By Raymond E. Bell, Jr.

You won’t find the familiar little triangular signs, “Warnung Minen!” hanging on barbed wire today in Western Europe, with one exception. You might well see them on a garden fence in the vicinity of the small town of Harlange in northwestern Luxembourg, which lay directly in the path of the U.S. 6th Armored and 35th Infantry Divisions during the liberation of Luxembourg.

Today the town sits peaceably in the bucolic countryside, with scarcely a trace of the destruction wrought by the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. But on the second floor of Deputy Chief of Police Gilbert Hoffmann’s home is a unique and compact museum of World War II weaponry, personal equipment, communications gear, uniforms, and other military memorabilia.

A Very Personal Museum

To many World War II veterans and their families who have visited Luxembourg in recent years, Hoffmann is a well-known military expert with an intimate knowledge of the terrain and environs of northwest Luxembourg. A veteran of that nation’s small army and gendarmerie, Hoffmann for many years has walked the local battlefields on the southern flank of the German advance during the Battle of the Bulge. His work as a gendarme led to close connections to local inhabitants and Hoffmann has collected a large and diverse selection of wartime memorabilia. He happily shares this collection with interested visitors (by appointment only, for security reasons).

Hoffmann and his wife, Diane, greet visitors warmly at the front door of their gracious home overlooking Harlange—once you get past the signs warning about the mines. Mme. Hoffmann is an accomplished cook, but like her husband she also collects World War II memorabilia. Vintage cigarettes, ration cards, razors, tubes of shaving cream, P-38 can openers, and matchbooks sit inside a handsome glass case in the home’s vestibule.

On the second floor of the Hoffmann home, visitors immediately see the sign reading “Captain James D. Richter Memorial Collection” on the secured door at the end of the hall. Richter was the artillery liaison officer for the 915th Field Artillery Battery, 359th Infantry Regiment, 90th Infantry Division in January 1945. He was killed by a German Minenwerfer round while crouched at the blown-out window of a farmhouse on the outskirts of the Luxembourg hamlet of Nothum on January 9.

The 90th Division was just commencing an attack against the German 19th Volksgrenadier Division when Maj. Gen. James A. Van Fleet and his entourage arrived at the house to view the attack’s launching. Keen German observers noticed the convoy of jeeps arriving at the farmhouse and quickly zeroed in on it. The author’s father, Colonel Raymond E. Bell, the regimental commander of the 359th Infantry, was standing in a doorway adjacent to the window and narrowly missed being hit by the shell. Richter, unfortunately, was fatally struck by shell fragments flying through the window.

Hoffmann got to know the Richter family after the war when Captain Richter’s two sons came to Luxembourg in search of their father’s place of death. The then Gendarme Hoffmann had been scouring the countryside for abandoned German and American weapons, ammunition, and equipment that littered farmers’ fields in the area. Stationed in the village of Bavigne, a few miles from Harlange, Hoffmann and his interest in World War II memorabilia were well known in the surrounding communities, and he and the Richters quickly linked up.

Just inside the door, on the wall, is a photograph of the author’s father as a colonel commanding the regiment to which Captain Richter was liaison officer. On display also are Colonel Bell’s stars from when he was promoted to general; his ribbons, including the Distinguished Service Cross and four Silver Stars; and his brigadier general’s shoulder boards for his formal blue uniform.

Radio, Artillery, and the Palace Hotel

The first exhibit one sees in Hoffmann’s attic museum is the “radio corner.” There is displayed a radio set labeled Signal Corps Radio-300A. Beside it, in front of a 12-line BD-72 telephone switchboard, is a mannequin dressed in the uniform of a technical sergeant of the 359th Infantry Regiment, 90th Division. To his right is a BC-659 Signal Corps transmitter.

In the room, the visitor also notes a touch of the present day. Hanging on the wall is a Belgian-made FN-FAL light automatic rifle, a weapon that played a prominent role in the decades-long confrontation between Western and Communist troops on the border of East and West Germany. The weapon, firing the standard 7.62mm cartridge, was the rifle of choice for many North Atlantic Treaty Organization member nations. It was also popular in countries as far apart as Peru and Burundi.

Located just below the rifle is a row of shells for light artillery pieces in the range of 105mm caliber. Of particular note are the dreaded German 88mm antitank and antiaircraft cannon shells for the lethal Flugabwehrkanone 41 (FLAK) antiaircraft gun. Alongside the 88mm shells sits one for the Panzerabwehrkanone 43 (PAK) antitank gun, which by the end of World War II packed twice the amount of propellant as the original version of the weapon.

While the disarmed shells are interesting, what is perhaps more significant in the display are the two aiming circles, American and German, that allowed gunners to put their rounds accurately on target. American artillerymen, in particular, were quite accurate in their fire direction. Part of the reason was that the American M1 aiming circle was more precise than its German counterpart. That is all the more remarkable because of the German reputation for producing excellent optical equipment. The German Richtkreis 1940, however, had a 5 mil deviation error, which meant that at the range of 10 kilometers an artillery round would land at least 500 meters wide of its target. While German artillery could be fearsome at times, this deficiency in accuracy undoubtedly had an adverse effect on the results produced by German gunners.

On the other side of the museum, one encounters a more peaceful display—two wine glasses with the letters “PH” engraved on them, standing for the Palace Hotel in the southern Luxembourg town of Mondorf. The hotel was a prisoner-of-war holding location for especially notorious Nazi war criminals awaiting movement to Nuremberg for the famous trials. German air czar Hermann Göring, for one, spent time at the hotel before he was placed on trial. The Allies did not want the hotel to become a rallying site for Nazi adherents after the war, so the hotel was destroyed. Hoffmann managed to salvage two of the heirloom wine glasses from the general destruction.

Weapons of the War

One of the most interesting parts of the museum is its display of German weapons, uniforms, and equipment. Here, one finds the famous German machine gun, MG-42, which had a very high rate of fire. On the battlefield, it was easy to distinguish the firing of the weapon from the American light machine gun because of the German weapon’s distinctive sound. On display also is an MG-15 aircraft machine gun used by German paratroopers on the ground after they added a bipod and butt stock.

The Luftwaffe plays another role in the exhibit of German equipment at the Hoffmann Museum. German parachute troops wore a belt with brown leather pouches and a belt buckle with a Luftwaffe insignia on it. Inside the belt on display are the markings “FLGF.SCH.CL LUST, 2te KOMPANIE,” indicating that the wearer was in flight-pilot training school before going on to become a Fallschirmjaeger, or paratrooper.

Poison gas was not used on World War II battlefields by any of the combatants, but both sides were prepared for such warfare, and the preparation extended to children. The Germans developed a gas protective jacket for children too small to wear the standard gas mask. One of these jackets is on display in Hofmann’s collection.

For the small-arms aficionado, there is an exhibit of the 70 different types of German small-arms ammunition. Examples include the black-tipped round that indicated a tracer round used for night firing, and a wooden-tipped round used as a blank or practice round. Other examples include the armor-piercing tracer round used in the tropics, the armor-piercing phosphorous round, and the propelling cartridges used for antitank grenades. Of special note is the cutaway of a fused round that was employed for observation and ranging purposes.

Among the displays are several types of German mines. One is the glass mine with explosives encased in a sealed glass bulb. The waterproof mine could be found on the invasion beaches of Normandy. It was designed to explode as Allied troops rushed ashore or to disrupt over-the-beach logistics operations once the landings had taken place. There is also the “Schu” mine, an explosive device designed by the Germans to “jump” when detonated. This was a particularly insidious mine because stepping on it meant losing a leg, at minimum, and often the entire lower part of one’s body. The American soldier particularly feared this mine for its disabling effects. During the harsh winter of 1944-1945, however, the detonating mechanisms on such mines often froze when covered with snow and ice, so that a soldier stepping on the mine would not cause it to explode. When the snow and ice melted, however, the mines resumed their deadly roles. Rear-echelon troops advancing behind combat forces that had bypassed the mines during the winter suffered accordingly.

Hoffmann personally found or recovered many of the items in local fields and buildings. Neighbors would call him when they discovered war items, and he would see to it that they were properly disposed of. Some of the items were found in unusual places. A Panzerfaust, or German bazooka, was discovered in the chimney of a local home. To this day Hoffmann finds wartime relics in woods where shrapnel still lies freely on the ground.

Tributes to the Soldiers

The museum, as noted, is dedicated to Captain Richter, but another officer also haunts the collection. On the same day, at the same time, that Richter was killed, Lt. Col. George B. Randolph, the battalion commander of the 712th Tank Battalion, was killed instantly by a piece of shrapnel from a Nebelwerfer round as he stood beside one of his tanks just a few yards from where Richter lost his life. Hoffmann has memorialized Randolph by creating a mannequin dressed as Randolph was dressed when he was killed, complete with helmet and overcoat.

Next to Randolph’s mannequin stands another one representing a soldier of the 5th Infantry Division, which held part of the southern shoulder of Maj. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army during the Battle of the Bulge. This mannequin appears, wearing a long overcoat, fully uniformed as he arrived in the theater of operations. Another mannequin is dressed in an early 1945 camouflage uniform, accessorized with a harness used for carrying boxes of machine-gun ammunition, two in front and two in the rear.

The United States is not the only Allied nation represented in Hoffmann’s museum. A Luxembourg artillery unit firing a 105mm/25-pounder artillery piece is on display as well, represented by a Luxembourg soldier wearing British battle dress and a Luxembourg shoulder tab. The unit was integrated into the Belgian Piron Brigade, and it used British equipment and uniforms such as the Belgian soldiers wore.

Heavy Weapons and Bayonets

Hoffmann manages to display his weapons, many still serviceable, along with ammunition and mines, by having a Luxembourg Department of Justice inspector inspect his collection yearly for proper security and storage. One has to wonder what the inspector must have thought when he first saw the original 20mm German automatic antiaircraft cannon, the FLAK 38, mounted on a wheeled chassis in Hoffmann’s garage. The inspector must also have been impressed by the almost complete collection of World War II bayonets on display. The only one missing is the chrome-covered bayonet that West Point cadets carried on the barrels of their M1 rifles in the 1940s and 1950s.

As one continues to tour the museum, one encounters American 60mm and 81mm mortars. The 81mm mortar was employed in the heavy weapons company of an infantry battalion and could fire a diverse array of rounds. The smaller 60mm mortar proved effective at close ranges, but after World War II it was abandoned by the U.S. Army because of its perceived ineffectiveness.

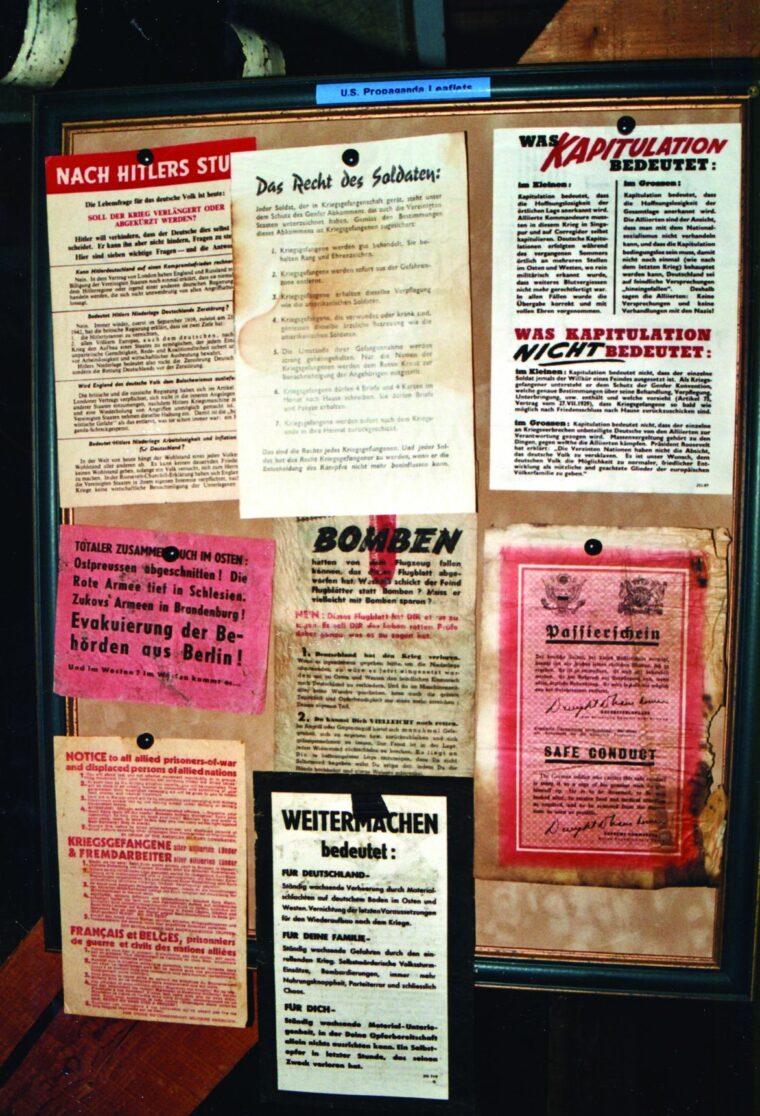

Propaganda and Helmets

Hoffmann’s collection of wartime propaganda is especially interesting. The German leaflets exhibited were very crude and written in poor English. The American leaflets, on the other hand, many of which were dropped by aircraft as well as blasted into enemy lines via artillery rounds, were very detailed and professionally done. Probably the most significant piece of American psychological weaponry was the safe conduct pass. On one side, safe passage was printed in German, on the other in English. These proved quite popular with the Germans as the Allies beat down the foes’ defenses and swept into Germany proper in early 1945.

Departing the museum, one sees various helmets on display. One is the U.S. antimagnetic helmet worn by air crew gunners in B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberator bombers. These were worn to keep from disturbing the aircrafts’ delicate compasses. Of special interest to the son of a 90th Infantry Division officer is the helmet clearly marked with a “TO” (for Texas-Oklahoma) found near the hamlet of Nothum. Through the helmet’s right side one can see where a round went in and came out the back in the form of two shell fragments. Its owner’s fate is unknown, but it is possible that the bullet was deflected around the inside of the helmet’s plastic liner. One can only hope.

A Family of Collectors

Mr. and Mrs. Hoffmann are not the only military memorabilia collectors in their family. Thirteen-year-old daughter Kathy has a nice collection of her own in the Hoffmanns’ attic museum. In a number of cans she has collected pieces of shrapnel that she personally dug up in the fields. She has also assembled a variety of cartridges from small arms, most displaying years of exposure to the ravages of nature. She has placed these in an ammunition box that she found near the World War II memorial chapel on the outskirts of Harlange. At Schumann’s Eck, a small piece of ground where U.S. Army divisions fought on the southern flank during the Battle of the Bulge, Kathy found a large piece of shrapnel. She has added this to her display, along with a .50-caliber cartridge that her father believes was dropped by an American aircraft strafing a German position. Still another memento is the tail assembly of a 60mm mortar shell used by an American infantry heavy weapons platoon.

There is a plethora of World War II museums in Belgium, France, and Luxembourg that celebrate the remarkable victory over Germany. Some are comprehensive and elaborate, such as the ones at Diekirch, Luxembourg, and Thionville, France. Others are more memorials than museums, such as the one at Bastogne, Belgium. Many private homes are also undoubtedly repositories of World War II memorabilia, but Gilbert Hoffmann’s attic museum is one of the best of these small museums. As a bonus, the owner is a hands-on expert on what he displays. Hoffmann can be contacted by e-mail at musee-ardennes@internet.lu.

I have a WW2 helmet M40 Stapped with Ef64

With a name of F w. Hoffmann on the inside of it.