By Terry Gore

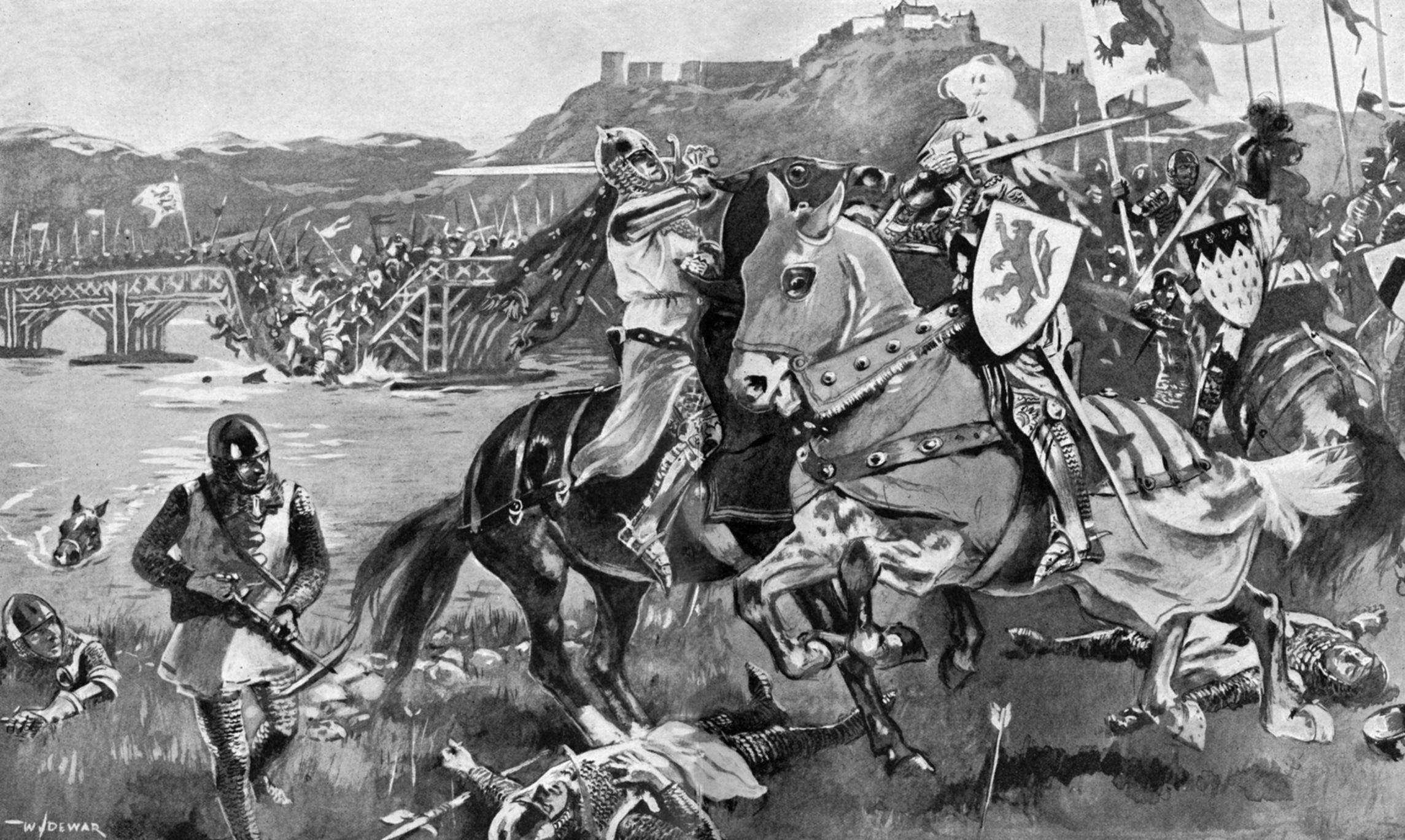

The English commander, William de Aumale, heard the roar of the Scots army even before it appeared out of the early morning mists. Thousands of semiclad Galwegians leading the Scottish attack raced toward the nervous Anglo-Norman army, closing the distance from 400 to 300 to 200 yards. De Aumale gave the command for the archers to fire. The air was suddenly filled with missiles as those Scots who carried shields took the first arrows on them, screaming their war cry, “Albion!” The English then began to use direct fire, shooting at the lower extremities of the howling Scots. With a moan, the first ranks fell apart under this fire. But the battle-hardened Scots leaped over their wounded and dying and continued to close on the frantically firing English. The Battle of the Standard had begun.

Henry I, the strong-willed son of William the Conqueror, died on December 1, 1135, leaving no legitimate male heir to follow him to the throne as the next king of England. His only legitimate son, William Atheling, had drowned in the sinking of the ill-fated White Ship in 1120. Henry was not without other sons; he had sired over 20 illegitimate children. But according to the chronicler, William of Malmsbury, Henry had called together all of his nobles, bishops, and abbots and had them swear an oath “[t]hat if he himself died without a male heir, they would immediately and without hesitation accept his daughter, Matilda, formerly Empress [of the Holy Roman Empire], as their lady. He said … that she alone had a legal claim to succeed him….” Matilda, widow of Geoffrey of Anjou, whom she had married 10 years before her father’s death, had three sons to succeed her to the throne of England.

Among the many nobles expected to support Henry’s choice of Matilda as ruler of England was Stephen of Blois, a third son of French nobility and nephew to Henry. Stephen had been brought up in Henry’s court, so he knew the Anglo-Norman aristocracy. Henry fully expected him to support Matilda, but in this he could not have been more wrong.

Stephen Disregarded His Oath of Fealty

Word of Henry’s death found Matilda deeply involved with a war in Normandy, while Stephen was on the Channel coast at Boulogne. He wasted no time in gathering his supporters and sailing to England to claim the throne by hereditary right. Stephen, by virtue of being the nephew of Henry as well as the grandson of William the Conqueror, declared himself the rightful heir to the throne. There is a very suspect justifying passage in the Gesta Stephani noting that on his deathbed Henry, “with very many standing by and listening to his truthful confession of his errors … very plainly showed repentance for the forcible imposition of his oath on the barons.” According to Henry of Huntingdon, Stephen, “disregarding his oath of fealty to King Henry’s daughter, tempted God by seizing the crown of England with the boldness and effrontery belonging to his character.” Actually, Stephen counted not only on the support of the English clergy, one of whom was his brother the Bishop of Winchester, but also of those Norman nobles who were unhappy with Matilda’s marriage into the House of Anjou, old enemies to Norman political ambitions.

Once in England, Stephen at first marched on Dover, but the garrison there under command of Robert Earl of Gloucester (one of Henry’s illegitimate sons) refused to allow him entrance. Receiving the same reception at Canterbury, Stephen then made his way to London where he was more warmly met. The Gesta Stephani noted that “[Stephen was] the man whom London, the capital of the whole kingdom, has received without opposition.”

When he later marched to Winchester, in effect taking control of the Treasury of England, Stephen suddenly found himself in a very good political position, in control of the purse. Claiming that Henry had in fact named him as his heir on his deathbed, the young nobleman was duly crowned in London by William, Archbishop of Canterbury, on December 22, 1135.

One by one, the nobles and clergy who had sworn fealty to Matilda switched their allegiance. It was a simple enough choice to make for many of the practical-minded Anglo-Normans. Stephen was there, backed by an army and the treasury, while Matilda was in Normandy, unable to gather her own forces together to challenge the self-proclaimed new king of England.

Some did not give in so quickly. Revolts against Stephen’s rule occurred in Wales, which, according to the Gesta, “breeds men of an animal type, naturally swift-footed, accustomed to war, volatile always in breaking their word … they made hostile raids in various directions, they cleared the villages by plunder, fire and sword, burnt the houses, slaughtered the men.” Stephen’s brother Baldwin had to take an army to put down the Welsh rebellion as well as insurgencies around London.

