by Harold E. Raugh, Jr.

War correspondents are relatively new to history. The Crimean War (1854-1856), pitting Great Britain, France, Turkey, and Sardinia against Russia, was the first conflict in which an organized effort was made for civilian correspondents reporting news directly to the civilian population of the home country. Many senior British Army officers were very distressed by this development, because they no longer held a monopoly of presenting news through their correspondence with their governments.

[text_ad]

The war correspondent was generally looked upon with resentment, suspicion, and even disgust by senior British Army officers during the Victorian era. Field Marshal Earl Frederick S. Roberts held a more positive view of war correspondents and was very conscientious in providing them accurate and timely information. “I consider it due to the people of Great Britain,” declared Roberts, “that the press correspondents should have every opportunity for giving the fullest and most faithful accounts of what might happen while the army was in the field.” Field Marshal Viscount Garnet J. Wolseley, on the other hand, abhorred war correspondents, believing them to be “those newly invented curses to armies, who eat the rations of fighting men and do no work at all.” It seems Wolseley’s attitude toward war correspondents was more prevalent than Roberts’ opinion in the British Army during the second half of the 19th century. Wolseley, however, cleverly took advantage of these “curses to armies” in unorthodox ways and to great effect in a number of his many campaigns.

Our Only General

Wolseley, born in 1833 and commissioned in 1852, dominated British military affairs during the second half of the 19th century to such a large extent that he was known as “our only General.” After distinguished service in four campaigns (Second Burma War, Crimean War, Indian Mutiny, and Third China War), in 1861 Wolseley was ordered to Canada. He began to devote himself more to the study of the profession of arms and testing his theories of military organization and training.

After his promotion to full colonel in 1865, Wolseley started collecting and collating practical military information that would answer any question in the field for regimental officers and soldiers and would supplement the Queen’s Regulations and the Field Exercise. Wolseley, drawing upon his wealth of knowledge and experience gained through gallant service in four campaigns, included “tables of weights and measures … menus for Irish stew, exchange rates for foreign currency” and information on the care and feeding of elephants, burials at sea, the management of spies, and myriad other subjects in the Soldier’s Pocket Guide for Field Service, published in 1869. In this book, Wolseley also recommended that generals give false information to war correspondents in order to deceive the enemy.

In 1870, Wolseley was appointed to his first independent command. Called the Red River Expedition, this operation was noted for its careful preparations and logistical planning. Three years later, while Wolseley was serving at the War Office, a large Ashanti army invaded the British Protectorate of the Gold Coast (today’s Ghana). Politicians were reluctant to commit British troops to such a pestilent area—West Africa was then considered “the white man’s grave”—but in August 1873 the government appointed Wolseley to command an expedition to whip the Ashanti army and restore order in the area.

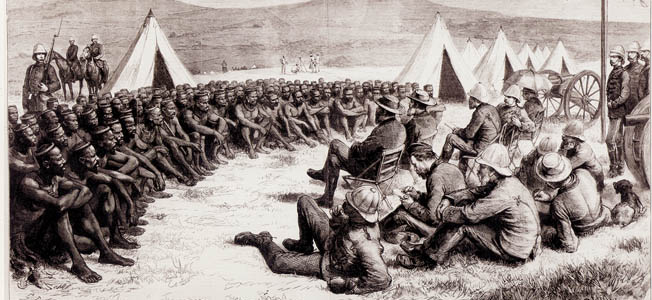

On September 12, 1873, Maj. Gen. Wolseley, his staff, and others set sail from Liverpool on board HMS Ambriz. On the same ship were a number of prominent war correspondents, including Winwoode Reade of the Times, G.A. Henty of the Standard, and basking in the fame of having recently found Dr. Livingston, Henry M. Stanley from the New York Herald. While personally despising journalists and considering them a “race of drones,” Wolseley may very well have endeavored to cultivate good relationships with these reporters, knowing they had the ability, through their newspapers, to portray him and his campaign in a positive light.

Wolseley arrived at Cape Coast Castle on the Gold Coast in October 1873. Immediately after landing, he and his staff began recruiting local levies, enlisting local “spies” and interpreters, and making logistical arrangements for the expected January 1874 arrival of the main body of British troops. His plan was to keep his troops in the country for as short a time as possible, thereby reducing the chances of disease and casualties.

White Men Dare Not Go Into The Bush

During this time Wolseley also sent summons to the local Protectorate chiefs to attend a meeting to discuss cooperation and local strategy against the Ashanti. British prestige, however, was low at this time, owing somewhat to the fact that the Ashanti and their confederates had never before encountered British military determination and might. The contemptuous response of one headman was, “I have smallpox today, but I will come tomorrow”—but he never did.

Lieutenant Colonel Evelyn Wood, one of Wolseley’s subordinates, asked the chief of the village of Esamen, an Ashanti ally, to meet him in nearby Elmina. The Esamen leader brazenly replied, “Come and get me; white men dare not go into the bush.” Many of the chiefs were Ashanti sympathizers and were confident the British would never risk marching through the dense jungle to the villages. As a result, one of Wolseley’s loyal native messengers was decapitated and mutilated and his body exposed on a beach, both as an insult to the British and as a fetish charm to keep them away. The British were not to be outdone, as Wolseley wrote to his wife on October 8: “We had a man hanged here this morning from the lighthouse tower on Fort William, so all the world could see the execution; the town … seemed as well pleased as if a balloon had been sent up for their amusement.”

Such blatant native insolence was unacceptable to Wolseley, and he determined to destroy Esamen and several nearby towns. This would chastise those natives loyal to the Ashanti and demonstrate the decisiveness and power of the British. An assault on this inland village would also cut off the Ashanti from their supplies, which came from the coast, and hopefully force them to withdraw to their own territory farther in the interior. Moreover, British-controlled native intelligence had pinpointed Esamen as a center of enemy communications.

Wolseley knew it would be difficult to conceal troop concentrations and movements in such an environment. At breakfast on October 12, in the presence of war correspondents, Wolseley mentioned casually that a British detachment near Accra—far up the coast to the east of Cape Coast Castle—was in danger of possible encirclement by the Ashanti and that he might have to go there to see the situation for himself. The following morning, Wolseley, again at breakfast with a group that included the war correspondents, stated the situation had become desperate and that he would soon sail for Accra. The zealous war correspondents, eager to get a scoop on the situation and each other, ensured their home newspapers were informed and that the word was spread in the area that Wolseley and a number of soldiers would soon be departing for Accra.

Woseley’s Ultimatum and Deception

On October 13, Wolseley sent an ultimatum to the Ashanti king giving him 30 days to withdraw his army from the Protectorate, release all hostages, and guarantee indemnification. Wolseley warned him to expect “full punishment” if these conditions were not met. This helped lull the Ashanti into a sense of temporary complacency, believing they would not be attacked by the British for at least a month, if at all.

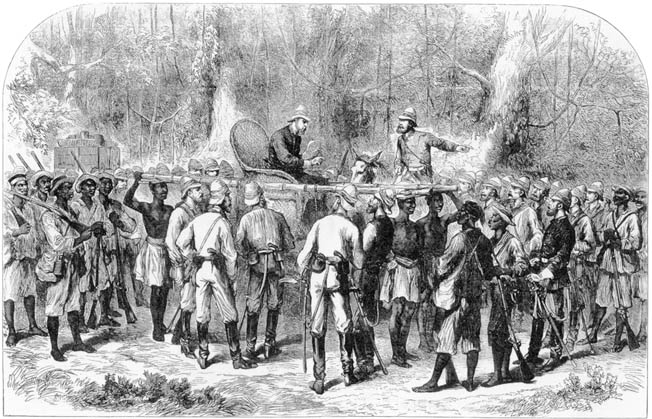

That evening, Wolseley boarded a gunboat with his staff, a large infantry force, and two war correspondents (one of whom was Reade, and the second was probably Henty). Ostensibly sailing to Accra in the east, the ship instead sailed west to Elmina, which was only a short march from Esamen. Wolseley landed at Elmina at 3 am, and after he linked up with Wood and his native soldiers, the entire force marched to Esamen. A short skirmish ensued, with the demoralized and defeated Ashanti warriors fleeing and abandoning their town. Esamen was razed, and Wolseley’s column returned to the coast and destroyed a number of other villages. Only a few select officers and others had been privy to Wolseley’s actual destination and plans.

While the battle at Esamen was a relatively small affair, it was significant in a number of ways. The imbroglio at Esamen destroyed the myth of Ashanti invincibility. It also showed foes and native friends alike that the British had the ability and audacity to march through and fight in the densest jungles and swamps. While the Ashanti would not be totally defeated and the campaign not brought to a successful conclusion until February 1874, the engagement at Esamen was a turning point in the operation. Wolseley’s initial success on the Gold Coast can be attributed directly to following the advice he had given in the Soldier’s Pocket Guide for Field Service: to intentionally feed false information to war correspondents, which in turn would deceive the enemy. Wolseley was said to have been “immensely pleased” with the way his ruse had misled the correspondents—and his adversary. The war correspondents who missed the first encounter of the campaign were probably less than pleased. As a result of his relatively quick and inexpensive success in the Ashanti war, Wolseley was showered with honors upon his return to England.

Victory, Honor (And a Promotion)

Eight years later, in 1882, Wolseley was selected to be the Adjutant General at the War Office in London. At this time the political and financial situation in debt-ridden Egypt was precarious and volatile. Under considerable pressure, the Khedive (Viceroy) of Egypt appointed British and French controllers-general of Egyptian finance. Such external domination over Egypt’s internal affairs caused considerable resentment, and in January 1882 Egyptian Colonel Ahmed Arabi led a rebellion that threatened to overthrow the Khedive.

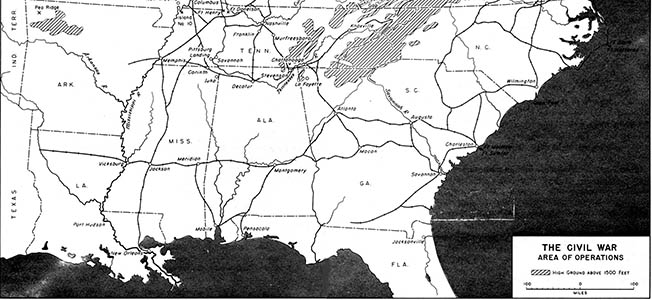

After a number of provoking actions and the killing of Europeans in Alexandria, the British government then decided Arabi and his destabilizing influence must be eliminated. At the height of his abilities, prestige, and popularity, Wolseley was the government’s first and natural choice to lead the British force to crush Arabi. Wolseley and troops of the expeditionary force, which eventually numbered over 40,000, departed England in early August 1882. While en route, Wolseley, who landed at Alexandria on August 15, assessed the situation and developed a campaign plan that he intended to execute as soon as the entire force was assembled. This was scheduled for August 19. The objectives of the campaign were to seize the Suez Canal to ensure the maintenance of free passage, destroy Arabi’s army, and capture the Egyptian capital of Cairo.

On his first day in Alexandria, Wolseley coordinated the campaign plan with Admiral Sir Beauchamp Seymour. In order to seize the Suez Canal before Arabi was able to shift his troops from Alexandria to defend the canal or to block it and then swiftly capture Cairo, Wolseley knew he would have to take advantage of his force’s superior mobility and amphibious capabilities. He decided to shift his base of operations to Ismailia, on the western side of the canal, and attack westward to Cairo, parallel to a railway and the all-important Sweetwater Canal. It was also the shortest overland route to Cairo as well as to the main Egyptian camp at Tel el-Kebir. This plan would permit Wolseley to avoid fighting through the countless flooded irrigation ditches of the Nile Delta or through the treacherous desert west of Cairo.

In order to deceive Arabi about British intentions, Wolseley devised a cover plan for the British to conduct a coordinated ground and naval attack on the Egyptian forts at Aboukir Bay, some 30 miles east of Alexandria and the scene of Nelson’s defeat of Napoleon’s fleet in 1798. Wolseley issued guidance to Lt. Gen. Sir Edward Hamley, commanding the Second Division, to develop a plan for his division to move overland from Alexandria and attack in conjunction with those troops reportedly scheduled to disembark and attack at Aboukir Bay.

“The Press Has Become a Power Which a Man Should Try to Manage for Himself.”

On August 17, 1882, Wolseley—in a manner reminiscent of his deception scheme involving war correspondents during the Ashanti war—had a staff officer brief the assembled news-hungry reporters that a British attack on Aboukir Bay was imminent. Press censorship was lifted. To reinforce the ruse, one of Wolseley’s intelligence officers, falsely using the name of its correspondent, telegraphed the Standard denouncing as completely false the rumor that the British would violate in any way the neutrality of the Suez Canal. Because Alexandria was swarming with Egyptian spies, Wolseley knew the seemingly credible misinformation would soon be on its way to Arabi. Wolseley had again put into practice his philosophy that “the Press has become a power which a man should try to manage for himself.”

On August 18, the Brigade of Guards and other British troops re-embarked on transport ships, apparently bound for the assault on the Aboukir forts. At that time, Wolseley wrote to his wife: “We start from here to-morrow at noon for Aboukir Bay, where the fleet and all the transports carrying the first Division will anchor at 4 pm to-morrow to pretend landing there during the night to attack Arabi’s position in front of this place on Tuesday morning. Everyone here believes we intend doing so: only about three people amongst the soldiers are in the secret, and I have completely befoozled the ‘press’ gang, who have, I know, telegraphed home that we mean to land at Aboukir. I suppose they will be furious when they find how they have been taken in, but if I can take them in, I may take in Arabi also. On Sunday evening I hope to be at Ismailia.… It is no easy matter getting 30,000 men to a point with only a canal as a means of approach.”

The First Division arrived on schedule and joined the British armada anchored outside the Alexandria harbor. Plans and coordination had been veritably flawless. At noon the following day, the powerful British fleet of eight ironclads, ostentatiously belching smoke and guarding 17 transport ships and two small dispatch boats, sailed east to Aboukir Bay. The British fleet anchored in Aboukir Bay, its purported destination, four hours later. The British warships appeared to prepare for action, and the Egyptian gunners stood by their guns in anticipation of a heavy naval bombardment.

Selling Deception

At nightfall on August 19, the two small craft from the British fleet approached the shore and opened fire. To reinforce the deception, Wolseley tried to get Seymour to fire dummy rounds in his naval guns. The admiral, however, refused to violate naval customs by participating in such an unorthodox demonstration. Impressed and eager war correspondents on the ships, however, wrote that they had witnessed “the great bombardment” at Aboukir Bay. The naval firing was in fact a subterfuge, because the fleet, under cover of darkness and while seemingly engaged in a naval bombardment, weighed anchor and sailed farther east. The stunned Egyptians at Aboukir woke up the following day to see that the British armada was gone. The British ships arrived at Port Said at the northern entrance to the Suez Canal after sunrise on August 20.

Hamley, not privy to Wolseley’s actual plans, remained at Alexandria with a sealed packet and instructions not to open it until the morning of August 20. Wolseley reveled in his ruse, and wrote to his wife: “It is very amusing that General Hamley who commanded the 2nd Division, and Generals Alison and Wood who command the two Brigades of that Division, are under the firm conviction that we mean to attack here [Aboukir Bay] on Sunday and that they are to take part in the attack: I am leaving sealed orders to be opened by Hamley at daybreak on Sunday morning in which I tell him the whole thing is a humbug and that my real destination is the Canal.”

Hamley opened his sealed packet as directed, and read a letter from Wolseley: “I do not mean to land at Abukir [sic]; my real destination is Ismailia. I hope to reach that place at about 4 pm on Sunday next. We make our demonstration all the same at Abukir [sic] tomorrow, and I hope it may have the desired effect of imposing upon Arabi and his friend Lesseps [Ferdinand de Lesseps, the Frenchman and builder of the Suez Canal, resented the British and refused to cooperate with them on this operation].… When you open this, keep the news to yourself, tell no one, and do nothing beyond showing as many men as you can conveniently in Arabi’s front, and giving him as many shells from any of your guns of position that can reach him in his works. I do not even telegraph the news of my intended movements home until I have reached Port Said myself, which I hope to do before daylight on Sunday morning.”

Backlash From the Press

While Hamley did as he was told, it seems he—and many of the war correspondents—were furious and indignant at having been the “victim” of Wolseley’s deceptive “humbug” on the field of battle. Oddly, the newspapers were quick to forgive a victorious general; Hamley never did.

By the time Wolseley arrived at Port Said shortly after sunrise on August 20, British naval forces had secured the entire length and key points of the Suez Canal. As soon as Wolseley arrived at Ismailia the following day, he began preparations for the final advance on Cairo. Pushing out from Ismailia, Wolseley’s units had a number of skirmishes before Hamley and his division rejoined the main force at Ismailia on September 1.

It took the British forces a few weeks to inch their way over the hardened desert and under the scorching heat to the outskirts of the heavily fortified Egyptian camp at Tel el-Kebir. Then after careful planning and reconnoitering the enemy positions, Wolseley decided to conduct an almost-unprecedented large-scale night march and surprise and assault the Egyptian position at dawn.

At 3 pm on September 12 the soldiers were told they would move out that night and attack the Egyptian stronghold of Tel el-Kebir. To deceive any observing Egyptian spies, the British soldiers did not take their tents down until after sunset. They then marched silently to assembly areas. At 1 am, the British forces, numbering some 17,401 men and 61 guns, began their stealthy march across the trackless desert.

Shortly before dawn, a single shot was fired from the Egyptian positions, and this alerted the defenders. The British then fixed bayonets and assaulted Arabi’s fortifications. Fighting was fierce, often hand to hand, with men hacked or stabbed to death, or blown apart by cannon. But the Egyptians, caught off guard by Wolseley’s night march and surprise assault, were no match for the stalwart and disciplined, well-led British soldiers. As red blood soaked into the yellow sand, the battle ended after only 35 minutes.

The “Tidiest War Ever Fought by the British”

A rapid pursuit of the vanquished enemy followed, and Wolseley entered Cairo two days later. The war was over, with relatively few casualties and minimal expense. Wolseley believed his Egyptian campaign, complete with his “humbug” of a ruse that deceived the war correspondents—and Egyptians—“was the tidiest little war ever fought by the British army in its long history.” It probably was.

Wolseley’s outstanding successes at Tel el-Kebir, and during the Egyptian campaign as a whole, marked the zenith of his career. Wolseley later led the unsuccessful 1884-1885 expedition to rescue the besieged Maj. Gen. Charles Gordon in Khartoum. Promoted to field marshal in 1894, Wolseley became British Army Commander-in-Chief in 1895, only to find the position and its authority considerably weakened. Britain’s “only General” retired in 1900 and died 13 years later.

Wolseley was undoubtedly a successful general and was a master of the small colonial wars that were fought throughout Queen Victoria’s long reign. He was aggressive, courageous, farsighted, and a superb planner and leader. He also did not allow himself to be fettered by orthodoxy. During at least two campaigns—the Ashanti campaign of 1873-1874 and the Egypt campaign of 1882—Wolseley fed false information to war correspondents, which in turn deceived the enemy as to his actual intentions.

During both campaigns, Wolseley’s ruses led directly to tactical victory and campaign success. It was fortunate for Wolseley, and for Great Britain, that the war correspondents who accompanied him on his campaigns had not read his Soldier’s Pocket Guide for Field Service, in which Wolseley had written, “These gentlemen, pandering to the public taste for news, render concealment most difficult, but this very ardour for information a General can turn to account by spreading fake news among the gentlemen of the Press, and thus use them as a medium by which to deceive the enemy.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments