continued into April 1945. By the end of that month the launches were terminated. Two possible reasons for ending the Fugo project exist. First, the Japanese high command may have thought that none of the balloons were reaching North America because of the lack of press coverage. Second, the intensive American air raids over Japan may have destroyed factories that supplied needed materials for the balloons, most notably hydrogen gas. Destruction of railroads could have made it virtually impossible to deliver the necessary supplies to launch sites.

The number of reported balloon incidents topped 300 by the time the war ended. Though most of them came down in the Pacific Northwest with 45 in Oregon, 28 in Washington, 57 in British Columbia, and 37 in Alaska, many others were driven greater distances by the jet stream. One balloon fell on a farm in Kansas, and two were discovered as far south and east Texas.

The balloon that settled on the snow-packed ground on Gearhart Mountain in southern Oregon was discovered on Saturday morning, May 5, 1945. Archie Mitchell was the new pastor of the Christian and Missionary Alliance Church in Bly, Oregon, a small lumber and ranching town. Mitchell and his wife Elyse, who was five months pregnant, had moved to Bly only a few weeks earlier. Archie had planned a short fishing trip to get better acquainted with some of his young parishioners.

Taking five local children with them, Archie and Elyse traveled to nearby Gearhart Mountain. As they traveled down a forest service road through Weyerhaeuser Timber Company land, they were stopped by a forest service road grader that had just been pulled from a mud hole by a pickup truck. The stop was a welcomed relief to Elyse, who felt a little car sick. As Archie conversed with the three-man forest service crew about road conditions and fishing possibilities, Elyse and the youngsters got out to take a stretch and look around.

Archie found out that the road was impassible. He decided to take his car back down the road a short distance and park it at Salt Spring. As Archie got into the car, Elyse called out to him, indicating that she and the youths had found something of interest. Archie called back, saying that he would come and look shortly.

Archie moved his car back down the road. Suddenly, an explosion erupted, and flying debris filled the air. After a stunned moment, Archie and the forest service crew rushed the 100 yards to where Elyse and the children had been standing. To their horror, the five children lay dead, their bodies ripped apart. Elyse Mitchell died seconds later. Where Elyse and the children had stood was a smoldering crater three feet wide and one foot deep.

Elyse W. Mitchell, 26, Jay Gifford, 13, Edward Engen, 13, Sherman Shoemaker, 11, Joan Patzke, 13, and Dick Patzke, 14, were dead. These were the only deaths attributed to enemy action during World War II in the continental United States. An explosion of “unknown origin” was the explanation given to the press by local military authorities. The area was sealed off quickly, and H.P. Scott, a U.S. Navy bomb disposal officer from nearby Lakeview Naval Air Station, recovered the four unexploded incendiary bombs, a self-destruct device, the remains of the balloon, and most of the other debris from the exploded bomb.

Did the Japanese accomplish what they had hoped with their balloon assault? From a military standpoint it was a dismal failure. The Japanese hopes of igniting a major forest fire were ill conceived. Their winter and early spring launches made the remote chance of starting a forest fire practically impossible. No documentation regarding forest fires ignited by balloon bombs exists.

The panic that the Japanese had hoped would grip the West Coast never materialized. The United States government’s prompt action to suppress information in cooperation with Canadian and local authorities was quite effective. If the Japanese had been able to develop their balloon capabilities earlier in the war, they may have found greater success.

A total of 359 incidents of Japanese balloon bombings were documented. These range from finding bomb fragments and pieces of balloon envelopes to completely intact balloons, including their bombing platforms. These recorded incidents, though some may be duplicates, represent less than six percent of the estimated 6,000 balloons that were launched. Though the majority of the balloons were probably lost over the Pacific, the possibility exists that there are still unexploded bombs in rural areas in the western United States and western Canada after nearly 70 years.

Darrell W. Coulter is a freelance writer specializing in history and science fiction. He resides in Vancouver, Washington, with his wife Rebecca and three daughters.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments