By Arnold Franco

World War II, being far more fluid than World War I, marked the advent of the mobile radio intercept unit whose task was to pick up, decrypt if possible, and pinpoint enemy units sending their messages through the airways. The U.S. Navy set up intelligence teams on various carriers and command ships soon after the Battle of Midway. The British Army, followed by the U.S. Army, put together similar groups in the North African campaigns. They were called “Wireless Units” by the English, “Signal Radio Intelligence Companies” or “Signal Service Companies” by the U.S. Army, and “Mobile Radio Squadrons” by the U.S. Army Air Force.

In England, late in March 1944 while the English and American armies were feverishly preparing for the invasion of Normandy only two months away, the U.S. Ninth Air Force, whose assignment it was to conduct the tactical air war over the Continent, ordered a Major Harry Turkel to form and train a new unit in time for the invasion.

The new unit’s task was to monitor and intercept German Air Force radio traffic while operating out of mobile caravans designed to keep pace with advancing armies. This new unit was to be aptly named the 3rd Radio Squadron Mobile (“G,” for German).

In order to perform the nearly impossible in so short a time, Turkel was given extraordinary powers to co-opt men from any U.S. unit in the United Kingdom. His long arm even reached back to the States.

I was a product of this levy. In late April 1944 I was among 10 who had trained in German at Michigan State College and were then in a code-breaking class at Vint Hill Farms Station, Warrenton, Va. We were suddenly ordered to prepare to leave, within 24 hours, by plane for London to join the 3rd Radio Squadron Mobile (R.S.M.).

Voice-Intercept Operations on the D-Day Invasion

For Detachment “A,” the code-breakers, he was able to find two young and intelligent lieutenants, Mortimer Proctor, Jr. of Proctor, Vt. (son of the governor); and Hugh Davidson, a University of Chicago graduate. They were the only ones in the squadron with previous code-breaking experience, as civilians with the Signal Corps in Washington.

With experienced British officers as teachers, we received hands-on training with real-time German messages at various places throughout southern England. The British proved to be excellent instructors and apparently we were apt pupils. On The D-Day Invasion, a 20-man echelon of Detachment “B” led by Lieutenant Gottlieb was off Omaha Beach and landed on June 9, during which two trucks sank. Their voice-intercept operations started on June 11 at Cricqueville-in-Bessin two miles south of Pointe de Hoc. By the end of the month the balance of Det. “B,” all of Det. “A,” and the nucleus of “C” were all dug-in in adjoining fields. “C” was awaiting the organizing of the XIX Tactical Air Command, to take place when Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army went into action. This was the only period until the war ended that all detachments were “together.” After the breakout from Normandy, “B” and “C” went with the First and Third Armies respectively and “A” served both 8th Air Force Headquarters and SHAEF.

With experienced British officers as teachers, we received hands-on training with real-time German messages at various places throughout southern England. The British proved to be excellent instructors and apparently we were apt pupils. On The D-Day Invasion, a 20-man echelon of Detachment “B” led by Lieutenant Gottlieb was off Omaha Beach and landed on June 9, during which two trucks sank. Their voice-intercept operations started on June 11 at Cricqueville-in-Bessin two miles south of Pointe de Hoc. By the end of the month the balance of Det. “B,” all of Det. “A,” and the nucleus of “C” were all dug-in in adjoining fields. “C” was awaiting the organizing of the XIX Tactical Air Command, to take place when Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army went into action. This was the only period until the war ended that all detachments were “together.” After the breakout from Normandy, “B” and “C” went with the First and Third Armies respectively and “A” served both 8th Air Force Headquarters and SHAEF.

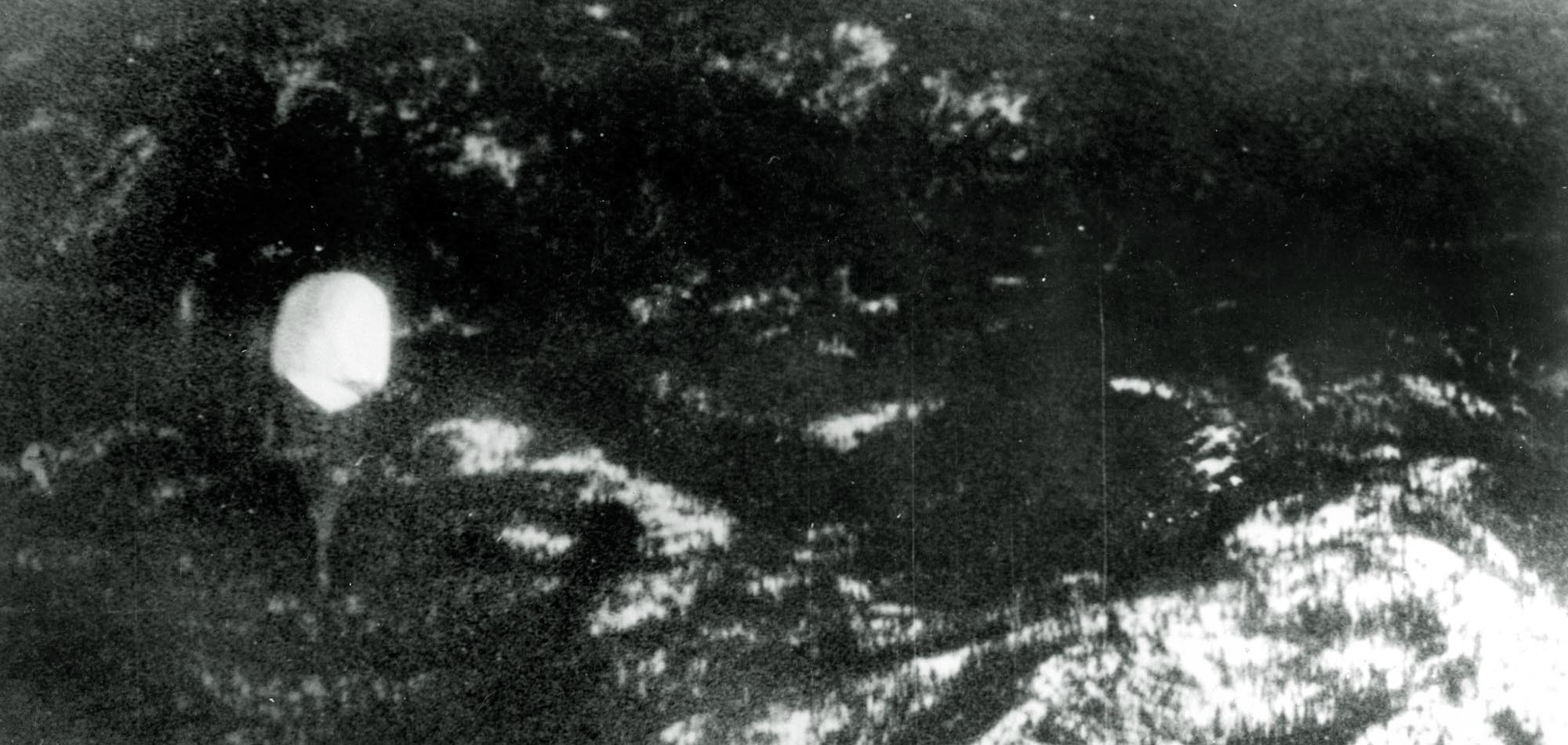

On the night of July 21 my squadron had a weird experience. The usual German night intruders were overhead trying to drop their mines to interfere with our unloading operations at Omaha Beach, and our usual antiaircraft “Fourth of July” show was in full visual and sonic bloom when suddenly, Corporal Albert Gruber, monitoring his Hallicrafter intercept set, heard a panic-stricken German pilot announce, “I’ve been hit—am losing altitude—must get rid of my load.” Before Gruber had finished writing this down on his message pad he saw a blinding flash in the field adjoining his and seconds later a blast wave knocked him off his chair.

My detachment (“A”) was in the adjoining field and I was hunkered down in my foxhole watching this Heinkel 111, tail aflame, coming in ever lower and suddenly, in the light of our exploding ack-ack fire, seeing several parachutes drop from the stricken aircraft. These were concussion mines. Some exploded setting off our own thermite grenades, kept on or in the vans to destroy them in case of imminent capture. The pressure wave from the grenades pressed me down in my hole as if an elephant were standing on my back.

About a week later the Allies broke out of their breachead, and within a few days Det. “A” left Normandy via Avranches and set up operations at the small village of Parné-sur-Roc near Laval. Our stay there was marked by a flood of activity because many German units, in retreat, were sending panic messages, some poorly enciphered, a few even “en clair.”

Cracking the Code

It was at Parné on August 13 or 14 that we intercepted a message that I recall playing an important part in breaking. Traffic analysis identified the call sign as being that of a German reconnaissance squadron. Direction finding added that the flight originated from La Spezia in Northern Italy and that the aircraft was flying westerly along the Mediterranean littoral. Armed with this information and the fact that the previous duty shift had already postulated the letter “J” I stared at the message with my mind on idle, until, suddenly, in an intuitive spurt the name of the Corsican port of Ajaccio came to me.

This helped break the entire message and we found that the German plane was reporting on a concentration of Allied landing craft in the harbor of Ajaccio. (They were to be used one or two days later for the landings in Southern France.) Ninth Air Force H.Q. became very excited when they received our break. They bombarded us with all sorts of questions. To this day I am not certain about their reasons: whether they hadn’t been previously informed about the new landings or whether they wanted to know more about what the Germans had observed.

A few days later, as Paris was being liberated, we hastily packed up and raced to Chateau Beaumont, the recently evacuated headquarters of the Luft Funkhorch Regiment West, our counterparts, located in La Celle St. Cloud just west of Paris.

The heated barracks with beds and bath were a far cry from the foxholes of Normandy. And in the Chateau proper the code-breakers occupied the tower rooms with a fireplace and a superb view of Paris down the silver lane of the Seine while the intercept operators set up their equipment in the Grand Ballroom. We stayed at La Celle St. Cloud while our “voice” detachments went on to the Ardennes in Belgium (“B”), East of Nancy (“C”), and the newly formed (“D”) at Fouron St. Pierre on the Belgo-Dutch border.

Tracking the German Anti-Aircraft Guns

During the next several months Det. “A,” still at Chateau Beaumont, monitored and decoded messages as usual. We had many adventures during this time, but at 0415—it was December 16—out of the silence of the night, the radios of Det. “A” came alive with a short but hastily sent message. It was unusual to get such traffic at night. The intercept operator took the message up the stairs to the Tower, where in front of a crackling fire, the midnight-to-0800 shift of code-breakers was on duty.

The cryptanalysts had barely started to work on the message, when, at 0419, a second message, exactly repeating the first, was brought in. Eyebrows were raised. Most unusual. This was the first time in their experience that a message had ever been duplicated. It eliminated the possibility of corruption in the code groups or a decryption error.

We quickly identified the German encryption. It was one of a family of codes we had named after musical composers, an “elgar” used by the Germans to contact their antiaircraft units. It was quickly broken, and we read “… 90 JU 52s and 15 JU 88s going from Paderborn area to area 6˚-6˚ 30´, E to 50˚ 31´-50˚ 45´ and returning by same route.” We plotted the co-ordinates on our maps as between Hofen and Monschau on the Belgo-German border. In the dim light of the tower room, eyebrows went up even higher. JU 52s were transports. JU 88s were versatile aircraft used as bombers, night fighters and occasionally as transports; we thought they would be used as transports. Never had the Germans used 105 transport planes at night.

The consensus was that so many aircraft flying into Allied airspace had to be an airborne-operations parachute drop. Our usual addressees—9th Air Force H.Q. in Luxembourg City, IXth TAC in Verviers, SHAEF at Versailles and A14F (Air Ministry Intelligence, London) were promptly notified, and in traditional fashion we received the standard “QRV”—message received.

At 0549 that morning we received a third message. It canceled the operation. This we also sent on to the higher headquarters.

De-Classification in 1996

Whatever use the Allied commanders made of our decodes remains a matter of conjecture. The fact is that the Germans did make the parachute attack early on the following morning, December 17—instead of the 16th—along the Eupen-Malmedy road having flown over the frontier between Hofen and Monschau. It was the early strike of the massive morning attack of three German armies to turn the tide of the war in the West, and launched what we call the Battle of the Bulge. Fortunately for the Allies, the delays, confusions and outright incompetence connected with German “Operation AUK” (also known as Operation STöSSER) resulted in a catastrophic drop for 1,200 Fallischirmjäger that on a smaller scale was worse than the fate they had suffered in Crete in May of 1941.

Records show that American antiaircraft battalions (possibly informed by 3rd R.S.M.’s alert) took a heavy toll on the German transports that morning. To add insult to injury, many German antiaircraft units, apparently never receiving the messages sent by Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich von Der Heydte, the paratroop commander, shot up and shot down many of their own planes.

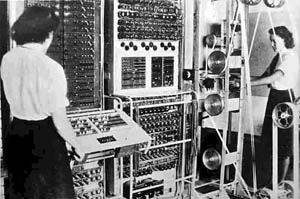

The cryptanalysts of detachment “A” as well as various RAF Wireless Units and Hut 3 at Bletchley Park, which apparently also took down some or all of the messages, had to wait until mid-1996, when our National Security Agency finally declassified all the documents. They then learned, “The only advance intelligence of the German offensive received in low-grade air codes was the warning of the parachute landings.”

It is obvious that two hours’ warning is not very much but certainly higher headquarters should have been alerted by this unique message that meant that something more than a local counterattack was afoot.

A Mexican Standoff in Belgium

For the 3rd R.S.M. there was another, even more bizarre aspect to the confusion. Our venerable detachment “B” was encamped astride the Eupen-Malmedy road. Headquarters and the voice interceptors were lodged in the town of Jalhay west of the road but the Direction Finding Vans were located at Baraque Michel and Mt. Rigi, the highest points in Belgium, east of the road. The remnants of von Der Heydte’s parachute force (less than a hundred men) landed right between them.

Major Silverstein, Det. “B”’s commander, had been alerted to “A”’s break of the paratroop message, but only knew what direction the Germans were taking, not how deep into Allied territory they were flying. He was rudely shocked when men of the morning duty shift on December 17 ran in, carrying empty German parachutes they had picked up in the woods near town. When Sergeant Bob Siefert led his crew out to relieve the D/F operators he noticed some men filtering through the trees, but it was the guard in front of one van who cautioned him, whispering that he suspected they were Germans.

A Mexican standoff developed. The Germans were too weak to provoke a battle, and our men, armed only with carbines, were certainly not going to take them on. Major Silverstein, fearing capture and the compromise of our secret operations, contacted IXth tac in nearby Verviers requesting permission to move out immediately. But IXth tac as well as 9th Air force H.Q., were still completely unaware of the extent of the attack and advised him to wait. By day’s end, however, Silverstein took matters into his own hands and ordered “B” to move north and join Det. “D” at Fouron St. Pierre on the Dutch border. It was good that he did so because by that time a German battle group under Joachim Peiper was already threatening to capture Malmedy.

Fading Into History

In the spring of 1945 the 3rd Radio moved into Germany with the various Allied armies. Det. “A” took over a “Kurhaus” and a school (used as barracks) in the little village of Bad Vilbel near Frankfurt-am-Main presumably to be nearer to SHAEF.

When the war ended in May the other detachments eventually all moved in with us. Once the war with Japan was over, the majority of the squadron was sent home. I was discharged the day before Christmas 1945. A skeleton unit, called the 2nd—Radio Squadron under ex-Lt. Maj. Mortimer Proctor stayed on until the spring of 1946, and then it also faded into history. Interestingly, during the Korean War, the 3rd Radio was reconstituted and served for over a year in Alaska monitoring Korean and presumably Russian transmissions.

Very interesting article. Was a Korean linguist when an enlisted man nearly a half-century ago.