By Arnold Blumberg

With the fall of Vicksburg in the first week of July 1863, the strongest remaining Confederate presence in Mississippi was a recently thrown together force of 26,000 soldiers under General Joseph E. Johnston at Jackson. Determined to remove all organized resistance in the Magnolia State, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant ordered his most dependable subordinate, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, to take 40,000 men and drive Johnston and his army completely out of Mississippi. Leaving Vicksburg on July 4, Sherman occupied Jackson on July 19. Upon Sherman’s approach, Johnston headed for the town of Morton, 30 miles east of Jackson. After reoccupying Jackson (he had taken the city the first time on May 14, during the Vicksburg campaign), Sherman ordered his men to devastate the area’s war-making potential by ripping up railroads, burning enemy supply facilities, and destroying much of the city itself. By doing so, Sherman hoped to prevent that portion of the state from ever again becoming a base of operations for the Confederates to threaten the Union’s hold on the Mississippi River.

Meridian: An Attractive Target

As Jackson burned, Sherman gazed south and saw another point on the map whose capture might complete his plan for domination of the state. The hamlet of Meridian, 100 miles east of Jackson near the Alabama border, contained one of the largest concentrations of Confederate military stores, maintenance shops, and warehouses in the western Confederacy. Meridian was a hub for Confederate traffic through Mississippi to the rest of the South. Meridian stood at the junction of the Mobile & Ohio, Southern Mississippi, and Alabama & Mississippi River Railroads—crucial lines used to transport vast amounts of men and supplies. It was little wonder that Sherman viewed the seemingly insignificant speck on the map as a prize well worth eliminating.

Although he was eager to move on Meridian in the summer of 1863, Sherman was deterred from doing so for a number of reasons. First, Grant wanted to attack the important port city of Mobile, Ala., and considered any major diversion of Union resources to be out of the question. Second, the Lincoln administration’s attention had been drawn southwest to Mexico and the perceived threat from France, which had installed a puppet government in Mexico City. Washington wanted a major effort to reestablish Federal control in Texas as the surest way to keep Emperor Napoleon III from making trouble south of the Rio Grande. Finally, the defeat of the Union Army of the Cumberland at the Battle of Chickamauga on September 19-20 and the subsequent siege of nearby Chattanooga required massive Federal efforts to relieve the city. Grant and Sherman both rushed to Chattanooga, and any further move on the interior of Mississippi was impossible in the last half of 1863.

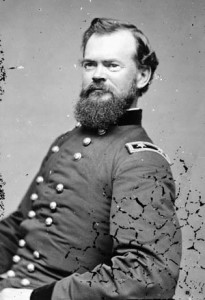

The defeat of the Confederates at Chattanooga in November 1863 allowed the Federals to look again at the removal of enemy threats on the Mississippi River. To that end, Sherman was given permission at last to implement his Meridian plan. By the time he reached Memphis, Tenn., on January 21, 1864, the general’s scheme was ready to be put in motion. Sherman intended to march on Meridian with 20,000 infantry and a brigade of cavalry. Sixty artillery pieces would complete his force. Maj. Gen. Stephen A. Hurlbut would lead 10,000 men from his XVI Corps southward from Memphis to Vicksburg and join a like number of men from Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson’s XVII Corps. Colonel Edward F. Winslow’s 2,500-man mounted brigade would serve as the expedition’s eyes and ears. From Vicksburg, the Union force would move to Meridian and, depending on circumstances, perhaps advance to capture Selma, Ala., as well. To fend off the almost certain interference from the redoubtable Confederate cavalry leader Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, then operating in northern Mississippi, a 7,000-man cavalry division under Brig. Gen. William Sooy Smith would depart Memphis just before Sherman’s main body left Vicksburg and move south along the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, destroying the road as it went, and meet up with Sherman at Meridian.

Sherman’s raid on Meridian was to be a large-scale attack designed in part to devastate the transportation facilities and resources of the region. Occupation of territory was not an objective and, as a result, the Federal force would not have to depend on lengthy supply lines to sustain itself. Since the expedition was meant to be only a temporary foray into enemy country, Sherman’s men would be able to live off the land as they went. Sherman himself was full of confidence. “I think in all January and part of February I can do something in this line,” he told Grant. “To secure the safety of the navigation of the Mississippi River I would slay millions. I think I see one or two quick blows that would astonish the natives of the South and will convince them that, though to stand behind big cottonwoods and shoot at a passing boat is grand sport and safe, it may still reach and kill their friends and families hundreds of miles off. For every bullet shot at a steamer, I would shoot a thousand 30-pounder Parrotts into even helpless towns on the Red, Ouachita, Yazoo [Rivers], wherever a boat can float or a soldier march.”

Marching on Meridian

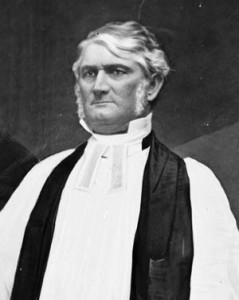

On February 3, the Federal advance to Meridian commenced as two long blue columns, Hurlbut on the left and McPherson on the right, departed Vicksburg heading for the Big Black River. Opposing the Union move was the recently created Confederate Army of the Mississippi under Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk, an Episcopal bishop, West Point graduate, and close friend of Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Polk’s infantry division commanders in the nascent army were Maj. Gens. William W. Loring and Samuel G. French, with Maj. Gen. Stephen D. Lee and Forrest leading his cavalry. All told, Polk could muster around 10,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry to contend with Sherman’s threat.

Hearing of the enemy concentration at Vicksburg and fearing that this meant an imminent offensive, Polk began to fortify key positions in Mississippi to block or delay any Federal advances into the eastern part of the state. Loring was instructed to build works at Canton, north of Jackson, while French was to dig emplacements in the state capital itself. Polk made no attempt to concentrate his forces. Instead, he tethered his infantry to several pockets in the Jackson area and allowed Lee’s cavalry to remain scattered between Jackson and the Yazoo River, while Forrest’s troopers remained in the northern part of the state.

By February 4, the Union cavalry leading Sherman’s advance reached the Raymond Road just ahead of McPherson’s plodding column. Passing near the old battlefield at Champion’s Hill, the horsemen were attacked by two regiments belonging to Confederate Brig. Gen. Wirt Adams. A brisk mounted charge by the graybacks was repulsed, sending the attackers back toward Bolton Depot. Later that afternoon, Winslow’s troopers again made contact with Adams’s men, driving them back across Baker’s Creek east of Bolton Depot. To the south, on the Bolton Road, another outfit belonging to Adams’s brigade—Colonel Robert C. Woods’s Mississippi cavalry regiment—skirmished with the head of McPherson’s infantry column. A day-long running fight developed for more than 10 miles, with the Federals slowly pushing the Confederates back.

South of McPherson’s formations, Hurlbut’s men spent the day vying with Southern cavalry under Colonel Peter Starke, supported by two artillery pieces, along the Bridgeport Road leading to Bolton Station. Union infantry and a battery of guns finally pried the Confederates out of their blocking position and forced them to retire to Clinton, farther east. Losses on both sides numbered fewer than 20 men each.

The morning of the 5th found McPherson’s brigades toiling along the Clinton Road. Ahead of them, Adams had posted his 800 men and several cannon atop a hill about 750 yards east of Baker’s Creek overlooking the wooden bridge spanning the water. On reaching the creek, Federal infantry rushed in to the water, gained the opposite shore, and formed a line of battle. Their progress was little hindered by the enemy artillery since most of the fire directed at them fell short. An hour-long artillery and musket barrage then fell on the Confederate position, causing them to move back through Clinton after joining their comrades from Starke’s command. At noon the Union cavalry entered Clinton. Jackson, 12 miles away, would be their next objective.

Sherman’s Fiery March Continues

As Sherman’s men neared the state capital, French started to move the stockpiled war materiel by rail to Meridian. He also ordered Adams to arrange his command so that his troops could cover French’s withdrawal from Jackson east over the Pearl River. Joined by Starke’s troopers, the Southern forces under Adams and Starke, numbering about 1,300 men, continued to skirmish with McPherson’s and Hurlbut’s advancing Federal infantry, which had merged at day’s end and was marching in from the west.

Leaving the road to the infantry, Winslow took off across county toward the north, circled Adams’s left and got between the Confederate cavalry and Jackson during the night of February 5. Dismounting his 4th Iowa Volunteer Cavalry Regiment to fight on foot and sending his 11th Illinois Cavalry Regiment on a hell-for-leather saber charge, Winslow scattered the unsuspecting Confederate horsemen. Starke fled north and Adams raced into Jackson with Winslow in hot pursuit. By sundown all Confederate forces had abandoned Jackson, and the blue cavalry was soon joined by their infantry comrades.

Surprised by the enemy’s rapid approach, Polk directed a concentration of his dispersed forces at Morton, 17 miles east of Brandon on the Southern Mississippi Railroad. Frantic- ally he wired Lee and Forrest, urging them to mount immediate raids on Sherman’s supply lines while he gathered his infantry to confront the invaders head-on. After destroying any remaining military stores and rail property, the Federal army moved out of Jackson early on February 7, crossing the Pearl River on a pontoon bridge and taking the Brandon Road with Winslow’s cavalry in the van. They reached Brandon later that day and burned it to the ground.

Polk Misreads the Union Advance

Meanwhile, French’s and Loring’s infantry entered Morton and began to dig in, while Lee’s and Adams’s cavalry dogged the Federals’ southern flank and Starke followed in the rear. Polk, who mistakenly believed that Sherman’s real objective was Mobile—despite a warning from Lee that Meridian was the Union goal—fired off repeated pleas for reinforcements to Joseph E. Johnston at Dalton, Ga., and P.G.T. Beauregard at Charleston, SC. Beauregard sent back word that he had no aid to give; Johnston never even bothered to reply.

On February 8, Sherman’s men departed Brandon for Morton, halting four miles from their objective that evening. Waiting for them in Morton was the combined Confederate infantry of Loring and French, which was entrenched two miles west of the borough. Loring, in overall command, hoped to delay the enemy advance while Lee’s cavalry struck the bluecoats from the rear. By the end of the day, however, Loring changed his mind. Realizing that Polk was not going to send him any reinforcements, Loring pulled up stakes and marched his men east toward Newton Station. Early the next morning the Union advance guard entered Morton, burned the town’s principal buildings, and demolished railroad tracks and bridges in the area.

The next day Polk joined Loring and French. Still fearing that Mobile was Sherman’s real goal, he directed half his available force under Loring to Mobile, while French was ordered to continue to Newton Station. As the Confederate forces split off in different ways, Winslow’s troopers engaged in running skirmishes with the gray rear guard under Colonel W.L. Maxwell along the Brandon-Hillsboro Road. The 11th saw Maxwell’s men moving back over an area filled with river bottoms, crisscrossing streams, and low-lying swamplands. Burning causeways and bridges as they retreated, Maxwell’s men seriously delayed the Federal advance to Decatur, from which point Sherman intended to quickly move on Meridian, destroying the Southern Mississippi Railroad as he went.

By now even Polk realized that Meridian was in immediate danger. He started moving all the public property he could by rail to Demopolis, Ala. While Polk acted the part of a glorified stevedore, Lee determined to do what he could to halt the Union thrust at Meridian. To that end, he sent Colonel Samuel Ferguson and his small cavalry brigade from Newton Station to add its meager strength and slow Sherman’s progress. Ferguson was forced back by Winslow after a short, sharp combat. Seeing that they could not halt the enemy, Lee and Loring headed toward Meridian just in front of the blue juggernaut.

Burning Down Meridian

On the 13th, Sherman determined to make a rapid descent on Meridian. Leaving his 600 wagons and their 4,000 horses and mules behind, he ordered the men to carry only the essentials and five days’ rations. An early start brought the Northerners to Tallahatta Creek, 15 miles west of Meridian, where they easily pushed back Lee’s cavalry. As the main body advanced directly toward Meridian, a column of four infantry brigades and some cavalry headed north to Chunky Station to eliminate the rail line there. In the process they battered Wirt Adams’s cavalry and captured three of his artillery pieces. The next morning, Winslow’s horsemen crossed Tallahatta Creek, and with the aid of Union infantry from Brig. Gen. A.J. Smith’s division, sent Ferguson’s and Starke’s riders streaming through Meridian in retreat. Smith occupied the town soon after. As the Federals reached Meridian, Loring and French started for Moscow, Ala., to the east.

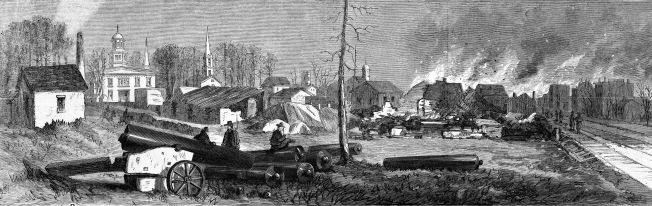

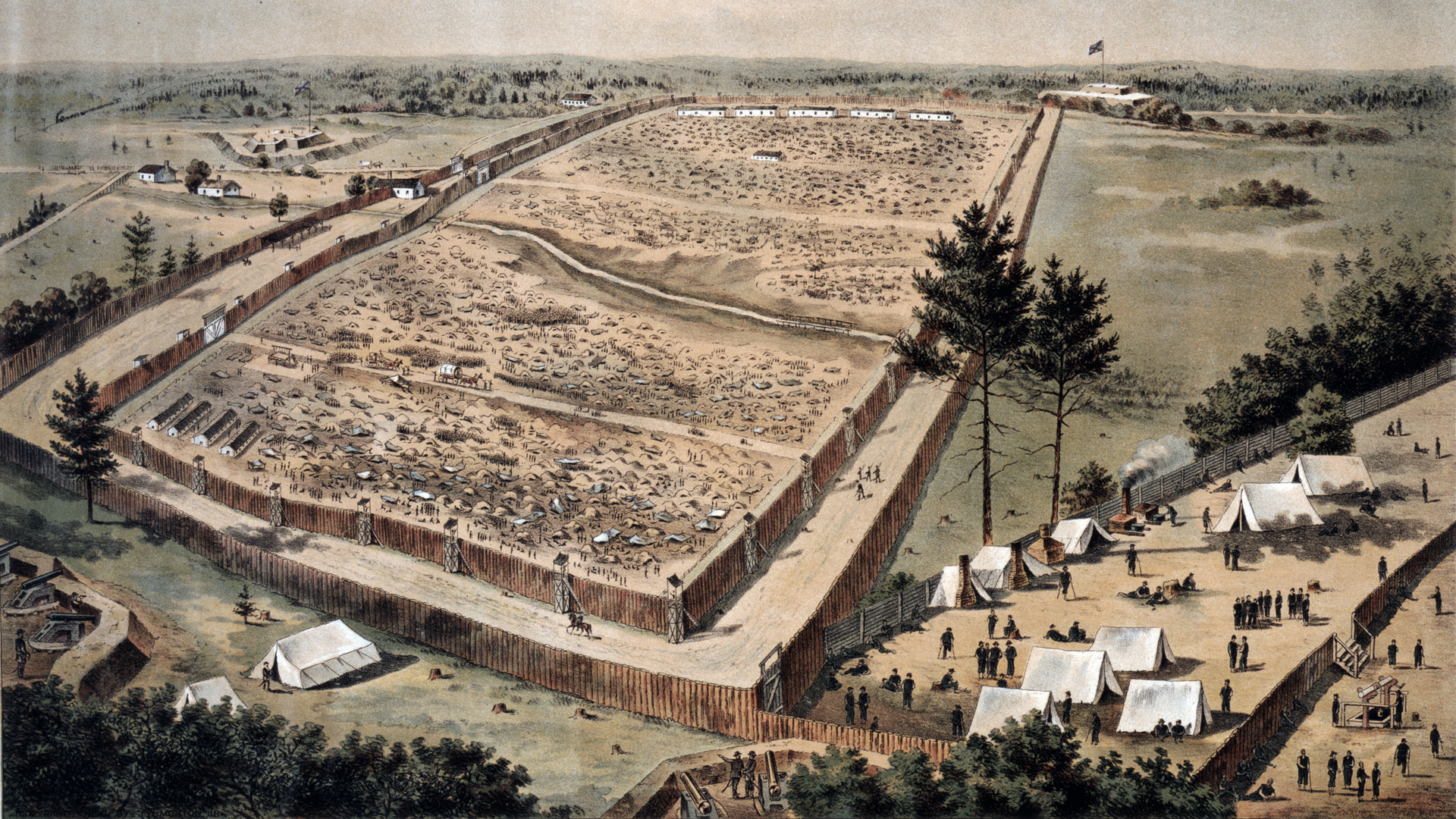

The Meridian that Smith’s men entered on February 14 had a population of 400 souls, 100 homes, four hotels, two churches, two inns, and four small dry goods stores. What made the tiny Lauderdale County town militarily important were the locomotive repair shops, the small arsenal that turned out rifles and pistols, two gristmills, and scores of wooden buildings containing war materials of all descriptions. The town’s destruction began the next day and continued for five more days. The machine shops and warehouses were set on fire and the tracks and ties of the rail lines surrounding Meridian were torn up.

The neighboring towns of Enterprise, Marion Station, and Quitman were also hit by Federal burning parties, who consigned vast amounts of lumber and cotton to the flames. Other Federal forces conducted raids on nearby farms, seizing foodstuffs, cattle, and grain. Whatever they could not carry away they burned or slaughtered. Sherman wanted the forage expeditions not only to help feed his men but also to deny the bounty to the Confederates. He drew a biblical parallel to his destruction: “Satan and the rebellious saints in Hell were allowed a continuous existence in Hell merely to swell their just punishment,” Sherman said. “To such as would rebel against a government as mild and just as ours in peace, a punishment equal would not be unjust.”

Sherman’s Withdrawal

Throughout the week Sherman spent bringing hell to Meridian, the Confederate cavalry under Lee could do no more than harass the columns of Federals that roamed the area. A concerted attack on the Federal wagon train left behind at Tallahatta Creek was attempted, but was beaten off. On the 17th, while Lee’s cavalry moved north to Lauderdale Springs, Jefferson Davis personally ordered four infantry divisions from Johnston’s army at Dalton to join Polk.

The next day, unaware of the Confederate efforts against him and still unclear about the whereabouts of the supporting cavalry force under Sooy Smith, who was to have been at Meridian before him, Sherman decided to return to Vicksburg. He reasoned that without Smith’s mounted force he could not proceed into Alabama to destroy more rail lines. Even more pressing, Sherman’s men were growing hungrier, despite their foraging at Meridian. The absence of a supply line was forcing Sherman to pull back—something the Confederates had not been able to accomplish. Sherman’s withdrawal began on February 20, passing north of the Southern Mississippi Railroad. As the army marched, Sherman sent patrols to the north, east, and west looking for Smith’s errant horsemen. Although Rebel cavalry continued to hang on the Federal flanks as they trudged west, most of Lee’s troopers headed north to Starkville to link up with Forrest.

Sherman had expected that after his forces reached Meridian, they would be joined by Sooy Smith’s 7,000-man cavalry division, which was to have left Memphis for the 250-mile trip to Meridian no later than February 1. Sherman wanted Smith to destroy the Mobile & Ohio Railroad as he advanced as well as protect the army’s main column from the unwanted interference of Forrest’s cavalry. Smith was scheduled to rendezvous with Sherman at Meridian on February 10. Sherman had warned Smith prior to the raid to avoid any “minor affairs” with the enemy as he traveled south to Meridian.

Smith Skirmishes with Forrest

Instead of promptly departing Memphis as he was ordered, however, Smith remained in the city until the 10th to give a late-arriving brigade time to rest. Leaving Memphis on the 11th, he moved through New Albany, Panola, and Abbeville in the hopes of concealing his true destination and purpose. He could have saved his men the effort. Smith and his men were tracked every step of the way by the wily Southern cavalry leader.

By February 13, Smith’s command had crossed the Tallahatchie River at New Albany after traveling slowly through the heavily timbered and swampy lowlands of northern Mississippi. The first contact with the enemy occurred that day when Smith’s troopers met and dispersed a force of 600 state militia near Pontotoc. The snail’s pace of the Union force continued as it crossed numerous swamps and creeks overflowing with winter rains. More threatening, the Federal flanks and rear came under repeated attacks from small bands of Forrest’s men attempting to delay their advance. While the bluecoats struggled on, Forrest concentrated his troopers at West Point, just south of the enemy.

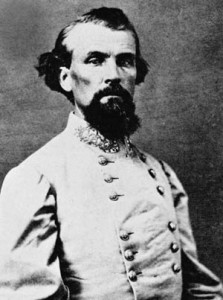

The Federals reached Okolona on the 18th and commenced razing the land and tearing up track from the Mobile & Ohio at a leisurely pace. Smith’s tardiness may have stemmed from a desire to abort the mission altogether because of the presence of Forrest. (The day before, he had broached this idea to his officers, citing the gathering of enemy forces at West Point and the fact that they were already eight days late in joining Sherman at Meridian.) A skirmish on the 19th left Forrest determined to try to channel the enemy between the swollen Tombigbee River on the right and the overflowing Sakatonchee River 12 miles to the west. Meanwhile, after reaching West Point on the 20th, Smith said he was too ill to continue and turned over command to Brig. Gen. Benjamin Grierson, but not before he ordered Grierson to abandon all plans to meet Sherman at Meridian. When Grierson insisted that he would press on to Meridian, Smith reassumed command and immediately ordered a countermarch to Memphis. According to an officer in the 4th U.S. Regular Cavalry Regiment, “Our General Smith was a beaten man well before Forrest ever delivered a blow against him.”

As the Federals headed north on the 20th, a spirited clash occurred between their rear guard and Forrest’s main body. After a two-hour contest, the Federals failed to dislodge the Confederates, who were firing from behind a log and rail fence, and drew off to the north. For the rest of the day, the Rebs pushed after the enemy, not stopping until they reached the outskirts of Okolona. At Egypt Station on the 21st, a Confederate assault led by Forrest himself forced the Federals through Okolona to a small rise west of town. Forrest ordered a saber charge by Colonel Tyree Bell’s brigade that shattered the 7th Indiana Cavalry Regiment and routed the remainder of its parent 3rd Cavalry Brigade on the road to Pontotoc. Forrest led the chase after the defeated enemy, but halted after five miles to give his disordered command time to regroup.

As the enemy pursuit slackened, Smith established a defensive line on a ridge atop Ivey Farms. Protected on both flanks by steep ridges and in front by thick underbrush and patches of oak trees, Smith’s position was the best defensive terrain he had occupied since leaving West Point. Most of the men were dismounted, and a battery of four cannon supported them. An attack on foot by the Confederates was repulsed, and Colonel Jeffrey Forrest, younger brother of General Forrest, was killed. With a mixture of rage and despair over his sibling’s death, Forrest led a second assault on the enemy lines. The blow was delivered just as the Union cavalry was mounting up to continue its retreat. The fight moved on for two miles to another improvised Union position, from which they were pried out of by the following graycoats. During the fighting Forrest had two horses shot from under him.

A mile up the road, the Federals made a last stand. Over 2,000 blue cavalrymen faced off against Forrest’s 300-man vanguard, the only Confederates who were able to keep up with the rapid Union retreat. Seeing the miniscule Rebel force facing them, the Northern troopers attacked. The Confederates counterattacked, and a wild melee ensued. With the odds heavily against him, Forrest was on the verge of being overwhelmed when the brigades of Bell and Colonel Robert “Black Bob” McCulloch arrived in time to strike the enemy flanks and send them reeling toward the rear. Almost out of ammunition and exhausted after two days of combat, Forrest called off any further pursuit.

“That Devil Forrest”

For all intents and purposes, the Union cavalry was a beaten force. Reaching Pontotoc on the night of the 21st, the command was thankful “that Devil Forrest” was no longer barking at their heels. According to Colonel George E. Waring of Smith’s command, “The retreat to Memphis was a weary, disheartening and almost panic-stricken flight, in the greatest disorder and confusion.” For the next week, elements of Smith’s riders straggled back into Memphis, completely spent. In the running fight from West Point to Okolona, Smith had lost 47 killed, 152 wounded, and 120 missing. Forrest’s losses amounted to 27 killed, 97 wounded, and 20 missing in action.

While Smith’s cavalrymen were being driven back to Memphis, Sherman’s infantry columns steadily marched for Vicksburg. In parallel lines, Hurlbut’s and McPherson’s men passed Decatur, then Union, while Winslow’s horse brigade headed for Canton, 25 miles north of Jackson. On the 26th, the Union infantry corps passed over the Pearl River and entered Canton, destroying the town of 2,500 citizens and the rail lines surrounding it. On February 27, Sherman left his army and went to Vicksburg to discuss a planned joint operation on the Red River with Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks.

On March 1, in wet, freezing weather, Hurlbut’s and McPherson’s weary foot soldiers left Canton for Vicksburg, reaching their old camp grounds on the Black River east of the city on the 3rd. The entire march from Canton to the Big Black had been monitored by Lee’s cavalry, which had set numerous ambushes for the infantry and the army’s supply trains. Despite their best efforts, the Southern horsemen could make no headway against the massed, compact enemy formations.

Meanwhile, Polk had received some much-needed reinforcements in the form of Lt. Gen. William Hardee’s 10,000-man infantry corps, and was eager to throw them at the retreating enemy. However, the reinforcements had arrived at Demopolis on February 27, long after Sherman’s army was out of harm’s way.

A New Policy of “Hard War”

In the end, Sherman’s Meridian expedition was at most a limited and fleeting success. Considering the numbers of troops involved, there was no large-scale infantry combat. In fact, most of the fighting was done by mounted forces. Losses were small considering the number of troops involved. Hurlbut and McPherson lost 126 men, while Winslow sustained 70 casualties. The Confederates lost 359 men, including those from Forrest’s command. Sherman had wanted to cripple the Rebel forces in Mississippi, thus removing any threat to Vicksburg or of reinforcements being used in other theaters of the war. On both counts he failed. For the remainder of the conflict, Confederate bands would harass Federal lines of communication and tie down large numbers of Union troops in Mississippi, Georgia, and Tennessee, while the transit of Southern forces to Georgia from the Magnolia State was never seriously interrupted.

Sherman’s second aim, the destruction of the natural resources and infrastructure of Mississippi, was also minimally successful. Despite the elimination of 59 miles of rail track and the destruction of 21 locomotives, 45 railroad cars, and miles of telegraph wire, the Confederates were able to replace most of these losses in a matter of weeks. The devastation of the land and its farm produce created hardships for the local population but never seriously impeded the operations of the South’s western armies in the last year of the war.

But whatever level of success could be attributed to Sherman’s Meridian enterprise, one thing was certain: it heralded the start of a new Federal policy of “hard war” designed to beat down the Confederacy by not only eradicating its armed forces but also degrading Southern morale and undermining its economy. In that sense, Meridian was a dress rehearsal for the merciless struggle Sherman would later perfect in Georgia and the Carolinas.

Good description of the battle and wby the civil war went on so long.

Love your analysis- do you have a source for sherman quote on on hell southerners deserved

I am registered but can not get in this issue but the 3 succeeding issues. I have complained about this problem. previously, but it seems like nobody has an answer. I have been a subscriber of WWII History for many years if that counts for something

Sorry you are continuing to have problems. We have replied to your comments via e-mail on several occasions, including today, March 13, Feb. 25, and Feb. 24, and you responded to us on Feb. 25. If you are not receiving some of our e-mails perhaps check your e-mail spam folder.