By Cowan Brew

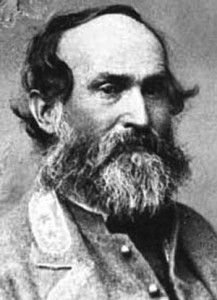

The unrelentingly harsh winter of 1864-1865 gave no respite to Virginia’s war-torn Shenandoah Valley. Heavy snows and frigid temperatures made travel difficult, and the two opposing armies found themselves literally frozen into place, 90 miles apart and in no particular hurry to get at each other again before the weather broke. At the northern end of the valley, in Winchester, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s Union Army of the Shenandoah waited in comparative comfort, warm, dry, and well supplied by the increasingly efficient Quartermaster Corps. But their Confederate counterparts at Staunton were not so fortunate. There, Lt. Gen. Jubal “Old Jube” Early’s Army of the Valley huddled together miserably, wet, hungry, and shivering in rundown huts and ragged tents. The men’s morale was as low as the temperature outside. “Men’s spirits dull, gloomy, and all are evidently hopeless,” wrote one private, “waiting for we know not what end.”

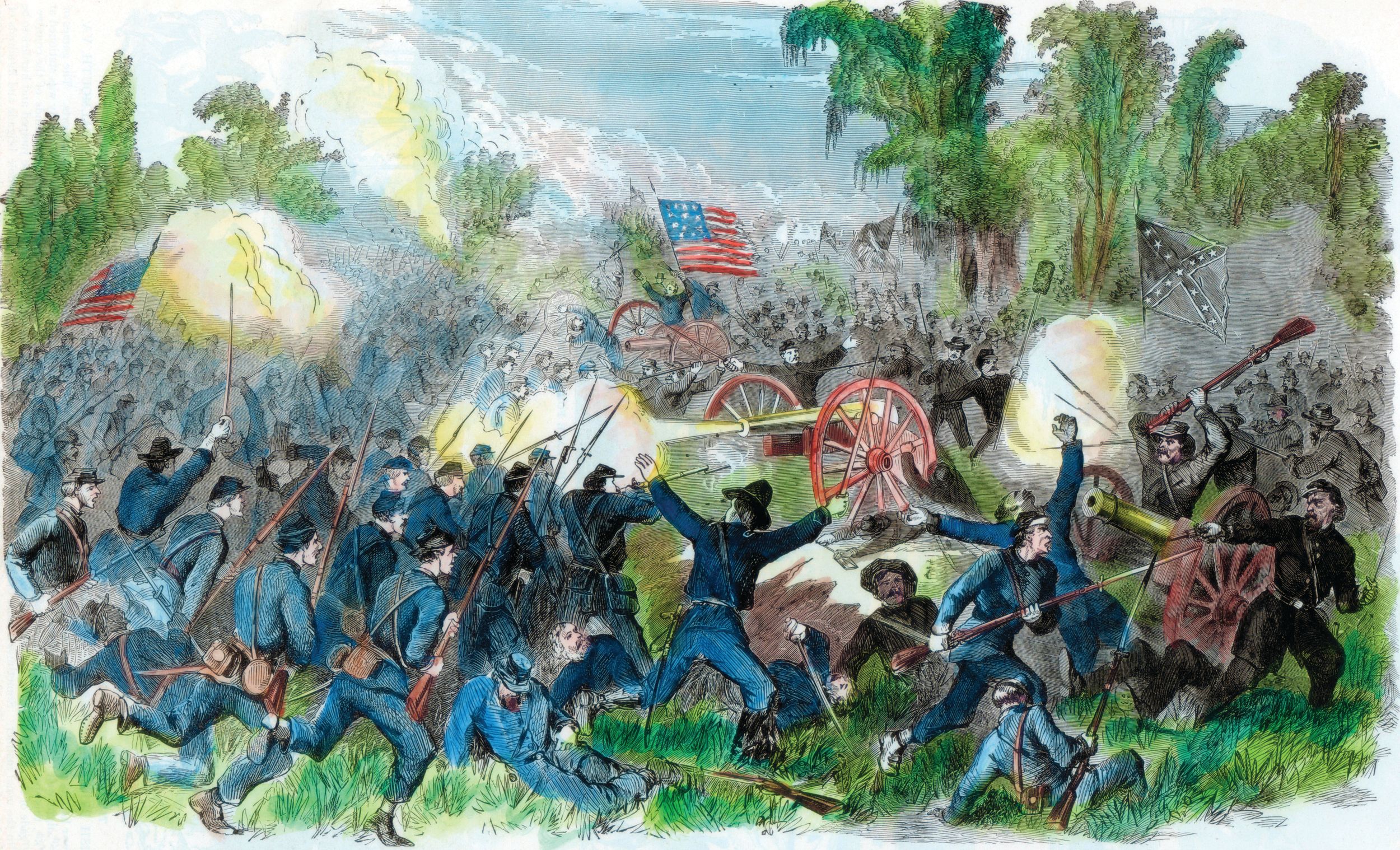

The two armies’ contrasting moods reflected their recent history with each other. Three times in the past six months—at Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, and Cedar Creek—Sheridan’s Union forces had decisively beaten Early’s men. The third loss, at Cedar Creek, had been the most demoralizing for the Confederates, who for much of the day on October 19 had believed, with good reason, that they had finally bested their hated foes. That morning, before dawn, while the diminutive Union commander was still asleep in Winchester after a whirlwind visit to Washington, Early’s men had waded across icy, chest-deep water in the Shenandoah River and fallen on Sheridan’s unsuspecting camp at Cedar Creek. The surprise attack, spearheaded by three divisions under Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon of Georgia, had come within an inch of destroying Sheridan’s entire army, which fell back in disarray to a new position eight miles north at Belle Grove.

“Glory Enough For One Day”

Gordon, an experienced commander, had wanted to press forward immediately, but a prematurely jubilant Early shrugged off Gordon’s suggestions. “This is glory enough for one day,” Early said with airy satisfaction. But while Early celebrated and his hungry men happily looted the abandoned tents of their Union counterparts, Sheridan hurried back to his army, alerted by reports of heavy artillery firing in the vicinity of Cedar Creek. Accompanied by 20 troopers and a handful of staff officers, Sheridan completed a stirring 10-mile gallop to the battlefield, a dash that immediately became famous as “Sheridan’s Ride.” Once on the field, the Union commander rearranged his lines and inspired his troops with some Gaelic-inflected profanity: “Give ‘em hell, God damn em! Face the other way! We’ll lick those fellows out of their boots!” A spirited infantry counterattack ably supported by cavalry completely reversed the Confederates’ gains and, as Gordon had feared, turned the apparent victory into another demoralizing defeat. Union Maj. Gen. William Emory, watching the wild celebration with his aides, predicted of Sheridan, “This young man, only about thirty years old, has made a great name for himself today.”

Gordon, an experienced commander, had wanted to press forward immediately, but a prematurely jubilant Early shrugged off Gordon’s suggestions. “This is glory enough for one day,” Early said with airy satisfaction. But while Early celebrated and his hungry men happily looted the abandoned tents of their Union counterparts, Sheridan hurried back to his army, alerted by reports of heavy artillery firing in the vicinity of Cedar Creek. Accompanied by 20 troopers and a handful of staff officers, Sheridan completed a stirring 10-mile gallop to the battlefield, a dash that immediately became famous as “Sheridan’s Ride.” Once on the field, the Union commander rearranged his lines and inspired his troops with some Gaelic-inflected profanity: “Give ‘em hell, God damn em! Face the other way! We’ll lick those fellows out of their boots!” A spirited infantry counterattack ably supported by cavalry completely reversed the Confederates’ gains and, as Gordon had feared, turned the apparent victory into another demoralizing defeat. Union Maj. Gen. William Emory, watching the wild celebration with his aides, predicted of Sheridan, “This young man, only about thirty years old, has made a great name for himself today.”

So he had. Sheridan’s improbable victory at Cedar Creek, quickly immortalized in poet Thomas Buchanan Read’s 63-line ballad, “Sheridan’s Ride,” took the North by storm and made good on Emory’s prediction. Coupled with Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s capture of Atlanta earlier that fall, the Union victory at Cedar Creek went a long way toward enabling President Abraham Lincoln to win reelection over Democratic nominee (and former Union commander) George B. McClellan. Lincoln’s victory at the ballot box would ensure that the North would continue pressing its “hard war” against the South. Nowhere was that concept to be more harshly carried out than in the Shenandoah Valley.