Revolts from Many Fronts

King David of Scotland, ostensibly in support of his niece Matilda, invaded northern England in 1136, only to meet with Stephen, backed by an army of his followers. David refused to swear fealty to Stephen, but his son Prince Henry did, receiving the earldom of Huntingdon for his pledge. (Later Henry swore loyalty to his father and fought with him in the summer of 1138.)

After Easter of 1136, more revolts broke out across England, but Stephen successfully dealt with each of them in turn, allowing himself a period of relative peace up until the third year of his reign, the fateful year of 1138. From that point on, Stephen’s kingship would be bitterly contested and peace would be but a memory.

David I had become king of Scotland in 1124, in his early forties, when his brother Alexander had died. David had been a younger son, like Stephen, without much prospect of prosperity, much less kingship, but fortune smiled on him. David had also spent many years of his young life at the court of Henry I. This had brought him into daily contact with many of the nobles of the court, an important consideration in his future plans. Upon his marriage in 1113 to the daughter of Waltheof, the Saxon earl of Northumbria, the Scottish nobleman found himself quite powerful in respect to land holdings and political influence.

In an interesting bit of diplomacy, David somehow convinced his brother, King Alexander, to let him rule the areas of Cumbria and Strathclyde as well as sections of Lothian. Once crowned king of the Scots, David is credited with bringing the feudal system to Scotland, as well as Anglo-Norman ideas and culture—although not without resistance from the Celtic Scots. In fact, a rebellion broke out in 1130 as Celtic forces rose in revolt, resulting in the rebels being soundly defeated at North Esk, and continuing even after until the leader of the revolt was betrayed by his own men and finally captured by David. The earldom of Moray was consequently forfeited to the crown and David parceled the lands out to his loyal followers, attracting Anglo-Norman knights and adventurers to his kingdom.

David’s political ambitions and military skill were soon to be put to the test as the Scots prepared to invade northern England, not for the quick but fleeting rewards of raiding, but in a quest for land to add to Scotland’s holdings. Stephen’s seizure of the English throne afforded David the necessary excuse to wage a just war against his southern neighbor. According to the Gesta Stephani, David, having “bound himself with an oath that on King Henry’s death he would recognize no one as his successor except his daughter or her heir, he was greatly vexed that Stephen had come to take the tiller of the kingdom of the English.” Whether this was but an excuse for the invasions of 1138 or an example of David’s actual moral fortitude are both arguable points. The invasions, however, were a very real threat to northern England.

Free License to Commit “The Most Savage and Cruel Deeds He Could Invent”

In January 1138, David’s nephew, William Fitz-Duncan, laid siege to the border town of Wark, a holding of the Norman noble Walter l’Espec. Ostensibly, David felt that northern England might have been ripe for revolt, but Stephen quickly preempted any such endeavor as he moved north in early February. It did not help that the Scots were brutal with the English. As the Gesta notes, “So King David … summoned all to arms, and giving them free license he commanded them to commit against the English, without pity, the most savage and cruel deeds he could invent.” How much of this is propaganda and rhetoric is impossible to say, but reports support the enmity and violence done by the invaders.

Stephen’s move north was not just to relieve the siege of Wark, but to check on the loyalties of his northern nobles and raid southern Scotland as well, showing his royal power and military abilities to one and all. The Scots sought to bring the English to battle on the northern bank of the Tweed River, but Stephen would not be drawn into such a poor position and instead marched through the lowlands, devastating the country as he went before finally running low on supplies.

After this, Stephen withdrew his army to Northampton to meet with his nobles over a troubling development. According to Hollinshed’s Chronicles Volume II, Matilda’s half-brother, the Earl of Gloucester, had taken advantage of the king’s absence to rise in open rebellion along with other nobles, causing Stephen to become “marvelously vexed.” This allowed David to invade northern England again. The Scots wasted little time, crossing the border in mid-April, capturing the Bishop of Durham’s castle at Norham. This convinced at least one powerful northern noble, Eustace Fitz-John, to join the Scots, turning over his castles to them. Here again we have a situation where a powerful army provided an expedient reason to switch loyalties from one faction to the other. Matilda had supporters, many of them sitting by, simply awaiting a reason or an excuse to declare for her.

In May 1138, Wark still remained in English hands. In fact, David was embarrassed when a sortie by the garrison managed to capture a Scottish supply train as it rode past the town. The Scots did have some good news, however, when a force of Scots and allied Galwegians (from Galloway in Scotland), led by King David’s nephew, Fitz-Duncan, defeated an Anglo-Norman force at Clitharoe on June 10. But David’s hopes of an uprising by the English in the north in support of him were quashed by the depravations commited by the invading Scots.

Mustering Up 26,000 Men

By July the Earl of Gloucester again raised the banner of rebellion in support of Matilda in England, and David saw his chance once more, King Stephen being involved in a growing civil war at home. Gathering his largest following yet, a reported 26,000 men—more likely 12,000-14,000—David marched south toward Durham, aiming to lay siege to it and then move into Yorkshire. His army, concentrating in late July, was made up of the Gaelic highland and Galwegian clans, lowlander spearmen, Islemen, Anglo-Norman rebels, sons of English families desiring to return to their homeland after self-imposed exile, and Eadgar Atheling, the Saxon exiled heir to the English throne.

Leaving the rebel Anglo-Norman Eustace Fitz-John in charge of the continuing siege of Wark, the Scottish army surged south. Many northern nobles were forced to make a choice between loyalty and pragmatism. If they supported the wrong side, they would lose their land as well as their titles and, at the moment, Stephen’s power seemed to be declining. Henry of Huntingdon (not the same man as King David’s son) noted that Norman knights comprised an important part of David’s army, no doubt proving that the proximity of the Scottish king and his army swayed many to join what they perceived as the winning side.

It fell to the aging Archbishop Thurstan of York to rally the Anglo-Normans in opposition to the Scots. At age 68, Thurstan, limited to riding in a litter, rallied the forces to fight the Scots. He was greatly aided by the Scots themselves. As Henry of Huntingdon related, the Scots “ripped open pregnant women, tossed children on the points of their spears, butchered priests at the altars, and, cutting off the heads from the images on crucifixes, placed them on the bodies of the slain.” According H.A. Cronne, a more recent writer, “the Scottish fury aroused the nearest thing to national resistance that 12th-century England saw—the old fighting spirit of the Anglo-Scandinavian north.”

Thurstan sought to go one step further. He would wage not just a military war of national defense, but a “holy war” against the hated ancient enemy. By appealing not only to their loyalty and honor, but also to their faith in God to right the wrongs brought about by the Scots upon the Church and its clergymen, Thurstan asked his countrymen to vow not to be bested by the “utter savages” from the north, those “breechless and barbarous Scots.”

One reference made by a monastic historian in the Chronicle of Man and the Sundreys describes the Galwegians, who made up a good portion of the Scots army, as: “That detestable army, more atrocious than pagans, reverencing neither God nor man, plundered the whole province of Northumberland, destroyed villages, burned towns, churches, and houses. They spared neither age nor sex, murdering infants in their cradles and other innocents at the breasts, with the mothers themselves, thrusting them through with their lances, or the points of their swords, and glutting themselves with the misery they inflicted.”

The Sheriff of Yorkshire, Walter l’Espec, described as a huge man with black hair and a flowing beard, “his eyes large and penetrating,” called out the English militia, or levy fyrd of Derby and Nottingham. Although fairly numerous, these levy foot were of uncertain value, especially when fighting the ravaging Scots, who were constantly at war with England or their neighboring clans. In any event, large numbers of them did flock to the support of their archbishop and sheriff, eager to avenge wrongs done to family and friends by the hated Galwegians.

Holy War

Other nobles also joined in the defense of the north, including William Peuerell of Nottingham, Robert Bruce, William de Percy, Walter and Gilbert de Lacy, and Ralph, the Bishop of Durham. Although involved with his own problems in the south, Stephen managed to send a small force north to assist the northerners in their struggle. Bernard de Balliol entered York with a body of knights in time to join in the plans being made to counter the Scottish invasion.

To add to the ecclesiastical spirit of the “holy war,” Thurstan and Ralph had a silver casket, carrying consecrated host, placed in a wagon that had a mast from which flew the banners of St. Peter of York, St. John of Beverley, and St. Wilfred of Ripon. This would be the rallying point of the English army, an object of religious significance that could not in any true Christian heart be allowed to be lost to the enemy.

The English levies, along with the nobles and their retinues of knights, mustered at York and by mid-August had determined to meet the Scots in open battle, a strategy urged by Thurstan. Although no official commander-in-chief was named, Ralph of Durham found himself selected as spiritual leader when Thurstan could not undertake the physical trials necessary to conduct a rigorous military campaign. William de Aumale and Walter l’Espec, being the most influential nobles present, gravitated to the military command of the army.

The English army began marching north from York to Thirsk astride the Scottish line of advance, and emissaries were sent ahead to meet with the Scots to negotiate. What the English leaders expected from this is uncertain, but it did buy time for reinforcements from Derby and Nottingham to arrive along with 124 knights and their retinues, swelling the English ranks.

Bernard de Balliol and Robert Bruce were the emissaries, and they met with David, who rejected their “logic” that he was actually leading the enemies of his people, the Galwegians, against his real allies and friends, the Anglo-Normans. They also offered the earldom of Northumbria to David’s son, Prince Henry, but David refused them. David and his son felt they owed no fealty to a king who had repudiated his own sworn allegiance to Matilda. Their loyalties and honor lay with their family and Scotland, not King Stephen. William Fitz-Duncan reportedly broke off the talks at that point and both English nobles renounced their friendship to David and returned to their army.

On August 21, English scouts brought word that the Scottish army was advancing down the Great North Road toward them. The Anglo-Normans subsequently planned to steal a night march on the Scots and attack them in a surprise assault at dawn on the 22nd. Advance elements of the Scottish army, perhaps having the same thoughts, blundered into the English army in the early morning fog, causing both forces to immediately fall into some kind of battle order, not easy in the best of situations, on two low hills, approximately 600 yards apart.

William de Aumale formed his army up on a low hill, with the wagon carrying the standards positioned in the very middle of his forces. This provided a convenient focus and, according to Richard of Hexham, “in doing this their hope was that our Lord Jesus Christ … might be their leader in the contest. They also provided for their men a certain and conspicuous rally-point.” Most of the knights and retainers were then ordered to dismount, their horses being sent to the rear along with a few hundred men who remained mounted to provide a mobile reserve. As Richard continues, “the greater part of the knights … became foot soldiers, a chosen body of whom, interspersed with archers, were arranged in the front rank” of the English army.

Shields Joined to Shields

Various reasons were given for why the English dismounted their knights (see sidebar). Richard of Hexham says they dismounted so the horses would not be panicked by the noise and shouting of the Scots. Aelred, abbot of Rievaulx, noted that the reason was so “that nobody could ride away,” while the noted historian C. Warren Hollister wrote that “Northallerton was almost Hastings in reverse,” where the Saxon influence on the tactics of the Normans, i.e, dismounting in a static defense, could now be used along with archer fire to disrupt and thwart an enemy attack.

As the English army formed into battle lines, the dismounted knights were placed in the front ranks, with the levies, both bow- and spear-armed, placed behind them. As Aelred noted, “The most vigorous knights [were] placed on the front line, so inserted spearmen and archers that, protected by the arms of the knights … shields were joined to shields.” Leaders de Aumale and l’Espec, along with a number of knights, were stationed around the wagon bearing the standards in case the Scots did manage to break through on the highest point of the hill they occupied.

There is an interesting anecdote about the battle. According to one source, Thurstan had sent some of the English with instruments called petronces, or large horns, into caves underneath the field of battle. These instruments produced such a fearful noise that David, sending herds of animals against the English to break up their ranks, instead found these same beasts turning in panic and disrupting his own lines. Since none of the other sources mention this, it is probably just a bit of folklore, though nothing can be totally discounted!

Ralph, as spiritual leader of the English and speaking for Thurstan, then absolved any who fell in this battle from their earthly sins, as Pope Urban had absolved the Crusaders who marched to Jerusalem 40 years before. He then spoke to the dismounted knights formed up in the front of the army. “Normans … no one ever withstood you…. [The Scots] have neither military skill, nor order in fighting, nor self command. There is, therefore, no reason to fear. They do not cover themselves with armor … [while] your head is covered with the helmet, your breast with a coat of mail, your legs with greaves, and your whole body with a shield…. What have we to fear in attacking the naked bodies of men who know not the use of armor? Is it their numbers? Numbers, without discipline, [hinder] success in the attack…. But I close … as I perceive them rushing on, and I am delighted they are advancing in disorder.”

Wanting the Honor of Leading the Attack, the Galwegians Refused to be in the Rear

Indeed, David’s impetuous Galwegian allies were already surging through the dissipating morning mists, howling their war cries. The Scottish king had formulated a different plan of battle, but it had quickly gone awry. Initially, David hoped to emulate the Norman tactics of William the Conqueror at Hastings, using his small number of archers to open gaps in the English ranks through which his knights would ride, destroying the English order and routing the uneasy levies. He also may have given thought to dismounting his own knights, using them with his archers to open a hole in the English ranks through which the Galwegians and Highlanders would attack.

Needless to say, the battle plan could not be implemented because the Galwegians refused to be left in the rear, away from the “honor” of leading the attack. One chieftain proclaimed, “Why trust to the goodwill of these Frenchmen [the knights]? None of them, for all his mail, will go so far to the front as I, who fight unarmoured in today’s battle.” Declaring that armor was “an impediment rather than a protection,” and that they, not the knights, had won at the Battle at Clitharoe, the Galwegians were entitled to lead the attack. An Anglo-Norman rebel knight challenged the Galwegian chieftain for these statements and David, hoping to keep his army from self-destructing and knowing the fierce resolve of the Galwegian chieftains Donald and Ulgerich, reluctantly acceded to their demands.

As the Scottish army formed up into its respective divisions, David assigned his various leaders their commands. He would remain with the center and the reserves, flying his banner, the Dragon Standard of Wessex. His son, Prince Henry, would command the heavy cavalry, numbering only 200 men according to Florence of Worcester, as well as most of the archers. Fitz-Duncan would ostensibly be in command of the first lines of Galwegians, though they would obey their own local leaders before an Anglo-Norman noble.

As the Galwegians charged, David hoped they would at least clear some lanes through which his impetuous, frenzied troops could force their way into the enemy lines. The Chronicle tells us that at the first clash, the Galwegian “men of Lothian” attacked the English lines “with a cloud of darts [javelins] and their long spears,” while the English “archers mingled with the knights, pierced the unarmored Scots with a cloud of arrows.” The Scots did, in fact, cause the English levies to waver, but the dismounted Anglo-Norman knights held their ranks. The English archers fired volleys of arrows into the struggling Galwegians. Aelred noted that the unarmored Scots “[looked] like hedgehogs with the shafts still sticking in their bodies.”

Robert Bruce, apparently visible to the Scots where he stood in the English array, was loudly taunted as a traitor by David’s knights. The Galwegians charged once more, this time pushing back the English lines, causing consternation in their ranks, but once again the dismounted knights held, cutting down their unarmored foe.

Curiously, the bulk of the Scottish army apparently did little but sit and watch as their allies were slowly decimated. Then one commander saw his chance to make a difference. Prince Henry, timing his attack, suddenly ordered his 200 heavy cavalry and the infantry under his command to attack the English left flank. The cavalry very quickly outstripped their foot supports and smashed into the English lines. Fierce fighting found the heavy cavalry cutting right through the English ranks, but losing much of their strength in the furious hand-to-hand combat.

Chivalry Over Victory?

The knights managed to cut their way through the English, but instead of heading toward the standards and trying to capture them, which would probably have caused a major blow to morale among the thousands of English levies, Henry led his attack against the English horse, behind the army, fully expecting his foot supports to follow him and complete his rout of the English left. Unfortunately for the Scots, the dismounted English knights had closed their ranks up again as soon as the enemy heavy cavalry had broken through and so stopped the Scottish foot cold. Henry of Huntingdon, instead of turning his remaining cavalry and hitting the wavering English in the rear, led his knights against the Anglo-Norman mounted reserve, chasing off the horses of the dismounted knights, but letting his small force be destroyed in the process. Here is a prime example of the early knightly code of fighting a “worthy opponent” when one was available, rather than choosing the militarily sound alternative in order to win the battle.

At this point, the battle was still anyone’s to win. As Prince Henry’s knights fought and died, an Englishmen picked up a head from the bloody ground and proclaimed it to be King David’s. A groan went up from the Scottish ranks as the rumor spread, forcing David to ride out to the front and show himself to his men.

It was then, Henry of Huntingdon tells us, that “the chief of the [Galwegians] fell, pierced by an arrow, and all his followers were put to flight.” Actually, both Donald and Ulgerich had been killed, causing the Galwegians to flee the field.

At this point, David, seeing the Galwegians streaming from the field, ordered his reserves into action. He even dismounted to lead the attack on foot, but this did nothing to rally the faltering Scottish morale—the rout of the Galwegians spread to the other clans and contingents. As the Highlanders watched their allies flee past them, they turned and joined in the retreat. The king then drew his remaining forces and bodyguard together and fell back to the hill from whence they had started the battle less than an hour before. He managed to rally enough of his men around his banner to dissuade the English from attacking his strong position.

A Bitter Loss for the Scots, but How Bad?

After another hour or two of desultory combat, King David, fearing his son was dead, began to withdraw his remaining men back toward Scotland. The jubilant English praised God and proceeded to hunt down wounded and straggling Scots.

The battle was a bitter loss for the Scots. Contemporary estimates put the casualties at 10,000 to 12,000 Scottish dead, certainly a hugely inflated number. Because the Scots were able to maintain their operations in the north of England even after their losses, perhaps a more realistic estimate would be 1,500 Galwegians, and 1,500 to 3,000 others killed or captured. English losses were perhaps 500 to 1,000 in total. The Scottish retreat from the battle was not without its own drama—the Lowlanders and Highlanders fought against each other as they fled the field, each accusing the other of being traitors and cowards.

Of the heavy cavalry, the Scots counted a total of 19 left with Prince Henry, miraculously escaping the English thanks to his dispersal of the English horses. The prince and his surviving men mingled with the English until they could make their escape and rejoin King David three days later.

As with many battles of the medieval period, the results were not what one would expect. In 1139, the Treaty of Durham found King Stephen ceding Northumbria to David and recognizing the sovereign rights of Scotland, the point being to settle the political situation in the north. He had his hands full with Matilda’s growing support in England during a period that would become known as The Anarchy, which gives some idea of its severity and effect on the psyche of the chroniclers of the time. King David outlived his son Prince Henry by a year, dying peaceably 15 years after the Battle of the Standard. King Stephen died a year later, in 1154, leaving the throne of England to Matilda’s eldest son, King Henry II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments