By James K. Swisher

The brightly uniformed soldiers that George III of England dispatched to subjugate the rebellious citizens of his North American colonies were at that time possibly the world’s best. Tempered in constant European warfare, and accustomed to coolly cowering native insurrections with a handful of bright red coats, their successes had bred an easy arrogance that sometimes fostered a dangerous underestimation of the fighting abilities of their enemies. Perhaps nowhere else did this become more apparent than the Battle of Kings Mountain.

This attitude was most pervasive among the pampered, vain, young field officers who led England’s elite regiments. Purchasers of their rank, these arrogant sons of the gentry were insufferable in barracks, boorish amid the drawing salons of London, but just as often brave beyond belief in actual combat. Throughout history, however, gross disrespect for the peculiar abilities of one’s opponents has led to startling military reversals, and this blind spot was not lost on British field officers.

Thin, oval-faced, young Patrick Ferguson, a handsome, intelligent officer and extraordinary gentleman, was as guilty as his compatriots in his assessment of American military abilities. On several occasions Ferguson had said, “A volley and a dash of cold steel was just the dose to cause rebels to break, and once on the run such inexperienced troops would never rally.”

Ferguson and his fellows, all competent professionals, simply never understood the methods of life and warfare that had developed among the Scots-Irish and German-Swiss settlers of the southern Appalachian uplands. Schooled in intermittent combat with marauding Indians, these crafty backwoodsmen learned the value of using cover when available, to retreat when such was advantageous, and to fall with unrelenting vengeance when an opponent’s weakness was unveiled.

Their battle lines were fluid, ebbing and flowing in constant change; thus hard to attack and more difficult to defend against. Fiercely independent and virtually immune to intimidation, they feared no man, respected only those who earned such honor, and granted mercy to few. Men were judged by their courage and fighting prowess. Combat was usually to the death.

W.J. Cash, who spent a lifetime studying the Southerner, postulated that two premises seemed to govern the life of an Appalachian frontiersman. The first was that he possessed an intense distrust of and aversion to any authority beyond an absolute minimum. Second and correspondingly, he retained a tendency to violence that lay just beneath the surface and was most often voiced in the boast “that he would knock hell out of whoever dared to cross him.” These two traits contributed greatly to the superb fighting skills they demonstrated when agitated. Underestimation of the grit and determination of these rebel settlers could be deadly.

Of Scottish birth, young Patrick Ferguson grew up amid the bustling, exciting city of Edinburgh where his solicitor father, James Ferguson, or Lord Pitfour, served as Lord Commissioner. Ferguson’s mother, Anne Murray, was of an equally noble Scottish family and her brother, Brig. Gen. James Murray, who advocated a military career for Patrick, had replaced the dying Wolfe on the “Plains of Abraham.”

With his summers spent exploring the city, especially the great stone castle frowning down from its lofty perch, Ferguson became enthralled with the pomp and panoply of the Scottish regiments parading daily from their headquarters at Edinburgh Castle. An impressionable youth, he listened breathlessly to fanciful tales of battles won and lost, as spun by the bearded old veterans. He attended military academy at Wolich and joined the 2nd or Royal North British Dragoons as a coronet or sublieutenant when barely 14.

Soon the slightly built youngster joined his regiment in Germany, fighting on the plains at Minden against the powerful French cavalry. He was commended for reckless bravery on at least two occasions but subsequently fell seriously ill, as did most of his regiment, from the effects of foul drinking water. He had probably contacted a mild case of typhoid and was posted back to Edinburgh Castle in 1762. When his illness persisted Patrick was forced to resign from military service.

By 1768, his health much improved, Ferguson again joined the King’s service. He purchased a captain’s commission in the 70th Regiment of Foot. Performing admirably on expeditions to Grenada and Tobago, he also campaigned against the revolting Caribs on the island of St. Vincent. In 1773 he was assigned to garrison duty in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Falling ill again, he was posted back to Edinburgh. Extremely frustrated, he feared for his army career which, marked by excellent service, appeared doomed by poor health.

While in barracks, the industrious Ferguson began experimentation with a breech-loading rifle, originally of French design. His inquisitive intelligence, supported by the resources of his family, provided ample impetus for such a study of weaponry. Ferguson altered the original design’s breech block, reconfiguring the breech in such a way as to increase containment of gases released upon discharge. This, in turn, improved the muzzle velocity, range, and accuracy of the weapon. The ramming step was eliminated, increasing speed in volley fire and allowing the weapon to be loaded while kneeling or even in prone position, two factors of high military significance.

Ferguson, who already was considered the best marksman in the King’s service, demonstrated his rifled musket at Woolwich Arsenal on April 27, 1776 before highly skeptical British authorities. He started firing at a rate of four shots a minute, then executed a drill that consisted of firing and reloading while marching toward a target. All of Ferguson’s evolutions were performed at a target distance of more than two hundred yards, well over twice the range of the Brown Bess. His weapon completely outshone the performance of the Brown Bess musket, then issued to all infantry regiments. The weapon so impressed the King and several ministers that one hundred were ordered and Ferguson was assigned to supervise production.

New Rifle Design To Be Put To Test Against The Rebels

During the following winter a company of light infantry was organized, outfitted with green uniforms, and equipped with the new rifles. Captain Ferguson was placed in command and the unit sailed for America in March of 1777. The new weapon would be tested in the forests against colonial Rebels, who would soon demonstrate they had developed similar firearms.

Ferguson’s new rifle saw first action at the Battle of Brandywine near Philadelphia. Near Chadds Ford the riflemen were engaged as skirmishers in a tough delaying action. The results were encouraging but the company suffered heavy losses and Ferguson was wounded, a musket ball shattering the elbow joint of his right arm. He argued vociferously and successfully with physicians determined to amputate his limb, although the arm was forever useless. While he was convalescing the company was disbanded by a jealous Lord Howe. The soldiers were disbursed to their respective regiments and the Ferguson rifles stored. Only Ferguson and several of his subordinates retained the unique and potent breech loaders.

Meanwhile, however, an eerie tale of Ferguson and a chance encounter with a grandly uniformed and unidentified American officer spread rapidly through the army. As the story went, Ferguson and several riflemen were concealed in heavy woods near Germantown when two colonial officers in blue and green rode into view, approaching within one hundred yards. One of the officers, a large man astride a bay horse, wearing a large cocked hat, seemed of commanding presence and Ferguson stepped forward from cover, challenging the intruder to surrender. But the American, motionless, stared at Ferguson for several minutes, then deliberately and slowly turned his back and rode away. Despite the pleas of his riflemen, Ferguson disdained the easy shot and forbade his men to open fire.

The American was likely George Washington, who had reconnoitered the area that particular morning. Had the British officer taken the easy rifle shot one can but wonder on the outcome of the conflict, or even the future history of the United States. When told that his encounter may have been with the commander of the Rebel Army, Ferguson remarked: “I am not sorry that I did not know at the time who he was.”

Despite the serious nature of his wound, Ferguson refused to resign, teaching himself to write, shoot, and handle a sword left-handed. Soon he was commanding a unit of Loyalists, raiding privateer bases along the New Jersey shore. During a raid on Little Egg Harbor, Ferguson demonstrated his ability to conduct combined land-sea operations, employing tactics of unusual and innovative style. His handling of light infantry became a model for the army.

Ferguson also became accustomed to dealing with deserters, turncoats, and double agents. His men were involved in a number of marauding expeditions to capture or burn out turncoat Loyalists. He zealously strove to avoid hardships to innocent individuals but was unrelenting in dealing punishment to those opposing the Crown. Concurrently he developed strong rapport with his New Jersey Loyalists, and on October 25, 1779 was promoted to major in the Highland Light Infantry. Extremely fair, considerate, and personable, he was one of a handful of British officers who earned the respect of those ill-fated colonists who remained loyal to the King.

Ferguson Heads South To Rally Loyalists

Late in 1779, the conflict changed drastically. Sir Henry Clinton, the British Commander-in- Chief, became frustrated with the stalemate in the New York area and decided to open a campaign in the southern colonies. The British wanted to force a separation of Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina from the other colonies and possibly recover them for the King. The principal southern seaport, Charleston, was captured after a brief siege, and Maj. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis was assigned to command the southern British Army. While not provided a large force of British regulars, Cornwallis was initially encouraged by the numbers of southern Loyalists flocking to his colors.

Major Patrick Ferguson, with his reputation as a leader of Loyalists, was ordered south to strengthen Cornwallis accompanied by about one hundred members of his New Jersey Legion. Cornwallis increased Ferguson’s command with the addition of a legion of Southern Loyalists and about two hundred Hessians.

But his initial action, at McPherson’s Plantation, was almost fatal for the young major. Ferguson’s men approached an enemy camp after nightfall and, finding it deserted, decided to await the return of its occupants. At dawn a large British force mistakenly attacked and Ferguson, fighting desperately with three assailants, was wounded by a sword slash to his left arm. With his right arm already useless, Ferguson became virtually defenseless as he sat upon his horse, reins in his teeth, issuing orders by means of a silver whistle he wore on a lanyard about his neck. Then, in another turn of fortune, Ferguson was recognized and the attack halted.

Cornwallis was pleased to have the gentlemanly officer join his command, even though he was fully aware of Ferguson’s impetuous and independent nature. Ferguson was affable, witty, and socially gregarious. Irresistible and courtly to the young ladies of Charleston, Ferguson developed a reputation as somewhat of a rake. He would sit and discuss the political situation with any colonial willing, always trying to convert the dissenter to his position.

He absolutely refused to make war on women and children. On one occasion, near Monk’s Corner, when three soldiers mistreated several patriot ladies, Ferguson insisted they be summarily hanged. The incident soured his relationship with Colonel Banastre Tarleton, with whom he was at the moment exercising joint command and who disagreed vehemently, attempting to dismiss the incident. Ferguson soon grew to dislike and distance himself from the cocky, red-headed British cavalryman.

Cornwallis slowly strengthened his position in South Carolina by fortifying a number of strongpoints in strategic locations about the colony. Establishing his command center at Camden, he utilized Ferguson and Tarleton as leaders of flying columns, which attempted to reduce the effectiveness of American guerrilla leaders such as Thomas Sumter and Francis Marion. Ferguson was dispatched west to the crucial fort at “96” with his New Jersey Legion, partly to recruit additional Loyalists. His force was also responsible for screening Cornwallis and his main force from any surprise foray from the mountains.

Ferguson worked feverishly training his Loyalist infantry as rumors spread of patriot militia rising in the mountains. He was impatient to bring his recruits to the level at which he could use them to investigate these rumors.

A newly appointed American commander in the south, portly Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, marched south in early summer, 1780, driving directly at Cornwallis’s principal base. Despite a heavy advantage in numbers, Gates was routed at Camden in one of the most complete defeats of the war. When Tarleton surprised and defeated Colonel Thomas Sumter at Fishing Creek shortly thereafter, momentum swung swiftly to the redcoats.

Cornwallis increased his expectations and decided to move into North Carolina with a three-column offense that could sever the three southern colonies from the remainder of their American sisters. He would move with his main force via Charlotte Town and Salisbury, while a column from Charleston advanced up the coast to envelop Wilmington. A third force under Patrick Ferguson would slowly advance north abreast the eastern foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, protecting the left flank.

Ferguson set out with his one thousand Loyalists on September 7. He marched to and fro across northwestern South Carolina for several weeks in frustrated attempts to entrap small parties of patriot militia. Lacking adequate supplies, Ferguson requisitioned beef cattle wherever he located them, from both Whig and Tory farmers. He burned barns, even houses, of staunch Rebels as this civil war in the Carolinas grew increasingly bitter and harsh.

But remaining in character, Ferguson was gallant and polite in his encounters with female Rebels. As volunteers flocked in, a number of camp followers joined Ferguson’s little army. Two of these ladies became servants of the commanding officer: Virginia Paul, who became his cook; and Virginia Sal, a comely redhead, who washed Ferguson’s uniforms, among other chores.

His Loyalist column crossed the North Carolina border and marched to Gilbert Town (present-day Rutherford) near the Broad River. While there, Ferguson rashly issued an edict that in retrospect he must surely have regretted. But he was dealing with guerrilla bands which gathered for harassment, then faded away. His imperative order was an attempt to discourage these groups from gathering, and to intimidate the uneducated backwoodsmen through warnings of the consequences of their continued active participation in the conflict.

He dispatched a messenger to the mountain men, warned them: “If they did not desist from their opposition to British Arms and take protection under his standard, he would march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay waste their country with fire and sword.”

Ferguson’s message, however, had a diametric effect from its intentions. In fact, seldom in military history has such a brief message served as catalyst for such definitive action on the part of one’s opponent. The proud, self-sufficient mountaineers received the British message as a gauntlet flung before their faces, challenging them to combat. For one who knew the values of these hardy folk, their reaction was predictable.

In violation of the Proclamation of 1763, which limited colonial expansion to the crest of the Alleghenies, the resolute settlers had continued to stream through the Valley of Virginia and settle in the vales, valleys, and hollows of southwestern Virginia, and eastern Tennessee and Kentucky. Cutting all ties, these adventurous folks undertook a life of independence, based on their own resources, removed from the strings of any authority. Hospitable and kind in nature to the traveler, when threatened the thin veneer of civility disappeared, revealing their propensity for sudden violence.

Aware of the fratricidal war raging in the East, these mountain folk were inclined to remain at home, tending to their own substantial needs. Mildly anti-British, whom they blamed for the Indian uprisings, they were still too busy with survival to enlist in colonial armies. It took a challenge such as Ferguson’s to galvanize these simple men into action.

Sycamore Flats or Shoals on the Watauga River in present-day Tennessee was chosen as the gathering place. The message to assemble swept up and down the mountain range. Soon the buckskinned, moccasin-wearing woodsmen began to assemble, many with their families. Rotund, red-headed Colonel William Campbell, his ancestral broadsword strapped to his back, rode in with two hundred men from Washington County, Va., soon to be followed by two hundred more. Colonel Issac Shelby and Colonel John Sevier marshaled more than five hundred from the mountain coves of Kentucky and Tennessee. Several hundred North Carolinians followed Colonel Charles McDowell marching westward over the mountains to Sycamore Flats.

Hundreds of campfires twinkled in the night by the river as this largest gathering in recent memory was enjoyed by children and wives. Backwoodsmen smoked their pipes, traded lies, and awaited the word to march. On September 26, after a militant sermon by Reverend Samuel Doak in which he invoked the sword of the Lord and Gideon, and kissing their wives goodbye, the long file of riflemen and their horses turned east and began to ascend the mountains, serious in demeanor and purpose.

Armed with long-barreled Pennsylvania or Dickert rifles, knife and tomahawk in belt, they rode up Gap Creek and camped at Resting Place or Shelving Rock the first night. Then they marched up Toe River, and began the long ascent of Roan Mountain, which was the crest of the mountain range at 6,300 feet. Atop Roan, the first snows of winter were inches deep as the men dropped over the crest before camping on the night of September 27.

The following morning, aware of two desertions, the mountain men split into two divisions as precaution against ambush, Campbell leading his Virginians down into Turkey Cove while the remainder filed into North Cove. Scouts rode in with information on Ferguson’s location, and the marchers reassembled at Quaker Meadows where friendly locals had provisions ready for their use.

Meanwhile, Ferguson, falling back from Gilbert Town, had crossed the Broad River and was within 50 miles of Cornwallis’s main army at Charlotte. He continued to recruit, warning of the dire consequences of an invasion by the mountain men. When he learned from two deserters of the arrival of the Rebel force, he fell back slowly, far too proud to retreat.

The Battle of Kings Mountain: How Ferguson Fell

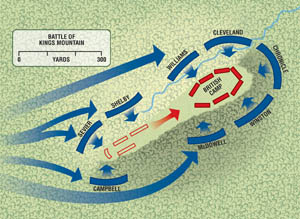

On October 6, Ferguson marched his men 16 miles to camp atop a hill known locally as Kings Mountain, which rose about 60 feet above the surrounding forest. He then dispatched a confident message to Lord Cornwallis: “I arrived today at Kings Mountain and have taken a post where I do not think I can be forced by a stronger enemy than that against us.”

Colonel William Campbell, elected to lead the rebels until a general officer appeared, learned of Ferguson’s position and decided to pursue and assault at once. He reasoned that the mountain men, always in fear of Indian uprisings, would not remain east of the mountains for long. Also, if Ferguson retreated farther he would be in such proximity to Cornwallis as to preclude attack.

Campbell thus moved forward to the “Cowpens,” a popular camping site, and decided to streamline his now-numerous force. An inspection culled out those without horses or proper arms, and those too sick to continue. A strike force of about nine hundred men would move out to deal with the British column.

Marching at night in a pelting rain, black felt hats pulled low and gunlocks protected by wrappings of bags or blankets, the advance began. Sixteen-year-old James Collins recalled the gnawing hunger as he and his comrades lived on raw turnips, parched corn, and a few spoonfuls of honey. Shortly after 1 pm the column approached Kings Mountain, dismounted, and smoothly filed left and right, silently surrounding the well-identified British position.

Atop the field at the Battle of Kings Mountain, Ferguson’s men awakened to increasing rain, and huddled about their campfires or under tent flaps. In mid-afternoon, Captain Alexander Chesney checked his pickets, located in the woods at the foot of Kings Mountain, and had just returned to the campsite when shots rang out. By 3 pm the “zip” of rifle balls and the eerie, shrill, cry of the fox hunter told Chesney that the enemy was approaching in large numbers.

Chesney recalled that one moment all was peaceful and quiet, and the next the Rebel war whoop arose from all quarters. Chesney scattered his Loyalist militia, natty pine sprigs in their hats, in a straight line up the mountain’s crest searching for the patriot battle line. Ferguson marshaled the red-coated Provincial regulars into a mobile reserve as the volume of rifle fire swelled, although as yet few of the enemy could be seen. The mountainside was covered with heavy woods, innately utilized by the mountaineers, while the mountain crest was open, cleared land. These fringe-coated backwoodsmen needed no instruction in tactics, simply finding good cover and getting close enough for the deadly long rifles to speak.

The contrast in weaponry would prove most decisive on this overcast afternoon, even more so as the tactics employed by each commander worked to the advantage of the Rebels. Most of Ferguson’s troops were armed with the tough, dependable Brown Bess musket. This .75-caliber smooth-bore had an accurate range of under one hundred yards. With tremendous stopping power, the impact of its large bullet could knock a soldier from his feet. Head or belly wounds from such a weapon usually meant death, while an arm or leg shot resulted in amputation.

Rifle vs. Rifle

The Americans were all armed with the Dickert or Pennsylvania rifles, civilian hunting weapons of fragile construction but amazing accuracy. With seven or eight rifling grooves, its .54-caliber ball could find its mark at three hundred yards, particularly when in the hands of these experts. Slow and precise to load, the long rifle carried no bayonet and could actually be a detriment in an open-field, stand-up fight. It is interesting to consider just how the ensuing battle would have developed if Ferguson’s men had been armed with his rifle.

In any event, as the swell of battle grew, Patrick Ferguson was everywhere, spurring his mount from crisis to crisis. Blowing his silver whistle, he led the redcoats in volley and charge actions whenever the attackers seemed too near. Each charge drove the Americans pell-mell down the hillside, but when the Loyalists halted and began to rescale the slopes, the “ping” of rifle balls sang about them. One assault almost routed a portion of Sevier and Campbell’s men but the attackers halted on Ferguson’s whistle, blown because Shelby’s men were attacking the Tory militia from the opposite side of the mountain.

This fluid, skirmish-style fighting was natural to the frontiersmen. Three times Ferguson and his redcoats cleared a slope, charging downhill but finding few foes for their bayonets, and each time they suffered heavy losses struggling back uphill. Most of the Rebel casualties occurred in this initial portion of the one-hour battle. But on each occasion the red-haired, blue-eyed Campbell led his Virginians back into the fight, Argyle Claymore held aloft.

But vain was pluck, and vain each charge

for from each tree there came

a deadly rifle bullet

and a little spurt of flame

The men who fired we could not see

they picked us off like game.

(Anonymous Tory Survivor)

Suddenly the Tory militia broke from the narrow end or “heel” of the footprint-shaped mountain as Shelby’s, Sevier’s, and Campbell’s men met on the crest and began to drive the Loyalists back into their camps. Ferguson, Spanish sword in left hand astride his white horse, vainly attempted to rally the fleeing men. His redcoats had been decimated in their charges and his Loyalist militia now cowered about the wagons refusing to return fire. Deciding to break out, Ferguson gathered a group of four or five horsemen and prepared to lead a desperate flight for Charlotte.

As he stood in his stirrups to order a charge, raising his broken sword, a rifle ball struck squarely into his chest, tumbling Ferguson from his horse. One leg caught in a stirrup and his frightened horse bolted. The dapper British commander was dragged parallel to the patriot line and scores of rifle barrels were leveled. Ferguson was struck as many as 17 times, seven balls lodging in his body.

Captain Abraham de Peyster, who assumed command because Chesney had been wounded, quickly realized he had no choice but to surrender. It wouldn’t be simple, however. A flag of truce was raised, but many of the Americans scattered about the mountaintop could not see it. Scores of other Rebels, sworn to gain revenge for earlier Loyalist outrages, shouted “Tarleton’s Quarter” and continued to load and fire. Dangerously exposed, Colonels Campbell and Shelby spurred between the combatants, begging for a cease-fire. The red-headed Campbell, soaking wet with perspiration, ordered the surrendering Tories to sit down.

Finally the guns grew silent only to be shattered by a single shot that toppled American Colonel Williams from his horse. A virtual hailstorm of rifle shots replied and scores of Loyalists fell victim to the renewal of firing. Williams had enemies in both camps, but friend or foe, whoever slew him almost precipitated a massacre.

When the American officers again halted action, the tremendous cost of British resistance to American riflemen was tabulated. One hundred fifty-seven Loyalists were killed outright, 163 seriously wounded, of which many would succumb, and 698 captured. Not a single Loyalist escaped from the Battle of Kings Mountain. Warfare, particularly in the South, was by this date really civil war, pitting neighbor against neighbor in cruel and merciless combat. Little compassion would be displayed by the victor or, in truth, expected.

The patriots buried the dead poorly in long trenches, covered with leaves, bark, branches, and dirt. The Loyalist wounded were left to their own resources. Both captors and captives slept on the field, suffering from lack of rations.

Brave, handsome Patrick Ferguson, his body stripped and abused, was wrapped in a cowhide alongside Virginia Sal, who had been slain early in the fight, and buried near where he fell. Artifacts of his possession, such as his Spanish sword, whistle, rifle, watch, and ring, became treasured household prizes of Tennessee mountain families, a hundred years hence.

At dawn the Americans were up and on the march. Campbell and his officers feared pursuit by Tarleton’s cavalry. Additionally they had expected to capture Ferguson’s supply train and when his wagons were found to be empty the food situation was critical. The long double column of horsemen, herding prisoners on foot, moved 16 miles the first day despite flooded countryside. The prisoners carried captured arms and equipment, complaining of their hunger. On October 13 the column reached Bickerstaffs where supplies were waiting and pursuit appeared unlikely.

The mountaineers, recalling Loyalist hanging of Rebels after the battle at Camden, demanded that offenders and turncoats among the prisoners stand trial. The most flagrant Loyalists were brought to a court martial, and on October 14 a board of 12 field officers began hearings. A large number of prisoners was called before the board and 36 sentenced to hang. At 6 pm the hangings began on the gallows tree near Bickerstaffs. Colonel Mills, Captains Chitwood and Wilson, and six privates were hanged before the American officers put a halt to these unfortunate events.

The astounding American victory at the Battle of Kings Mountain was complete and conclusive, unlike most actions in this long war of attrition. The encounter was so unexpected it appeared almost accidental: a fight initiated by the sudden appearance of an American force that weeks before did not exist, and weeks hence would as abruptly dissolve.

The sudden defeat sent a shockwave through British aspirations far beyond the real importance and size of the affair; one from which British commanders were never able to recover. American spirits, at a nadir, were rejuvenated. Strangely, the battle was contested entirely by Americans, either Loyalists or patriots. So many of the participants were of Scot descent that it resembled a grudge fight between two clans. In addition, both commanders, Patrick Ferguson and William Campbell, were Scots.

This minuscule setback with gigantic implications can primarily be accredited to the miscalculations of one of the best officers on the field, Lt. Col. Patrick Ferguson. He unwisely precipitated the campaign by an imperious challenge to a grossly misunderstood foe. When deserters brought him information on the size of the American force, he selected disadvantageous ground and used tactics reminiscent of British General George Braddock in an earlier ill-fated encounter in the backwoods.

Ferguson knew well the deadly nature of the long rifle and advocated them for his own army. But he attempted to recast his American Loyalists as disciplined British regulars and insisted that cold steel would quickly disperse the American riflemen.

Lighthorse Harry Lee, when observing the position on the Battle of Kings Mountain years later, summed up the decision to fight there by saying, “This spot was more assailable by the rifle than it was defensible by bayonet.”

Alexander Chesney blamed the humiliating defeat on rocky terrain and heavy woods that favored guerrilla tactics, and the rifles of the enemy over volleys and bayonet charges. But the inordinate pride and stubborn arrogance of Patrick Ferguson, who never allowed himself to understand the men he fought, permitted the Rebels’ advantages to be maximized in an unequal contest. Through his tactical errors and some plain poor fortune, humiliating defeat and death on a wilderness peak befell this honorable soldier of the King.

’Twas on a pleasant mountain

the tory heathen lay.

With a doughty Major at their head

one Ferguson, they say

Cornwallis had detached him

a thieving for to go

And catch the Carolina men

or lay the rebels low.

(Unknown Rebel Poet)

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments