By Ken LaFayette

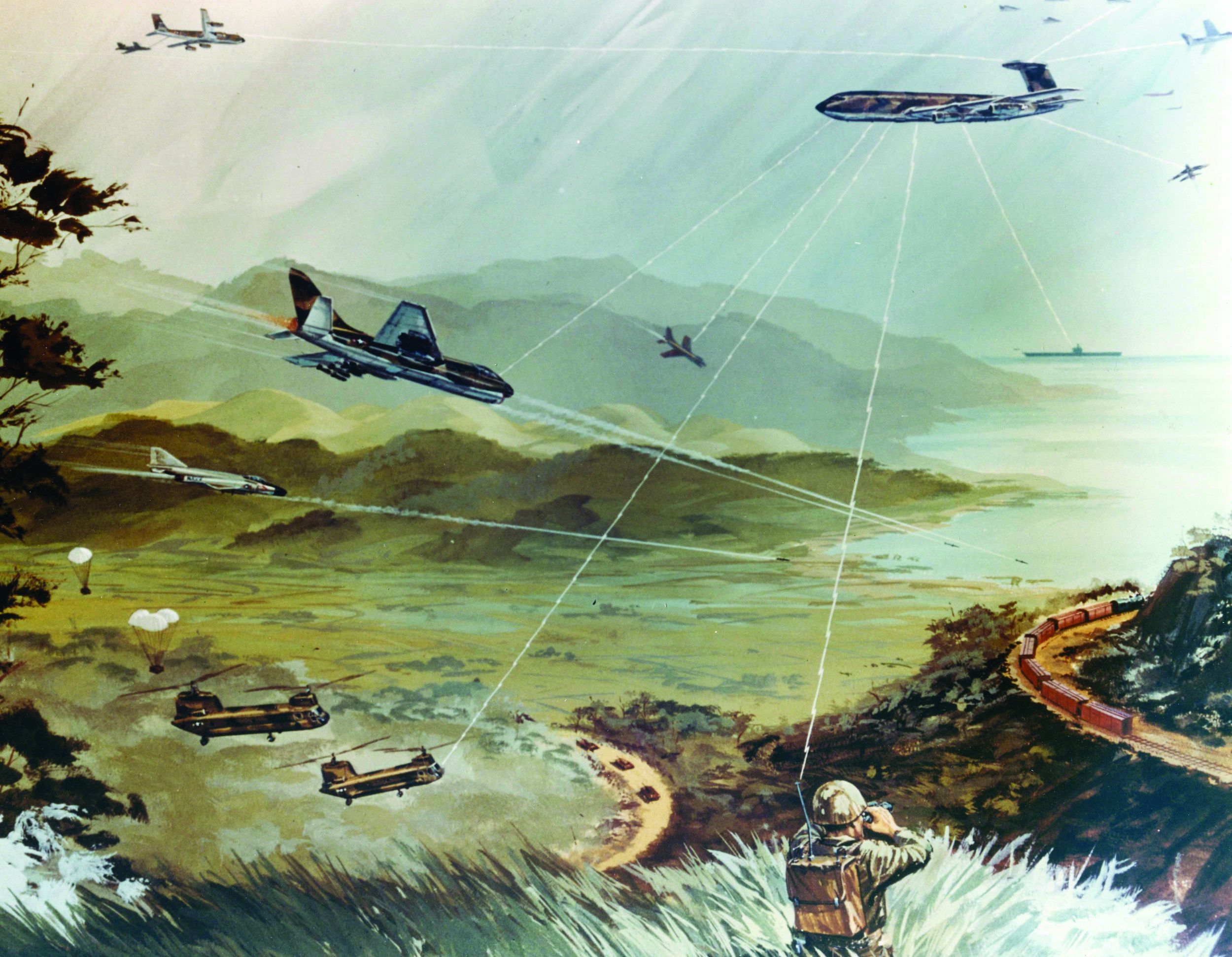

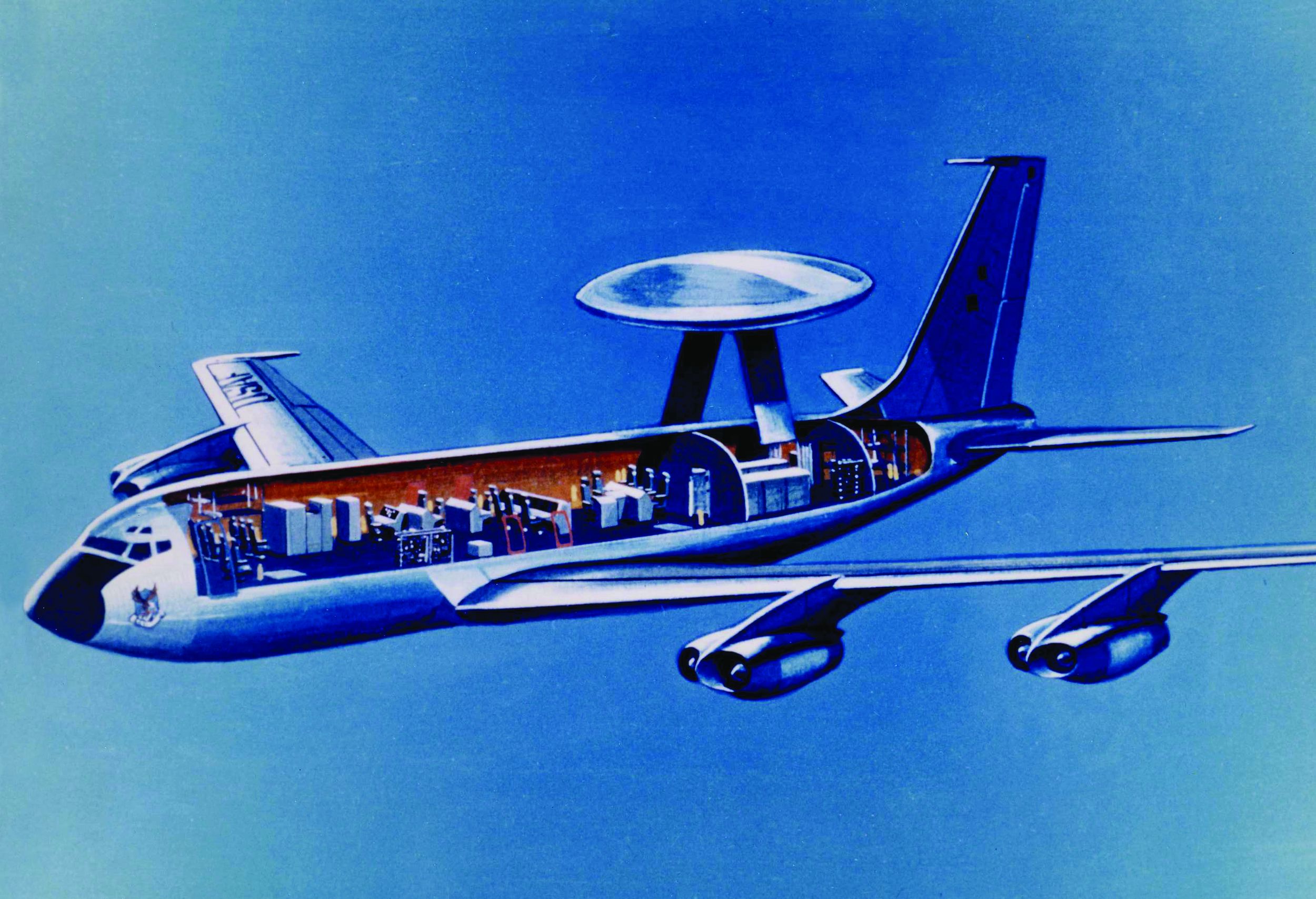

The year 2007 marked the 30th anniversary of the E-3 Sentry’s Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) service to the United States Air Force. Originally conceived as a way of overcoming the line-of-sight limitations of ground-based radar systems, the E-3 development program produced the preeminent airborne warning and control system in the world. Its arrival heralded a new philosophy in airborne combat and changed forever the concept of airborne battle management.

The history of the E-3 Sentry began when the Air Force realized that it needed a worthy successor to the EC-121 Constellation surveillance platform. The Air Force opened competition between Boeing Aerospace and McDonnell-Douglas to expand on the EC-121’s capabilities. After several trials and competitions, the Air Force awarded the contract to Boeing Aerospace.

First Flight, First Hurdles

In the 1970s, the E-3 concept began to take shape. Boeing conducted initial flight tests with competing radar packages from Hughes Aircraft Company and Westinghouse Electric Corporation. The primary obstacle was the inability of the radar-computer system to “look down” and separate aircraft signatures from surrounding ground clutter. Using the pulse-Doppler principle, the Westinghouse radar performed well enough for the Defense Systems Acquisition Review Board to continue with the development program.

Congressional approval for funding faced an uphill battle, however. Complicating the situation, the General Accounting Office published two very critical reports about the E-3 program. The GAO reported that the ability of the system to perform as stated had not been completely proven, and the E-3’s ability to survive and operate in a hostile environment remained suspect. Furthermore, the GAO criticized the ability of the AWACS to operate in an intense electronic jamming environment such as it would face in a European confrontation with the Soviet Union.

