by Kurt R. Nelson

Most Indian battles were small affairs, often company-sized engagements. Many were fought between equally numbered forces, or if disproportional, the U.S. Army often fought against a larger force using superior fire power and coordinated tactics to overcome the disadvantage of its smaller number. But one war was notable not only for the extreme size difference in the two opposing combatants, but also for the fact that the less numerous antagonist repeatedly beat the larger army. In the case of the Modoc Indian War, the U.S. Army would eventually field a force nearly 20 times that of the Indians and still lose nearly every battle.

[text_ad]

The seeds for the conflict arose out of the Treaty of 1864. During the Civil War, the Indian wars of the Oregon Country were fought largely by the First Oregon Cavalry. In southern Oregon and northern California, the major war tribes were the Klamath and the Paiute. These last would continue to contribute to Indian resistance up to the Bannock Indian War of 1878. By contrast, the Klamath, having fought the whites for 15 years, accepted a reservation and a fort (Fort Klamath, established in 1862 by the First Oregon) with the Treaty of 1864. Included in the treaty was the small tribe named the Modoc.

The Troublesome Modoc

The Modoc had originally been troublesome to whites crossing the Applegate Trail, but then had learned to live with the white settlers, particularly the miners of Yreka. All the Modoc desired was to have a reservation of their own based on the Lost River of Oregon and Tule Lake in California. Instead, they signed a treaty, which they did not understand, giving up their claims in return for a portion of the Klamath Indian Reservation. In 1864, the Modoc moved onto the reservation. It contained two of their traditional enemies: the Klamath and the Paiute; further, it did not include their home of the Lost River. In 1865, the treaty not having been ratified by the U.S. Senate (and was not until 1869), the Modoc left the reservation and returned to the banks of the Lost River. There they lived in relative calm despite the growing encroachment of the whites.

After the treaty was ratified by the Senate in 1869, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Alfred Meacham, went to the Modoc to persuade them to return to the official reservation. Meacham was sympathetic to the Modoc desire for a reservation of their own, and promised to aid their cause, if only they returned. Meacham made his case to one of the most influential chiefs of the Modoc, Kientpoos. Because of the difficulty in pronunciation, many of the Modoc had gained a “white” name from the interaction with the settlers and miners of the region. Kientpoos had been given the name history has recorded: Captain Jack.

Desiring to live in peace, Captain Jack led his and other tribes back to the Klamath Reservation. In the intervening years, the reservation had not grown more accommodating for the Modoc, and after a few months of difficult interaction with the other Indians, the Modoc left the reservation again. Superintendent Alfred Meacham tried to keep the Modoc on the reservation, but his promises of attempting to gain the Modoc their own reservation if only they stayed were lost on the Modoc leaders. When promises of their own reservation failed, Meacham threatened the Modoc with being forced back to the reservation by the Army. The Modoc hated the Klamath Reservation and longed for their Lost River. Despite Meacham’s pleadings, the Modoc moved south to live along the white man’s boundary of the Oregon-California state line.

In the next few years a change in leadership in the local Indian Affairs office cost the Modoc their friendly ear. The new superintendent, Thomas B. Ordeneal, was less tolerant than Alfred Meach- am had been. In July 1872, the Indian Bureau endorsed Ordeneal’s plan to have the Army move the Modoc back onto the reservation. The Bureau forwarded authorization to the Army’s Department of the Columbia commander, Brig. Gen. Edward R.S. Canby.

General Canby issued orders to the District of the Lakes commander (that being the district that included the Klamath Reservation), Lt. Col. Frank Wheaton, 21st U.S. Infantry. Colonel Wheaton was based at Camp Warner, in south-central Oregon. The only advice General Canby gave the colonel was to use sufficient force to prevent the Indians from being tempted to resist. Because the escort of Indians was more easily accomplished by cavalry, Colonel Wheaton delegated the mission to Major John Green, who commanded the cavalry post at Fort Klamath. Not only were cavalry better suited for the mission, but the fort was closest to the reservation and the Modoc on the Lost River.

In spite of the authorization granted in the summer, Ordeneal did not ask for Army support until the late fall of 1872. Then he sent a message to Major Green asking him to send troops “at once.” The message implied an urgent need, and without consulting his superior, Colonel Wheaton, Major Green dispatched troops. However, General Canby’s admonition to use sufficient force had not descended through the chain of command from Canby through Wheaton to Green to the troop’s commander. Instead, B Troop, First U.S. Cavalry, was sent. Captain James Jackson was ordered to bring back the notable warlike Modoc with only three officers and 40 enlisted men.

Return with B Troop Or Else

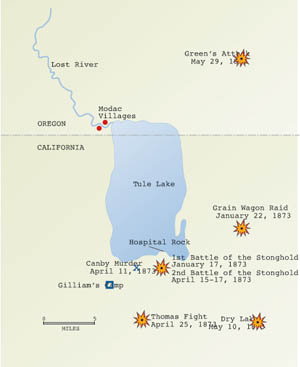

B Troop found the Modoc where they expected, on the Lost River just north of the Oregon-California state line. On the west bank of the river was Captain Jack’s village, with about 80 individuals, of whom maybe 30 were warriors. A short distance away on the east bank was Hooker Jim’s village, another band of Modoc. Captain Jackson believed if Captain Jack’s band was removed, the others would not be a problem. Therefore, on the morning of November 29, 1872, B Troop moved at dawn to the edge of the village. There Captain Jackson gave his ultimatum: Return with B Troop to the reservation or else. Nearby ranchers gathered a safe distance away to watch the events unfold.

Instead of heeding the cavalry’s orders, the Modoc quickly armed themselves and assumed a defensive position. Seeing the action on the Modocs’ part, Lieutenant Frazier A. Boutelle believed the Indians were preparing to attack and opened fire. Quickly a general firefight developed. Giving cover fire so the women and children could flee, Captain Jack held his ground for about a half an hour and then moved south to Tule Lake. His tribe then escaped by boats to the south shore. The Modoc suffered one killed and one wounded. Captain Jackson’s command suffered one killed and seven wounded, one mortally.

But this was only half the battle of Lost River. The ranchers, seeing the cavalry attack Captain Jack, joined in and advanced on Hooker Jim’s camp. They were easily repulsed, with two killed and one wounded, being forced to take refuge in a rancher’s cabin. Hooker Jim’s band moved to the south by way of the east shore of the lake. As they made good their escape, they killed 14 unsuspecting settlers.

The two Modoc bands united in the harsh lava beds south of Tule Lake. Determined to resist the white aggression, they moved into the natural redoubt. They quickly brought supplies, including cattle, into the superb defensive works. Water was easily obtained at the lake.

Once word reached Fort Klamath of the defeat, Major Green mustered the rest of his command and sent word to Colonel Wheaton. At Camp Warner, the colonel ordered more troops into the field, and called for reinforcements from Forts Harney, Bidwell, and Vancouver. Further, two companies of Oregon Volunteers (Companies A and B, Colonel John Ross commanding) and one of California militia moved to support the regulars.

Underestimating the Modoc

One example of Colonel Wheaton’s expanded command was G Troop, First U.S. Cavalry, posted at nearby Fort Bidwell, Calif. Captain Reuben F. Bernard moved quickly once word was received. He ordered his company’s first sergeant, “Black Jack” Raymond, to order “Boots and Saddles” with four days’ rations. Word quickly spread that the troop was heading to fight the Modoc. G Troop headed for Tule Lake.

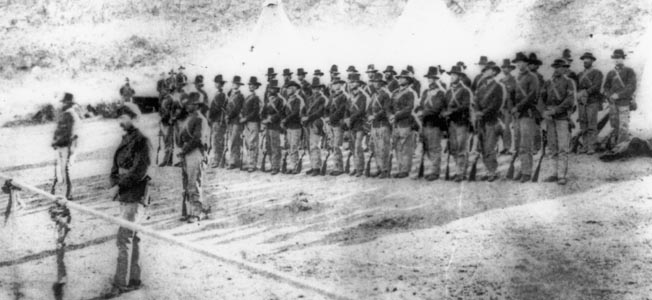

There, Captain Bernard reported to Colonel Wheaton, who had assumed field command on December 21, 1872. It was a cold Christmas as the troops of the First Cavalry, 21st Infantry, Oregon Volunteers, and California Militia gathered. Wheaton soon had about 225 men of the Regular Army plus another hundred volunteers ready to fight the combined strength of Captain Jack and Hooker Jim’s bands, which totaled about 60 warriors. Although Wheaton believed the Modoc had about 150 warriors (Wheaton’s scouts misinterpreted the signs and took the total number of Modoc as being all warriors), he was confident that with about a two-to-one advantage (which was really four-to-one) he would quickly overrun them.

However, the Modoc did not plan to wait to be overrun. On December 21, the same day as Colonel Wheaton’s arrival, the Modoc made a foray. Their scouts had reported a supply wagon train headed toward them, but lightly guarded by five troopers forming a corporal’s guard. Slipping out of their redoubt undetected, the Modoc attacked the wagons and the five cavalry troopers providing an escort. In the surprise attack, two troopers were quickly wounded. However, the corporal and the two other privates gave cover fire, holding off the Modoc until Captain Bernard arrived with more men, driving the Modoc off. Despite being within a half-mile of G Troop’s camp, Privates Sydney Smith and William Donahue died of their wounds. While Wheaton dismissed the attack, believing it was a sign of a Modoc attempt to evade his trap, he still gathered his forces to overrun the Indians.

Wheaton planned to surround the Modoc in their lava beds and take them in a pincer movement. From the west he had Major Green assume command of one attack force. His own contingent would be the main striking force. He would command Companies B, C, and F of the 21st Infantry, while attacking mainly with Troops F and H of the First Cavalry. In addition, he was to be supported by several howitzers under the direction of Lieutenant W. Miller, also of the First Cavalry.

The north end of the lava beds was bounded by Tule Lake. To guard the southern end, Colonel Wheaton ordered the two companies of Oregon Volunteers, as well as the California Militia (really no more than 24 independent riflemen not under company structure), to stretch across the southern lava beds as a blocking force.

Wheaton’s second half of the pincer would advance from the east. Commanding the squadron was Captain Bernard. He had his own troop, G (under the command of his First Lt., J. Kyle), and Troop B, Captain Jackson’s troop, still in the field. The attack was set for January 17, 1873.

The Modoc Surged Towards the Retreating Troops

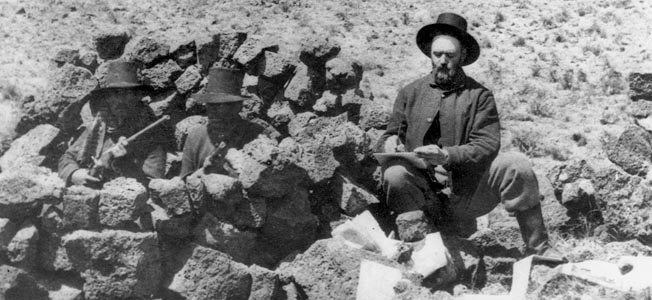

There had been no reconnaissance, however, and Wheaton had no idea what he would find as his line of skirmishers advanced. But Captain Bernard, an experienced soldier since the1850’s First U.S. Dragoon’s fights against Cochise, was unprepared to advance blindly. Thus on the morning of the 16th, Bernard moved his troopers into position early and advanced his men. The fog was so dense that even by noon the visibility was only 50 yards. Deployed at 25-yard intervals, Bernard’s men advanced slowly. As they did, the fog lifted sufficiently for them to see the Modoc. Not wishing to blunder into the camp unsupported, Bernard ordered his men to retreat, having made his reconnaissance in force.

But the Modoc were not about to let Bernard leave uncontested. They opened fire. To provide cover, Bernard ordered his retreat by companies, each company in turn moving back 50 yards and then turning to give cover fire to the next company. First B Troop moved back and then were leap-frogged by G Troop. But the Modoc surged forward and leftward to outflank the retreating cavalry troopers. Fearing his men would soon be successfully flanked, Bernard personally led a charge, driving the Modoc back into their redoubt. The two troops then retreated with only ineffective, long-distance rifle fire. Once the two troops had retreated, they were able to care for their three wounded men at a position soon to be known as Hospital Rock.

Bernard now knew his men would have to advance across very rugged ground, torn by deep chasms, under the direct fire of the Modoc. Still, Bernard moved forward with his two troops, ready to attack at dawn on January 17 in support of the main effort, which was to come from the west under Major Green.

At dawn, the sun’s light was defused in a dense fog, even thicker than the day before, throughout the lava fields. Bernard had his two troops return to the position from which they had drawn Modoc fire the day before. Now all they needed to do was wait until the designated time for the attack to begin.

As his watch marked the moment, Bernard ordered his men to attack by shouting, “Charge!” The Modoc immediately opened fire in an even more intense display than the day before. Immediately Lieutenant Kyle was hit while leading G Troop. Captain Jackson sent Lieutenant Boutelle over to assume command. But advance was impossible across the lava-strewn field against a well-fortified enemy giving good effect with rifle fire. Bernard ordered his advance halted. He now had one killed and five more wounded to be sent to Hospital Rock.

From the west, Major Green started forward with his larger force. He began his attack with F Troop, Captain David Perry commanding, making a cavalry charge to sweep around to the southwest of the Modoc. But the ground was ill-suited for cavalry, and at a deep ravine Perry’s command had to stop and dismount, and they soon found themselves trapped, neither able to advance nor retreat. Green then ordered his infantry forward, which rescued the trapped cavalry, and prepared for the next advance. Instead of moving his strong force forward to connect with Bernard’s (which had been ordered to move toward the south for an attack from the southeast), Green was little advanced and still a long way from penetrating the Modoc lines. Instead of a frontal attack, Green ordered his infantry to move to the left, toward Tule Lake, to find an easier way into the Modoc lines. All the while Green had his howitzers firing.

Howitzer Hindered by Fog

Bernard’s forces were making a flanking movement, too. With his two companies now formed at five-yard intervals in the thick fog, Bernard advanced to his left. He made good progress for about 300 yards in preparation for an attack from the southeast, but then ran into the same deep ravine that had halted Perry’s advance. The ravine cut nearly three-fourths of the way around the Modoc, creating a very effective dry moat over which the troopers could not advance, but over which the Indians could fire.

Worse, in the fog, much of the howitzer fire was conducted blindly, frequently going completely over the Indian camp. The result was that a great deal of Bernard’s advance was made into an artillery barrage. Between the artillery fire and the deep ravine, Bernard was unable to advance farther. Consequently, he retreated to his original jump-off point.

Within an hour of sunset, the fog finally lifted. One result was that Major Green could communicate with Captain Bernard. When Bernard told Green about the howitzer fire, Green put an end to it. This allowed Bernard to probe toward the Modoc again. Major Green decided to support the action by making a major push of infantry to the north to connect with Bernard in that direction. At first hesitant, the infantry moved forward once given encouragement by Major Green. He led by example. Much respected by his troops, “Uncle Johnny” Green jumped up on a rock and exposed himself to Modoc rifle fire. He yelled at his men that they had nothing to fear because the Modoc could not hit him standing out in the open. Green then personally led the charge, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor. But the Modoc quickly responded by redirecting more of their fire against the advancing 21st Infantry companies. Despite some of the companies breaking through to Bernard, most were hit so hard that the infantrymen simply went to ground and cover until darkness allowed them to retreat.

Thus Wheaton’s attack at the First Battle of the Stronghold had been a disaster. No Indians could be reported killed because none had even been seen, so effective was the cover of their defensive positions. But the U.S. Army had suffered 16 killed (all enlisted men) and 53 wounded (nine of whom were officers). Most of the casualties were suffered by the 21st Infantry. Not surprisingly, all of the troops felt dispirited. The California riflemen went home and Colonel Ross led his two companies of Oregon Volunteers home (the Volunteers had suffered two killed and nine wounded, two of whom would die). The troops of the Regular Army who were forced to stay faced a bleak prospect: Not only were the Modoc still in place, now snow had covered the white men’s exposed winter camps, adding to their misery.

A Commission for Peace

When news of the failed attack reached Washington, DC, it coincided with the beginning of President U.S. Grant’s second term of office. Grant had campaigned on a platform of peace with the Indians. Present in Washington (as an elector from Oregon for the Electoral College) was Alfred Meacham. Still considering himself an advocate for the Modoc, Meacham went to Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano with the idea that a peace council could achieve with the Modoc what Colonel Wheaton had failed with his troopers. A peace commission was appointed with Meacham at its head. They headed for Tule Lake.

The Army, however, had not been idle during the interim. Wheaton was relieved of field command and replaced with Colonel Alvin C. Gillem, the First Cavalry’s colonel. General Canby also arrived to determine what had gone wrong. While there, he received word that a peace commission had been ordered. He wired his superiors that a peace commission had little chance of success so immediately after a stunning Indian victory. The reply to Canby was to keep the troops on the defense and to give peace negotiations a chance. In keeping with his orders, Canby had Colonel Gillem re-deploy his forces. Gillem’s camp was pulled back about two miles to the base of a steep hill at the extreme southwestern edge of Tule Lake. On the east, Captain Bernard’s forces were ordered back about nine miles to the Applegate Ranch. On January 20, Bernard’s forces reached the ranch, which at least provided greater comfort to the wounded.

On January 22, the Modoc made another raid against two wagons carrying grain to the Applegate Ranch. The escort fled, and as the Indians plundered the wagons, Captain Bernard arrived with a portion of G Troop, killing one Modoc, wounding an undetermined number of others (who were carried off with the raiding party) and chasing the Indians back into the lava beds.

While the peace commission gathered, so did more soldiers. K Troop, First Cavalry, arrived, as did Company I of the 21st Infantry. In addition, two other regiments took the field, at least in part. The Fourth U.S. Artillery arrived with Batteries A, E, K, and M. Thus, no longer would the howitzers be manned by either cavalry troopers or infantrymen. In addition to howitzers, a unit of Coehorn mortars were brought to the field. The balance of the Fourth Artillery acted as infantry support. In addition, further reinforcement was sent in the form of two companies (E and G) of the 12th Infantry.

Despite the huge increase in manpower, the Army gave the peace commission every opportunity to succeed. After a month of nothing but words, Interior Secretary Delano took the unusual step of putting General Canby in charge of the peace efforts, too. March 24th marked Canby’s first efforts at negotiation.

Tense Negotiations

Canby believed the Modoc would not negotiate while still victorious at arms but rather would have to feel the pressure of the Army. Accordingly, General Canby ordered Colonel Gillem to tighten the ring on the Modoc. Thus on the east, he ordered Major Edwin C. Mason, 21st Infantry, to re-occupy Hospital Rock and to send patrols to the very edge of the lava redoubt. The subsequent pressure helped to clarify both sides’ demands. The Modoc asked for their own reservation located on the Lost River, and General Canby countered with unconditional surrender. The peace talks dragged on.

Fearing that continued war with the Modoc might embolden other Indian tribes, General Canby ordered more cavalry (Troop E) under Major George Sanford, from Fort Lapwai, Idaho Territory, to move to Fort Harney, Oregon. Canby also warned General William Sherman that his forbearance might be seen as weakness and that other Indians might join the Modoc. As his telegram to Sherman noted, “To guard against this, I have ordered Sanford’s troops from Fort Lapwai to Camp Harney, about which post a large number of Pi-Utes are now gathering.” Whether inclined to join the Modoc or not, the Pi-Ute made no further effort to go over to the attack, and so Canby’s move prevented an expansion of the war.

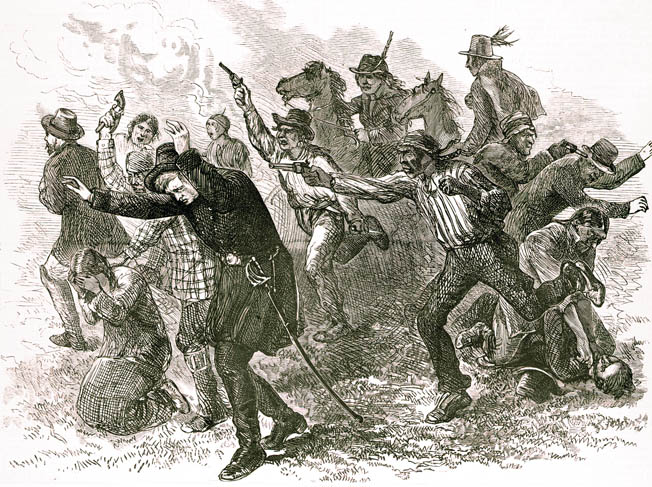

Otherwise, Canby was not so successful. Indeed, the Modoc took the general’s forbearance as weakness and planned accordingly. Canby’s interpreter’s wife was a Modoc and she reported to the general that she had heard of a Modoc plan to kill the peace commissioners. General Canby could not believe the Modoc were capable of such treachery, but in fact they were. While internal debate raged as to the proper course of action, some of the more aggressive Modoc shamed Captain Jack into agreeing to a plan for making two coordinated attacks against the Army’s commanders. On the east, several Modoc would approach Hospital Rock and seek to talk to the eastern commander. Gaining admission, they would shoot him. To the west, in the middle of the peace talks, the Modoc would rise and kill the white’s peace commissioners.

The Indians made their plans accordingly, and picked their day of action, not knowing the date’s significance. It was Friday, April 11, Good Friday, fueling the white men’s outrage when they looked back on it. On the eastern perimeter, the Modoc, carrying a white flag, approached the sentry at Hospital Rock, Private Charles Hardin, G Troop, First Cavalry. They asked to speak with the new commander on the east, Major Edwin C. Mason, of the 21st Infantry. The sentry would not let them pass. Instead, the Officer of the Guard, Lieutenant William Sherwood, walked out to speak with the Modoc. They wished to speak with someone of higher rank and promised to return. Lieutenant Sherwood said he would notify Major Mason and Captains Bernard and Jackson, the senior officers present. None of these officers elected to enter into any separate talks with the Modoc, however, and told Lieutenant Sherwood to so inform the Modoc.

When the Modoc returned, Sherwood and Lieutenant W. Boyle walked out unarmed to tell the Modoc that the other officers would not speak with them. The Modoc turned, walked a short distance, picked up the rifles they had hidden, and, spinning, opened fire on the two lieutenants. Sherwood would soon be dead from his wounds. Boyle was wounded but survived. The Indians escaped.

Coordinated Treachery

At almost the same instance, in the peace council’s tent, the four peace commissioners were meeting with other Modoc. Along with General Canby and Alfred Meacham were L.S. Dyar and the Reverend Eleasar Thomas. In addition there were two interpreters. As General Canby led the council, Captain Jack pulled out a hidden pistol and shot General Canby in the face. Other Indians attacked the other commissioners. The interpreters and Dyar fled, but the good reverend and Meacham fell next to the dying Canby. Despite being shot and stabbed, Meacham survived and fully recovered.

Not only did the coordinated treachery under a white flag enrage the white press, but the loss of well-respected General Canby infuriated the troops. Typical of the reactions was that of Captain Bernard, who had been appointed an officer (from First Sergeant) during the Civil War at Canby’s personal direction. He thirsted for revenge and an attack that would crush the Modoc.

Colonel Gillem lost no time. He did not wait for Canby’s replacement, Colonel Jefferson C. Davis (then of the 21st Infantry and a brevet major general), to arrive. Instead Gillem ordered an attack. His plan replicated Wheaton’s, but with a greater number of troops and more fire power. Beginning on April 15, Gillem ordered an advance. There would be no charges this time. Instead, the soldiers would slowly advance, with fire support, from cover to cover. Again the main thrust was to be from the west, with Major Green commanding. Accordingly, Green advanced, under the supporting fire of the mortars, with three troops of First Cavalry, two batteries of 4th Artillery (acting as infantry), and two companies of 12th Infantry.

On the same day Major Mason attacked with four companies of 21st Infantry, supported by Captain Bernard’s squadron of G and B Troops, First Cavalry. Mason’s attack also had fire support from the howitzers. Despite pressure from two directions, by the end of the day the Modoc were still holding out. Normally the Army would have retreated from their advance positions under nightfall, but not this night. They held their line and brought up supplies. All the while the mortars kept dropping shells into the Modoc redoubt.

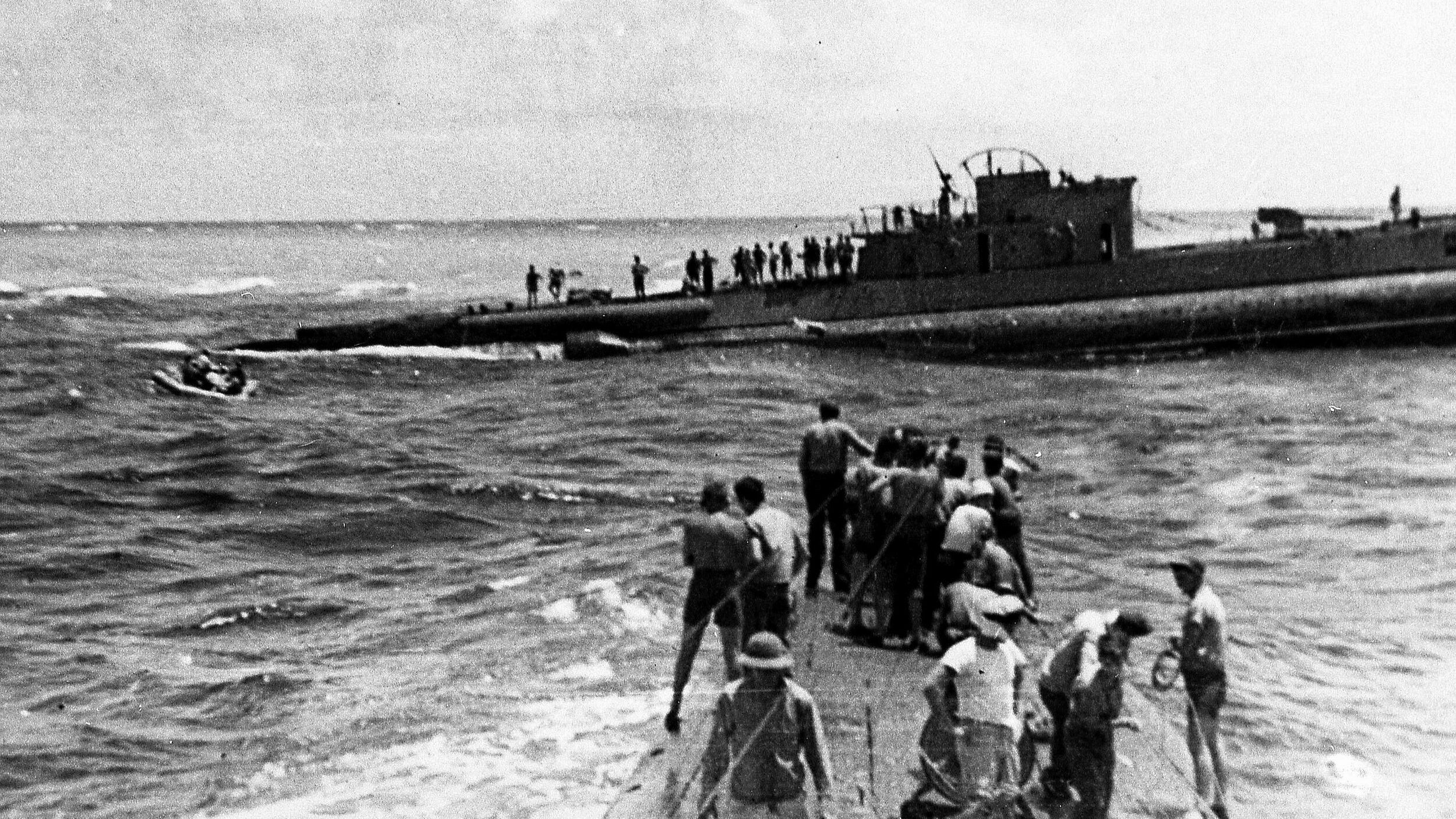

The fight resumed on the next day. Slowly the whites advanced, from cover to cover. Eventually, along the northern sector, the two Army forces joined on the shores of Tule Lake. The juncture deprived the Modoc of their water source. Night fell and again the soldiers dug in and again the mortars lobbed their shells into the Modoc camp. On the morning of the 17th, the whites entered the Modoc camp only to discover the Indians had fled the previous night, leaving only a small rear guard to delay the Army’s advance. The Modoc had escaped through a hole in the Army’s constricting ring, owing to Major Mason’s failure to advance as far as ordered.

The Modocs Retreated to Their Lava-bed Stronghold

The Second Battle of the Stronghold had resulted in far fewer Army casualties and had left the Army in command of the field, but the Modoc had retreated deeper into the wilderness of the lava beds, leaving 11 dead behind (eight of whom were women killed by the artillery).

With the Modoc gone from their stronghold, the Army faced a new problem. When the Indians were inside their lava bed stronghold, the whites at least knew where they were. Having forced them out, now the Army had no idea where they had gone. Colonel Gillem had to find them. He sent out scouts, and he also ordered a reconnaissance in force. Sixty-four soldiers marched out on April 26, under the command of Captain Evan Thomas of the 4th Artillery. He commanded two batteries of artillerymen acting as infantry. Accompanying him was one company of the 12th Infantry,under Lieutenant Thomas Wright.

As the whites marched south, they displayed their limited experience in fighting Indians. Although Captain Thomas ordered out flankers, he failed to correct their alignment—they tended to sidle back in so as to be almost walking next to the main column. When the column halted for lunch, few sentries were set, and they were not very attentive. The lapse allowed the Modoc to crawl close to the resting soldiers, and then spring a surprise attack. Half the command panicked and fled toward Colonel Gillem’s camp four miles north. Thomas organized his remaining soldiers into a defensive perimeter, and then ordered Lieutenant Wright to take some men and charge the ring of Modoc. His plan was to have Wright force an opening toward the northwest that would allow the command to retreat toward Gillem’s camp.

One wrote: “At the first fire, the troops were so demoralized that officers could do nothing with them. Captain Wright was ordered with his company to take possession of a bluff, which would effectively secure their retreat, but Captain Wright was severely wounded on the way to the heights, and his company, with one or two exceptions, deserted him and fled like a pack of sheep; then the slaughter began.”

With Wright killed, the rest of the 12th Infantry retreated back to Thomas’s defensive line. Then Modoc warriors wiped out the remaining command, resulting in 25 killed (including all of the officers) and 16 men wounded.

When Canby’s replacement, Colonel Davis, arrived at his new command on May 2, he found that this latest disaster had caused morale to plummet. He informed General Schofield in San Francisco that “a great many of the enlisted men here are utterly unfit for Indian fighting of this kind.” What was needed, believed Davis, was the dash of cavalry. Shortly after taking command, he ordered his cavalry to act as beaters to drive the Modoc out.

Accordingly, on May 9, he sent out Captain Henry Hasbrouck, 4th Artillery, with one battery of artillery, mounted to act as cavalry, and parts of Bernard’s and Jackson’s First Cavalry troops. Working south, Hasbrouck camped on Dry Lake, a major water resupply point for the Modoc. Early the next morning, the Indians attempted another surprise attack. Initially, the ambush worked as it had with Captain Thomas’s command.

One witness recorded: “I saw a line of Modocs pop up their heads and fire a volley. This caused some confusion. Men rolled over behind saddles and bundles of blankets—no covering however small being ignored, fastening on belts and pulling on boots under a hail of bullets. There was a possibility of a panic, but this was happily averted by Sergeant Thomas Kelly of our troop [Captain Bernard’s own G Troop], who sprang up and shouted, “God damn it, let’s charge!”

The End of the ‘War of Unequals’

Indeed, the cavalry charged into the Indians, driving them away from the desperately needed water. Further, the counterattack overran the Modoc camp and captured much of their dwindling supplies. The Modoc made for new lava beds. Driving the Modoc back into the lava without water had cost Hasbrouck five killed and 12 wounded. But it had allowed Colonel Davis to close on the latest Modoc lava redoubt where, on May 14, he charged into their last big defensive position. The attack caused the Modoc to split up in an attempt to evade the Army.

Hasbrouck’s command caught up with one band, Hooker Jim’s, near Butte Creek on May 18, and quickly overran it. Four days later Hooker Jim led his people into Colonel Davis’s camp and surrendered. Major Green led another column of First Cavalry after a fleeing band and attacked Captain Jack’s camp on May 29 in Langell’s Valley, Ore. On June 3, a weary Captain Jack led his family, all that was left of his band, into Captain David Perry’s waiting F Troop command and surrendered. The war was over.

The epilogue to the war began on July 1, at Fort Klamath. In an eight-day court-martial, Captain Jack and six other Modoc leaders were tried and found guilty of murder. They were sentenced to death. President Grant commuted two of the sentences, but on October 3, 1873, four Modoc, again led by Captain Jack, were escorted to the gallows built at Fort Klamath and were hanged.

All Indian tribes had one area they considered sacred. Never had any tribe held dear so prophetically a named homeland as the Modoc Lost River. The Modoc lost their war, and they lost Lost River. What was left of the tribe was shipped off to Oklahoma. The war of unequals was over.

There was no water there. Today it is known as Dry Lake and only holds water in the early spring. I did find a .45-70 slug at the site which I put back. The Salient point about this battle is that the Army captured their ponies laden with fixed ammunition and powder. With no ammo or powder and the break with the Hot Springs tribe over the death of Ellen’s Man George, the rest was a foregone conclusion.