By Roy Morris Jr.

“Every war will astonish you,” American general Dwight D. Eisenhower said after World War II. As the leader of the Allied forces that successfully landed on D-Day and marched into Berlin 11 months later, Eisenhower obviously knew what he was talking about. The American political leaders at the beginning of the Civil War were less prepared, or less willing, to expect the unexpected. Long decades of increasingly vitriolic arguments between the northern and southern regions of the country, revolving mainly around the issue of slavery and its expansion into newly acquired territories, had accustomed both politicians and the public to angry words and empty threats.

Following his election as president in November 1860, Abraham Lincoln professed to be unworried about rumors of impending secession. “The hot breath of secession,” Lincoln told his secretary, John Nicolay, “is just the trick by which the South breaks down every Northern man.” He did not intend to be similarly intimidated by the “political fiends” he saw at work in the South.

Not for the last time would Lincoln prove to be disastrously wrong about the deadly earnest intentions of alienated southerners. When a longtime observer of his high-string southern neighbors, Cincinnati journalist Donn Piatt, warned the president-elect of the looming danger, Lincoln airily responded, “Well, we won’t jump that ditch until we come to it.” And to another supporter, Lincoln advised, “Entertain no proposition for a compromise in regard to the extension of slavery. The tug has to come & better now than later. Concessions on our part would be fatal.”

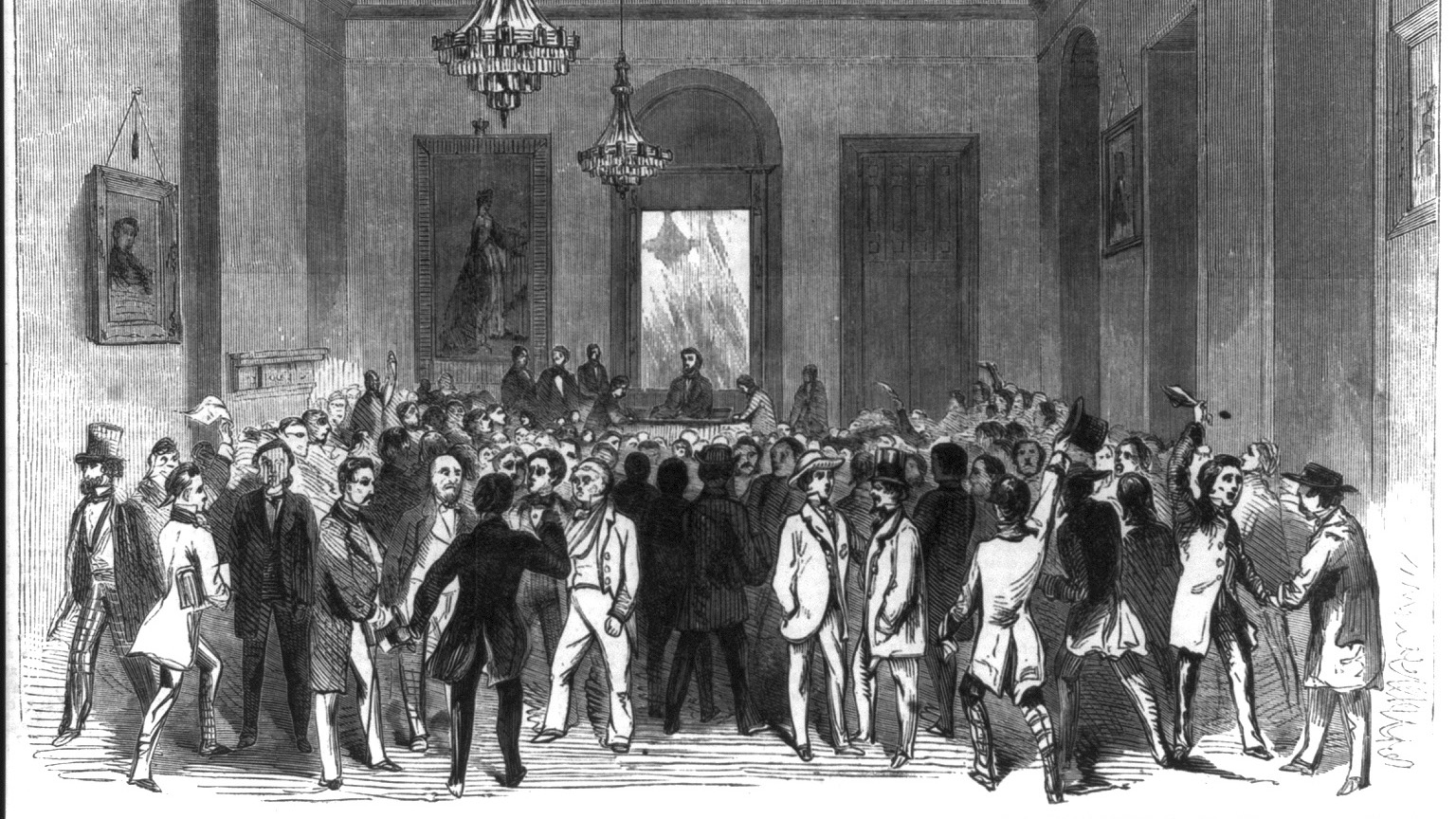

Fort Sumter & The Point of No Return

Soon, the “tug” would indeed come, in the form of the Union installation, Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor. When impatient, overconfident Confederate forces fired on the fortification in the early morning hours of April 12-13 1861, the long war of words instantly became a war of bombs and bullets and bayonets. Before long, Lincoln would be saying, in one of the homely frontier aphorisms to which he was addicted, “The bottom is out of the tub.”

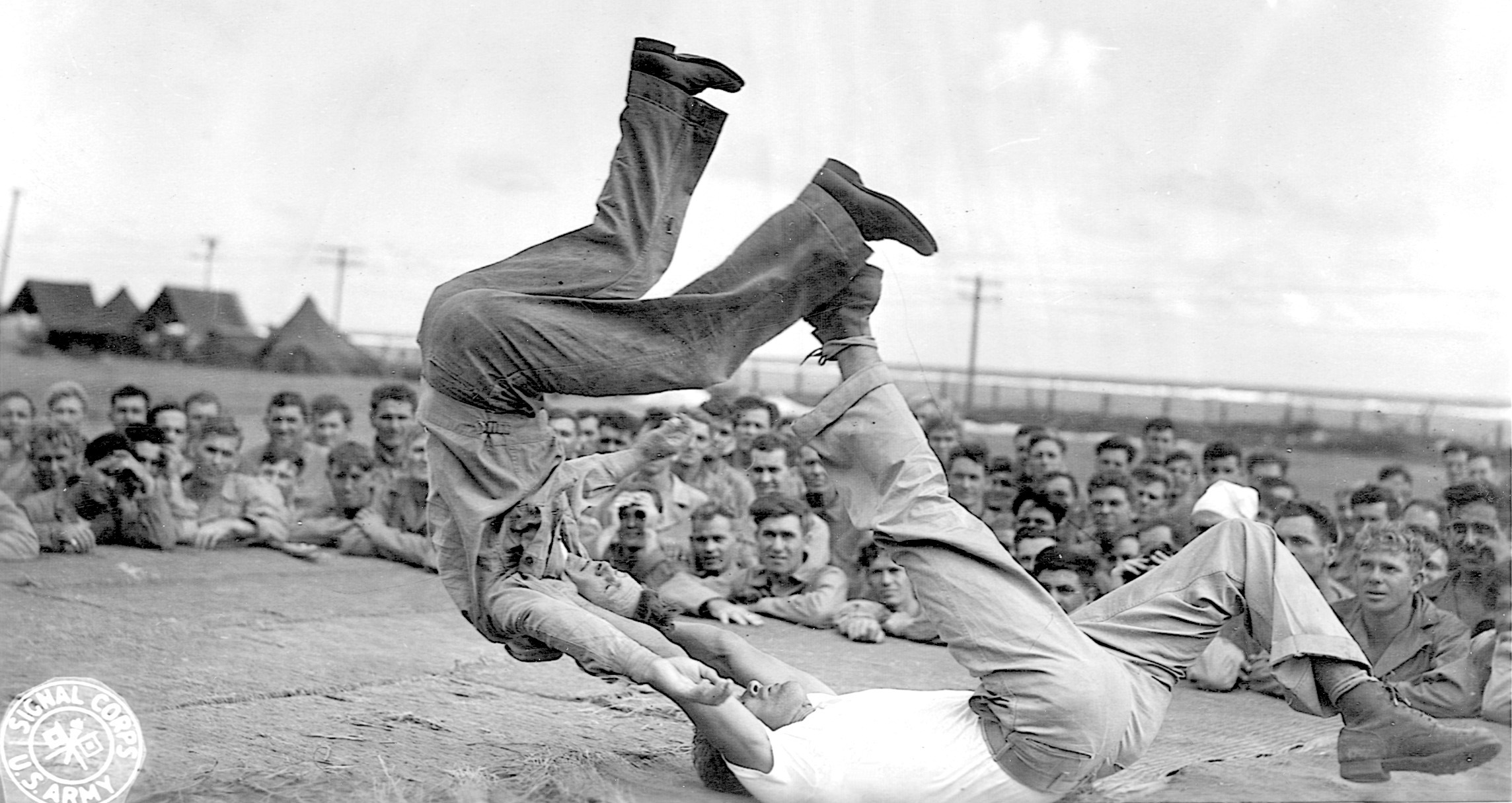

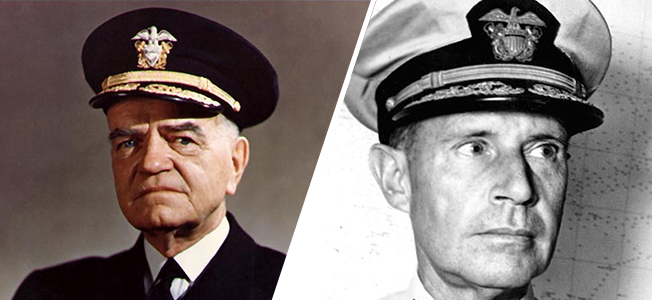

The first year of the Civil War was primarily one of trial and error. The two sides struggled to raise armies, appoint commanders, and feel out each other’s military intentions. The major opening battles—Manassas, Wilson’s Creek and Ball’s Bluff—were hard fought but poorly led contests between citizen-soldiers who had not yet learned the deadly skills they would develop soon enough—or else die trying. Still, there were some generals on either side who understood from the start the brutal enterprise into which the two regions had blundered. Stonewall jackson at Manassas and Ulysses S. Grant at Belmont knew more clearly than most that the developing war would be neither short nor bloodless. Both men, significantly, had received their baptism of fire during the Mexican War, when they had fought on the same side. Now they were enemies.

Another future Civil War leader, a frontier-born southerner who unlike Jackson and Grant had not enjoyed the advantage of a West Point education, would put the water into suitably stark context. “War means fighting, and fighting means killing,” Nathan Bedford Forrest would say. Having learned that lesson—up close and personal—in several deadly hand-to-hand duels before the Civil War, Forrest knew whereof he spoke. It was then, and remains today, an enduring pity that few politicians in the North or South shared that cold-eyed country wisdom. The people who voted for them, supported them, and followed them would have to learn it the hard way. They commenced their lessons in 1861.

Roy has left a lot out in his narrative, the war may have physically started at Fort Sumter but the true beginning was when South Carolina seceded from the Union, followed in rapid succession by six other states. (The other four seceded after Lincoln called for troops “to put down the rebellion.” In short, the Civil War was the result of politics and political miscalculation on the part of Lincoln and his rabid supporters.

There was plenty of miscalculations and rabid support throughout the country.

When state militias start taking over Federal installations or arsenals, I am not sure what was expected by the seceding states in which how Lincoln could respond? This was not a political miscalculation, it was a show of force to stop others from doing so before there was nothing left to defend. Lincoln rarely acted on impulse, and his call for troops was long after the seceding states were organizing and training their own militias.

There is nothing in the constitution that says a state can,t leave the union.

Exactly so. In fact the text used to instruct cadets at West Point stated this . I think the text book was written by a man named Rauls but I am going from memory. The continuing occupation of Ft. Sumpter blocked the shipment of agricultural goods out of South Carolina which was her economic lifeblood.

Name a country where the minority gave up power peacefully. Ireland, Haiti, Algeria, Rhodesia, India, South Africa, etc…