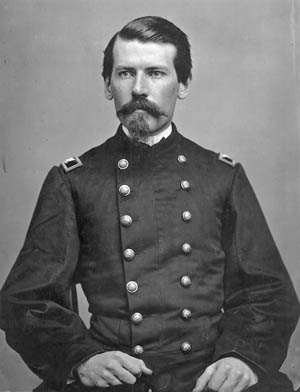

By Richard H. Owens, Ph.D.

Horace Porter was born April 15, 1837 in Huntingdon, Pa. He traced his ancestry and family motto, “Vigilantia et virtute,” to William De La Grange, who accompanied William the Conqueror to England in 1066. His grandfather, Andrew Porter, served as an artillery officer under George Washington. His father, David Rittenhouse Porter, studied law but turned to agriculture and industry, managing a farm and an ironworks. Active in Democratic politics, D.R. Porter served two terms as Pennsylvania’s governor from 1839 to 1845. Like many Pennsylvania Democrats, he opposed slavery and was pro-Union.

Young Horace obtained appointment to West Point and entered in the summer of 1855 in one of only two classes in the academy’s history with a five-year term. Eighty-one men entered with Porter. Forty-one graduated five years later on July 1, 1860. Porter graduated third in his class. He demonstrated discipline, confidence, teamwork, and leadership, and earned regular citations for quality and good example. In his fifth year, he became adjutant of the corps of cadets, second only to cadet regimental commander.

Young Horace obtained appointment to West Point and entered in the summer of 1855 in one of only two classes in the academy’s history with a five-year term. Eighty-one men entered with Porter. Forty-one graduated five years later on July 1, 1860. Porter graduated third in his class. He demonstrated discipline, confidence, teamwork, and leadership, and earned regular citations for quality and good example. In his fifth year, he became adjutant of the corps of cadets, second only to cadet regimental commander.

In January 1860, Second Lieutenant Horace Porter was asked to remain at West Point after graduation to serve as an artillery instructor. The army recognized his qualities of leadership, communication, and administration in an era when most junior officers were assigned tasks escorting wagon trains and manning forts in the West. Porter welcomed the assignment and recognition of his abilities; he was enthusiastic about his prospects.

Unknowingly Preparing for War

By March 1860, Porter and his classmates were, he wrote, “making necessary preparations for one of the greatest events in our lives,” not knowing that in a year they would be at war. Of course, there had been signs at West Point of growing sectional division in America over slavery; the 1856 presidential campaign was especially bitter and caused divisions among cadets. Porter disapproved of slavery on grounds that it was inhumane, contrary to American traditions of liberty, and an irrational political and economic system.

After a semester of instructional duty at West Point, Porter was assigned in the winter of 1860-1861 to the army arsenal at Watervliet, NY, supervising production and shipment of munitions and guns. The assignment pleased Porter for its location near Albany, home of his fiancée, Sophie McHarg, whom he had met at West Point in 1859. At first, the challenges at Watervliet interested and occupied Porter. He wrote to his father that General Winfield Scott seemed determined to have sufficient troops and ammunition in Washington to quell possible trouble at Lincoln’s inauguration. Porter noted that “tons of ammunition had been dispatched to the capital.” More significantly, he hoped “these preparations may not be necessary and the states may yet come to some amicable settlement.”

The principal issue for Porter was the Union. “The state of affairs is truly alarming,” he wrote his father in what would become a stream of letters during his war years to him, his mother, and his fiancée, “and I fear we may soon see the worst. In my mind, nothing can justify the acts of states that in the most precipitate manner pass an act of secession, seize government property, and fire on government vessels, before the Republican administration ever went into power.” Porter expressed some sympathy for classmates who left the army to fight for their states. But he added that there was a greater sense of loyalty to country than to states among the officers.

In April 1861, Porter and his colleagues at Watervliet worked feverishly to meet demands for munitions. On April 11, Porter noted “enormous orders for supplies came from General Scott.” In 36 hours, Porter and his men filled orders that normally took two weeks. Proud of his accomplishments at the arsenal, he appeared uncertain whether he would see action because “as long as there are so few of us here, I cannot get away from the Arsenal.” Porter was released briefly from his duties that spring for a secret assignment carrying to Washington dispatches related to production, inventory, and transportation at the arsenal. He wore “citizen’s clothes for disguise.” The information was too important to be sent via telegraph or post. Porter’s first experience as a courier excited him.

“I am Moving Heaven and Earth to Get with General McClellan”

In recognition of his work at the arsenal, he was promoted to first lieutenant of ordnance on June 7, 1861. In September 1861, he was given active interim command of the arsenal while its commandant was on leave. But his anxiety over a field appointment grew, undoubtedly whetted by his clandestine mission to Washington. “I am moving heaven and earth to get with General McClellan before he starts south,” he wrote. Porter was determined “not to stay here while the war continues.” Nevertheless, he spent most of October 1861 waiting, as did McClellan’s Army most of the time.

Finally, late in that month, Porter received orders. He saw his first action in November at Port Royal, SC, near Savannah, Ga. His initial battle observations were typically naive and optimistic. Describing the barrage against Confederate forts at Hilton Head, he wrote of “a beautiful sight as we watched it through our glasses.” Later battles convinced him that war was hardly glorious. At Port Royal, he also discovered that maneuvering artillery in wet coastal areas produced much discomfort. “I had been working all night with my boots full of water and was pretty well worn out,” he confided. Later, Porter “found an old candle, went up to an empty room, lay down on the floor in my wet clothes, and got a few hours sleep.”

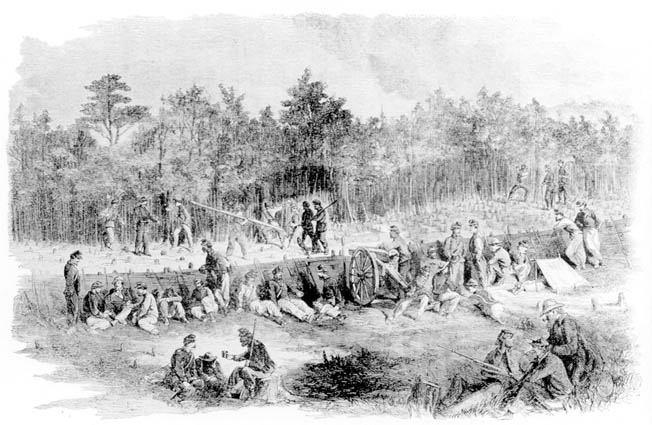

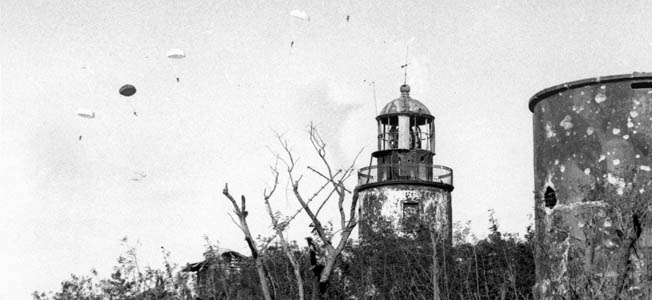

His superiors duly noted Porter’s efforts. In December 1861, he was named chief of ordnance for the assault against Fort Pulaski. He discerned that Fort Pulaski, and eventually Savannah, could be taken through patience and intelligence, not bloody assault. “We can get to Savannah the back way and save lives and time; the Fort will then fall of itself. It has but two months’ provisions,” he wrote. But Porter was not making the decisions. His superiors decided to reduce Fort Pulaski, not attempt the end run that Porter advocated. They did follow his advice, however, on battery dispositions and other ordnance operations for which he had been trained and demonstrated considerable talent. He displayed ingenuity by persuading Connecticut volunteers to improvise whittled wood fuse plugs for one battery. Other problems he faced were slaves who flocked to Union lines and the unpredictable quality and attitude of volunteer troops.

Porter’s estimate of two months of supplies in Fort Pulaski belied Confederate ability to forage, improvise, and husband resources. By February 1862, the fort remained intact. Union morale was plagued by rumors that they might withdraw from Savannah after weeks of futile effort and little progress. Soon, however, firmer decisions and more strenuous efforts were made. In March 1862, serious siege preparations commenced. Porter was in the forefront of activity, giving advice, supervising gun placements and dispositions, selecting targets, and commanding 11 batteries totaling 36 guns.

On April 11, after an intense two-day bombardment, Porter reported that Fort Pulaski was in Union hands. Still naive but exuberant, he saw it as “Sumter revenged.” He proudly noted that as commander of the artillery batteries, “I fired the first gun.” Porter came under shelling during the battle and feared “several times I was a goner.” Describing a captured Confederate officer named Freeman after the fort’s surrender, Porter noted he “was a Union man and heartily wished the war was over, but that the blood of the South had been spilled and he would fight to the end.” Porter closed optimistically that “the Fort is all knocked to pieces, our guns worked beautifully, and our firing was much better than the Rebels’.”

Porter’s Stark Realizations About the War

Several things became clear to Porter during the Fort Pulaski campaign. The war could last a long time. The Confederates were formidable adversaries despite superior Federal firepower and ordnance. Senior Union officers, whether Regular Army or volunteers, often were politically motivated, misinformed, or simply inept. Porter recognized his own talents as a leader, soldier, and engineer. Finally, as the Confederate officer Freeman had convinced him, emotion and arguments for slavery, secession, and war were major factors for the South.

Despite increasing responsibilities and reputation, the Fort Pulaski victory was diminished for Porter by knowledge that “they’re giving up on Savannah.” To sweeten the disappointment, however, Porter received an engraved sword and was breveted captain “for gallant and meritorious services” on April 11, 1862, the date Fort Pulaski fell. He announced the promotion and described his role and responsibilities by noting: “I am sort of acting brigadier general.” But the Union campaign in the Carolinas had stalled. Porter chaffed at slow progress in a secondary theater of operations. He worked to prepare heavy artillery for the James Island, SC, expedition, and on June 16, 1862, took part in the assault against Secessionville, SC, where he was wounded in the hand by a shell fragment.

Finally, in July 1862, Porter was named to General George McClellan’s staff as chief of ordnance of the Armies of Virginia (as it was then called). The assignment reflected lack of battle experience among Union officers at that early stage of the war as well as the reputation Porter earned at Fort Pulaski. Porter was justifiably proud of his record and the assignment, although he exaggerated when he wrote: “You see this is the greatest position a young man has ever held in this country.” Porter soon grew disappointed at the new assignment, however, and became increasingly critical of incompetence, political motives, and myopia among Regular Army officers in the field and War Department.

Joining McClellan’s staff after the Seven Days Battles of June 25-July 1, 1862, Porter spent August reorganizing the ordnance department which, like much of the battered army, was in disarray. Porter noted his growing frustration at the lack of action, movement, and anticipation of Confederate moves. “The oldest and generally most inefficient officers fall in at the top of the list and become chief,” he complained while Robert E. Lee was advancing north to Antietam without resistance. Moreover, Porter learned to respect Lee and other Southern field commanders, a respect that grew with his later experience in the West and in Virginia.

“Do Not Mention This State of Affairs. Let All People Have Perfect Faith in the Army.”

Porter rendered fine service in organizing the artillery transfer from McClellan’s base on the James River in Virginia to Antietam. But he was dejected both by being left behind at the time of the battle and the routine promotion of officers based on seniority rather than ability—another man was placed above him as chief of ordnance. “I am sending 440 wagons of ammunition to the Army at Frederick [Maryland], enough to last it all year if not wasted,” he wrote at the time. “If he [Shunk, who superseded Porter] is up to his old Port Royal tricks, the Army will never get a round of it.” Porter opined: “McClellan is so terribly afraid of hurting anyone’s feelings that he lets affairs go on in this way for fear of offending some old fogy by promoting a younger man over him.” Confusion was rampant and leadership weak, he declared. “At present, Marcy gives one order, McClellan another, Halleck another, and Stanton another. The feeling here is one of deep depression.” Yet, Porter cautioned in this letter to his mother, “Do not mention this state of affairs. Let all people have perfect faith in the Army.”

Porter realized early that McClellan was not the right man to lead the Union to victory. He was critical of McClellan well before negative comments about him became common. “It is a shameful thing,” Porter wrote, “that we are exactly where we were a year ago and worse in some respects.” Fortunately, General Ripley of McClellan’s staff liked Porter and asked him to become chief of ordnance of the Army of the Ohio under Maj. Gen. Wright, with whom Porter had served in the Carolinas. Wright had established headquarters at Cincinnati, needed a good chief of ordnance, and asked for Porter, who was glad to accept.

In October 1862, Porter wrote to his mother that he thought the Union Army too amateurish and intent on “toy-soldiering.” He was particularly upset by news that McClellan had decided against a fall campaign. At first, things moved slowly in the West, too. Then, in late January 1863, Porter was promoted to chief of ordnance of the Army of the Cumberland under General William S. Rosecrans.

Porter received permanent promotion to captain on March 3, 1863. By now, after three years in uniform and two years of war, he had become accustomed to army routine. He realized the war would go on for a long time and had become “a widespread and mammoth war of nations.” As the Army of the Cumberland advanced south, the young man lamented the cost of war, separation from family, and soaring food prices. Around Murfreesboro in April 1863, amid a war of attrition, he reflected: “We have entered upon the second year of the war, and will have many a long campaign before it ends.”

By the end of June 1863, the army had advanced on Tullahoma, Tenn., passed the Elk River on July 3, and crossed the Tennessee River on September 2. Porter understood Rosecrans’ plan to outmaneuver and take Confederate General Braxton Bragg from the rear. But he realized that success in Tennessee would not end the war. By August 25, 1863 Porter believed Bragg was on the run, and he was buoyed by local demonstrations of Union support. But reality of a different sort soon slapped Porter and the whole Army of the Cumberland.

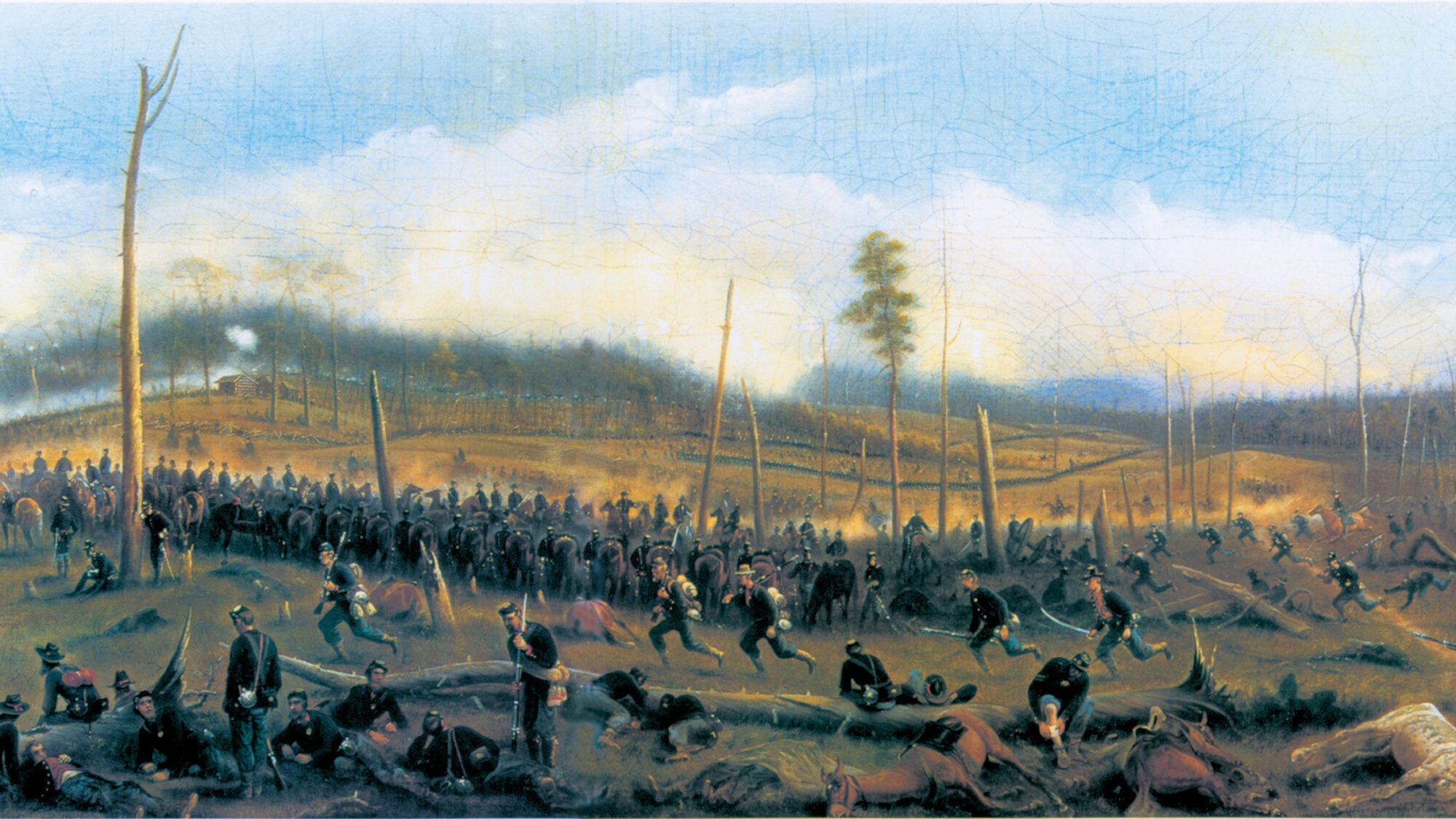

15,000 Men Dead; The Bloodiest Battle of the War

Rosecrans miscalculated. After pushing Bragg’s Confederates into Georgia through the summer of 1863, he assumed Rebel forces were still on the run. Bragg, however, regrouped in September and turned to fight at Chickamauga, 12 miles south of the Union base at Chattanooga. In a letter following the battle, Porter noted its importance. The brevity of the letter betrayed his fatigue and the battle’s physical and emotional impact on the Federals. “We have been fighting the great battle of Chickamauga, as it will probably be called, for the last two days. Yesterday [September 19], we repulsed the enemy at all points against fearful odds, but today [the 20th] have been driven back twelve miles [to Chattanooga].” Porter concluded: “This is the bloodiest battle of the war. We have lost probably 15,000 men.”

A few days later he described the engagement in detail, providing rare but important information on his role. For his actions at Chickamauga on September 20, 1863, confirmed by other witnesses, Porter received the Medal of Honor. As Porter told it, during the Union retreat on the afternoon of September 20, he and another officer, Captain J.P. Drouilliard, whom he had known at West Point, reached the crest of a hill. “I told him [Drouilliard] I was going no farther, as long as we could hold ten men together. He joined me, and by urging and threats we formed nearly a hundred men.”

Stragglers and unattached officers were incorporated into the cohort that eventually weakened under artillery fire and several bayonet attacks. But they at least led the Confederates into believing a much larger unit held the hill. Porter delayed the Southern advance for about 20 minutes until artillery finally cleared the way. By the time Porter ordered the remaining soldiers on the hill to retire, most defenders had been killed or wounded under constant Rebel assault. Meanwhile, other Union troops escaped the Southern attack. Union forces under General George Thomas regrouped to prevent the retreat from becoming a rout. Porter wrote to reassure his sister on two accounts. “I was never in better health or spirits in my life. Do not believe any newspaper rumors about us [being beaten]. We are all right now.”

Chickamauga was an important event for the North and for Porter. It marked the emergence of George Thomas and ended the uncertain and hesitant command of Rosecrans (who in later circumstances did well). Porter and most Union troops survived. They could afford manpower losses; the South could not. Furthermore, Union troops were tempered, and reversal at Chickamauga in Porter’s estimation was “not serious. Nothing could exceed the bravery of our troops. Their endurance and courage saved our army and Chattanooga.” He added that more vigorous and able leadership was needed. He wrote, “There must be some great changes among our general officers before another battle.”

Meeting the Famed General Grant

There were. Chickamauga brought full command in the West to Ulysses S. Grant. It also gave Porter further opportunity to demonstrate valor and leadership under fire and to meet Grant, who became Porter’s most significant role model.

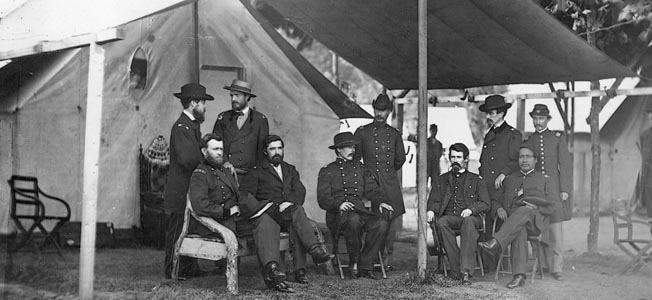

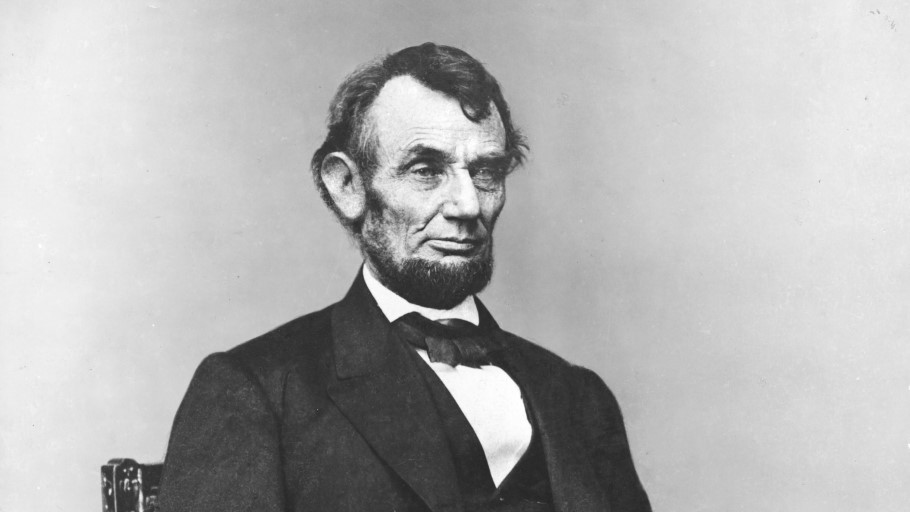

On October 23, 1863 in Chattanooga, Porter met Grant for the first time. The Union general had a major impact and influence on the younger man, who never lost admiration or respect for the plain-spoken soldier who became his commanding officer, mentor, president, and friend. Porter saw in Grant the character and attributes of a man far more complex than the tough public exterior. To Porter, Grant possessed many traits that also endeared Abraham Lincoln to both Porter and America: humanity, patience, determination, humility, simplicity, strength under pressure, and sensitivity. Although he had the opportunity to meet Lincoln more than once, Lincoln was a more distant hero. Porter was with Grant every day for over a year of bitter fighting in Virginia, through several years in politics, and later through Grant’s period of disgrace and illness.

Their first meeting was hardly auspicious. Porter met Grant in a dark room crowded with other officers. General Thomas, then commanding the Army of the Cumberland, introduced Porter to Grant, who had been assigned command of all Union armies in the West. From then on, particularly after he was assigned to Grant’s staff in Virginia, Porter believed that despite humility, informality, small stature, and minimal pomp and staff surrounding him, Grant was the man who would bring Union victory.

Although the Army of the Cumberland survived Chickamauga, Porter realized some problems went beyond the need for more vigorous leadership. “Most of the men were without overcoats, and some without shoes; ten thousand animals had died of starvation, and the gloom and despondency had been increased by the approach of cold weather and the appearance of autumn storms.”

Porter understood logistics. At their meeting on October 23, Grant asked him how much ammunition was on hand following Chickamauga. Porter replied there was only enough for one day of intense battle. The next day, Thomas assigned Porter to accompany Grant’s reconnaissance of their positions around Chattanooga. Grant again asked Porter to review the ordnance situation and shared with Porter some directives he was preparing for William Tecumseh Sherman. Grant quickly became aware of Porter’s experience, knowledge, and abilities with siege warfare and artillery. The young officer impressed Grant, who liked his frank and honest assessments. Porter liked what he saw in Grant, too. He wrote that Grant was direct, open, intelligent, offensive-minded, dedicated, and had “singular mental powers and rare military qualities.”

Mutual Respect Between Soldiers

Porter’s opportunity to serve directly under Grant was, however, still a half a year away. In his immediate future was a possible transfer to the ordnance office in the War Department. The news again provoked Porter’s criticism of “armchair generals with seniority, contacts, rank, and no experience or zeal for the front.” Thomas, with Porter’s approval, wrote to Grant, asking the Western Commander to intercede so that Porter could remain with Thomas. Grant admitted he had little chance at that time of reversing an order from General Henry Halleck. But he gave Porter a letter for Halleck requesting that Porter be reassigned as soon as possible for duty with Grant himself. Grant also requested that Porter be promoted to brigadier general when assigned to his staff. Based on evaluations of Thomas and others, Grant’s letter characterized Porter as “one of the most meritorious and valuable young officers in the service.”

On November 6, 1863 Porter left for the War Department. On December 23, 1863 Horace and Sophie were married in Albany. By January, they were settled in the nation’s capital. But Porter had no desire to remain behind a desk.

In spring 1864 Grant was called east to command all Union armies. On April 4 Porter was assigned as Grant’s aide-de-camp as a lieutenant colonel. As his responsibilities grew, so did Porter’s perspective on the war. He noted that under Lincoln and Grant politicization of the army was at last being subordinated to the war effort. He also gained insight into the political character of the war and its prosecution, observing that finances, morale, elections, and political consensus were important elements in achieving victory. The young officer was proud to be part of Grant’s staff and a force “unequaled in history.”

Although Porter referred to the Confederates as the enemy, there is no evidence in his correspondence or records that he held Confederates in contempt. By 1864 his early critical comments about secessionists and slaveholders had been tempered by feelings of common humanity, suffering, and wartime experiences shared by both armies. A key meeting on May 3, 1864 to coordinate Union strategy reflected the attitude he learned from and shared with Grant. Porter knew what was needed to win the war. He was pleased to be at the center of decision making. Grant’s military analysis included advantages of interior lines, terrain, and supplies. Porter appreciated Grant’s plan at that May 3 meeting “to launch all his armies against the Confederacy at the same time, to give the enemy no rest.”

Porter liked the democratic, informal style of Grant’s headquarters. Grant preferred staff members to dine with him rather than in small messes according to rank. After the politics and formality of McClellan’s staff and the War Department, Porter enjoyed the chance to speak his mind, learn the strategic picture, and participate in decisions. Grant was criticized in military circles outside the Army of the Potomac and by politicians. Porter disapproved the negativism, particularly regarding Grant’s alleged slowness in moving against Lee in the spring of 1864. Porter speculated that Grant’s critics were not aware of his responsibility to direct all Union armies, not just the Army of the Potomac.

“Hell Itself had Usurped the Place of Earth”

Porter saw action throughout the campaign toward Richmond that spring. On May 6, 1864 he was breveted major for “faithful, gallant and meritorious service at the Battle of the Wilderness.” Grant anticipated the terrible human cost of victory, and Porter appreciated his concern for needless death from hasty or incorrect decisions. Both abhorred what the war had become. Porter described the tragedy of the Wilderness campaign “as though Christian men had turned to fiends, and hell itself had usurped the place of earth.”

By late June, Union forces had been on the move and under fire almost constantly for six weeks. Following Cold Harbor in early June, and frustrated, they probed for another opening around Lee. In a letter to Sophie from Cold Harbor, Porter wrote that despite severe losses and several weeks of constant fighting, the men liked and trusted Grant in a way they had not McClellan. Also according to Porter, Grant was still working to rid the army of political generals, although it became a job even he and Lincoln together could not complete.

By mid-June, Grant was maneuvering between Petersburg and Richmond. Union confidence and ability to fight grew, as did casualty lists. The situation was precarious for both Grant and the Union. A major Federal reverse would jeopardize Lincoln’s chances for reelection as well as the momentum gained since early May. Porter sympathized with what Grant had to do militarily as well as politically. Still, he rejoiced at the progress.

Porter recognized that Grant and Lincoln were willing to make sacrifices necessary to ensure victory, although they disdained the suffering they ordered. About Grant, Porter wrote: “No warrior was ever more anxious for peace, and all of the general’s references to the pending strife evinced his constant longing for the termination of the struggle upon terms which would secure forever the integrity of the Union.”

Porter was present during Lincoln’s visit to Grant’s headquarters in June 1864. On that occasion, he learned Lincoln’s view of emancipation and its effect on American foreign relations. He also learned more about Lincoln’s simple and honest nature when Lincoln asked to visit a typical officer’s field quarters, which turned out to be Porter’s. Seeing various ordnance objects in Porter’s tent, Lincoln asked about the powder used in certain artillery shells. Porter explained. He was impressed with the president’s knowledge and interest in learning about something as mundane as powder grains from a young lieutenant colonel.

As a member of Grant’s military family and staff, Porter continued to observe and practice his mentor’s style of management. Grant let Porter and his staff undertake extensive duties and entrusted significant responsibility to them. The Virginia campaign also gave Porter many opportunities to see Grant in action and test his own courage in battle. Grant did not pamper his staff. He did not hesitate to ride along the front of battle with his aides or dispatch them on hazardous missions in the thick of the fighting as Grant kept probing around Lee’s left flank.

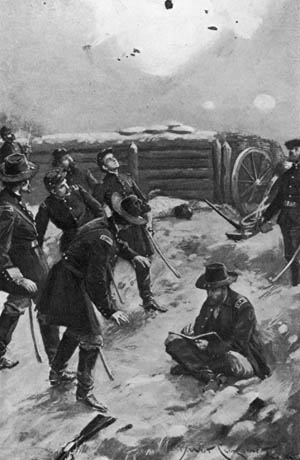

The Union Attack Devolved Into Chaos and Disaster

Ultimately lodged around Petersburg, south of Richmond, Union forces planted a huge mine beneath Confederate earthworks. On July 27, 1864 Porter was dispatched to Maj. Gen. Winfield Hancock, who commanded that point in the line, to personally deliver orders for the attack set for July 30. The explosion was timed for just before dawn to create a gaping hole in the Confederate lines in hopes of spreading Southern fear of more detonations and thus a general retreat. The explosives did not detonate on time, however. Union engineers bravely reentered the tunnel and reset the fuse, but the delay enabled the Confederates to erect a second line of defense. Finally, the mine exploded, blasting a huge crater in the Confederate works. But Union misfortune continued. Union troops were slow to hit the breach. When they arrived, the crater walls were too steep to allow rapid advance or retreat. Senior Union officers remained in the rear (one drunk) instead of leading their troops. The result was chaos, and some of the costliest and bloodiest combat of the war.

When the attack became a disaster, Grant decided to view the situation personally. He chose only an orderly and one officer, Porter, to accompany him on reconnaissance. Under direct and heavy fire, they entered the crater so Grant could communicate directly with officers there. Grant did nothing to countermand the orders of those brave junior officers; the real problems were in the rear with the senior officers. Confederate counterattacks forced Grant to withdraw. On Porter’s suggestion, they dismounted and returned to the Union lines. Having seen firsthand the situation in the crater, Grant stopped the attack. He saw no point in further futile loss of life by following a failed plan.

In the later summer and fall, Porter was an active participant in battles for Petersburg, Five Forks, and White Oak. His valor and actions were recognized on several occasions. On August 16, 1864 he was promoted to brevet lieutenant colonel “for gallant and meritorious services in action” at the Battle of Newmarket Heights. Porter’s abilities and reputation continued to grow, and Grant entrusted him with increasingly sensitive missions. In September 1864 Grant sent him to Atlanta to confer with Sherman and communicate Grant’s intentions. Porter also provided news to Sherman of Union actions designed to coordinate efforts against the shrinking Confederacy. While Grant put key points and the overall plan in a letter to Sherman, he informed the general that “Colonel Porter will explain to you the exact condition of affairs here better than I can do in the limits of a letter.”

At their first meeting, Sherman impressed Porter. They discussed the war in Virginia and elsewhere. Sherman asked Porter to communicate to Grant his intention “to strike out for the sea.” While both agreed Sherman could operate effectively by living off the land and cutting himself off from his base, neither worried that Grant would be unaware of the location and progress of Sherman’s force. Porter recorded that owing to the regular exchange of Union and Confederate newspapers across the lines in Virginia, “there will be no difficulty in hearing of your movements almost daily.” As a result of his understanding of Sherman’s plans and intentions obtained at their meetings that September, Porter frequently became the spokesman for Sherman when the latter’s activities were discussed by Grant’s staff.

Grant’s Trust in Porter was Well-Placed

Another example of Grant’s faith in Porter’s judgment arose when Grant was selecting a man to lead the assault on Fort Fisher. Porter recommended General Alfred Terry, whom he had known at Hilton Head and Fort Pulaski. On January 2, 1865 Grant sent for Terry and gave him the command. Terry subsequently captured the fort. Soon, Grant sent Porter to Fort Fisher to see what Terry had accomplished. Porter reported that the fort indeed had been a formidable place, and that Terry had done well. Grant’s trust in Porter’s judgment was well rewarded.

Porter was breveted colonel and then brigadier general of volunteers in February 1865. In March, he received two Regular Army brevet promotions, one to colonel, U.S.A., and the second to brevet brigadier general, U.S.A. Both Regular Army brevet promotions cited Porter for “gallant and meritorious services in the field.”

Also in March 1865, Porter had another opportunity to observe President Lincoln and learn more about prosecution of the war, national politics, and world affairs. Typical of both Grant and Lincoln, staff members again were allowed to participate in the meeting. With the end of the war in sight, they focused on planning for the future.

Following one series of discussions, Lincoln entered a tent in which Porter and some other officers were relaxing and settled in with them. He petted a stray kitten while chatting amiably. To Porter, such actions by the president surprised, pleased, and impressed him. His esteem for the man grew.

Ultimately, the siege at Petersburg came to a head. Lee attacked. Grant counterattacked. At the height of the fighting at Five Forks on the western end of the line, Grant needed frequent and precise appraisals of the situation from the front. He ordered Porter to spend the day with General Philip Sherman and the Union cavalry. Porter dispatched orderlies to Grant each half-hour throughout the whole day’s fighting on April 1. Significantly, as the battle progressed and Sherman maneuvered his cavalry seeking an opportunity to move around or through an opening in Lee’s defenses, Porter was empowered to suggest tactics to Sherman. “You know my views,” Grant had told Porter, “and I want you to give them to Sherman fully.” Grant knew and trusted Sherman. But he also recognized that Porter knew and understood his plans and intentions. When the fighting ended on April 2, with Union victory assured, Porter rode to Grant’s headquarters with the news.

Lee and Grant: The Fateful Surrender

Porter called the American Civil War “a great war tragedy.” After four years, it ended at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865. Porter was present at the surrender. He was fortunate to be one of few people inside the McLean House to witness the event. He took careful and copious notes (many verbatim) of conversations between Lee and Grant.

The proceedings were brief and businesslike, but cordial. No word of bitterness passed between the two commanders. Porter handed Grant a manifold book from which he read the articles of surrender. After discussing some of the language, Lee, who was attended by only one other officer, reached for a pen or pencil. Seeing that neither Lee nor his aide had one, Porter offered his own lead pencil to the Confederate general. Lee accepted the instrument and used it for the rest of the proceedings. At the conclusion of the meeting, he returned it to Porter.

Following the surrender, the mood was quietly excited. With the surrender of the South’s principal army, there was indeed reason to celebrate. But the human cost of the war had been so great and the end so sudden that both sides reacted almost numbly to the cataclysm at Appomattox. Even Grant was addled. After presiding at the surrender, he neglected to communicate the news to Washington. Riding back to camp, Porter realized the oversight and reminded Grant to report the surrender and its terms to the capital. Exclaiming that he simply had forgotten to do so, Grant immediately drafted and dispatched a telegram to the capital.

Grant asked Porter to accompany him to Washington on April 13, 1865, and from there to Philadelphia. Lincoln invited Grant to remain in Washington on the evening of April 14 to attend Ford’s Theatre. Mrs. Grant, however, was anxious to catch the 4 o’clock train, so Grant declined the invitation. Porter later wrote that when Grant returned to his hotel after meeting Lincoln, Mrs. Grant told him that during lunch “a man with a wild look” followed her into the dining room and stared at her. Grant was accustomed to people staring at him, so he gave the incident little weight until the Grants were riding along Pennsylvania Avenue to Union Station.

Assassination

A man on horseback riding in the same direction peered into their carriage. Mrs. Grant claimed it was the same man who had watched her at lunch. Before they reached the station, the man reversed direction, passing them a second time. Before their train reached Baltimore, someone tried to enter the car in which Porter and the Grants were traveling. He was deterred because the conductor had locked the door to the car to ensure the Grants’ privacy. The Grant party reached Philadelphia that night. At a late supper around midnight, a telegram informed Grant that the president had been shot earlier that evening at Ford’s Theatre.

Porter believed Grant’s life was in danger on April 14. Porter and the Grants thought photos of John Wilkes Booth published after the assassination strongly resembled the man who spied on the Grants on their way to the station. In November 1868, Grant received an anonymous letter, ostensibly from the man who tried to enter the railway car Grant had taken to Philadelphia. The writer claimed to have been an accomplice of Booth assigned to kill Grant. The writer noted that the door to Grant’s railway car had been locked, a fact known to few people.

A final aspect of Porter’s involvement with Lincoln’s assassination was his appointment to the court assigned to try the conspirators. The defense, however, claimed Porter would be biased because he was on the staff of an intended victim. Porter was excused from the jury.

The Civil War was for Porter and his generation the most formative experience of their lives. When Porter reflected on the years of battle, he recognized “the terrible realism of relentless war.” From 1887 to 1897, Porter collected documents, analyzed published materials, and wrote many letters inquiring into recollections of Civil War events. He also studied his own “elaborate” notes from 1863 to 1865, with a goal to publish a thorough and exact account of the Virginia campaign with Grant. Portions of Campaigning With Grant appeared as articles in Century Magazine in the late 1880s and mid-1890s before Porter finally collected them into one volume. He finished Campaigning With Grant just before he departed for Europe in spring 1897 as U.S. Ambassador to France. He dedicated it “To my comrades of the Union Armies whose valor saved the Republic.”

From 1866 to 1868, Porter served under Grant in Washington helping with the dissolution of Union armies and inspecting military posts around the country. For a time he was assistant secretary of war to Grant. In the winter of 1868-1869, he was dispatched south to quell Ku Klux Klan wars in Arkansas and Louisiana. Porter struck a raw nerve with the Klan, precipitating a letter to him signed “Beware—KKK.” It warned: “Your time is short. Thus far you have been spared, but neither the army, the navy nor Congress can protect you longer, nor for one hour defer the just retribution in store for you when the time to strike arrives.”

The Bloody War Disillusioned and Heavily Influenced Porter’s Life and Career

From 1869 to 1872, Porter served as executive secretary to Grant, who had been elected president. But Porter was unused to Washington politics. By 1872, his experiences disillusioned him and he decided to leave the administration after Grant’s reelection, although he reluctantly took leave of Grant himself. In 1872, he became vice president of the Pullman Palace Car Company. In that and other railway and business ventures, Porter became a millionaire. He also was active in civic affairs and politics, particularly in New York, raising large sums to finance William McKinley’s 1896 election.

From 1897 to 1905, Porter served as U.S. Ambassador to France. During those years, he was involved with Spanish-American War diplomacy and the complex international events of that era when the United States emerged as a world power. In 1907, he was U.S. delegate to the Second Hague Peace Conference. An advocate of naval preparedness before WWI, he served as president of the Navy League of the United States from 1909 to 1915.

But all his life, Porter retained memories of the hardship, suffering, destruction, and death that he witnessed, lived, and survived from 1861 to 1865. The Civil War influenced him through the remainder of his life and career in business and diplomacy. His two great heroes were two men he knew, one exceptionally well: Lincoln and Grant. Horace Porter died in 1921.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments