By Roy Morris Jr.

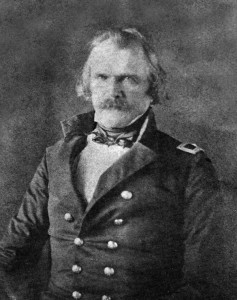

Confederate President Jefferson Davis considered his old West Point classmate Albert Sidney Johnston “the greatest soldier, the ablest man, civil or military, Confederate or Union, then living,” and it is safe to say that no other general in either army began the Civil War with a more glittering—or fleeting—reputation.

High Expectations

The towering expectations surrounding Johnston’s Civil War service began even before he joined his first command. As a transplanted Texan, Johnston chose to stick by his adopted state when it seceded in February 1861. Resigning his post as commanding general of the Department of the Pacific two months later, Johnston headed east to meet with Davis in Richmond, Va. Breathless news reports of Johnston’s progress followed him every step of the way, and he was greeted as a hero before he ever set foot in the capital.

Inevitably, perhaps, Johnston could not meet the sky-high expectations. Amid all the hoopla, one salient fact was overlooked—Johnston had never commanded an army of his own. To make matters worse, he was given an assignment that even the most experienced of generals would have found daunting. With less than 50,000 troops at his disposal, Johnston was tasked with defending a 500-mile-long border stretching from eastern Kentucky to western Missouri—an area equal in size to western Europe. Complicating his task was the fact that three major rivers wound their way through his defenses, at the mercy of industrious Union gunboats.

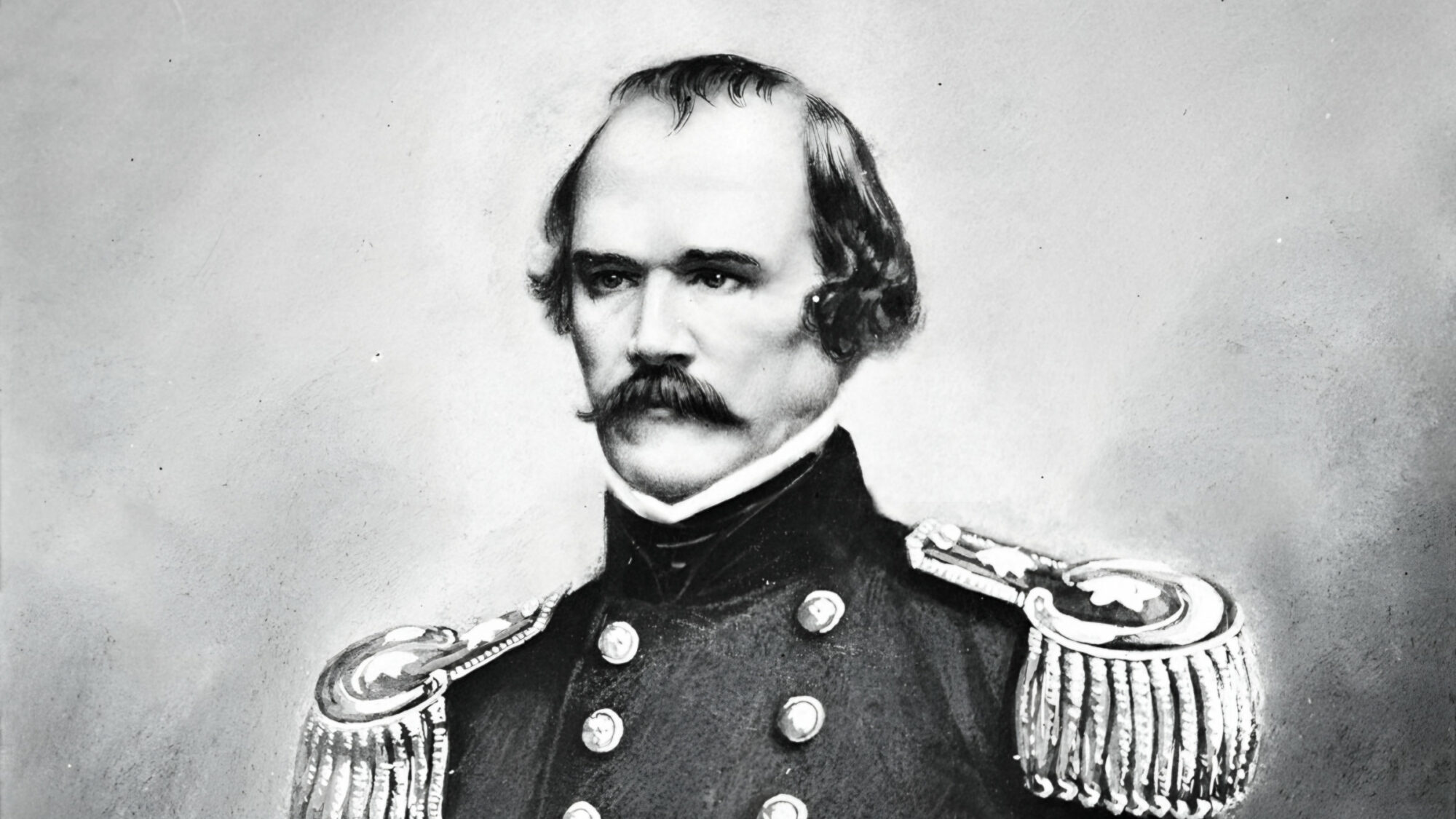

It was sure-fire recipe for disaster, and Johnston was not long in adding to his own cup of woe by failing to adequately safeguard the Confederate strongpoints at Forts Henry and Donelson. In February 1862, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant easily captured both forts, along with 12,000 Confederate troops. That feat set Grant on the way to becoming the North’s leading commander, and put two large dints in Johnston’s previously spotless suit of armor. Still, his old friend Davis continued to support him. Responding to one Confederate congressman’s complaint that Johnston was “no general,” the president tartly replied, “If Sidney Johnston is not a general, the Confederacy has none to give you.” He angrily refused to remove Johnston from command.

“We Must Use the Bayonet”

Besides, Johnston had a plan for recovering both his reputation and the territory he had lost. Massing his army at Corinth, Miss., he organized a counterattack on Grant’s Union forces encamped around Shiloh Church in southwest Tennessee. On the morning of April 6, 1862, Johnston prepared to lead his army into battle. Picking up a tin cup, he sportively clinked his men’s bayonets. “These will do the work,” he assured them. “We must use the bayonet.” He added, for whatever it was worth, “I will lead you.” Earlier, he had rejected worries that the Union forces were too numerous to attack. “I will fight them if they were a million,” he asserted.

As it was, he did not fight them for long. Sitting astride his horse, Johnston suddenly reeled in the saddle and fell into the arms of Tennessee Governor Isham Harris–on hand that day as a civilian aide. “General, are you hurt?” cried Harris. “Yes, and I fear seriously,” Johnston replied.

Unnoticed in the heat of battle, Johnston had been struck behind the right knee by a Union bullet. Ignoring the wound, the general continued directing the battle while his boot filled with blood. The bullet had severed his femoral artery, and Johnston bled to death in a matter of minutes.

Ulysses S. Grant later rendered his own verdict on his slain opponent. “I do not question the personal courage of General Johnston, or his ability,” Grant wrote in his Personal Memoirs. “But he did not win the distinction predicted for him by many of his friends. He did prove that as a general he was over-estimated.” It was a verdict that Johnston did not live long enough to appeal.

What do Johnson, Lee and Grant all have in common? None of them had ever commanded an army before. What else do they have in common? They all began with significant failures. Grant at Belmont, Lee in West Virginia and Johnson at the abovementioned Fts Henry and Donaldson.

Johnson followed his initial failure with the brilliant Shiloh campaign. First he achieved total strategic surprise, approaching within gunshot of his opponent in total secrecy. His initial attack was an absolute tactical achievement. And lacking the magic bullet finding him amid the chaos of the battlefield, there is every reason to believe that he could and would have been hands on, not allowing the battle to stagnate, allowing Grant the time to reconstitute his shattered army and arrange for new Union troops to join him for the second days battle.