By James E. Held

For General Washington and his Continental Army the situation had become desperate. The ink had hardly dried on the Declaration of Independence when 30 British warships and 400 transports under Admiral Lord Richard Howe sailed unchallenged past the Sandy Hook lighthouse to the Tory stronghold of Staten Island. “I thought all London was afloat,” exclaimed an astonished Maryland private at this forest of masts and rigging carrying 32,000 troops, the “largest and best-equipped [British] expeditionary force” ever assembled. Richard Howe’s landlubber brother General William Howe commanded the English regulars and German mercenaries poised to capture this mercantile and maritime hub that John Adams called a “key to the whole continent.”

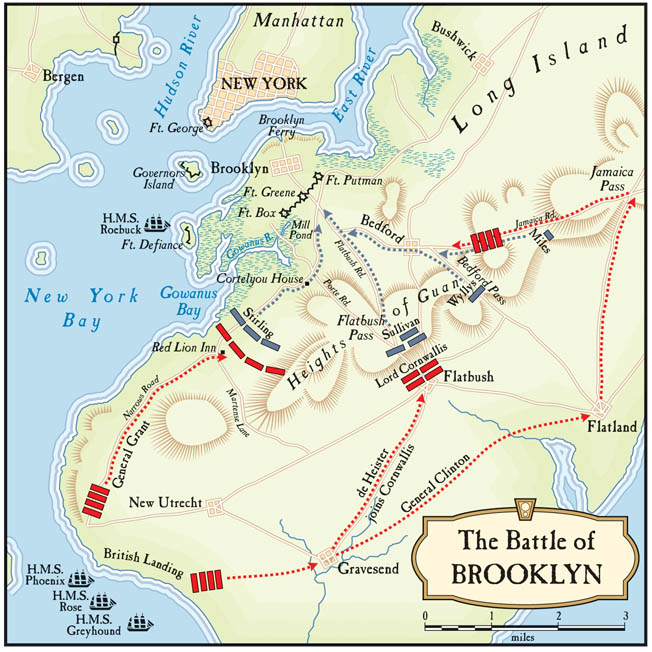

To defend New York City, Washington led the largest American army of the war: 23,000 troops from eight states ranging from the well-armed and disciplined Maryland and Delaware regiments to inexperienced, ill-equipped, and untrained militia. Elite or green, every man was needed to counter the English threat; with New York in enemy hands, the broad Hudson River would become their nautical highway northward to join with British mobilization in Canada. Once the two pincers severed the colonies they could finish off rebellious New Englanders and the fractious Middle Atlantic colonies like dinner courses. Now, however, all that campaigning might prove unnecessary; a brilliant British move on the night of August 27, 1776 worked to snare Washington’s army in a classic roll-up-the-flank maneuver and threatened the entire Revolution with annihilation.

Normally only market-bound farmers and sots stumbling from rural taverns traveled at night along colonial Brooklyn’s rough dirt roads. On this evening, though, 10,000 British dragoons, Highlanders, grenadiers, light infantry, and artillery left their campfires flickering deceptively at the beaches of Gravesend, Long Island, for a swift and silent nocturnal march through the ruts and mud of King’s Highway. General Howe wanted no repeat of the bloodshed that won his controversial victory on Boston’s Bunker Hill. Instead of brutal frontal assaults, this brainstorm of subordinate General Henry Clinton planned to surprise defenders at Jamaica Pass, then fight its way through and around American positions along the Prospect Heights. Still, one shout from a startled farmer or picket would betray their movement to the nearby Continentals who, if attacked, could easily shatter this thin red line stretched two miles.

“17,000 of the Best Troops of Europe Met 5,500 Undisciplined Men”

When five mounted American scouts challenged the English vanguard at Jamaica Pass their capture and interrogation revealed to an astonished General Howe that the way was open. Although expecting an ambush at any moment, the Redcoats arrived unscathed in Bedford Village at 9 in the morning to find its redoubt undefended. Their cannon fire signaled to the English center and left already engaging the American line that their advance westward down Jamaica Road had begun.

As historian Thomas Flint wrote, “17,000 of the best troops of Europe met 5,500 undisciplined men,” and in three hours it was over. In the debacle, almost 2,000 Americans were killed or captured. Washington, watching from the corner of modern Court Street and Atlantic Avenue, exclaimed, “Good God! What brave fellows I must this day lose.” But as the stampeding Americans streamed across the marshy Gowanus River, a haughty Scottish officer scorned: “Multitudes … of [American] infantrymen … drowned and suffocated in morasses—a proper punishment for all Rebels…. Our losses were nothing [and] the Hessians and our brave highlanders gave no quarters … and put all to death that fell into their hands.”

The bulk of the American troops escaped to Brooklyn Heights, which Washington had reinforced by ferrying troops from New York. Then General Howe, haunted by the ghosts of Bunker Hill, restrained the assault and ordered siege equipment brought up until favorable winds carried his ships up the East River to tighten the noose around Washington’s neck.

The British advance on New York surprised no one. Biding their time, the city’s Loyalists waited for the King’s forces to return, as all knew they would attempt to do. New York was too valuable a prize to ignore; this superb harbor not only offered refuge for British naval and merchant vessels but also formed the mouth of the mighty Hudson River. Powerful ships-of-the-line could easily sail north with flood tides and favorable winds to Albany, and Native American, French, and English traders in canoes or sturdy bateaux knew that short portages to Lake Champlain gave access to the St. Lawrence River. America’s invasion of its northern neighbor had stalled at the walls of Quebec City. The counterthrust by its defender, General Sir Guy Carleton, had driven the Continental Army from Canada, and now he prepared an offensive southward as he built a fleet on this inland sea of Lake Champlain, Lake George, and the Hudson River.

Jay Proposed That the Army Burn the City to the Ground and Retreat

During the summer of 1776, while the Continental Congress penned, debated, and passed the Declaration of Independence, American troops, cocky and confident after victories at Boston and Newport, marched to New York. That February, General Charles Lee arrived to prepare its defenses, but after a month’s activity, forces under British General Henry Clinton threatened Charleston, SC, and allowed pause in the work of Washington’s most experienced commander. Lee’s correspondence revealed, however, that he hardly missed the burden of defending the untenable: “I am like a dog in a dancing school—I know not where to turn myself…. The circumstances of [New York], intersected by navigable rivers, the uncertainty of the enemy’s designs and motions, who can fly in an instant to any spot where they choose with their canvass wings…. I can only act from surmise and have a very good chance of surmising wrong.” New York delegate John Jay even proposed to the Continental Congress that the army burn the city and retreat upriver to West Point.

Still, the English massing that summer off Staten Island could afford neither failure like that of the March retreat from Boston nor the political consequences of a Pyrrhic victory. The Colonials still retained their own parliamentarian partisans who considered this entire conflict pointless. George III had also given the Howe brothers the dual role of military commanders and “peace commissioners,” empowered with both carrot and stick to entice or drive the errant colonies back into the English fold. As Whigs, they disagreed with the harsh retribution inflicted after rebellions in Ireland and Scotland. Their older brother George had died fighting the French in the American wilderness, so William and Richard Howe sincerely hoped for reconciliation with their New World brethren. So far, offers of “a free and general pardon” and attempts to parlay with Washington had come to naught. Now, they felt, a superior English Army would force a “decisive Action, than which nothing is more to be desired … [than] the most effectual Means to terminate this expensive War.”

Achieving that victory was Howe’s dilemma; the long approach of a direct amphibious assault on New York would betray the maneuver to American defenders, but New Jersey’s rivers, cliffs, and swamps hampered a decisive flanking maneuver. The remaining prospect was landing on the sandy beaches of Long Island and attacking New York from the east. British artillery, if positioned on Brooklyn Heights, could intimidate or pulverize the city that clung to the lower three miles of Manhattan Island. But a steep glacial moraine called the Prospect Range blocked the way. Its precipitous, thickly wooded slopes confined the passage of wagons bound for the village of Brooklyn or enemy forces on the offensive to four narrow passes named Gowanus (running along the shoreline), Flatbush, Bedford, and, another five miles eastward, Jamaica.

The Heavy-Drinking, Hard-Working Scot

Lee had trenches dug, planted batteries along the Manhattan waterfront, and posted sentries at Kings Bridge over the Harlem River, the city’s sole land link with Westchester County and Connecticut. His departure south on March 9 left a heavy-drinking, hard-working Scot in charge. General William Alexander, a veteran of the French and Indian War, insisted on being addressed as the very unrevolutionary “Lord Stirling” in deference to his lapsed royal title.

By April when General Israel Putnam arrived to assume command, Manhattan’s defenses were far advanced, with “each street leading from the water blocked by barricades,” and the earthworks and fortresses extending to New Jersey and Governors Island at the foot of Manhattan. Engineers sank wrecks in the Narrows, stretched log booms across the Hudson, and planned to extend another 2,100 feet of chain to bar the enemy fleet. Near the end of April, Putnam sent energetic General Nathanael Greene across the East River to fortify Long Island and the bucolic burg of Brooklyn with its thousand inhabitants, mainly of Dutch ancestry, and their black slaves. Greene studied and inspected the roads, trails, landmarks, and knolls from Hellgate to Gravesend. On the highest point of the Heights he built a redoubt with seven guns to command the East River entrance. In the valley stretching between the Gowanus and Wallabout Bays, soldiers, slaves, and civilians constructed a series of forts dubbed Putnam, Ring, Greene, and Box, linked by breastworks along the meandering tidal river named Gowanus.

General Putnam, with his credo, “Cover Americans to their chins and they will fight until doomsday,” expected another static, defensive Bunker Hill-style engagement with British frontal assaults on their fortified and formidable positions. Washington, who arrived on April 13, had prudently established a “flying camp” of 10,000 men who were ready to respond to any threat, but with the obstacles and expanse of the local geography, his manpower was still too meager to match the immense battlefield dimensions.

General Lee best expressed the American predicament: “What to do with this city, I own it puzzles me. It is so encircled with deep navigable water, that whoever commands the sea must command the town.” The Continentals had no fleet, and the formidable rivers that flowed around these islands gave the British ships mobility while severely hampering American maneuverability. Still, Lee felt storming the defensive works surrounding New York “might cost the enemy many thousands of men.” But any fortress is as strong as its defenders, and frankly they did not impress their commander.

Haunted by the Specter of Oliver Cromwell

American history glorifies Minutemen as brave artisans and yeomen who at a moment’s notice left hearth and plow to defend liberty. In reality, militia fought dismally except when defense of their homes strengthened their resolve. The Continental Congress could not comprehend that declaring independence also meant organizing a force capable of winning it. Washington pleaded that the cause was lost “if the defense is left to any but a permanent standing army,” but Congress remained haunted by its own specter of Oliver Cromwell.

As ardent students of history, our Founding Fathers knew all previous republics had fallen to dictators, including England’s own experiment. General Cromwell, after defeating the Royalist forces of Charles I in Britain’s Civil War, dismissed the wrangling Parliament in 1653 to rule himself. A standing army, many believed, would only be the muscle for an American generalissimo to seize dictatorial authority. They preferred military power dispersed among individual states and cities, so Washington’s army in New York fell under 13 jurisdictions whose regional rivalries and short enlistments hamstrung him from fielding an effective and cohesive force.

At Boston, the exasperated commander found state regimental strengths varied from 600 to 1,000. Soldiers accustomed to electing their own officers refused to accept unfamiliar appointees or simply returned home. Washington railed that “Connecticut wants no Massachusetts man in their corps; Massachusetts thinks there is no necessity for a Rhode Islander to be introduced.”

Ever the aristocrat, Washington found his troops “an exceedingly dirty and nasty people” who showed “such a dearth of public spirit, and such want of virtue, such stock-jobbing, and fertility in all the low arts to obtain advantages of one kind or another … I never saw before, and pray God’s mercy I may never be witness to again…. Could I have foreseen what I have, and am like to experience, no consideration upon earth should have induced me to accept this command.” But, the problems of commanding such motley, undisciplined rabble surrounding Boston paled before besieged New York.

If the streets of this city with 25,000 inhabitants were lined with “buildings lofty and elegant,” Yankee Colonel Loammi Baldwin wrote, “the manner of the people differ … having Jewish, Dutch and Irish customs.” Those same inhabitants continued trading with the enemy; entire militia units defected while Continental soldiers neglected camp sanitation; and drunkenness was all too common. When news of the Declaration of Independence arrived, mobs that ripped George III’s statue from its pedestal roamed the streets to settle personal differences with prominent Tories. Loyalist plots both alleged and genuine led to the arrest of Mayor David Matthews and the hanging of one of Washington’s bodyguards, Thomas Hickey, whose execution drew thousands of spectators, among them the city’s prostitutes.

Country lads and village yokels here to fight felt unbridled from hometown Calvinist and Puritan strictures when sirens beckoned from the Gomorrah called “the holy ground.” Baldwin wrote his wife that “these bitch-foxly jades, jills, haggs, sturms, [and] … whores continue their employ which is become very lucrative.” As duty officer, he “broke up the knots of men and women fighting, pulling caps, swearing, [and] hurried them off to the Provost Dungeon by half dozens.” Venereal disease joined the other camp ailments of fever and dysentery.

The Troubles of a “Dirty Mercenary Spirit”

Logistical shortages also led to the plundering of houses, trees, and gardens while even firewood ran short. Work on fortifications progressed, but a significant portion of the American force did not have muskets and instead armed themselves with 12-foot spears. When English vessels challenged the gauntlet of forts and batteries on July 11, half of the Continental gunners were either intoxicated or off whoring. What Rebel shots were fired fell well short of the ships Phoenix and Rose, which would disrupt American supply lines upriver on the Hudson, and six Continentals were killed when drunken artillerymen set off an explosion. Washington lamented, “Such a dirty mercenary spirit pervades the whole that I should not be at all surprised at any disaster that may happen.” Happen it did.

Too late, Washington realized the August 22 British landing at Gravesend Bay and Denyse Ferry (modern Fort Hamilton) was no feint. The rich Long Island landscape offered not only supplies for an army unleashed to fight after shipboard confinement, but this pattern of fields and woods was also their terrain, not the dense forests of the American wilderness. It was far closer in character to European battlefields where the British could wage well-honed tactics. Commanders Washington, Putnam, Greene, Heath, Lord Stirling, Sullivan, Parsons, and Spencer formed a fraternity of frontier fighters who could field or foil savage guerrilla skirmishes, but now they faced 17,000 of the world’s most formidable army in the open field.

As American riflemen burned wheat fields and buildings, dispersed livestock, and harassed and skirmished with the enemy bridgehead on Long Island, barges all the while landed British artillery and reinforcements from Staten Island. Hessian soldiers, following the withdrawing Continentals, found small packages of tobacco wrapped in paper messages that urged them in German to desert to the American side, but their officers warned them to expect no quarter from the Rebels. Typhus untimely confined Nathanael Greene to a sickbed, so on August 23 Washington gave Greene’s command to John Sullivan, a man he found capable, but his “over-desire of being popular, … leads him into some embarrassments.” Although totally unfamiliar with Long Island’s terrain, Putnam received overall command. Perhaps overconfident with a string of forts along the Gowanus Valley, he neglected Washington’s orders to construct abatis, traps, and ambuscades to strengthen the line along the Prospect Heights.

Even today, these steep slopes in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park become veritable jungles in summer. Topography and laurel thickets had to funnel the major assaults through the passes. Still, both Lord Stirling on the American right and Sullivan commanding the center felt concern about the neglect of Jamaica Pass. Pickets from a Pennsylvania regiment under Colonel Samuel Miles stood watch only by day and withdrew at night. Washington, citing lack of fodder, dismissed 400 mounted Connecticut volunteer cavalrymen who, though offering to pay for their own pasturage, refused to dismount and fight as foot soldiers. Stirling and Sullivan personally paid a squad of horsemen who had patrolled the pass for five uneventful nights. The British, however, lacked neither mounted mobility nor intelligence of the American line. General Henry Clinton, eager to revenge his defeat at Charleston, discovered with the aid of Loyalist scouts that complacency had descended on Jamaica Pass, the American Achilles’ heel.

Merchants and Farmers Prepared to Meet the British Army

As 10,000 British troops made their nocturnal march along King’s Highway, the first shots resounded about 11 pm at Redcoats raiding watermelons near the Red Lion Tavern. Their blundering played perfectly into the British ruse of the main thrust coming down the Shore Road. By 1 in the morning, the English under General Grant advanced noisily, and the alarm reached General Putnam. As tensions rose with the sun on that August 27, Americans fought for the first time as an independent nation against professional soldiers with cavalry, concentrations of cannon, and formations of colorful Redcoats bearing gleaming and lethal bayonets. With the morning’s “Red and angry Glare” these merchants, tailors, shoemakers, barbers, and farmers were about to feel the full fury of the British Army.

Lord Stirling welcomed two regiments from Delaware and Maryland as well as the 400-man reinforcements from Sullivan—half of his strength—to bolster the American right wing to 2,300. Survivors said Stirling “gave battle in the true English taste” and his ranks did not waver through musket volleys, even as “balls and shells [of British artillery] … now and then [took] off a head.” Although firing constantly, British General Grant made no concentrated effort to attack Stirling. Colonel Samuel Atlee’s Pennsylvanian infantry drove a party of Redcoats from a nearby hill, but the English ranks did not advance; neither did the Hessians and the 42nd Highlanders under General Leopold de Heister who shelled the makeshift breastworks of felled trees that Sullivan’s troops had erected on the American center.

Washington, crossing the East River, felt relieved that the adversarial winds prevented English ships from supporting the attack, and for inspiration he gave this rousing speech: “The time has come when Americans must be freemen or slaves. Quit yourselves like men, like soldiers, for all that is worth living for is at stake.” He also threatened: “If I see any man turn his back today, I will shoot him through.”

Hearing the fighting at Flatbush Pass, Colonel Samuel Miles and his Pennsylvanians had left Bedford Village and marched westward until Colonel Samuel Wyllys and his 22nd Connecticut Regiment, who were guarding Bedford Pass, recommended they go back to their post. Returning, Miles discovered to his “great mortification” the British baggage train of Clinton’s 17th Light Dragoons, Cornwallis with the First Brigade of Grenadiers, two regiments of infantry, the 71st Highlanders, and Howe with the Guards and three brigades of infantry. This massive advance guard had passed unnoticed by Miles, and he tried to send word to alert Sullivan of the impending encirclement that had trapped his own men. Dispersing into small bands, his soldiers cowered or crawled through the underbrush in hopes of reaching the safety of the American line.

Many Were Shot or Stabbed While Attempting to Surrender

Once Wyllys heard the firing to the east he and his men retreated from Bedford Pass without firing or receiving a shot. With Howe’s cannon signal, de Heister’s Hessians and Highlanders fired one last volley before charging up Flatbush Road. Green-coated Jaegers, with their short-barreled carbines, usurped American guerrilla tactics and flanked through the forests where Hessian officer Colonel von Herringen saw American “riflemen … pierced with the bayonet to the trees.” Sullivan sorely missed the reinforcements sent earlier to Lord Stirling, and his cannon and rifles were deprived of their full effect by the thick foliage and the road’s winding character. Four hundred hard-pressed Continentals were forced back to discover English cavalry and light infantrymen blocking their retreat. One British officer conceded, “The Americans fought bravely and could not be broken till greatly outnumbered and taken flank, front and rear.” Sullivan and 60 men flushed from a cornfield surrendered with their flag bearing the word “Liberty,” but many stragglers and wounded caught in the woods and clearings were shot or bayoneted while attempting to submit.

Washington could only watch from the Ponkiesberg Hill as his outer defenses crumbled, but Stirling stubbornly held open the window of escape. Meanwhile, the British fleet anchored nearby restocked Grant’s depleted ammunition and reinforced him with another 2,000 Royal Marines. Grant, who had boasted to Parliament that he could march through America with only 5,000 Regulars, now had 9,000 men against “the only formation of American organized resistance.” The Pennsylvania Militia under Hand and Atlee had taken cover under trees nearest the shoreline while on Stirling’s left a Maryland detachment covered his main force on Blockje’s Hill to form an inverted “V.” With a small stream flowing below the high ground they held, their position was excellent and his men refused to be goaded into wasting their volleys until the British came within close range. The Maryland uniforms proved so polished and impeccable that 20 unwary Royal Marines mistook them for Hessians and approached close enough to be captured. It was not their dress, however, but the valor of this regiment that made the greatest impression on both friend and foe.

As the flanks of British, Hessian, and Highlanders converged, they soon would outnumber Stirling by almost 20 to 1. Lord Cornwallis’s seizure of the Vechte-Cortelyou house, a fieldstone structure in Stirling’s rear, completed the envelopment that threatened annihilation of the entire American right wing. Leaving General Parsons in command of the withdrawal, Stirling, with Scottish bravado and 400 men from Maryland, attacked 2,000 British backed with artillery before they could effectively fortify the sturdy 17th-century dwelling. Six times they charged, twice driving the enemy from the stone house, but with each wave the attackers diminished in numbers. These suicidal assaults had no hope of success other than to buy time for the rest of the Americans to escape, and costs were dear: The regiment lost 350 of 400 men, killed or captured, including Lord Stirling himself. He chose to surrender to the German de Heister rather than the Englishman Cornwallis, who nevertheless exclaimed, “General Lord Stirling fought like a wolf.”

“They Came Out of the Water and Mud to Us, Looking Like Water Rats”

By noon, the last mopping-up operation on Battle Hill, in modern Greenwood Cemetery, was almost complete, and Hessian Colonel von Herringen exclaimed, “It looked horrible in the wood, as at least two thousand killed and wounded lay there.” As the Continentals streamed across the Gowanus River into Brooklyn, a 15-year-old Connecticut private in Brooklyn remembered, “When they came out of the water and mud to us, looking like water rats, it was a truly pitiful sight.”

British casualties were 349, including 61 dead, a fraction of what the heroic Maryland men suffered, but all sides received an unexpected respite when General Howe did not press the attack against Brooklyn’s fortified line.

General Clinton, who had spotted the weak American defenses along Jamaica Road, expressed understated fury. “His excellency, who … saw [the American] confusion might be tempted to order us to march directly forward down the road to the ferry, by which if we succeeded, everything on the island must have been ours.” Seizing the landing would have trapped the Americans, so the astounded if relieved General Putnam likewise remarked, “Howe is either our friend or no general.”

The Americans, however, were once again “covered to their chins.” Reinforcements had strengthened Brooklyn Heights, and British troops were running solely on adrenaline—Grant’s troops had fought for over 10 hours, and the main column under Howe, Clinton, and Cornwallis had endured an exhausting forced march as well as heavy combat. A British officer wrote, “We had not fascines [bundles of branches] to fill ditches, no axes to cut abatis, and no scaling ladders to assault so respectable a work,” which British engineers later found solidly and well built.

History judges William Howe as a lax and lethargic general, more ardent in romance than battle. More graciously, as a gentleman of the old school, he sought humanity amid the brutality of warfare and felt genuine concern for his soldiers, who after the battle were scattered, hungry, and exhausted. No reserves remained, and the wounded and over 800 prisoners required attention. Although rabid German Jaegers clawed at the American abatis, Howe restrained them. He felt that certainly this example of British invincibility and magnanimity would bring the Rebels to their senses, and with the inevitable shift of wind, the fleet would move into position up the East River, bagging the lot. Meanwhile, work progressed on siege works that via trenches and mortars would soften American fortifications before storms of infantry ran up to seize them. More ardent subalterns, however, such as Captain George Collier on the frigate Rainbow, felt the urgent need for action: “If we become masters of this body of rebels the war is at an end.”

Hard Biscuits, Cold Pickled Pork, No Sleep

Washington felt none of Howe’s graciousness but rather the burden of an ominous choice between his army and the city that duty and strategy required he hold. The loss of Brooklyn Heights would make New York practically untenable, so he strengthened its defense to over 9,000 men. Time, however, was the English ally, and already on the 28th they completed a redoubt east of Fort Putnam and continued digging trenches and bringing up artillery. Infantry probed and tested the strength of the American lines. Then two days of torrential rains and thunderstorms would turn the trenches into a muddy gruel and soak clothing, cooking fires, powder, and spirits. Troops unsheltered from the elements found sleep impossible and their sustenance consisted solely of hard biscuits and cold pickled pork. Even the strong northeast winds that barred the East River approach to the British fleet chilled the waterlogged soldiers to the bone.

After closely inspecting the state of defenses and the exhausted defenders, Pennsylvania General Thomas Mifflin told Washington that the line could not possibly hold against a concentrated assault. Besides the encroaching siege works, British anchored nine miles away in Pelham Bay threatened King’s Bridge, the sole escape route off Manhattan. Six of seven generals in the Council of War held on August 29 urged immediate withdrawal, and Washington was finally convinced that only with the army intact did New York have any hope.

Meanwhile, the world’s best navy eagerly awaited orders to test the Continental batteries along the East River. This mile-wide estuary channels the powerful ebbs and flows between Long Island Sound and New York harbor. Strong and treacherous tidal currents churn through the rocks and shoals of Hellgate, and until Robert Fulton’s development of the steamboat, only the callused hands and Herculean strength of local ferrymen plied this water that changes hourly from still to surging. The only men to match these ferrymen’s skill and stamina were Marblehead fishermen and Salem seamen plucked from the trenches “with sailor-like cheer and despatch[sic]” to man the thwarts and muffle their creaking rowlocks with cloth.

Washington cloaked the retreat as making “room for … newcomers” so “a proportionate number of regiments” were to be relieved or shifted. At 7 o’clock in the evening of August 29, his troops were ordered to assemble at their camps with rifles and gear and to wait for orders. That morning, every craft “from Hellgate on the Sound to Spuyten Duyvil Creek that could be kept afloat and that had either sails or oars” had been commandeered and brought to Brooklyn. General Mifflin volunteered to command the rear guard, and the withdrawal began at 8 that night under Brig. Gen. McDougall, who expressed extreme pessimism about the entire operation. Well might he have been discouraged early on: While the best troops had the dubious honor of holding the trenches, McDougall dealt with the incoming columns of discouraged and undisciplined dregs.

The Mob of Soldiers Were Crazed with Fear

On the East River banks, baggage, ammunition, and artillery disembarked first for New York. The ranks, although ordered not to speak or even cough, began reacting to the threat of British ships looming out of the darkness between them and safety. Colonel Israel Hand saw “frightful disorder” growing at the ferry, with “the mob of soldiers, maddened by fear … crowding the declivity from Sands Street to the water.” Colonel Fish, one of Washington’s aides, lifted a stone above his head and threatened to sink an overloaded boat and its unruly, panicking soldiers unless order was restored. Some groups tried climbing over the shoulders and heads of those in front, but other regiments were not infected with contagious panic and disembarked in disciplined order.

Observing the withdrawal, a Tory matron Mrs. Rapalie, dispatched her black slave to warn the British of the retreats. Luckily for the Americans, the German troops he located found his colonial Brooklyn accent incomprehensible and held him instead as a spy.

Sheets of rain falling with the freshening northeast wind may have muffled the noise of the evacuation, but it also prevented use of the sloops and sailboats needed to complete the monumental task. Rowboats, flatboats, whaleboats, and pettiaugers propelled by oars made hard progress, but then the fortune that had favored the British shifted with the southeast wind to the American side. From this direction, Brooklyn Heights gave a snug lee, the water flattened, and the entire flotilla could get to work, often loading men and equipment to only inches of freeboard. Back and forth these vessels traveled, with some Marblehead men, 10 and more trips back and forth.

By 10 o’clock that night more and more relieved troops stumbled onto Manhattan shores, and the rear guard of Pennsylvanians, Connecticut, Delaware, and remnants of the Marylanders and New Yorkers, including 150 grenadiers armed with grenades, felt their ranks thinning. When a regiment pulled out, soldiers right and left moved to fill the gaps. But when the line became too lean, troops were forced to concentrate in the forts and leave dangerous vacancies.

At 2 in the morning, aide-de-camp Alexander Scammell mistakenly told General Mifflin and his rear guard to withdraw, and Washington was aghast to see him at the ferry landing. “It’s a dreadful mistake,” he said. “There’s such confusion at the ferry that we’ll be cut to pieces if you don’t get your men in the lines before the enemy occupies them.” Without hesitation, they returned to the front. Later, Colonel Chester and his men were likewise ordered by mistake to retreat, but before reaching the ferry they were sent back to the trenches again. With dawn’s illumination growing brighter, these steadfast soldiers felt their chances of escape dimming, until forces apparently meteorological, but seemingly divine, intervened.

Connecticut Major Tallmadge wrote that “a very dense fog began to rise and it seemed to settle in a peculiar manner over both encampments. I recollect this peculiar providential occurrence perfectly well, and so very dense was the atmosphere that I could scarcely discern a man at six yards’ distance.” Colonel Smallwood thanked the haze, for “otherwise the fear, disorder and confusion of some of the … troops” would have left them cut off. Finally, the rear guard, hidden in heavy mists from the observation of enemy pickets, left the trenches for the boats.

“In the History of Warfare, I Do Not Recollect a More Fortunate Retreat”

British suspicions were not aroused until 7 in the morning, and not confirmed until 8:30 when General Robertson led a party into the empty fortifications. Washington, who had hardly been off his horse or slept for the past 48 hours, was among the last to leave. The English found only some heavy artillery sunk to the axles in riverbank mud and a mere three stragglers who lingered to pillage the baggage.

Major Tallmadge, also among the last to leave, tied his horse to a post at the ferry landing. When he and his men reached New York, the fog was still so thick that he asked permission of Washington to retrieve his favorite steed. The general, also an avid equestrian, gave permission. Tallmadge commandeered a boat, found some daring volunteers to return to Brooklyn, and coaxed his horse aboard. The party had just rowed back out of reach as the first British troops appeared. “We were saluted merrily from their musketry, and finally by their field-pieces,” Major Tallmadge recorded. Once safe with his mount on the New York side he also reflected, “In the History of warfare, I do not recollect a more fortunate retreat.”

Washington, however, was not through retreating yet. After three weeks of fruitless negotiations on Staten Island with Ben Franklin, John Adams, and Edward Rutledge, Howe routed the American militia at Kips Bay along New York’s East River banks. The defeat at White Plains followed, then on November 16, 1776, came the bitter loss of Fort Washington on the Hudson shore with 3,000 men, supplies, and artillery. After desertions and expired enlistments, Washington’s Grand Armée dissipated on the December retreat across New Jersey to the Delaware River. Only 4,000 men of the original 23,000 he began with in the defense of New York City remained to achieve his stunning and desperate victories at Trenton and Princeton.

“The Declaration of Independence that was signed in ink in Philadelphia was signed in blood in … Brooklyn,” wrote John Gallagher in his 1995 Battle of Brooklyn 1776. With estimations of American losses running between 1,200 and 3,000 out of a total of 50,000 participants, its casualties are not surpassed by any other battle of the war, but the Revolution’s largest conflict remains among its most overlooked. Its few inconspicuous monuments are ignored amid modern Brooklyn’s bustle, even though numbers of soldiers at heralded Yorktown totaled only 19,000 participants for both sides.

The Power of Becoming Invincible

Albeit a defeat, the Battle of Brooklyn is arguably the Revolution’s most significant for the Americans because “the Father of Our Nation” learned his lessons well. Washington realized the British had become too canny to offer another Bunker Hill-style engagement, so mobility, not stationary fortifications, remained the advantage that the dimensions of North America offered. The only campaign to wage against what historian John Gallagher called the world’s “best fighting machine” was one of flexibility and constant maneuvering. “We should on all occasions avoid a general action or put anything to the risk unless compelled by a necessity into which we ought never be drawn,” Washington wrote. An American attack came only when the British were weak or divided. With the English supply lines stretching across an ocean, the war became one of attrition and endurance, one where retreat on this vast landscape was not dishonorable. Another vital lesson was learned by Congress: A confederation of militia was not going to get the job done—the effort for independence was going to need a standing professional army, the Continental Army.

If wars, as Winston Churchill claimed after Dunkirk, “are not won by evacuations,” nevertheless they do not necessarily lose them. For the Americans, years of retreats, fierce fighting, and hardship lay ahead, but at the news of the Brooklyn disaster Abigail Adams wrote a letter to her husband John expressing the spirit that ultimately gave America victory: “If we should be defeated … we shall not be conquered. A people fired, like the Romans, with love of their country and of liberty, a zeal for the public good, and a noble emulation of glory, will not be disheartened or dispirited by a succession of unfortunate events…. May we learn by defeat the power of becoming invincible.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments