By Robert Suhr

From the deck of the Hartford, Flag-Officer David Farragut watched his signal officer in the rigging above him. When a 285-pound mortar shell landed in Fort Jackson, the signal officer waved a red flag. When the shell did not explode on target, he waved a white flag. The signal officer waved the white flag more often than the red.

“I guess we go up the river tonight,” someone overheard Farragut mutter.

With this decision, Farragut started events that would lead to an attack on the largest city in the Confederacy—New Orleans. As a banking center, and the major port for exports coming down the river, it was a rich prize indeed. But to get at the city, Farragut’s ships would have to do what many experts considered impossible: steam up the lower river past two powerful forts built especially to prevent such an excursion, forts Jackson and St. Philip.

The Union Eyes New Orleans as a Key Target

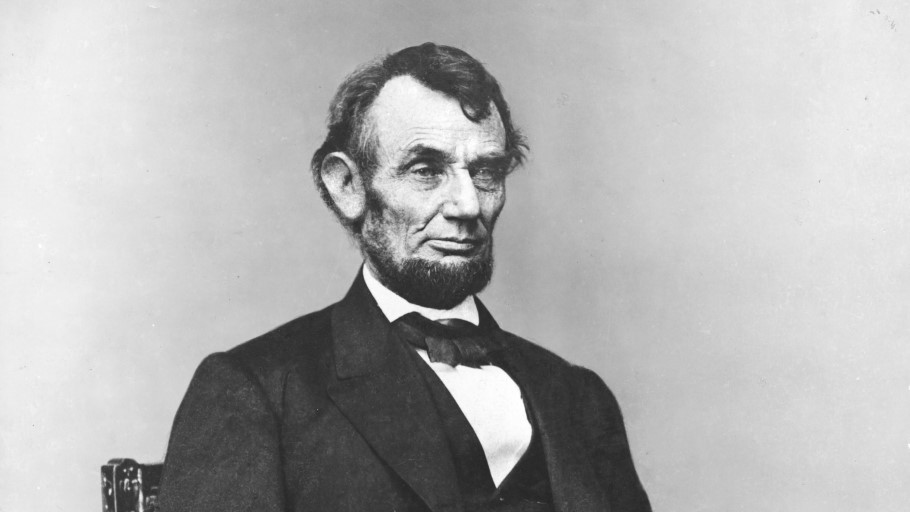

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox first proposed running the ships past the forts in the summer of 1861. The proposal countered prevailing naval thinking that wooden ships could not stand against forts. But early Union naval victories along the Atlantic seaboard had convinced him it was not true. He persuaded Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles to suggest the scheme to President Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln was not enthusiastic about the operation until Commander David Porter arrived in Washington in November. Porter’s idea was much the same as Fox’s. Having spent 76 days on blockade duty outside the mouth of the Mississippi, Porter had one thing Fox lacked—current information on Confederate defenses.

After Porter explained the situation to Lincoln, the President said, “This should have been done sooner. The Mississippi is the backbone of the Rebellion; it is the key to the whole situation.”

With Lincoln convinced, they had to get help from the army. The navy intended to capture New Orleans, but it needed troops to garrison it first.

Major General George B. McClellan had just replaced Winfield Scott in command of the Union armies when they called upon him. Despite the situation, McClellan always believed the enemy had many more troops than he did. So he approved the attack on New Orleans, so long as he did not have to send any troops from the Army of the Potomac.

This set the stage for the emergence of one of the most controversial figures of the Civil War: Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler. A “War Democrat” from Massachusetts, Butler was a man whose support Lincoln needed. In addition, Butler offered to raise several regiments in New England. But because McClellan did not like him, he ordered Butler and his newly-raised regiments to the New Orleans operation.

Fox had proposed steaming past the forts, but Porter thought the Union forces first needed to reduce the forts by smashing them with 13-inch siege mortars mounted on the decks of ships. Consequently, Welles gave Porter command of a mortar flotilla with the authority to outfit 20 schooners to serve as “bomb vessels.”

At about the same time in Missouri, Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont came to a conclusion similar to Porter’s. He ordered the construction of 40 “mortar boats” to reduce Confederate fortifications along the central Mississippi. He already had a foundry in Pittsburgh casting the giant guns. But Porter got Washington to intercede, resulting in the foundry shipping the first 20 mortars to New York for mounting on his schooners.

Attached to the mortar flotilla were six gunboats. Some were converted ferry boats that were so strong Porter could use them as tugs to maneuver the mortar schooners in the river.

Enter David Farragut

The man Welles wanted for overall command of the expedition was Porter’s foster brother, 60-year-old Captain David Farragut, who had impressed Welles with his boldness during the Mexican War. But the appointment was not without criticism. Some questioned Farragut’s loyalty; he was born in Tennessee and had spent a number of years in Louisiana.

So Welles first sent Porter to question him. He then summoned Farragut to Washington, where Farragut met with Fox and Postmaster General Montgomery Blair. Fox gave Farragut a list of ships and asked if he could take New Orleans with them. After scanning the names, the venerable captain told Fox he could do it with two-thirds their number. Blair went to Lincoln convinced Farragut could take New Orleans.

When Farragut met with Welles, the secretary told him about the mortar attack that was to precede the run past the forts. Farragut agreed to use the mortars if ordered to, but he doubted they would be effective. He ventured the opinion that they might even be counterproductive because they would warn the Confederates that an attack was coming.

Through all this Welles and Fox kept the operation a secret. They even kept Secretary of War Simon Cameron ignorant of it. An unexpected benefit of this secrecy was the Confederate authorities’ fixation on the ironclads under construction near St. Louis. Confederate authorities in Richmond became convinced that the main threat to New Orleans would be a strike from the north.

Farragut Assembles His Fleet

The fleet placed under Farragut’s command was comprised of the Colorado, a 40-gun steam frigate, four sloops carrying 22 to 24 guns each, the side-wheeler Mississippi with 17 guns, three corvettes each with seven to nine guns, and eight gunboats carrying two guns each. The gunboats had a heavy and a light gun on pivots so they could fire to either side. None of the ships could fire at a target immediately in front of it.

In mid-March, the Union navy entered the Mississippi Delta at Pass à l’Outre. Getting across the bar was difficult. The crews had to remove guns, coal, sails and spars from the Pensacola and Mississippi to usher them across. The Richmond ran aground seven times trying to cross. When all the mortar schooners were across, Porter sent his steamers back to help the warships.

But the mighty Colorado would not pass over the bar, even unburdened of guns and much equipment. Farragut tried for two weeks to nurse it across before giving up. By leaving her behind, he lost almost 20 percent of his firepower.

Still, Farragut had several intangible advantages. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had built and maintained forts Jackson and St. Philip. Before leaving Washington, Welles gave Farragut detailed engineering drawings of both forts, plus a detailed description by Brig. Gen. John Barnard, who had helped rebuild them.

Farragut also had a ship from the U.S. Coast Survey. He sent it ahead to find the best channel over the bar. In addition, while the warships prepared for fighting in the river, the surveyors established landmarks so Porter would know the exact distance and angle to each fort, even if the forts were not in sight. White flags along the shore showed where each mortar schooner was to anchor, and how far it was to the center of each fort.

In mid-April 1862, one year after the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston, the Union warships and mortar schooners moved up the river. On April 16, Farragut authorized Porter to begin the bombardment when he was ready.

Fort Jackson was on the western bank on the inside bend of the river, and its defenders had cut down trees to give themselves a clear view of part of the river below them. Fort St. Philip was farther upriver on the eastern bank. Porter placed the 1st and 3rd divisions of his flotilla on the west bank of the river so the lead schooner was exactly 2,850 yards from Fort Jackson and 3,680 yards from Fort St. Philip. From the masts, lookouts could see the forts, but to disguise the masts rising above the trees they covered them with brush.

The 2nd Division was set on the east bank, 3,680 yards from Fort Jackson, in full view of the Confederate forts. By the morning of April 18, Porter was ready to begin the attack.

Were the Confederate Defenses are Strong as the Union Believed?

The defenses Farragut faced seemed formidable, but reality might have been less so. The Confederates had a large variety of weapons and commands to oppose an advance by the Union navy, but that diversity harbored weaknesses.

The heart of the Confederate defenses were the two masonry forts. These, plus available ships, comprised 192 guns, but only one-third were large caliber (32-pound and larger). When Maj. Gen. Mansfield Lovell took command in December, he tried to secure larger guns but the Richmond government deemed his department a low priority.

Lovell decided that the forts would be effective only if the Union navy could be forced to remain stationary in front of them. To stop their advance, he built a barrier across the river five-hundred yards below Fort Jackson. His men built what he called a “raft” across the river. This raft was composed of cypress logs, four or five feet in diameter and 40 feet long, chained together with two-and-a-half-inch iron cables. Fifteen anchors at the end of 180-foot chains held the raft in place.

Unprecedented high water in March tore part of the raft away. Lovell repaired the barrier by chaining together seven or eight derelict boats in the opening.

Lovell recognized how vulnerable New Orleans was. The Confederate authorities in Richmond saw the direct threat to the Crescent City as a thrust up the river, but there were also a dozen bayous and canals that could allow the Union navy to outflank the forts.

Lovell thus established two lines of defense for New Orleans. Brigadier General Johnson Duncan commanded the outer line, forts Jackson and St. Philip, which blocked the direct approach from the sea. An interior line guarded the city proper from land attacks by forces that may have avoided the forts. This line ran from Chalmette on the river to Lake Ponchartrain north of the city. More fortifications protected the western bank of the river, and New Orleans from the north and west.

To add to his difficulties, Lovell had trouble keeping troops and weapons in New Orleans. When Albert Sidney Johnston collected troops for the offensive that ended at Shiloh, five thousand of Lovell’s men transferred to Corinth, taking with them most of the weapons Lovell had. When the state of smuggled muskets through Florida, the governor of Florida seized half the shipment.

Lovell’s Meager Confederate Navy

The real key to defending New Orleans against a naval attack was a Confederate navy. Unfortunately, in 1861, the priority for the Confederacy was building an army and not a navy.

One of the few ships Lovell did have was the ironclad ram Manassas. Perhaps an early success deluded Confederate officials into thinking they had nothing to fear from a Union navy attack up the Mississippi.

That story goes back to May 1861, when John Stevenson began converting the steamer Enoch Train into an ironclad commerce raider he named the Manassas. Five months later, Lieutenant Alexander Warley seized the ship for the Confederacy. The Manassas was poorly armed, but Warley intended to use her as a ram. Unfortunately the Manassas was so slow it could barely move against the current.

The day he seized the Manassas, Warley led some converted wooden gunboats against the Union blockade at the Head of the Passes, where the Mississippi River, well below New Orleans, branches in to three major outlets to the Gulf of Mexico and where the Union flotilla was gathered. An attempt to ram the Union ship Richmond failed, and the supporting gunboats did not arrive. Nevertheless the Union navy fled outside the bar and remained there until Farragut’s arrival in March 1862.

To create ships that could stop the Union navy, Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory issued contracts for the building of two new ironclads, the Mississippi and the Louisiana. But the designs of the ships were ambitious—the Mississippi, if completed, would be the most fearsome and swiftest warship ever made—and beyond the capability of the South to build from scratch. The completion dates continued to slip from one delay after another.

What Lovell lacked in solid warships he made up for in diversity and numbers. Besides the Manassas, he had several wooden gunboats converted from civilian use early in the war. The state of Louisiana also had its own gunboats. In addition, there was the River Defense Fleet, six river steamers turned into rams and commanded by John Stevenson, the same man who had built the Manassas.

Commanding the Governor Moore, a Louisiana state sidewheeler, was Captain Beverley Kennon, a former U.S. navy officer. After the war, Kennon described his ship (and the others similar to it): “Her stem [bow] was like that of hundreds of other vessels, being faced along its length on the edges above water with two strips of old-fashioned flat railroad iron, kept in place by short straps of like kind at the top, at the water-line, and at three intermediate points. These straps extended about two feet abaft the face of the stem, on each side, where they were bolted in place. The other ‘rams’ had their ‘noses’ hardened in like manner. All had the usual-shaped stems. Not one had an iron beak or projecting prow under water.”

The Confederate defenses lacked weapons, men and ships. But perhaps the worst flaw was the command structure. Lieutenant Colonel Edward Higgins commanded the forts, but had no authority over the ships next to them. Mitchell commanded the Confederate navy, but his authority extended only to the Confederate ships—the ships of Louisiana did not have to follow his orders. Stevenson made it clear that the River Defense Fleet was taking orders from no one. “Every officer and man on the river-defense expedition joined it with the condition that it was to be independent of the Navy, and that it would not be governed by the regulations of the Navy, or be commanded by a naval officer.”

The Bombardment of Forts Jackson and St. Philip Begins

When the mortars opened fire on the morning of April 18, the guns in the two forts returned the fire. Because of the work by the surveyors, the mortars quickly found their targets. The Confederates took longer to find their marks, and their fire concentrated on the exposed 2nd Division. To try to suppress the Confederate fire, Porter sent the gunboat Oswego to the head of the second division to fire its 11-inch smoothbore. She stayed there under fire for almost two hours, retiring only when she ran out of ammunition.

At about five o’clock, the Union officers saw fire near Fort Jackson. Most believed it was a fire raft but Porter went up the river after dark to get a better view. He reported to Farragut that he thought the fort was on fire. Indeed, several years later, an officer inside the fort wrote Porter that “… the citadel and all buildings in rear of the fort were fired by bursting shell, and also the sand-bag walls that had been thrown around the magazine doors. The fire, as you are aware, raged with great fury, and no effort of ours could subdue it.”

On April 19, Confederate tugs maneuvered the Louisiana down to Fort St. Philip where they anchored her. Mechanics then came down to install her machinery while sailors installed cannon. But to the dismay of her commander, John Mitchell, the ports were too small to aim the cannon. Thus after the war Kennon wrote sarcastically that the Louisiana “could float and do nothing more.”

Higgins wanted Mitchell to deploy the Louisiana downriver where her guns could drive off Porter’s mortar schooners, but he refused. He cited several reasons, perhaps the most compelling being that a hit from one of those massive mortar shells would send the ironclad straight to the bottom.

The Itasca and Pinola Attempt to Clear the River Barrier

By the third day, Porter’s bombardment neared its end. The crews had fired about 16,800 shells and were almost out of ammunition. Farragut summoned his ship commanders to a meeting at 10 pm to discuss alternative courses of action. John Alden, captain of the Richmond, read a letter from Porter to Farragut complaining that the defenders would cut the ships to pieces unless Farragut gave Porter’s mortars more time.

There was also the problem of the make-shift barrier across the river. To overcome it, Lieutenant Charles Caldwell of the gunboat Itasca, volunteered to cut an opening in the barrier if a second vessel helped. Farragut decided Caldwell could not control his ship in the channel and command the operation at the same time. So he put Commander Henry Bell in command of the Itasca and Pinola with orders to make an opening in the barrier during the night. Thus during the day, the crews of the two ships removed the ships’ lower masts and rigging. That night, before the moon rose, they maneuvered the two vessels upriver to the barrier.

To keep the Confederates pinned down, the mortar boats increased their rate of fire. As the gunboats approached the raft, they fired a couple of rockets. The forts opened up, but their shots were high. Once the two Union ships were against the barrier, the Confederates had trouble distinguishing them from the hulks, and the ships went about their mission without further interference.

The Pinola moved up to the third hulk from the eastern shore. Her crew set gunpowder chargers to blow the chains that connected it to the ships on either side. They also rigged a torpedo with an electric detonator to go off under the bow. But the Pinola backed away faster than the operator could lay out wire and it broke. To add to the frustration, the fuses on the other two charges failed to ignite.

Over on the east side, the Itasca ran a grappling hook to the railing on the shore-side hulk. As the current pulled the gunboat downstream, the railing broke off. The Itasca then moved up to the barrier again. This time Caldwell kept the engine running to keep her in place. His plan was to blow the chains loose, but the crew discovered one chain was merely wrapped around the anchor chain. When they dropped the anchor chain in the water, it carried the second chain with it. Freed of the restraining chain, the hulk and the Itasca drifted down the river and became lodged upon the eastern riverbank.

Caldwell then sent a boat to the Pinola, which was steaming upriver to try again. The Federals ran two ropes to the stranded Itasca, but she was so hard aground that both ropes broke trying to loose her. A second try with a large hawser then pulled the Itasca free.

But instead of returning to safety, Caldwell took the warship past the barrier along the bank until she was almost to Fort St. Philip. He then ordered the Itasca about and surged full steam toward the barrier. Driving the bow between the third and fourth hulks, Caldwell broke the chain and created a large gap in the obstruction. The Pinola followed, cutting another opening through the linkage of hulks, logs and chains.

The Full Attack Begins on April 23

Knowing this, Farragut wanted to run past the forts on the night of the 22nd, but the Mississippi (not to be confused with the incomplete Confederate ironclad) was not ready. During the day, British and French naval officers came down from New Orleans. They warned Farragut that the forts would destroy his fleet if he tried to steam past. When Farragut repeated their report to Porter, the latter promised that with another day’s bombardment he could ensure that they would pass with the loss of no more than one ship.

Thus Porter’s mortar schooners continued to bombard the forts for another day, but without damaging them any further. In fact, both Confederate and Union officers would later state that when Farragut moved against them, the two forts were as strong as they had been before the bombardment began.

But now the crisis was at hand. On the 23rd, the Confederates knew something was imminent. Lookouts saw the surveyors planting new flags along the riverbank upriver from the position of the mortar schooners. Many believed Farragut intended to use his gunboats to attack the forts.

The Confederate ships lined the riverbank north from Fort St. Philip. The ram Stonewall Jackson was farther upriver to guard the canals in case Farragut chose to bypass the forts.

Mitchell sent a steam launch downriver to serve as a lookout, ordering its commander to light a signal fire if the Union ships advanced.

Farragut divided his flotilla into three divisions. His own command had only three ships in it, but they were the largest: the Hartford, Brooklyn and Richmond.

In his initial plan, Farragut intended to lead the attack and crush any opposition with the firepower of these ships. His lieutenants argued that leading from the front was unwise for the commander. So Farragut agreed to let Captain Theodorus Bailey lead the attack with a division comprised of eight lesser ships. Farragut’s flotilla would be in the middle, and Bell would bring up the rear with a division of six small gunboats.

Farragut also gave Porter a role to play in the attack. The mortars would suppress the fire from the forts with a barrage, while the gunboats attacked the water battery below Fort Jackson.

At 1:55 am—it was now the early morning of April 24—the Hartford raised two red lights, the signal to advance. For an hour and a half Farragut waited while the ships pulled in their anchors. It was not until almost 3:30 before the Cayuga had her anchor in and could start forward.

At the approach of the Union ships, the Confederate lookouts fled to the swamps without lighting the signal fire. Thus with as little noise as possible, Bailey’s ships moved toward the gap in the barrier. At the water battery, Confederate artillery officers could see movement, but were unsure what it was.

On board the Louisiana state side-wheeler gunboat Governor Moore, Kennon thought he heard the splashing sound of the Mississippi’s paddle wheels. He descended toward the river to try to get in a better position to hear. As he reached the deck, cannon in both forts opened fire and the Union ships returned it.

“The bursting of every description of shells quickly following their discharge, increased a hundred-fold the terrific noise and fearfully grand and magnificent pyrotechnic display which centered in a space of about 1,200 yards in width,” Kennon later wrote.

The Cayuga, mounting four guns, led the Union line forward. She passed through the hulks without incident. But as she approached the forts, cannon fire began to hit her before she could fire back.

The Confederate Fleet’s Chaotic Start

Kennon ordered his crew to get the steam up on the Governor Moore. In three minutes she was ready to sortie but found herself in chaos at the Confederate position. Until the Manassas moved, the gunboat was trapped where she was. On the Manassas, Warley cast the lines off from the tug and turned the ram’s bow to move downriver. As the ironclad started to turn, the Moore started forward and immediately collided with the tug Belle Algerine.

The Manassas steamed down the river faster than Warley thought possible, but still, the ironclad was slow. The first ship she encountered was the River Defense Fleet ram Resolute, which she struck on the side. She then exchanged shots with the Mississippi, which steamed away. Next she tried to ram the Pensacola, but that Union ship deftly maneuvered out of the way.

Warley knew he could not keep up with the ships moving upriver so he decided to go down to engage the mortar fleet. When the Manassas was between the forts, both opened fire on the ship, mistaking it for a drifting Union vessel. He turned the bow of the ironclad upriver.

With no room to ram, Kennon took the Moore up the east bank of the river until he could get a chance to turn and come down with the current. This would also get him out of the way of the fire between the forts and the Union ships.

Meanwhile Porter ran his steamers up alongside the levee just below the water battery. When the Confederate forts opened fire, his ships delivered a broadside of 27 guns into the Confederate batteries. The Confederates returned fire, but the levee protected the hulls of the steamers. Confederate shells passed through the rigging but did no major damage. Porter thought he had silenced the guns in the water battery after 10 minutes, so he gave the order to fire at Fort Jackson.

Upstream from the forts a fight erupted between the Union ships and some of the Confederate fleet. Trying to help, Kennon turned the Moore downriver to attack and found the Union ships Oneida and Cayuga to his port. To the challenge, “What ship is that?” and knowing the only Union paddle-wheeler was the Mississippi, he called back: “United States steamer Mississippi.” But the blue identification light on the Moore’s mast revealed her identity. The Oneida gave her a broadside. Others joined in raking the Confederate gunboat, killing crew members at the bow guns and in the bunkers.

Then the Varuna shot past the Moore on her way upriver. Kennon knew General Duncan was on the steamer Doubloon not far ahead so he decided he had to do something to delay or destroy her. To hide the identity of his ship, Kennon used a musket to shoot out the identification lantern. He ordered the crew to show white and red lights like the Union ships.

The Varuna had a half-mile head start when the Moore turned upriver and started after her. But the gap separating them lessened with each minute because steam pressure was low in the Union ship. Kennon poured oil on the coal to make it burn hotter. The two vessels overtook and passed the ram Stonewall Jackson, struggling in a maneuver upriver against the current.

Meanwhile the three largest Union ships blasted the forts. Confederate Lt. Col. Higgins exclaimed, “Better go to cover, boys; our cake is all dough!”

The passage was not without incident. When the Hartford unleashed her first broadside, the smoke hid her from the Brooklyn. Captain Thomas Craven thought he saw the flag ahead of him. Suddenly the sloop shuttered as she ran over one hulk in the river. A few minutes later she did the same to one of the moored tree trunks. Then she almost ran aground under the walls of Fort St. Philip.

As the Brooklyn passed Fort Jackson, a shot struck the rail and plowed into the deck. Another cut the signal quartermaster in half. When abreast of the fort, two shots hit near a gun, decapitating the gun captain and wounding nine men.

Then the Richmond, which was a slow ship, became entangled in the barrier. She ran so close to Fort Jackson that Alden would write that they could have thrown a stone from her deck into the fort.

When the Hartford was beyond the forts, Farragut saw a fire raft come toward them, pushed by the tug Mosher. When Farragut gave the order “Hard-a-port!” the Hartford moved only a short distance before running into the bank. They were so close to Fort St. Philip that they could hear gunners giving orders. Actually, they were even closer than the Confederates thought; the Rebel shots passed overhead without doing any damage. Then the tug pushed the fire raft up against the Hartford. But a broadside from the Union sloop sent the tug to the bottom.

On the Hartford’s deck, the fire rafts made it as bright as noon. The danger to the ship was severe. An officer passing Farragut heard him exclaim, “My God, is it to end in this way?” But the crisis passed when a master’s mate climbed into the rigging with a fire hose and put out the fire.

As the Brooklyn passed Fort Jackson, its crew saw the Hartford on the bank with flames running up the rigging. Craven ordered the engines to a halt. The Brooklyn fell downriver until she was between the fort and the Hartford.

The Confederates then renewed their fire on the Brooklyn, but they aimed high; their shots passed through the rigging. The Brooklyn returned fire from its port battery as fast as the men could load and fire.

The Brooklyn’s Double Escape

Meanwhile Farragut gave the order to reverse engines, and the Hartford freed itself of the bank and the fire raft with a jolt. Seeing the Hartford free, Craven took the Brooklyn farther upriver. As she passed Fort Philip, her guns raked the Confederate batteries with canister. The Confederates opened fire with muskets, but after suffering a few shots of grape, they stopped.

Beyond Fort St. Philip the Brooklyn saw the Louisiana tied up to the bank. Craven ordered his crew to load round shot in the starboard battery. The ironclad, though, got off the first shots, firing as the Union warship approached. Then, as the Brooklyn began to pass, the Louisiana’s crew closed the port shutters so the balls from the broadside bounced off.

One of the Louisiana’s nine-inch shots had struck the Brooklyn about a foot above the waterline, passing through three feet of wood before stopping. When the Brooklyn’s crews later dug out the shell, they discovered that in the Louisiana gunners’ haste to fire, they had failed to remove the lead patch from the fuse so the shell could not explode. Had it gone off, it would have blown off the bow of the Brooklyn and sunk her.

A few moments later a lookout on the Brooklyn yelled, “A steamer coming down on our port bow.” Midshipman John Bartlett went to the poop ladder to get a better look. “I … saw a good-sized river steamer coming down on us, crowded with men on her forward deck, as if ready to board. The order had already been given, ‘Stand by to repel boarders,’ and to load with shrapnel; the fuses were cut to burn one second.”

Craven gave the order to bring the bow to starboard. As the guns came to bear, the Brooklyn and the Confederate attacker each opened fire, the shells exploding as they left the muzzle as though they were huge shotguns. By the time Bartlett’s No. 10 gun was in position, he could no longer see the target through the smoke.

Men looking through the ports yelled out, “The ram, the ram!” Craven called out, “Put your helm hard-a-starboard!”

But it was too late. The impact threw Bartlett from his feet. “I ran to the No. 10 port, the gun being in, and looked out, and saw her almost directly alongside. A man came out of her little hatch aft, and ran forward along the port side of the deck, as far as the smoke-stacks, placed his hand against one, and looked to see what damage the ram had done.…” Before he could return to safety, a fellow crewman on the Brooklyn knocked him into the water.

It was the ram Manassas, which had smashed into the Brooklyn at a full coal bunker. Craven sent a carpenter below. The man reported little damage, but when the crew later emptied the bunker, they discovered how severe the impact had been. Had the Manassas rammed her almost anywhere else, the blow would have sunk her.

The federal 3rd Division then started through with little trouble. There were so many Union ships, however, that it was daylight before the final three began their run past the forts. The Kennebec led the Itasca and Winona into the barrier, where they became stuck. A shell struck the boiler of the Itasca. As she drifted down the river, Caldwell ordered the crew to lay down on the deck until they were out of range. The Winona tried going through in daylight and was badly shot up.

The Confederate gunboat McRae fired at every Union ship as it passed, but most did not fire back thinking she was a Union vessel. Its luck ran out with the 3rd Division, however. Most of the shots from the Union gunboats missed, but one started a fire. Three were disgorging broadsides at the Confederate ship when the Manassas chased them off. The McRae then drifted down to Fort St. Philip.

The Sinking of the Varuna

Farther upstream, as they approached Chalmette about dawn, Kennon gave the order for the Moore to fire at the Varuna. The two ships traded shots with neither hitting. Kennon thought the Union ship was afraid of giving her a broadside for fear the Moore would ram her.

Because the bow gun on the Moore was in the wrong position, Kennon ordered a shot through her deck to try to reach the Union ship’s boilers. The tactic worked. Moore’s first shell hit went through the Varuna’s smokestack. A second shot disabled a pivot gun.

Then the Governor Moore rammed the Varuna twice. Next, the Stonewall Jackson rammed her twice on the other side. The impact of ramming the Union ship broke a steam pipe connection on the Jackson, crippling her. The Varuna then ran her into shoal water where she sank.

Kennon’s moment of triumph on the Moore was brief. More Union ships came into sight. He gave the order to ram but gunfire raked the Governor Moore before she could close. With 54 killed and 17 wounded out of a crew of 93, Kennon ordered what remained of the crew to burn the ship.

North of the forts, at Quarantine Point, Farragut gathered his ships. When the Manassas appeared after dawn, he shouted the order, “Send the Mississippi to sink that damn thing!” As the paddle-wheeler turned downriver, the Kineo joined her.

Thus Warley saw two warships bearing down on him. With his cannon disabled and unable to ram against the current, he decided his duty lay in trying to save his crew. He ordered them to run the ironclad up on the eastern river bank. His crew escaped through a front gun port to the swamps beyond the river.

Farragut and Porter Wrap Up the Mission

Farragut now took stock of the situation. He had one ship sunk, the Varuna, and three missing. Most of the Confederate ships had been sunk or destroyed. He sent the Cayuga on up the river and the Mississippi back down to stand guard.

He then ordered the remainder of his fleet up to New Orleans—the navy had done the fighting, and he wanted to ensure that the city surrendered to it and not to Butler’s troops. Craven had warned him six weeks before that if the attack failed, the failure would be attributed to Farragut, but that if it succeeded, credit might well go to Porter and Butler.

Down at the forts, Porter demanded surrender. When Higgins refused, the mortar schooners opened fire again with the same lack of success. Not until Porter sent some of Butler’s troops through the bayous to land behind the forts did Higgins agree to capitulate.

The fight for one of the richest prizes of the Confederacy was all but over. With its port city at the mouth of the Mississippi in federal hands its potential exports of cotton and grains was bound to suffer. For the South, it was a grievous loss, and one never retrieved.

For Farragut, New Orleans was only a step to further triumph as he worked his way north, increasingly cutting the Confederacy between eastern and western parts. The severance would be complete when Farragut teamed with Ulysses Grant to wrest the South of Vicksburg.

Great writing!!!

Some years ago I took a trip up river from the entrance at the gulf to the city proper. I was amazed at the narrowness of the river in some places. A proper placement of guns on the river bank could have caused severe damage to Farragut’s fleet. Truly a daring operation.