The System Integration Demonstration flights addressed the first issue concerning performance. Congress was so concerned with the electronic warfare issue that it wrote a caveat into the 1975 defense spending bill, stipulating that a special electronic countermeasures committee be formed by the Secretary of Defense to review the E-3’s ability to overcome enemy jamming. Congress also warranted a personal certification from the secretary as to the AWACS’s ability to be effective in a combat environment. That same year, the Senate and House Armed Services Committees gave their approval to the program.

Production and Deployment

Overcoming all the obstacles, the first E-3 rolled out of Boeing’s hangar in October 1976, a bare 23 months after the company had received permission to proceed with operational production. Five months later, aircraft tail number 75-0557 landed at Tinker Air Force Base, Oklahoma, and was greeted with a grand welcoming ceremony. The Air Force had chosen Tinker as the main operating base for the E-3 fleet for several reasons. Because Tinker is located in the center of the United States, its geographical position facilitated the ability of the AWACS to reach most U.S. boundaries in minimum time. Another consideration in the Tinker selection was the large industrial complex that surrounds the base. Most important was the designation of the Oklahoma Air Logistics Center as the AWACS support and depot maintenance facility, allowing the Air Force to centralize the management of the E-3 fleet, provide maximum facility and logistics support, enhance operational readiness, and reduce life-cycle support costs. A 1974 article in Air Force Magazine touted the E-3 program as the “USAF’s most successful development program.”

On March 31, 1977, the first operational flight of the E-3 took off from Tinker AFB. Operations were initiated, and the E-3 took on a worldwide commitment, assuming a readiness role in support of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD). The E-3 and its crews stood on alert, ready to fly short-notice missions to sectors along the U.S.-Canada border for airborne radar coverage in defense of the North American continent.

In 1978, the 963rd AWACS Squadron made its first operational deployment to Kadena Air Base in Japan, which would later become an E-3 operating base. Soon after AWACS began service with NORAD, NATO decided to purchase 18 E-3 aircraft for its own airborne early warning role. The same year also marked the first time that an E-3 assisted in the apprehension of an aircraft smuggling marijuana into Florida. The E-3 closed out the decade by flying its first around-the-world mission, supporting deployments in Saudi Arabia in response to rising tensions caused by the civil war in Yemen and then going to South Korea in response to the assassination of President Park Chung Hee.

AWACS in the ’80s

The E-3 began the 1980s with a deployment to Egypt in support of a joint training operation with the U.S. Navy’s Sixth Fleet. Meanwhile, the Iran-Iraq War was in full swing and the United States and Saudi Arabia were concerned that the conflict could spill over into the adjacent Gulf region. To demonstrate American resolve, the United States sent a symbol of its commitment, the AWACS. E-3s deployed to Saudi Arabia in support of European Liaison Force One (ELF-One) operations, providing around-the-clock airborne radar coverage during the entire course of the eight-year war.

In 1981, the E-3 returned to Egypt following the assassination of that country’s president, Anwar el-Sadat. Later that same year, AWACS controlled the first intercept of a Soviet Bison aircraft near Iceland. With all the increased activity, the E-3 set a fiscal year flying record by logging 26,365 hours with 24 aircraft.

In 1983, AWACS was sent to Sudan to provide airborne radar coverage as that nation repelled rebel forces near Khartoum. The E-3 also deployed in support of Operation Urgent Fury in Grenada to monitor and deter air and sea traffic originating from Cuba. Additionally, AWACS activity increased in the Pacific theater following the downing of Korean Airlines Flight 007. A few years later, E-3s were allocated to Elmendorf AFB, Alaska, where the 962nd AWACS was activated in 1986.

The decade of the 1980s ended on a positive note when the AWACS returned home from its eight-year deployment to Saudi Arabia. E-3s had flown more than 6,000 sorties and accumulated 87,000 hours in support of ELF-One. The wing expanded its mission under higher headquarters direction and began patrolling the southern border of the United States. Operation Just Cause featured E-3 participation in the invasion of Panama and the capture of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega. E-3s also began flying routine counternarcotics operations out of Roosevelt Roads Naval Air Station, Puerto Rico.

7,315 Combat Hours

During the 1990s, AWACS deployed to the Persian Gulf in support of Operation Desert Shield. E-3s executed airborne control over several of the initial air strikes on Iraq in Operation Desert Storm and played a vital role in Operation Proven Force in the Persian Gulf War. E-3 aircraft and aircrews flew a total of 7,315 combat hours during Desert Storm, sustaining a 91 percent mission-capable rate. They controlled 31,924 air sorties and lost only one Allied aircraft in air-to-air action. In addition, AWACS controlled 20,401 air refueling sorties, with tankers offloading more than 178 million gallons of fuel to 60,543 receivers. After the war, the E-3s remained in the region in support of NATO Operations Provide Comfort and Southern Watch. This steady warrior had rapidly reached legendary status as a weapon platform.

The E-3 experienced its darkest hours during the mid-1990s. Two E-3-controlled Air Force F-15s mistook a pair of U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopters for Soviet-built Hind helicopters and shot them down over the northern no-fly zone in Iraq, causing the deaths of 26 people on board the helicopters. Of the six individuals subsequently investigated for dereliction of duty, only one actually went before a court martial, and he was acquitted of all charges. A year later, the E-3 community experienced its worst internal tragedy. A U.S. Air Force E-3 AWACS, call sign Yukla-27, crashed at Elmendorf AFB. Twenty-two Air Force crewmen and two Canadian Air Force crewmen lost their lives in the crash. The Air Force later determined that Yukla-27 crashed after geese were sucked into the engines during take-off.

In the late 1990s, the first E-3 AWACS aircraft to receive the Block 30/35 upgrade rolled out at Tinker AFB. This was the largest single upgrade that the E-3 ever received. The modification upgraded the E-3’s computer memory, expanded its ability to link with other command and control platforms, and allowed the E-3 to detect emitting electronic signals. It also replaced the old navigation system with a state-of-the-art global positioning system. In another first, the Air Force Reserve activated the 513th Air Control Group. The 513th’s mission would parallel that of Tinker’s 552nd Air Control wing, providing airborne warning and control system support of combat, as well as contingency and special missions worldwide. The decade ended much as it started, with three E-3s deployed to Geilenkirchen Air Force Base, Germany, in support of Operation Allied Force. AWACS crews flew 47 sorties supporting NATO-led policies designed to deescalate the civil conflict in the Balkans.

The E-3 in the New Millennium

On September 11, 2001, after terrorists struck the World Trade Center in New York City, an E-3 was on-station to provide airborne surveillance over the eastern seaboard within 30 minutes of the attacks. AWACS began flying 24-hour orbits over American skies in support of Operation Noble Eagle to prevent further terrorist attacks.

In 2002, the E-3 logged its 10,000th flying hour in support of Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. Months later, the wing received deployment orders to support Operation Iraqi Freedom, sending an additional 45 troops into the region. By the middle of 2003, the first AWACS deployed to OEF and OIF returned to Tinker AFB. While deployed, E-3s flew more than 188 sorties and logged 1,900 flying hours in support of the ongoing war against terrorism. The return of America’s wing ended a 13-year continuous presence in the region, and for the first time in 25 years, all 28 E-3s were back at their home station.

In 2004, things started to pick up again as AWACS was called upon to aid civil law enforcement agencies in stopping the flow of illegal drugs from Latin America into the United States. E-3s were forward deployed to Manta, Ecuador, as crews and support personnel were integrated into Aerospace Expeditionary Force cycles. Meanwhile, E-3 squadrons also responded to a national-interest mission to support world leaders during a summit meeting in Santiago, Chile.

In 2005, the E-3 received another major upgrade—the Radar Systems Improvement Program—which increased the aircraft’s ability to detect cruise missiles, while providing 200 percent greater flight coverage volume. Later that year, national authorities again relied on this proven warrior by requesting eyes-in-the-sky protection for the U.S. president during his visits to the Netherlands, Russia, and Tblisi, Georgia.

In September 2005, the E-3 was called upon to assist federal agencies in coordinating relief efforts for both civilian and military aircraft in the devastated areas of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana caused by the category 5 hurricane, Katrina. The wing flew 16 sorties, amassing 158 flying hours. Less than a month later, the wing began flying support missions to Hurricane Rita relief efforts. This category 4 hurricane affected areas in southeast Texas and southwest Louisiana, where the wing flew 14 sorties and amassed 118 flying hours. Shortly after flying hurricane support missions, AWACS deployed to Mar Del Plata, Argentina, for another presidential support mission during the Summit of the Americas.

The year 2006 began with more system upgrades. The Integrated Demand Assigned Multiple Access Satellite Communication (DAMA) and Global Air Traffic Management (GATM) programs, collectively called IDG, provide air traffic management among civilian and military aircraft.

The E-3 took part in testing Tactical Target Network Technology (TTNT) radios, which are expected to make possible future communication between ground and air assets via digital networks. AWACS also wrapped up its busiest aerospace expeditionary force cycle since Iraqi Freedom, performing missions in Japan, the Caribbean, South America, and the United States.

Over the last 30 years, AWACS has exemplified combat excellence, partnership, and innovation. During the next 30 years, it is expected to continue leading the way in global vigilance, global reach, and global power. Improvements will continue to be made. Soon, AWACS will emerge into a new platform that will combine its capabilities and the capabilities of other intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance airplanes in the ongoing fight against terrorism and other threats, both foreign and domestic.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments