By Jonathan F. Keiler

On May 10, 1940, a daring group of German parachutists descended on the mighty Belgian fortress of Eben Emael, compelled its surrender, and opened the way for the German Army’s drive into Belgium.

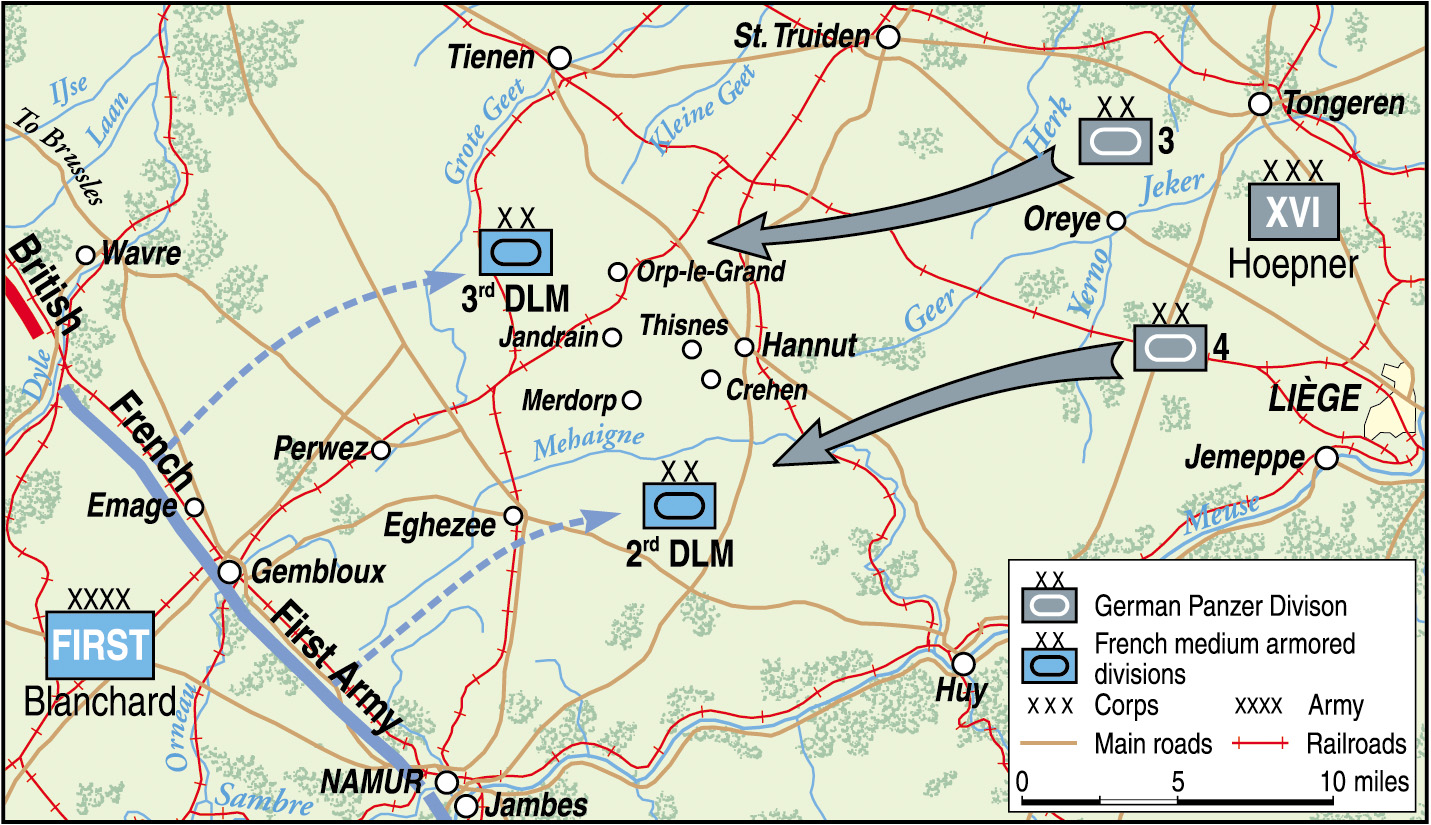

The French High Command believed Eben Emael would hold for a least five days, but now German forces poured into Belgium far earlier than anticipated. The crack XVI Corps, consisting of the veteran 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions, the 20th Motorized Division, and the 35th Infantry Division, led the German advance. The panzers drove straight for the Gembloux Gap, a traditional invasion route into northern France.

Named for the town of Gembloux, the gap encompassed an area of the east Belgian plain between the Dyle River and the Meuse/Sambre River system. This was flat, open country, well suited for the rapidly moving armored operations of the Germans. If all went according to the German plan, the XVI Corps would burst through the gap, wheel to the northwest, and join the rest of the German panzer forces in their drive to the Atlantic coast. The only thing that stood in the Germans’ way was the French First Army, now rushing into the vacuum left by Eben Emael’s sudden capitulation.

The Battle of Gembloux Gap involved one of the first major tank clashes in history, some of the hardest fighting during World War II and, in the end, did not quite turn out the way the Germans planned. In fact, the French First Army and its attached cavalry corps stopped the Germans cold. Had the French Army not collapsed to the south, the Battle of France might have ended on the smoking plain near Gembloux. How the French stopped the blitz-krieg at that small Belgian town is an often overlooked story of the war.

Sichelschnitt: The German Plan of Attack

The overall German plan for the invasion of France and the Low Countries is well known. The Germans’ main force, Army Group A, attacked through the Ardennes region toward the Meuse River with eight of Germany’s 11 panzer divisions. These troops surprised weaker French forces and drove to the northwest in the now famous Sichelschnitt, or cutting off, of other Allied armies in Belgium. Army Group C, without any panzer divisions, launched a holding attack to the south along the Maginot Line.

The third element of the German attack, Army Group B, hit the Allied armies in the Netherlands and Belgium. The mission of the latter was twofold: to draw Allied forces northward away from the main German effort, then to break and defeat them. The German Sixth Army, of which XVI Corps was the mobile striking element, met the French at Gembloux.

The XVI Corps was commanded by Lt. Gen. Erich Hoepner. It was the most maneuverable and powerful German force facing the Allies in Belgium. Hoepner’s two armored divisions, 3rd and 4th Panzer, consisted of roughly 700 tanks between them and were well supported by the Luftwaffe. Such a powerful force was not intended merely to draw the Allies away from the Ardennes. Hoepner intended to attack through the Gembloux Gap, defeat any Allied forces barring his way, and drive to the sea.

French Forces Hurriedly Assemble

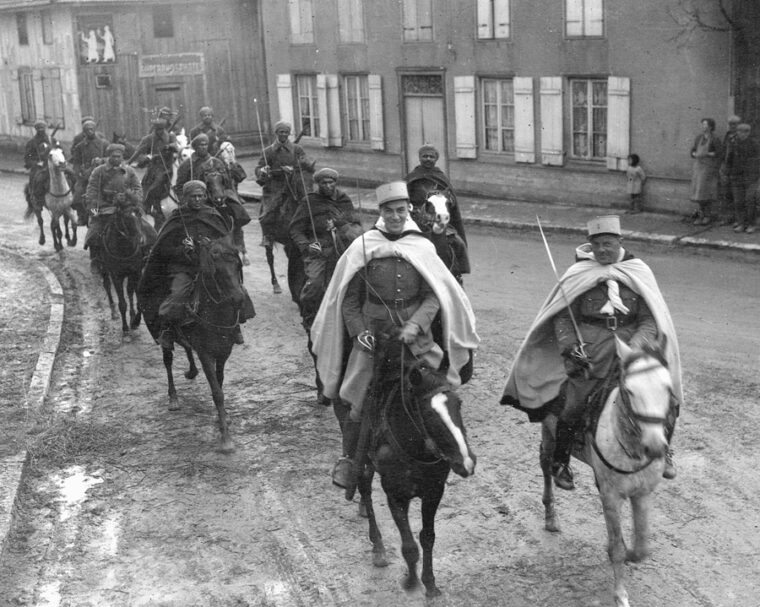

The first French force to arrive in the area was the Cavalry Corps, under General Rene Prioux, consisting of the 2nd and 3rd DLMs (medium-weight armored divisions). The French cavalry established hasty blocking positions in front of the Germans. The French First Army, comprised of the 2nd North African Division, the 1st Motorized Division, the Moroccan Division, and the 15th Motorized Division, followed the cavalry, establishing a line in the vicinity of the town of Gembloux.

All of the French units hurried into Belgium with the onset of the German invasion and the unexpected collapse of the Belgian border defenses. They arrived on the battlefield weary and needing rest, but as events determined, they would not get any. Prioux, expecting to find fighting and blocking positions for his armor prepared in advance by the Belgians, was dumbfounded when he discovered that almost nothing had been done. Footsore French infantrymen, expecting to move into prepared defensive positions around Gembloux itself, found they had to dig their own holes and lay their own obstacles straight off the march.

How the Opposing Armored Corps Were Organized

The XVI Corps advanced toward Gembloux with the two panzer divisions in the center, the 35th Division guarding the right flank, and the 20th Motorized on the left. On May 12, the 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions clashed with the advance elements of Prioux’s cavalry corps near the town of Hannut, half the distance between Eben Emael and Gembloux. It was one of the first major tank battles in history. The course of this fight was determined as much by the organization of the opposing armored corps as by strategy and tactics.

In 1940, each German panzer division had 300 to 400 tanks in its tables of organization, or about twice the number the divisions would have for the remainder of the war. These numbers, however, belied serious weaknesses within the organization. Most of the German tanks at this time were older models, Mark Is and Mark IIs, light tanks that were extremely weak in armor and armament. The Mark I carried nothing but a pair of machine guns, while the Mark II mounted a light 20mm cannon. In the 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions, these older vehicles accounted for nearly 90 percent of the tanks.

Only a couple dozen of the newer, more powerful Mark III and Mark IV medium tanks were available to XVI Corps. Alhough more effective than the lighter tanks, the Mark IIIs and IVs lacked formidable armor and armament as compared to corresponding French models. For example, the Wehrmacht insisted on equipping the Mark III with an obsolescent 37mm anti-tank gun because it was the same gun already used by the infantry. The Mark IV boasted a 75mm weapon, but it was a low-velocity gun designed for use against fixed targets and infantry, and was only marginally effective against enemy armor. By comparison, the French medium and heavy tanks carried a very effective high-velocity 47mm gun.

The German Armored Corps Advatanges

The Germans did have some advantages. All their tanks had radios. The tank turrets, at least in the Mark III and IV, were relatively large, and the German turret crews worked as efficient three-man teams, consisting of a loader, gunner, and tank commander. The traveling range of German tanks was no better than comparable French models, but unlike the French the Germans appreciated the logistical demands of mechanized warfare and thus were able to keep their tanks moving under the strain of battle.

In general, German armored divisions were better organized and operated with superior tactical and operational doctrines. The Germans made up for weaknesses by utilizing combined arms teams. Panzer divisions, motorized infantry divisions, and “light divisions” had somewhat differing tables of organization, but their various elements were largely interchangeable throughout the war. The excellent design and organization of these units enabled them to act and react flexibly, even to the point of mixing and exchanging divisional elements on the fly.

Reconnaissance troops, infantry, engineers, artillery, antiaircraft, and antitank units within the panzer divisions operated together to make the whole much more than the sum of its parts. Finally, at least in 1940, the German panzer divisions could count on operating with air support, including reconnaissance, air cover, and ground attack missions.

The French Weaknesses

On paper the French DLMs were a match for the panzer divisions, but obvious French strengths often hid severe liabilities. The greatest French weakness was leadership, particularly at the upper echelons of command, which would eventually undermine the entire Allied enterprise. Prioux, the cavalry corps leader, was a superior commander, and General Jean-Georges Maurice Blanchard, in charge of the French First Army, was also competent. Both were to perform well at Gembloux. French troops were ill-served by some of their weapons and much of their doctrine.

The DLMs were the middle-weights of an overly complex French armor organization. The French deployed and characterized their tanks as if they were 17th-century cavalry, and in many respects, the French expected their tank divisions to fulfill those roles. The lightest of the divisions, the DCLs, were equipped with armored cars and light tanks and expected to undertake traditional light cavalry duties such as reconnaissance, security, and screening. It was units of this type that were brushed aside by German armor in the Ardennes.

The heavy French tank divisions, DCRs, like Napoleonic cuirassiers, were kept in reserve, either for launching a crippling assault at the right moment or for delivering a decisive riposte to an enemy breakthrough. As befitting their status, the DCRs had the heaviest French armor. Prominent was the Char B, a tank much more heavily armed and armored than the German Mark IV. Like medium cavalry, Prioux’s DLMs were expected to function a bit like the other two types, depending on circumstance. They were equipped with light tanks and the medium Souma tank. All the French mechanized cavalry divisions had infantry and artillery components, but these forces were not as well integrated into the divisional organization as in a panzer division.

French tanks, like their divisional organizations, looked good on paper, but had fewer obvious weaknesses. French light tanks such as the plentiful H-35, carried low-velocity 37mm guns and were slightly better armored than their German counterparts. The Souma medium tank, the first tank to be manufactured with cast steel armor, had a more effective anti-tank gun (the 47mm) than either the Mark III or IV. The heavily armored Char B carried both a turreted 47mm gun and a hull-mounted 75mm cannon, much like the American Grant/Lee model tank.

All French tanks–incluing the medium Souma, and heavy Char B–had tiny one-man turrets. One-man turrets placed impossible demands on tank commanders in combat. These men had to function as vehicle commanders and serve, aim, and fire the turret gun. In the Char B, the driver had to drive and shoot the 75mm piece, while the commander handled the 47mm in the turret. Officers in command of platoons and companies were even more hard pressed than individual tank commanders. In modern terms, French tanks lacked sufficient memory and processing power. Most French tanks also lacked radios, forcing already harried commanders to use flags and hand-signals while exposed outside the turret. They were effectively inferior to German tanks in range and mobility due to weak logistic and maintenance support.

Lastly, the Germans had almost complete air superiority during the fighting in the Gembloux Gap. Allied fighters and reconnaissance aircraft made no more than occasional and ineffective appearances, and neither French nor British aircraft carried out ground support attacks against the Germans. The German Sixth Army, by contrast, was superbly supported by the Second Airfleet throughout the battle, and benefited in particular from the presence of hundreds of Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers which operated in close cooperation with the panzer divisions.

Tanks Against Tanks at Hannut

The light screening units of the opposing French and German armored divisions first skirmished near Hannut on May 12. French armored cars, accompanied in some cases by light 25mm antitank guns, fought German reconnaissance troops, also in armored cars or in motorcycle companies, which were equipped with 37mm antitank guns. Powerful German Kampfgruppen (battle groups) followed close behind the recon troops and drove the French back in hard but scattered battles amidst the picturesque Belgian countryside.

Although both the DLMs and panzer divisions had significant infantry forces with them, the opposing tank companies soon sought each other out in straight-up tank versus tank clashes. Here the differences in tank design and doctrine began to tell. The French tanks tended to move into fixed positions and then, like medieval knights, await their challengers. Relying on superior armor and cannons the French stayed in their static positions while the Germans maneuvered into the attack. As the battle progressed, large German combat teams flowed around the French positions, forcing French tanks to fight in ever smaller tactical units. Individual French tank commanders were certainly overwhelmed trying to communicate, acquire targets, and load and fire guns all at the same time. Yet, the French tankers were not faint of heart. Even when cut off from command because they lacked radios, and communication by hand signals and flags became increasingly problematic in the dust and smoke of battle, single isolated French tanks continued to fight.

The Germans took advantage of French disabilities. Operating under radio control on the ground and with air superiority, the Germans were able to maneuver around the less mobile French, hitting the French on the flanks and rear. German tankers noted that the fire coming at them from the R-35s and Soumas was often slow and inaccurate, which was inevitable with single-man turrets. This enabled the lighter German armor to close within effective range and take deliberate shots at vulnerable areas of the well-armored Soumas.

The tank battle, however, was not completely one sided. When the Souma’s 47mm hit a Panzer I or II, the result could be catastrophic. Even Mark IIIs and IVs could be destroyed or disabled by this highly effective weapon. As long as the French could hold their ground or withdraw before the Germans worked around their flanks, French tanks remained a deadly opponent. That is precisely what Prioux’s cavalry did.

For three days, May 12-14, the DLMs kept the Germans at bay, falling back onto the First Army’s hastily prepared defense around Gembloux and leaving behind the black, charred ruins of hundreds of French and German vehicles. The French were forced to abandon many functioning tanks for lack of fuel or repair.

The efficient Germans recovered and repaired their damaged vehicles, getting many back into combat and sustaining their fighting power, while the French cavalry withered. Exact losses are uncertain, but the French likely lost about 30 Soumas and twice as many H-35s, amounting to one-third of the DLM’s total strength. German losses were slightly heavier, perhaps amounting to 150 panzers, but the German tank force was larger and many repaired machines returned to service. However, Prioux had never intended to stop the Germans, only delay them, as his cavalry had done. For all of the suffering the panzers had endured in three days of steady combat, the Battle of Gembloux had only just begun.

French Artillery to the Rescue

The French were fond of saying that artillery conquers, infantry occupies. This reflected the importance the French attached to their artillery. In many places during that disastrous spring of 1940, it seemed as if French infantry could not even hold. This was not true at the Gembloux Gap. The French First Army contained the cream of the French infantry, well-equipped colonial troops, and motorized divisions, with plenty of artillery.

As the French infantry and artillery moved into position around Gembloux on May 13-14, their initial reaction was disappointment that the Belgians had not better prepared the vital ground for battle. In fact, the line the Belgians had prepared was to the east of Gembloux, around the area through which the cavalry corps had fought its delaying action. The Belgians, without coordinating the matter with the French, had set the line eastward, nearer the German border, in hope of sparing a greater part of the country.

Blanchard, the French First Army’s commander, ignored the Belgian dispositions and set his divisions along the Namur-Brussels railroad line. With its combination of steep embankments and causeways it provided a formidable tank obstacle. Deployed from the eastern outskirts of Gembloux to the Dyle River, which secured the First Army’s left flank, were the 15th Motorized, Moroccan, and 1st Motorized Division. The 2nd North African Division deployed on the west bank of the Dyle where it linked up with the British Expeditionary Force. Occupying Gembloux itself and a complex of small villages between Gembloux and the Dyle were the Moroccan Division and the 1st Motorized. These divisions, especially the Moroccans, would bear the brunt of the German attack.

The French established a defense in depth within Gembloux and the neighboring villages. They supplemented the rail-line obstacle with the few mines they possessed. Mostly, they fortified Gembloux and the adjoining villages with antitank guns, mortars, machine guns, and battalions of first-class infantry.

Following French doctrine, a tank battalion of 45 light R-35 tanks provided immediate support. A few batteries of 75mm guns were deployed forward as antitank guns. Behind the infantry were at least 60 artillery pieces per division, scores of additional heavy artillery pieces from corps and the French artillery reserve, and several batteries of field and anti-tank guns dropped off by the retreating DLMs.

The DLMs now formed the reserve, although some elements remained to harass the Germans from several villages just forward of the main French line. Finally, the French High Command attached 1st DCR, the premier French heavy tank division, to First Army as a counter to any German breakthrough. In total, the French defenses in the Gembloux Gap were more than a match for the oncoming and already battle-weary German panzer divisions and their supporting infantry.

Germans Stumble into Trouble

On the morning of May 14, despite the fact they had aerial reconnaissance, the 4th Panzer Division more or less stumbled onto the French line near the village of Ernage, located along the railway about three kilometers northwest of Gembloux. The Germans were clearly worn out by their engagement with the cavalry corps and evidently believed the French main line of resistance to be farther west.

Elements of the 7th Regiment of the Moroccan Division held Ernage in depth. A battery of 47mm antitank guns was deployed along the railway, supplemented by lighter but still effective 25mm guns. The 7th Regiment had mines, but they were unable to lay them before the Germans arrived. As they neared the French positions the Germans ran into concentrated artillery fire from the massed battalions directly behind the front.

Antitank guns fired into the panzers from the railway line, Ernage, and the neighboring hamlets. The German Mark I and II tanks were vulnerable to every French gun, from light 25mm antitank guns on the front line to the 155mm howitzers lobbing their shells over the French positions. Many panzers were damaged or destroyed as they attempted to cross the embankment and close with the enemy.

The German attack stalled and the panzers attempted to regroup beyond the railway line. French artillery bombardment chased the regrouping Germans, pouring shells into them, destroying vehicles, killing exposed infantrymen, and disrupting the German command. The 3rd Panzer moved to support the 4th on its right flank, but ran into the remaining tanks of the 3rd DLM and then got a taste of the massed artillery fire bedeviling the 4th. One German officer described the artillery fire before Gembloux as “annihilating.” (Veterans of the Great War could recall nothing worse and likely wished they were back in their trenches rather than on the exposed Belgian plain.)

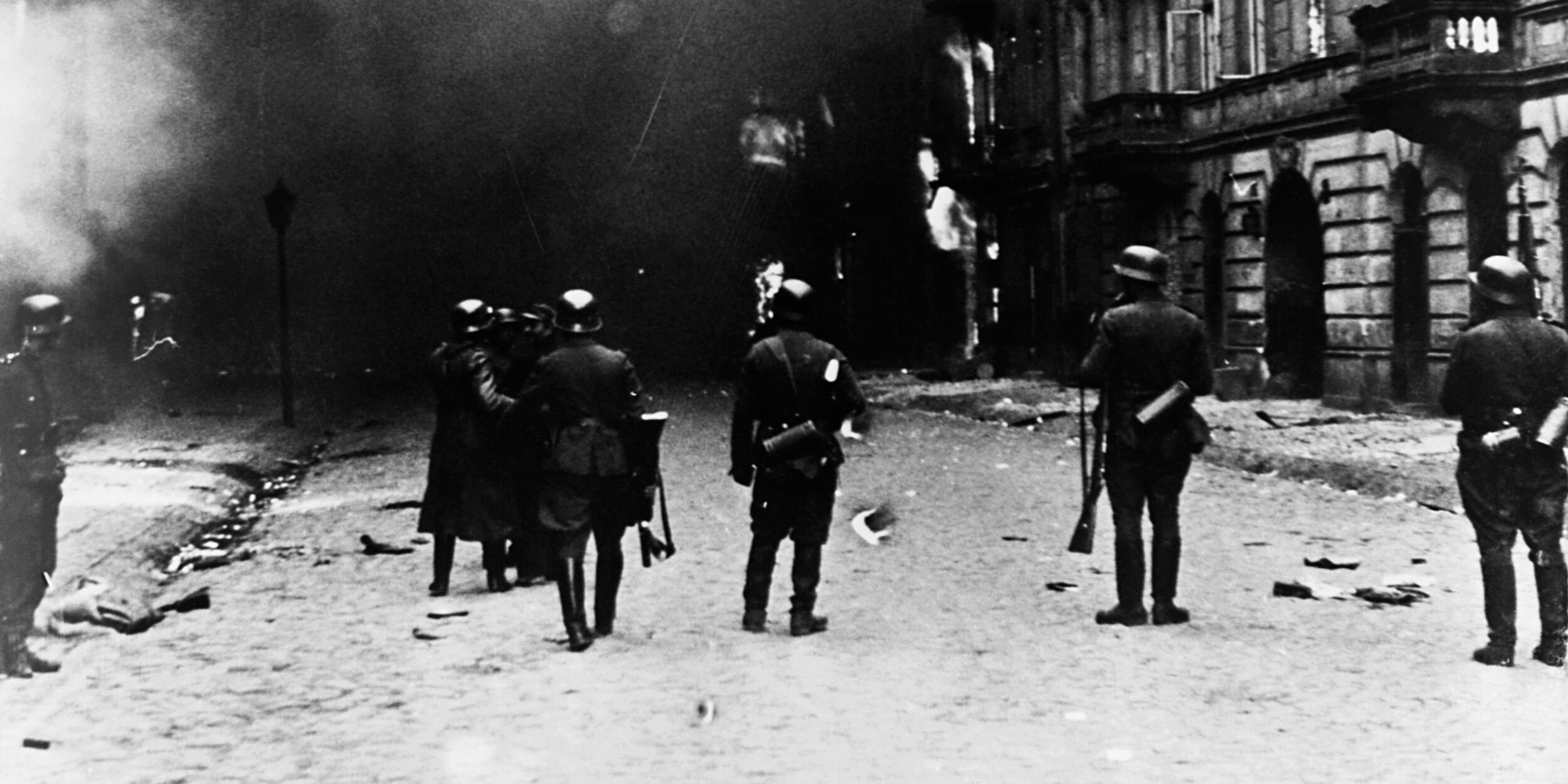

The Germans responded to the withering French fire by calling in the Luftwaffe. Waves of Stukas appeared overhead seeking out masked French batteries, bombing anything that moved or fired. Gembloux was set ablaze from German bombs. French guns were buried or overthrown by high explosives.

German infantry tried to infiltrate the French positions under the bombardment, hoping to pry out stubborn French troops and antitank teams and open the way for the panzers. The Germans found tough and stubborn French infantrymen, who fought with skill, bravery, and often fixed bayonets. Both sides took heavy casualties.

Occasionally, groups of panzers did manage to crack the forward French outposts but then found themselves counterattacked by French light tanks and ambushed by concealed anti-tank guns. Here and there, at great cost in men and machines, the Germans gained some footholds in the French line, but the main French position held firm throughout the fighting on the 14th. Once again, the Germans were forced to withdraw.

Throughout the night of May 14-15, French artillery continued to pound German assembly areas. Meanwhile, Hoepner, determined to match the unfolding successes of General Heinz Guderian’s panzers to the south and goaded by the Sixth Army’s commander, Walther von Reichenau, planned an all-or-nothing assault on the 15th, supported by reinforced Luftwaffe squadrons and XVI Corps’ own artillery, which had finally moved into position.

The Final Day of Fighting

The fighting on the 15th resembled that of the previous day but was even more intense. All the French divisions in the First Army’s line were drawn into the conflict as the German infantry divisions moved in to support the panzer divisions. German troops from the XVI Corps, along with the rest of the Sixth Army, attacked Allied positions from Gembloux to the Dyle River, where First Army’s left flank met the British Expeditionary Force.

The panzers and supporting infantry, backed by scores of screaming Stukas, clawed at the French positions. The French met every German advance with ferocious local counterattacks, sometimes with tanks, sometimes with infantry, but always supported by the ceaseless fire of French artillery. The Germans gained patches of ground, but failed to achieve a breakthrough.

At noon on May 15, the battle reached its crisis with the advanced elements of both armies near the breaking point and the battlefield itself saturated by concentrated artillery fire from hundreds of French and German guns, as well as heavy German bombs. Incredibly, the French line still held.

By late afternoon on the 15th, Hoepner had had enough and started to pull back his battered corps from the wrecked towns and villages that marked the extent of the German advance. Had the 1st DCR attacked at this point, the Germans might have been routed, but the French High Command had already withdrawn the powerful French armored division in a vain attempt to staunch the rupture of the line at Sedan. Not only that, but with the Germans in retreat before Gembloux the French First Army itself was ordered to withdraw as the French command began its panicky collapse in the face of the Sichelschnitt enveloping the beleaguered Ninth Army to the south.

Thus, the evening of May 15 saw both sides pulling back from the Gembloux Gap—the Germans because they had been beaten at that place, the French because they had been beaten elsewhere.

A Battle Overshadowed by Other Events

The Battle of Gembloux was immediately overshadowed by the general catastrophe that befell the Allies that May. The German XVI Corps, suddenly granted a reprieve, joined the German advance and no doubt preferred to forget the battle ever took place. The French divisions of the First Army, which fought so valiantly, fell back in relatively good order, fighting a delaying action against the now victorious Germans but ultimately allowing the British Expeditionary Force and thousands of French troops to escape at Dunkirk.

The result of these events was that the Battle of Gembloux itself has been almost lost to history and receives scant and often inaccurate coverage when mentioned at all. This was true in the months and years after the battle and largely remains true today. It is a pity, because Gembloux was the hardest fought and most savage battle of the entire campaign. Some historians assert that it demonstrated that the French infantry/artillery team was as good as the German tank/aircraft team, but the fundamental point is that it proved the blitzkrieg could be stopped by a combination of physical obstacles, defense in depth, determined infantry, mobile armored reserves, and effective antitank and artillery fire.

Yet it was not until the Battle of Kursk in 1943 when the Soviets defeated several fresh German panzer corps, that this was to be demonstrated again.The French and German troops that fought at Gembloux, including those thousands who fell there, knew the truth.

Jonathan F. Keiler left his law practice some years ago to teach high school in Bowie, Maryland. He is a veteran of the U.S. Army and last wrote for WWII History on the German effort to build an atomic bomb.

Thank you for telling the truth about the french courage during this battle of Hannut.

Thank you, I found this fascinating. If only…

I wonder as a Dutchman.

Why could Belgium hold back the Germans in 1940 eightteen days. In Netherlands: 5 days.

The Dutch government and Royal House went away immediately.

There could not be made a plan how to deal with the occupations which was to come.

The Belgian government had 13 days more for that.

In Belgium 40% of the Jews were murdered. In the Netherlands 70%.