By Mike Phifer

Peering through a pair of field glasses, Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest perched in an oak tree on Missionary Ridge, overlooking the Tennessee town of Chattanooga, and observed a Union army in complete disarray. The day before, September 20, 1863, the Confederate Army of Tennessee had smashed the Army of the Cumberland after two days of bloody fighting at Chickamauga, GA., 10 miles due south of Chattanooga. The Yankees were falling back on Chattanooga. From what Forrest could see, the bluecoats were abandoning the town in a headlong rush.

Climbing down from the tree, Forrest dispatched a message to his superiors, recommending that they press the enemy as soon as possible. Despite Forrest’s urging, the Confederate commander, General Braxton Bragg, did little. A second message from Forrest indicating that the Federals were fortifying their position and time was at the essence to strike them did not stir Bragg into action either. With over 18,400 casualties from the two-day battle of Chickamauga, Bragg was in no hurry to pursue the Federals. Eventually he did order troops toward Chattanooga later in the day, only to discover that Forrest been right—the Federals were fortifying Chattanooga. “What does he fight battles for?” the ever-aggressive Forrest wondered aloud.

Nestled in southeastern Tennessee astride the border with Georgia, Chattanooga was surrounded by rugged mountains and ridges. Dominating the town on the east was Missionary Ridge. Southwest loomed Lookout Mountain. West of town and two miles beyond Lookout Mountain lay Raccoon Mountain. North of town was Walden’s Ridge, which ran northeastward for 40 miles. Curving around Chattanooga on three sides was the turbulent Tennessee River, which jutted south, then swung north, creating a peninsula called Moccasin Point, and sped through the deep gorges between Raccoon Mountain and Walden’s Ridge, eventually passing the Union supply depot at Bridgeport, AL.

At the start of the Civil War, Chattanooga was a comparatively young town, founded less than three decades earlier, but it had risen to a position of primary importance for the South as a key railroad hub in the western theater of the war. Railway lines connected directly or indirectly with Nashville, Charleston, Atlanta, and Richmond. By controlling the rail lines and hampering the South’s movement of supplies, the North could use them to move their own supplies to Chattanooga and use the town as a base of operations for a push into Georgia.

Although shaken over his bloody defeat at Chickamauga, where his army had suffered over 16,000 casualties, Union Maj. Gen. William Starke Rosecrans was determined to hold on to Chattanooga. Fearing large Confederate reinforcements that were rumored to be coming, Rosecrans pulled his army into Chattanooga proper, giving up vital strategic positions such as Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge. The Federal troops quickly began to dig in and fortify a three-mile-wide semicircle around Chattanooga in preparation for either a lengthy siege or a sudden attack.

The Confederates occupied the high ground as they began to set up a siege line around Chattanooga. With roughly 46,000 men, Bragg spread his army in a seven-mile semicircle. The Confederate left was anchored at the foot of Lookout Mountain, running eastward to Missionary Ridge. From there it progressed north to Chickamauga Creek, located about two miles from the point where the creek flowed into the Tennessee River. Roughly a mile of open farmland separated the two armies.

The left flank of the Confederate position was under the command of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, temporarily assigned to Bragg with his I Corps from the redoubtable Army of Northern Virginia. Longstreet, whose eleventh-hour arrival at Chattanooga had led to the stunning Confederate breakthrough on the morning of the 20th, was ordered by Bragg to put guns on top of Lookout Mountain and bombard the Federals. It took three long, backbreaking nights for mule teams to drag Colonel Edward Porter Alexander guns up the mountainside to avoid enemy artillery fire from Moccasin Point. Once at the summit, Alexander moved 20 guns up beside Captain James Garrity’s two Parrot guns, which were already on the mountain. On September 29 the guns opened up for the first time, but they would prove to have little effect.

If Confederate artillery fire was ineffective, their near-total control of Union supplies lines was much more so. It was not long before the Federal troops were beginning to have their rations cut. Getting supplies into Chattanooga was by no means easy. They had been coming in from Nashville by rail to Stevenson, AL., then northeast, pass Bridgeport and across the Tennessee River on to the junction at Wauhatchie, and finally into Chattanooga. With the two railroad bridges across the Tennessee River and Chickamauga Creek destroyed, and with Lookout Mountain in Confederate hands, which this route was no longer useable. A wagon road running beside the tracks was cut off as well.

Travel on the Tennessee River was hampered by a summer drought, as well the treacherous parts of the river and Rebel presence along one bank. A fourth route into town, by road led from Bridgeport to a small place called Prigmore’s Store. From there, Haley’s Trace was taken to the Tennessee River, where the trace followed the north bank of the river for a few miles before joining the Anderson Road, which led to Chattanooga down Signal Mountain. This route was cut on October 8, when the 4th Alabama Regiment from Brig. Gen. Evander Law’s brigade of Longstreet’s corps shot down the mules in the Union wagon trains moving along the road.

This left only one other route for Rosecrans’ hungry men to get even a meager amount of supplies. It originated from Bridgeport and moved past Prigmore’s Store farther up the Sequatchie Valley until it reached Anderson Road. It then followed this road over the rugged Walden’s Ridge, where water and forage proved to be scarce. Intermittent heavy rains made the route even more difficult. For the hungry Federals at Chattanooga, the supply situation was critical—and about to get worse.

With 4,000 troopers, Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, commander of the Army of Tennessee’s cavalry, forded the Tennessee River 30 miles above Chattanooga on October 1 with orders to strike the Federal supply line. He did this on October 3, when Wheeler’s command plundered and torched a large Federal supply train stretching for five miles up Walden’s Ridge. Another part of Wheeler’s command sacked the enemy garrison at nearby McMinnville. There, Wheeler’s force reunited, and for the next few days they rode deeper into Tennessee, stirring up trouble as they went. With Federal cavalry closing in on them, Wheeler’s troopers fought running battles, shucking their loot as they attempted to escape back to Confederate lines. On October 7, Wheeler stopped to fight the Yankee cavalry at Farmington and was defeated. Suffering heavy casualties, the weary Confederate troopers then slipped back over the Tennessee River, disorganized and in bad shape.

Wheeler’s raid made a bad situation worse for the Union troops in Chattanooga. “This is starvation camp,” complained one Federal soldier as the food shortage in Chattanooga became critical. Rations dropped to half-rations, and some troops got even less. Forage and feed was also scarce for the horses and mules, and some soldiers even took the desperate initiative of stealing grain from the animals or picking fallen pieces out of the mud. One Kansas soldier watched with extreme distaste as his comrades caught and ate a dog that wandered unsuspectingly into camp. An Indiana private paid his own brother-in-law $14 for 14 crackers, and a cow’s tail went for $10 on the open market.

The lack of provisions also prevented Union reinforcements, consisting of the XI and XII Corps from the Army of the Potomac under the command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, from moving into Chattanooga. As things stood, they would only be more hungry mouths to feed. Instead of moving into Chattanooga, XII Corps was strung out along the railroad leading into Bridgeport to guard it against further cavalry depredations by Wheeler. The rest of Hooker’s troops waited near Bridgeport.

Conditions were little better for the besieging Confederates. “The soldiers were starved and almost naked, and covered all over with lice and camp itch, filth and dirt,” wrote Confederate private Sam Watkins, who lived through the siege. Food supplies were readily available, but Bragg hoarded them at Chickamauga Station for future use. Besides being poorly fed, the Confederates were mostly bivouacked in open air, with little shelter from the heavy rains and early-autumn cold. Life for the men was miserable and many of them were sick with colds and flu. Like the Yankees’ horses and mules, the Rebels’ own livestock suffered terribly from a lack of forage.

Hunger was not only problem plaguing the Confederate army. Braxton Bragg was not a popular commander, to say the least, and there had been frequent contention between him and his subordinates for some time now. With a major, if inconclusive, victory under his belt after Chickamauga, the petty and vindictive Bragg turned his attention to purging his worst critics within the army. The first to go were Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk and Maj. Gen. Thomas Hindman. Bragg, however, was not the only one on the offensive. A petition was circulated among the senior generals of the army asking Confederate President Jefferson Davis to remove Bragg. The generals, as spelled out in the petition, were concerned that any gains made at Chickamauga were in danger of being thrown away. The army, they said, had unwisely been forced on the defensive “and may deem itself fortunate if it escapes from its present position without disaster.” Twelve generals signed the extraordinary document, including corps commanders Longstreet, Lt. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill and Maj. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner.

Davis, one of Bragg’s few personal friends, quickly waded into the feud, arriving at Bragg’s headquarters on October 9. A formal meeting was held where Davis, with Bragg in red-faced attendance, heard from the four corps commanders. (Major General Benjamin Franklin Cheatham had temporarily taken over Polk’s corps.) The president asked the corps commanders to give their opinion of Bragg openly and to his face. It was none too favorable. Bragg endured the public embarrassment, knowing that he would not be replaced—Davis had already promised him that he would retain his command.

With his position secure, Bragg turned his full ire on the conspirators. With Davis’s intervention, charges were dropped against Polk, but he was transferred to another department. D.H. Hill was suspended and Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge was given command of this corps. Next in line came Buckner, who besides commanding a corps also commanded the Department of East Tennessee. Davis, at Bragg’s request, disbanded that department, leaving Buckner with only a division to command. Longstreet survived Bragg’s wrath, but in the coming days the feud would intensify between the two, with dire consequences for the Army of Tennessee.

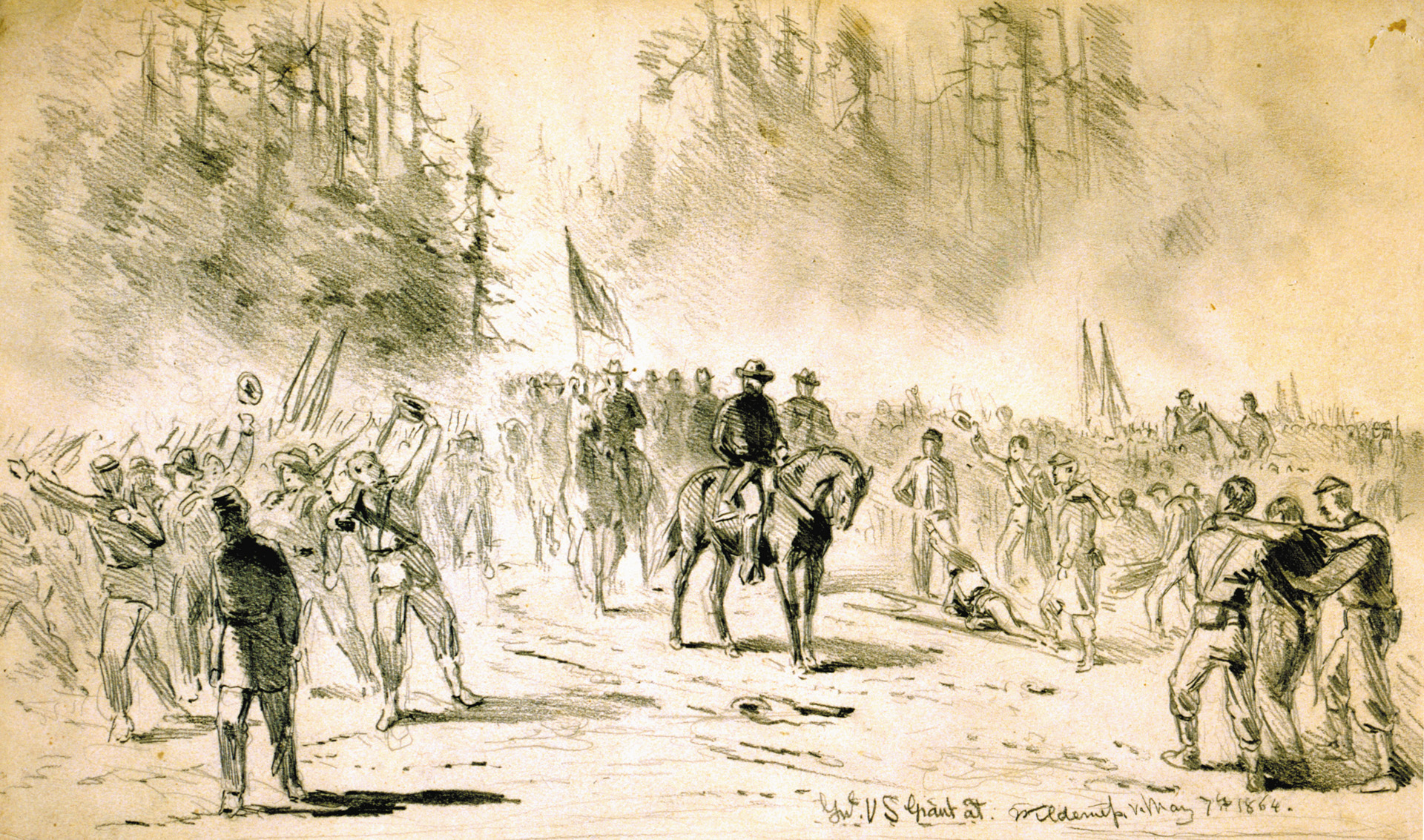

Meanwhile, great changes were about to take place in the Union camp. Aboard a train headed for Louisville, KY., Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in a secret meeting with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, was given command of the newly created Military Division of the Mississippi, which encompassed the Armies of the Cumberland, the Ohio and the Tennessee. As the commander of the new Military Division, Grant was given power to decide who would command the Army of the Cumberland. Stanton’s assistant in Chattanooga, Charles Dana, had been sending a stream of unflattering telegraphs to Washington, warning falsely that Rosecrans’s was preparing to abandon the city. Abraham Lincoln, irritated and perplexed by Rosecrans’ supposed actions, observed ruefully that ever since Chickamauga the general had been acting “confused and stunned, like a duck hit on the head.” Grant, equally bemused, tersely telegraphed Rosecrans, informing him that he was relieved of command and appointing his erstwhile second-in-command, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, as the army’s new head. Grant sent a second telegram to Thomas, ordering him to “hold Chattanooga at all hazards.” “I will hold the town until we starve,” Thomas wrote back.

Arriving at Bridgeport by rail, Grant, despite a bad leg suffered in a recent fall off his horse, mounted up and rode through the pelting rain over Walden’s Ridge. As darkness was setting in on October 23, Grant and his staff arrived at Chattanooga, heading straight for Thomas’s headquarters. After hearing a baleful description of the conditions inside the city, Grant listened to a plan outlined by his chief engineer, Brig. Gen. William “Baldy” Smith, to open a new supply line from Bridgeport to Chattanooga. After crossing a pontoon bridge from Chattanooga, a road cut west across Moccasin Point to Brown’s Ferry. On the other side of the Tennessee River, the road cut through a gorge in the foothills overlooking the river and proceeded south to the small settlement of Wauhatchie, where it split onto another road and passed west through Lookout Valley to Kelley’s Ferry. There the road led to Union forces at Bridgeport. If the Rebels could be forced from their position at Brown’s Ferry and the surrounding area, this key supply route could be opened up. The following day, after seeing Brown’s Ferry himself, Grant authorized Thomas and Smith to implement the plan.

In the early morning of October 27, 1,400 men from Brig. Gen. c’s brigade boarded 50 specially constructed pontoon boats and two flatboats and slipped silently down the rive to make a surprise attack on Brown’s Ferry. A light fog helped shroud the flotilla as it rowed seven miles through enemy territory. Confederate pickets could be spotted warming themselves by campfires, but no one observed the makeshift flotilla. Eventually, a signal fire near Brown’s Ferry on the Union side of the river was spotted, and the flotilla pulled hard for the Rebel side. Suddenly rifle fire opened up from a handful of Confederate pickets. With all surprise gone, the Federals rushed ashore and drove off the pickets, seizing the two key hills. Meanwhile, the pontoon boats rowed to the east bank of the river, where the rest of Hazen’s command, 750 men under the command of Lieutenant Colonel E. Bassett Langdon, waited to cross over. With them were another 3,500 men from Brig. Gen. John Turchin’s brigade, who made up the second force in Smith’s plan.

While the advance party quickly fell to cutting down trees to built breastworks on the hills they held, the Confederates were on their way to dispute the landing. Colonel William Oates of the 15th Alabama led six companies of his men into the darkness and fog toward the ferry. The men, part of Law’s brigade, were soon joined by the 4th Alabama of the same brigade. The Federals were driven out of their position and back toward the river, where Langdon’s men, who had just crossed over the river, reinforced them. Now outnumbered and with Oates wounded, the Confederates fell back toward Lookout Mountain. With their bridgehead secure, the Federals quickly threw a pontoon bridge across the Tennessee River to hurry across reinforcements.

While the Federals secured Brown’s Ferry, Hooker was on the move from Bridgeport with the XI and XII Corps to join them. After a rugged march along the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, Hooker’s men camped at Whiteside, a small railroad station about 10 miles from Brown’s Ferry. Longstreet was not greatly alarmed by the capture of Brown’s Ferry. In his mind it was only a feint; the real threat was about 20 miles southwest of Lookout Mountain, where scouts had reported seeing large numbers bluecoats on the march from Shellmound. Bragg, on the other hand was greatly disturbed by the loss of Brown’s Ferry and ordered an immediate counterattack. Longstreet did nothing all day, but toward evening he did inform Bragg where he believed the real Federal threat was. The following day, October 28, Bragg rode over to see Longstreet, where he found him on the summit of Lookout Mountain. Fiery words were exchanged between the two over Longstreet’s inaction, but the conference was cut short when word reached them that a large Federal column was marching through Lookout Valley toward Brown’s Ferry.

The column was Hooker’s two corps. Ineffective Confederate artillery fire greeted the Union troops as they marched into the valley. After easily brushing aside the 6th South Carolina Regiment, Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s men, in the lead, marched past Wauhatchie and joined up with Hazen’s troops at Brown’s Ferry around 5 pm About hour behind Howard was Maj. Gen. John Geary’s division, which made camp at Wauhatchie for the night. Longstreet was again ordered by Bragg to attack the Federals at Brown’s Ferry, but he decided to hit the isolated Geary instead. Rugged terrain slowed Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins’ command as it moved through the darkness, some brigades not reaching their assigned position until nearly midnight. Concerned over the reinforced Federals at Brown’s Ferry, Longstreet and Jenkins weakened their original plan by sending only one brigade, under Colonel John Bratton, to engage the enemy. Two other brigades were sent to reinforce Law’s brigade, which was posted on a hill between Lookout Creek and Brown’s Ferry to block any Federal reinforcements..

Driving in the Federal pickets, Bratton attacked the Federal encampment, which was now busy extinguishing their campfires and forming up. Four guns from Knap’s Pennsylvania Light Artillery, positioned on a slight hill 50 yards behind the Union lines, opened up on the advancing Rebels. A wild firefight flashed through the darkness, each side shooting at the enemy’s muzzle blasts. “Pick out the artillerists,” came a shout from the attacking Confederate troops. Almost half the artillerymen were picked off along with the bulk of the artillery horses.

While the firefight blazed away, Bratton sent the Palmetto Sharpshooters to flank the Union right. Hampton’s Legion, meanwhile, had orders to find the Federals’ left flank. Wading through a swamp with some reluctance, Hampton’s Legion moved out of a gully and hit the Federal wagon train, driving off the teamsters. Frightened mules stampeded and caused confusion for both sides as they bolted for freedom. The 137th New York quickly arrived on the scene and managed to force Hampton’s Legion back into the swamp.

On the Federal right, the Palmetto Sharpshooters took cover along a railroad embankment and opened up on the 111th Pennsylvania’s’ exposed flank. The Pennsylvanian refused their left with two companies, but they would need reinforcement’s if the Rebels decided to assault them. Colonel William Rickards Jr., seeing this threat, ordered the artillery commander to take one of his remaining two guns to a position on the railroad embankment and blast the Rebel sharpshooters in their flank. Not having enough horses to pull the guns, Rickards ordered two companies of the 29th Pennsylvania to wheel them into in position. The gun soon drove off the Palmetto Sharpshooters, who with the 6th South Carolina who were getting ready to charge. Bratton pulled back his brigade after receiving word that Federal reinforcements were on the way.

Hooker was alarmed at the sound of artillery fire coming Geary’s encampment. Wasting no time, he ordered Howard to send help. Howard in turn ordered two divisions, under the command of Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz and Brig. Gen. Adolph von Steinwehr, to move out. Not far out of camp, the Federals came under fire from Law’s men, who were dug in on timbered ground overlooking the Brown’s Ferry-Wauhatchie Road. Hooker, fearing Rebel intentions, ordered them attacked. For two hours, Law’s men held off the Federals before being driven from their hill. It was 7 am before the first Federal troops reached Geary.

The new supply line, immediately dubbed “the cracker line” by delighted bluecoats, was now open; Lookout Valley was firmly in Federal hands. Besides much-needed food supplies, reinforcements were also on the move to Chattanooga. After Rosecrans’ Chickamauga defeat, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman had been ordered north from Mississippi to come to his aid. Sherman’s advance had been slowed by the need to repair railroads along the way. On October 27, Grant ordered Sherman to leave the railroad repair to others and hie his Army of the Tennessee to Chattanooga as fast as he could.

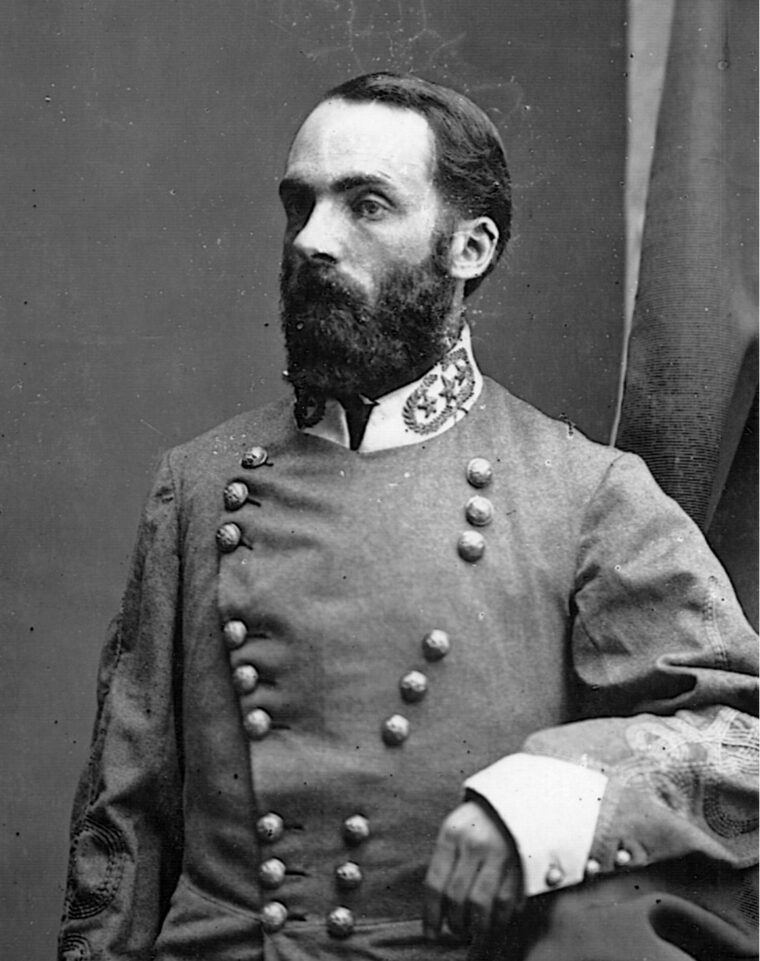

While the Federal forces was growing to over 60,000 men, Bragg unadvisedly weakened his own forces on November 4 by ordering Longstreet’s corps, along with Wheeler’s cavalry, to move north against Knoxville, TN., drive off Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside and hopefully force Grant to weaken his position at Chattanooga by sending aid in that direction. With the loss of Longstreet, whom Bragg was glad to get rid of, the Army of Tennessee, consisting of two corps, now numbered around 35,000 men. Lieutenant General William Hardee, who returned in late October, commanded Polk’s former corps, while the other was commanded by Breckinridge.

With Longstreet on the move against Burnside, Grant was pressured by Washington to do something to aid his fellow general. Grant believed an attack against Bragg would force a recall of Longstreet. On November 7, he ordered Thomas’s army to attack the north end of Missionary Ridge and threaten the Rebel line of communication between Dalton, GA., and Cleveland, TN. Thomas was shocked by the order, as was Smith, an old friend of Grant’s from West Point days who managed to get his former classmate to countermand the hasty order. Grant wisely decided to do nothing until Sherman arrived.

Late in the afternoon of November 14, Sherman arrived at Grant’s headquarters in advance of his army and received his orders. Once Sherman got his army over Brown’s Ferry and through the hills north of Chattanooga, he was to conceal his force in the woods along the Tennessee River, across from the mouth of Chickamauga Creek. Under the cover of darkness he was to cross the river and hit the north end of Missionary Ridge at Tunnel Hill and roll up the Confederate right. Next, Sherman was to move onto Chickamauga Station in an attempt to get in the rear of Bragg’s army and cut off his retreat.

Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland was to play merely a supporting role, holding the center of the Federal line. Once Sherman had smashed the Confederate right, Thomas was to advance up Missionary Ridge and link up with Sherman. Hooker, meanwhile, was to threaten the Confederates on Lookout Mountain. The attack was scheduled for November 21.

The timing would prove to be overly optimistic. Bad weather plagued Sherman’s troops, who began leaving Bridgeport on November 17. Muddy roads, high water, and a smashed pontoon bridge slowed their advance, causing the attack to be postponed. Thomas, worried about Sherman’s delay, urged Grant to have Hooker attack Lookout Mountain in the meantime, thereby threatening the Confederate left flank. Grant, not totally trusting Hooker, said no.

On the night of November 22, Confederate deserters brought word that Bragg was retreating. A couple of days earlier, Grant had received a puzzling note from Bragg advising him to remove all noncombatants from Chattanooga. Grant wondered if Bragg wanted him to believe an attack was imminent while his real intention was to retreat. The last thing Grant wanted Bragg to do was pull out now—he was confident that once Sherman was in position, the Confederates would be trounced. In actuality, Bragg wasn’t retreating after all. Instead, he had merely dispatched Irish-born Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne, another of his critics, to take his division to Chickamauga Station to catch the rails and reinforce Longstreet.

Early on November 23, Grant ordered Thomas to find what Bragg was doing. Thomas in turned ordered Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood’s division to make a reconnaissance in force toward Orchard Knob, a 100-foot-high elevation that was held by Confederate pickets midway between the Federal line and Missionary Ridge. To the right of Wood, Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s division was to play a supporting role in case of a Rebel counterattack. Howard’s XI Corps took up position on Wood’s left. With flags flying, the drums beating and bugles sounding, almost 25,000 Union soldiers wheeled into line. It was an impressive sight, awing the Confederate pickets and civilian onlookers.

At 1:30 pm, Wood and Sheridan moved forward. Wood’s men captured the knob and began reversing the Confederate breastworks. The outnumbered 24th Alabama put up minimal resistance before wisely withdrawing up Missionary Ridge. The 28th Alabama, on the other hand, held their position, stalling Hazen’s brigade. Eventually, however, the Federals overran the position and captured the regimental colors in the process. Instead of withdrawing after making his reconnaissance, Wood received orders to dig in. Sheridan began constructing breastworks on Wood’s right. Howard’s men, who began their advance two hours after Wood’s, ran into trouble. Their attack was stopped cold by the Confederates, causing Wood to send one of his brigades to their assistance. There was no question now that Bragg was staying put.

If the attack confirmed in Grant’s mind that the Rebels were not retreating, it also indicated to Bragg that the Yankees were concentrating on his weak right flank. He quickly took measures to remedy this by recalling Cleburne from Chickamauga Station. Bragg also recalled Kentucky troops guarding the station as well and began shifting units from Lookout Mountain. Hardee was ordered to take command of the Confederate’s right flank. Breckinridge held the center, while Maj. Gen. Carter Stevenson was to command atop Lookout Mountain.

While the Federals were digging in on Orchard Knob, Sherman’s army began to move out for the woods along the Tennessee River in preparation for a crossing sometime after midnight. Two regiments in 116 pontoon boats, moved out from North Chickamauga Creek and down the river landing on the Rebel side, where they quickly captured the enemy pickets. With the east side of the crossing secured, troops began being ferried over at 1:30 am. Fiver hours later, two divisions were across. While this was going on, engineers were busy constructing a pontoon bridge across the river.

Once his three divisions were across the river, Sherman moved out at around 1:30 pm to seize Tunnel Hill, at the north end of Missionary Ridge. A railroad tunnel underneath the hill had given it the name. An hour later, Cleburne arrived on the scene and was met by Major D.H. Poole, a staff officer of General Hardee’s who directed him where he was to deploy his men. Before Cleburne had taken up position, word reached him that the Yankees were coming up the far side of a detached hill northeast of the ridge. Cleburne’s immediately sent a brigade of Texans under Brig. Gen. James Smith to capture the hill first. They were too late. Driven back by Sherman’s troops, the Texans quickly redeployed on Missionary Ridge proper and easily repulsed a weak enemy assault. While they held off the bluecoats, Cleburne positioned the rest of his division carefully behind large rocks and thick trees. Any chance Sherman had of quickly seizing the Confederate right was gone.

Due to bad maps and poor reconnaissance, Sherman had misread the lay of the land. The detached hill his men captured, he believed wrongly, was Tunnel Hill. Instead of making a general assault after discovering his mistake, Sherman had his men dig in and they would attack the next day. As darkness fell, Cleburne prepared to withdraw believing the order would be given as disaster had befallen the Confederate left flank.

While Sherman’s troops were crossing the Tennessee River on the morning of November 24, Hooker was preparing to take Lookout Mountain. Originally he was only to “make a demonstration” against the mountain, but after the pontoon bridge broke at Brown’s Ferry, trapping Brig. Gen. Peter Osterhaus’s division in Lookout Valley, Hooker’s orders were changed. With the addition of Osterhaus’s troops, Hooker now had three full divisions, numbering around 10,000 troops, at his disposal, Grant cautiously gave him permission to take the mountain if it proved practical.

Geary’s division moved out around 8 am in a heavy fog, alongside a brigade from Brig. Gen. Charles Cruft’s division of the Army of the Cumberland. They overran and captured 40 Confederate pickets and crossed Lookout Creek. Geary’s formed his men into three lines, with skirmishers out ahead. With his left flank along the creek and his right stretching all the way to the steep mountain wall, Geary sent his bluecoats forward along the side of the mountain, climbing over boulders and through heavy timber.

To defend the mountain and left flank of the Confederate line, Stevenson had six brigades, two of which he had dispatched into the valley to plug the gap left by Bragg in shifting more troops over onto Missionary Ridge. Two brigades were kept on top of the mountain, the remaining two were posted half down the promontory. A little less than half of Brig. Gen. Edward Walthall’s brigade stretched out as pickets and skirmishers from Lookout Creek to the palisades. The other half of his brigade Walthall positioned about 500 yards from the Cravens house, a local landmark that was located on a plateau just below the mountain summit. It was here that the bulk of Brig. Gen. John Moore’s brigade was posted.

Spotting the Federals coming, Walthall formed his men up behind crude breastworks and prepared to meet the enemy. Unfortunately for them, the breastworks were designed to defend from an attack from below, while the Federals were coming from the side. With flags waving, the Federals mounted a bayonet charge that overran the Southern position and scooped up many prisoners. Supporting Union artillery fire intensified as the Confederates attempted to escape up the mountain. Walthall was in desperate need of help, but he would find little from his immediate superior, Brig. Gen. John Jackson, who remained in the rear for most of the fighting.

By 11:30 am, Geary’s 2nd Brigade, commanded by Colonel George Cobham, and the 3rd Brigade, commanded by Colonel David Ireland, stalled when they came into contact with the remainder Walthall’s brigade near Cravens house. Taking enemy fire from farther up the mountain, the Federals charged Walthall again through a heavy fog, and broke the outnumbered Rebels, forcing the survivors back around the point of the mountain to Craven’s farm. Ireland’s and Cobham’s brigades were quick on their heels, overrunning two abandoned guns.

While Geary’s men pushed toward the farm, a second Union force began it advance. Colonel William Grose, leading the other brigade of Cruft’s division along with Osterhaus’s division, captured a bridge over Lookout Creek. Pushing back the Rebels, the Federals started up the mountain toward Lookout Point, capturing most of the small force facing them. Meanwhile, Moore moved his brigade toward the breastworks near Cravens house, at the edge of the plateau. They had not gone far when they ran into Walthall’s broken men, with the pursuing Yankees not far behind. It was nearly 1 pm when both sides let loose a terrific volley at each other through the fog. The Federals fell back, but only briefly. Fearful of being outflanked and outnumbered, Moore fell back near the Summertown Road. Walthall’s formed the remnants of his brigade on Moore’s left. Help was desperately needed.

“Tell Cleburne we are to Fight, That His Division Will Undoubtedly be Heavily Attacked, and That He Must do His Best”

Brigadier General Edmund Pettus’s brigade arrived just in time from the top of the mountain to reinforce the Confederate line. Fighting raged until after dark, but the Confederate line held. Hooker seemed content to hold what his troops had captured, but Bragg around 2:30 pm informed Stevenson that no relief would be coming and that he was to withdraw from the mountain once nightfall masked his moves. During the night the Confederates conceded Lookout Mountain to the Federals, and the dispirited troops were shifted over to the Missionary Ridge.

With the loss of Lookout Mountain and a strong threat to both of his flanks, Bragg was in a quandary as to his next move. Meeting with corps commanders at his headquarters, he uncharacteristically sought their advice. Hardee was for falling back past South Chickamauga Creek and, if necessary, deeper into Georgia. Breckinridge believed that Missionary Ridge still could be held. Bragg agreed. “Tell Cleburne we are to fight, that his division will undoubtedly be heavily attacked, and that he must do his best,” Hardee informed the Irishman’s assistant adjutant general. With no retreat in order, Cleburne recalled his artillery and positioned his 4,000 men to repel Sherman’s next assault, which was expected to come in the morning.

Grant intended for Thomas’s army to play only a supporting role on the 25th by capturing the Confederate rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge and threatening the main Rebel position. After the Stars and Stripes were seen atop Lookout Mountain that morning, Grant expanded Hooker’s role and told him to move down into Chattanooga Valley and push for Rossville Gap, where the enemy’s left flank was anchored. Grant still pinned most of his hopes on Sherman’s ability to roll up the Rebel right.

Despite some skirmishing, Sherman’s general assault against Tunnel Hill didn’t commence until around 10:30 am and was undertaken by two brigades from his brother-in-law Brig. Gen. Hugh Ewing’s division. Brigadier General John Corse’s brigade drove in the Confederate pickets and, enduring stiff artillery fire, pushed to with 50 yards of the Cleburne’s Texas brigade. The attack was thrown back, and the Texans counterattacked and drove the Federals back down the hill. A second Federal attacked was repulsed as well, and the bluecoats took cover and opened up on the Rebels, many concentrating on dropping Confederate artillerymen. Troops from the 7th Texas were sent to help man the guns, and the Federals who were forced back when Cleburne had two guns from another battery wheeled into action.

The other Federal brigade, under Colonel John Loomis, was stalled to the right of Corse by Confederate artillery fire. The Northerners were forced to take cover behind a railroad embankment far short of Tunnel Hill. A large gap now separated Loomis and Colonel Charles Walcutt, who had taken over for Corse after he was wounded. Threatening the gap and Loomis’s left flank were two Georgia regiments from Stevenson’s division. Two Pennsylvania regiments from Colonel Adolphus Bushbeck’s brigade were given the job of clearing the gap. This they did in style, forcing the Georgians back up Missionary Ridge and pushing their way up the western side of Tunnel Hill to within 30 yards of the summit.

Despite the progress, the Pennsylvanians did little to alleviate Loomis’s concern over his exposed left flank. Loomis sought assistance from Brig. Gen. John Smith’s division. Two of Smith’s brigades, under the command of Brig. Gen. Charles Matthies and Colonel Green Raum, were sent into the fray. Matthies’s men led the way, immediately coming under enemy artillery fire as they advanced toward Tunnel Hill. Matthies’s charge failed, as did Raum’s a short time later, but intense fighting continued to rage. One of Cleburne’s brigade commanders suggested they mount a bayonet charge instead of wasting ammunition. Cleburne gave the go-ahead.

Four regiments under Brig. Gen. Alfred Cummings launched the charge around 3:30 pm. The Confederate advance temporarily stalled as the troops had trouble getting through a narrow opening in their breastworks. Regrouping, the Confederates rushed into Matthies’s men, and after some brutal hand-to-hand fighting they forced them to retreat. Loomis and Walcutt, seeing the apparent hopelessness of the situation, fell back as well. Sherman, having suffered nearly 2,000 casualties, finally called a halt to the fighting. Outnumbered four-to-one, Cleburne had managed to hold the Confederate right. The situation on the left was not going nearly so well.

Observing the enemy positions on Missionary Ridge from Orchard Knob, Grant was convinced that Bragg was weakening his hold on the ridge to reinforce Cleburne. To aid Sherman’s faltering attacks, Grant ordered Thomas to move against the Rebel rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge. The Confederate position was not nearly as imposing it appeared. Bragg and Breckinridge had been lax in ordering breastworks constructed on the ridge. The poorly constructed breastworks that were built were placed on the top of the ridge, instead of the military crest a few yards below, which would have allowed the defenders a better field of fire down the slope. Half of Brig. Gen. Patton Anderson’s division (formerly Hindman’s) were posted in the rifle pits at the base of the ridge, as well troops from other brigades.

Six cannon shots from Federal batteries signaled the 23,000 Federal troops from the divisions of Brig. Gens. Thomas Wood, Richard Johnson and Abasalom Baird and Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan to begin the assault. The Federal officers were confused—were they supposd to take the rifle pits, or the ridge itself? Rebel artillery opened up on the Federals as they moved out into the open at 3:40 pm and began their advance. Shells screaming overhead, the Federals quickened their pace, some breaking into a run. Federal artillery fired in support of the blue wave sweeping across the 500 to 700 yards of open ground below the ridge. Most of the Confederates in the rifle pits let loose a single volley at the Federals and then, as ordered, retreated up the ridge. Those staying behind were either killed or captured.

As the Federals piled into the rifle pits trying to catch their breath, they soon discovered that they were vulnerable to fire from the ridge. “It was evident to everyone that to stay in this position would be certain destruction,” Brig. Gen. August Willich remembered. “The only place of safety was in the enemy works on the crest of the ridge.” After a brief delay, some of the junior officers, believing that their orders had been to take the ridge all along, urged their men forward. Others, sensing the trap they were in, spontaneously ordered their men up the ridge. Still others, veteran fighters with two years of bloody battles behind them, needed no orders to understand that they had either to go forward or die where they stood. Whatever the case, seemingly as one, the Army of the Cumberland began an incredible, fully unauthorized surge up Missionary Ridge.

As the bluecoats climbed out the rifle pits and began to advance up the ridge, Grant, watching from Orchard Knob, was appalled. He immediately demanded to know called for the assault. “Thomas, who called for those men up the ridge?” he demanded. Thomas said he did not know. Major General Gordon Granger, commander of the IV Corps, also denied any responsibility for the charge, but added excitedly, “When those fellows get started, all hell can’t stop them.”

Up the 400-foot-high ridge the Federals advanced in small, V-shaped clusters, following their regimental flags. Disorganized Confederates withdrew before them, stumbling backward over rocks and stumps. Their comrades on the summit held their fire, for fear of hitting their own men. At the foot of the ridge, ever-combative Phil Sheridan sportively lifted a silver whiskey flask to toast the Confederates watching from above. “Here’s to you!” he called. A Rebel cannonball landed nearby, spraying him with dirt and debris. “That’s damn ungenerous,” Sheridan cried. “I shall take those guns for that.”

Following close behind his troops, General Carlin shouted, “Boys, I don’t want you to stop until we reach the top of that hill!” Other Union officers challenged their men to race Carlin’s boys to the top. Bending over at the waist as they climbed the steep hillside, like men facing into a stiff breeze, the Federal troops moved ever upward. Closing in on the crest, the Federals lost formation as they struggled up the slope and through ravines that provided some cover from the Rebel fire. It was around 5 pm when troops from Wood’s division surged over the crest and caused a break in Confederate line. Simultaneously, the crest was carried in at least five other places. As more Federals broke through the enemy breastworks, capturing numerous enemy guns, the Confederate’s center position on the ridge became desperate. With any attempt for a serious counterattack hampered by the narrow ridge top, and with more and more Yankees pouring over the ridge, the Confederate center abruptly collapsed.

On the summit, Sheridan leaped astride the same cannon that had fired at him a few minutes before. Wrapping his stumpy legs around the barrel, the banty Irishman swung his hat and cheered. Brigadier General Charles Harker soon followed suit but made the mistake of choosing a recently fired gun, scorching his seat so badly that he could not sit on a horse for weeks. Everywhere, stunned Federals watched in amazement as their hated, eared, and grudgingly admired rivals simply ran away. “My God,” cried an Indiana private, “come and see them run!” Wood rode among his men, laughing, “Soldiers, you ought to be court-martialed, every man of you,” he joked. “I ordered you to take the rifle pits and you scaled the mountain.” Seven soldiers won Medals of Honor that day, including Lieutenant Arthur MacArthur, the father of future World War II general Douglas MacArthur. It was the most won in a single day in American history.

On Orchard Knob, Grant and the other generals watched, transfixe d. Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana, whose ceaseless vilification of Rosecrans had undermined that general’s authority and led directly to Grant’s arrival, was beside himself with joy. “Glory to God,” he wired Washington. “The day is decisively ours. Missionary Ridge has just been carried by a magnificent charge of Thomas’s troops.” Grant himself was considerably less sanguine. “Damn the battle” he was heard to say. “I had nothing to do with it.”

While Grant grumbled, the situation on the Confederate left was deteriorating. Breckinridge had rushed there just before the Federal assault on the army center. With only five regiments, Breckinridge could do little to stop Hooker’s three divisions from moving through the gap and heading north, rolling up Bragg’s left. Driven out of their positions and finally routed, Breckinridge yelled at his surviving troops, “Boys, get away the best you can.” With his men fleeing all around him, Bragg attempted personally to rally them. Instead all he got was the old army jeer, “Here’s your mule,” as the men pointedly ignored him.

The Confederate right, too, was in serious danger. Hardee immediately sent word to Cleburne to take his division, as well as the divisions commanded by Brig. Gen. States Rights Gist and Carter Stevenson and stop the Union advance. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Cheatham, positioned on Cleburne’s left, was attempting to do just that. In the growing darkness, two brigades from Cheatham’s division were pushed back by Baird’s troops, now only a mile from Tunnel Hill. Cheatham ordered in another brigade at 6 pm and halted the Union advance. Most of the other Federal divisions had halted as well, except for Sheridan, who pushed on through the darkness, bagging more prisoners and guns before finally halting his division at South Chickamauga Creek around 2 am.

Cleburne withdrew his division that night and the next day acted as the rear guard of the demoralized Army of Tennessee. After burning provisions hoarded at Chickamauga Station, the Confederates began a retreat for Dalton. Shortly after midnight,Bragg ordered Cleburne to proceed to Ringgold Gap to try to buy more time for the army and their wagon train to escape. Early on the morning of November 27, Cleburne arrived at the gap and positioned his division to defend the narrow opening in the ridge. For over four hours Cleburne successfully beat back Hooker. Shortly after noon, Bragg informed Cleburne that the wagons were safe and that he could withdraw. Grant ordered no further pursuit.

A few days after the battle, Braxton Bragg resigned as commander of the Army of Tennessee. Jefferson Davis accepted his resignation without comment. Tennessee was lost to the Confederates now, and the “Gateway to the South” was wide open for William Tecumseh Sherman to begin planning his campaign for Atlanta, a campaign that would spell even more disaster for the embattled Confederacy.

This article ought to have some maps and could use some editing for grammar and spelling.

Here is a recent story about Grant’s role at Chattanooga that includes a map you may find of interest:

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/a-spectacle-of-singular-magnificence/