Sheridan Goes After the Shenandoah Valley

While the two armies waited out the winter weather, the Union Army’s commanding general, Ulysses S. Grant, urged Sheridan—who needed little convincing—to devastate the Shenandoah Valley. Under orders from Sheridan to “consume and destroy all forage and subsistence, burn all barns and mills and drive off all stock in the region,” Union troopers commenced what became known as “the Burning Raid,” inflicting more than a million dollars’ worth of damage on hard-pressed Southern farmers in a mere four days. Barns, stables, corncribs, and smokehouses were set ablaze; cattle, sheep, hogs and horses were carried off or consumed. “Should complaints come in from the citizens of Loudoun County,” Sheridan advised Brig. Gen. John D. Stevenson, “tell them that they have furnished too many meals to guerrillas to expect much sympathy.” Sheridan, as usual, had little sympathy to spare.

[text_ad]

Not all his men were so unsympathetic. Private Charles Humphreys of the reserve brigade observed the destruction at close hand. “In one day,” he noted, “two regiments of our brigade burned more than 150 barns, 100 stacks of hay and 6 flour mills, besides having driven off 50 horses and 300 head of cattle. This was the most unpleasant task we were ever compelled to undertake. It was heart piercing to hear the shrieks of women and children, and to see even men crying and beating their breasts, supplicating for mercy on bended knees, begging that at least one cow—an only support—might be left. But no mercy was allowed. Orders must be obeyed.”

Most of Sheridan’s subordinates were less moved by civilian suffering. One in particular, brevet Maj. Gen. George Armstrong Custer, was only too happy to accommodate Sheridan’s wishes. Repeatedly that fall Custer’s 3rd Cavalry Division had crossed swords with Lt. Col. John Singleton Mosby’s redoubtable 43rd Virginia Cavalry Battalion. Although Mosby’s men were legally sworn Confederate soldiers, their irregular raiding habits had caused Custer and his troopers to treat them as guerrillas. In early October, near Dayton, Custer had summarily executed a Southern bushwhacker, and a few days later one of Mosby’s troopers was hanged from a tree alongside the road, wearing a placard that read, “In retaliation.” And after a favorite trooper in the 6th Michigan was killed by a sniper shot from one of two adjacent houses, Custer’s men dragged the owners of both houses outside and shot them, without bothering to determine which—if either—was the guilty party.

Custer Heads for Washington

As the easily recognizable Union general in the valley, the flamboyant Custer was blamed for killings he did not commit. After Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt executed six of Mosby’s Rangers at Front Royal on September 23, four by shooting and two by hanging, residents of the town erroneously identified Custer as the perpetrator. Custer had been present at the scene behind the local Methodist Church, although not in command, but that was enough for Mosby to begin stockpiling for retribution any Custer troopers he managed to capture. On November 6, at Rectorsville, he made 27 Union prisoners draw numbered slips of paper to determine which seven would be executed in reprisal for the executions at Front Royal and elsewhere. The unlucky seven were led away to be hanged—two managed somehow to escape—and a note was left dangling from one of the bodies: “These men have been hung in retaliation for an Equal number of Colonel Mosby’s men hung by order of General Custer, at Front Royal. Measure for measure.”

Mosby’s reprisals put an end to the blatant violations of the military code by both sides, but they left Custer and his men understandably bitter. That bitterness was compounded in mid-December when Brig. Gen. Thomas Rosser’s Confederate cavalry raided Custer’s camp at Lacey Springs, nine miles north of Harrisonburg. Little damage was done to the camp, but an embarrassed Custer was forced to explain to Sheridan how he had managed to get himself attacked while supposedly on a raid himself. Adding to Custer’s embarrassment was the fact that Rosser had been his best friend at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Fortunately for Custer, Sheridan chose to overlook the minor incident and instead selected his protégé to lead an honor guard to Washington to present captured Confederate battle flags to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. The hard-to-please Stanton was charmed by Custer and his beautiful young wife, Libbie, praising Custer as “a gallant officer.” The Custers spent the rest of the winter living with a family of Quakers named Glass four miles outside Winchester.

In January 1865, the Custers took a 20-day furlough to their hometown of Monroe, Michigan. A fellow traveler on the train to Michigan jotted down a hasty, rather hero-worshipping account of the general in his dairy. “Genl Custar [sic] reminded me of Tennyson’s description of King Arthur,” wrote Lewis T. Ives. “He is tall straight with light complexion, clear blue eyes, golden hair which hangs in curls on his shoulders [and] has a fine nose.” Custer couldn’t have said it better himself. He even found time to make his peace with God, experiencing a religious conversion at a Sunday evening service at the Monroe Presbyterian Church, an experience that left him feeling, said Custer, “somewhat like the pilot of a vessel who has been steering his ship upon familiar and safe waters but has been called upon to make a voyage fraught with danger. Having in safety and with success completed one voyage, he is imbued with confidence and renewed courage, and the second voyage is robbed of half its terror. So it is with me.”

10,000 Cavalry At Four Abreast

In mid-February, back in Virginia, Custer found out what his next voyage would be, when he received a new assignment from Sheridan. For the past four months Grant had been urging Sheridan to cut the Virginia Central Railroad at Charlottesville and move eastward toward Richmond to threaten the rear of Robert E. Lee’s lines at Petersburg. Citing bad weather, Mosby’s guerrillas, and the (unlikely) threat of Confederate reinforcements in the valley, Sheridan delayed. Grant, who was even more stubborn than Sheridan, persisted, sending his subordinate a new set of orders. Sheridan was to destroy the railroad and the James River canal, capture Lynchburg, and then either return to Winchester or link up with Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army in North Carolina. Sheridan would obey—but only up to a point.

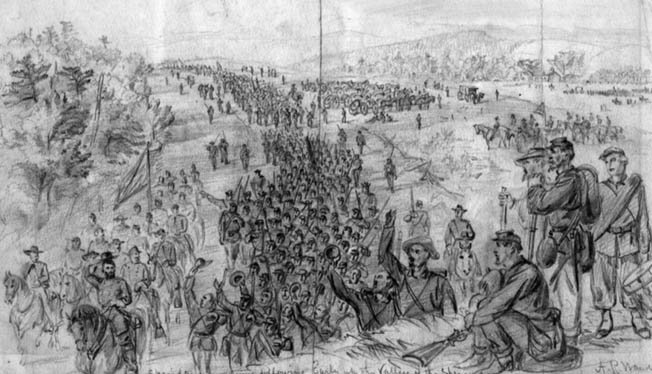

At dawn on February 17, 1865, Sheridan broke camp at Winchester and headed south with two full cavalry divisions, a section of artillery, and a long train of supply wagons, pontoons, ambulances, and medical wagons. Each trooper was issued five days’ rations for himself, 30 pounds of forage for his horses, and 75 rounds of ammunition. Winchester resident Emma Reily watched the invaders leave. “I witnessed one of the grandest spectacles that can ever be imagined as they were leaving,” she wrote. “10,000 cavalry passing our house four abreast thoroughly equipped in every detail. The horses, having been in winter quarters so long, had been fed high and curried and rubbed until their coats shone like satin. Each man had a new saddle, bridle and red blanket, and all their accouterments such as swords, belts, etc., shone like gold. It was a grand sight, requiring hours in passing.”

Back at Staunton, Jubal Early was not so thrilled by the Federals’ departure. Knowing Sheridan only too well by this time, the Confederate commander assumed rightly that the enemy movement presaged new fighting. Spies in Winchester and soldiers manning observation posts on nearby Massanutten Mountain had already detected signs of the impending Union advance. Confederate Private Henry Berkeley summed up his commanding general’s fears in his diary. “We hear that the Yanks are collecting a very large cavalry force at Winchester and are expected to move up the Valley as soon as the weather permits,” Berkeley wrote. “I don’t see how it is possible for our little force to make any headway against them. We are only 1,500; they are reported to be 15,000. They will run over us [by] sheer weight of numbers. Who will be left to tell the tale?”

As it was, Berkeley overestimated the Federals’ strength by a third, but his fears were shared by Early. All winter the general had brooded over his three defeats, particularly the lost opportunity at Cedar Creek. Ungenerously, Early blamed his own failure on his men, complaining to Robert E. Lee, “We had within our grasp a glorious victory, and lost it by the uncontrollable propensity of our men for plunder.” Ignoring his own delay, even after Gordon’s urging, to follow up the initial attack, Early blamed his own subsequent retreat on “panic created by an insane dread of being flanked and a terror of the enemy’s cavalry.” That terror—or at least apprehension—was well earned. Twice before, the Confederates had been outflanked, at Winchester and Fisher’s Hill, and their own cavalry had been sent reeling at Tom’s Brook. The common Confederate foot soldier had good reason to fear the blue-coated Union horsemen, who had no similar fear of their Rebel counterparts.

Early Was On His Own

Lee, who had slowly and steadily stripped Early of most of his command to reinforce his own works at Petersburg, somewhat unhelpfully advised Early “to produce the impression that the force was much larger than it really was.” He should do the best he could. Early did, indeed, do his best, ordering Rosser to recall his horsemen, who had temporarily disbanded to spend the winter in their homes, and delay the Union advance at Mount Crawford, where a covered bridge crossed the North River. In the meantime, Early directed Maj. Gen. Lunsford Lomax at Millboro, 40 miles west of Staunton, to bring his understrength cavalry division east. He sent additional orders to Brig. Gen. John Echols to rush his infantry brigade by rail to Lynchburg, which Early assumed was Sheridan’s ultimate target. Early had all military stores removed from the city to prevent them from falling into Union hands in the likely event of another Confederate defeat.

While Early was telegraphing a flurry of hasty orders, Sheridan’s blue column proceeded in its usual swift but orderly fashion up the macadamized Valley Pike to Woodstock, where it camped for the night of February 27. The next morning the march resumed with Custer’s 3rd Division on point. Despite a steady rain, Union spirits were high, and Sheridan bragged to Grant,“The cavalry officers say the cavalry was never in such good condition.” The mood darkened noticeably when eight troopers drowned while attempting to swim their horses across the rain-swollen North Fork of the Shenandoah River. “Many others would have drowned had it not been for the superhuman efforts of a number of officers and men who rushed into the stream and at great personal risk brought them to shore,” reported Colonel Alexander Pennington, commander of Custer’s 1st Brigade. The rest of the army, having learned a hard lesson, waited for Union engineers to throw a preconstructed pontoon bridge across the river.

Sheridan Goes “In At The Death”

At officers’ call the next morning, Sheridan informed his subordinates “that we were on a big march of not less than 350 or 400 miles.” He left their ultimate destination undisclosed, if indeed he knew it himself, but he made it clear that he had no intention of returning to Winchester after the raid. Nor, for that matter, did he intend to reinforce Sherman in North Carolina, “wherever he may be found.” Like many if not most of the soldiers in both armies, Sheridan sensed that the war was drawing to an end in Virginia, and he intended, as he put it, to be “in at the death.” Custer’s division again took the lead.

At Mount Crawford the Union column ran into Rosser, who had somehow managed to scrape together a couple hundred cavalrymen and was attempting to set fire to the covered bridge across the North River. Custer ordered newly arrived Colonel Henry Capehart to take Capehart’s 3rd Brigade and secure the bridge at all costs. Capehart, who had just transferred into Custer’s 3rd Division from the 2nd, immediately ordered two regiments to swim across the river above the bridge while he personally led to the rest of the brigade across the now burning timbers. The Confederates managed one last volley before melting back into the woods, although not before 37 of their men had been taken prisoner. The bridge was saved.

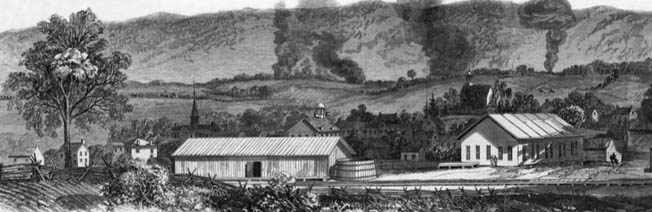

Sheridan’s column bedded down for the night at Cline’s Mill, seven miles north of Staunton. The general directed Colonel Peter Stagg to take his Michigan brigade around Staunton and burn the railroad bridge to the east at Christian Creek to prevent the Rebels from evacuating the town in the dark. Stagg’s men piled fence rails on top of the span and burned it to the waterline, but they were too late to stop the enemy evacuation. Early and his staff had already ridden out of Staunton at 3:45 that afternoon to link up with Brig. Gen. Gabriel C. Wharton’s ragtag infantry division at Waynesboro, a small village located midway between Staunton and Charlottesville on the banks of the South River near Rockfish Gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains. It was a narrow escape.

Sheridan & Early Look Toward Waynesboro

The next morning Sheridan entered Staunton like a conqueror. The streets were deserted and the warehouses empty, but somehow Early had left Sheridan a message to meet him in battle at Waynesboro—or so Sheridan claimed, anyway. It was unlikely that Early, outnumbered 8-to-1 and leaving town in a dust-swirling haste, would have had either the time or the temerity to challenge his pursuer to a duel to the death. More likely, Early expected Sheridan to continue south to Lynchburg, where Early had already stockpiled his largest remaining infantry force. Whatever the truth of the matter, Sheridan explained later that he was reluctant to leave Early’s force—all 1,200 of them—operating openly in his rear, although it was anyone’s guess what possible harm they could have done in their present state. Still, if Early wanted to fight at Waynesboro, Sheridan was more than happy to accommodate him. Each step Sheridan took to the east carried him that much closer to Grant and that much farther away from Sherman, which was his main purpose for continuing his pursuit of Early. All in all, it seemed a fair trade to Sheridan.

Sheridan directed Custer to “ascertain something definite in regard to the position, movements, and strength of the enemy, and, if possible, destroy the railroad bridge over the South River at that point.” Since Sheridan already knew how many men Early had and where they had gone, the order did not make much military sense, but Custer as always obeyed with all due speed. He mounted up and headed east.

Early had uncharacteristically gotten the jump on Sheridan, having already reached Waynesboro and set about preparing a makeshift defensive line on a low ridge just west of town. Wharton, a blooded veteran of all Early’s battles in the Shenandoah Valley, was given the unenviable task of holding on to a three-quarter-mile-long line of rifle pits with a skeleton force of 1,000 infantry, 100 cavalry, and six artillery pieces. The line was stretched thin, a mere 200 yards from the rain-swollen South River, and Wharton’s sleet-soaked veterans were uncomfortably aware that they had a raging waterway in their rear. To make matters worse for the defenders, the line did not stretch far enough south to touch the westward bend of the river, leaving an eighth of a mile gap and exposing the Confederate flank.

A Critical Confederate Error?

Early’s New York-born topographical engineer, Captain Jedediah Hotchkiss, charged later that the general had committed “an unpardonable error” by placing his men in such an exposed position. Early explained, somewhat weakly, that he had placed the men there “to secure the removal of five pieces of artillery for which there were no horses, and some stores still in Waynesboro, as well as to present a bold front to the enemy, and ascertain the object of his movement, which I could do very well if I took refuge at once in the mountain. I did not intend making my final stand on this ground, yet I was satisfied that if my men would fight, which I had no reason to doubt, I could hold the enemy in check until night, and then cross the river and take position in Rockfish Gap.” Early was gambling on being able to outbluff the enemy, and the ever aggressive Custer, for one, was impossible to bluff. He simply charged ahead at all times, regardless of the odds. And this time, as everyone knew, the odds were in his favor.

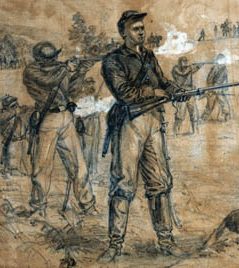

Arriving at Waynesboro at 2 pm on March 2, Custer immediately dispatched Colonel William Wells’ 2nd Brigade to probe the Confederate line. A brisk rattle of fire erupted from the rifle pits, convincing Custer that a headlong frontal assault “would involve a large loss of life.” Ordinarily this didn’t unduly trouble Custer, but he looked around for another approach and soon discovered the dangerous gap between the enemy left and the river. While Wells kept the Confederates occupied on their front, Custer sent Lt. Col. Edward Whitaker, his chief of staff, to order Pennington to dismount three of his regiments and attack the enemy flank through a stand of woods that would obscure their approach.

Everything Lost And All At Once

Wells obeyed briskly and dismounted the 2nd Ohio, 2nd New Jersey, and 1st Connecticut Regiments, all of which were armed with seven-shot Spencer repeating rifles. The brigade’s fourth regiment, the 2nd New York, was held in reserve. At a signal from aptly named bugler Joseph Fought, the Union force began the assault. It did not last long. While Lieutenant C.A. Woodruff’s horse artillery blasted away at the Rebel breastworks, Pennington’s men charged forward at the dead run, yelling like fiends. Meanwhile, Capehart’s 3rd Brigade stormed into the works from the front. The overwhelmed defenders broke for the rear, in what a disgusted Jedediah Hotchkiss termed “one of the most terrible panics and stampedes I have ever seen. There was perfect rout along the road up the mountain.”

Wells obeyed briskly and dismounted the 2nd Ohio, 2nd New Jersey, and 1st Connecticut Regiments, all of which were armed with seven-shot Spencer repeating rifles. The brigade’s fourth regiment, the 2nd New York, was held in reserve. At a signal from aptly named bugler Joseph Fought, the Union force began the assault. It did not last long. While Lieutenant C.A. Woodruff’s horse artillery blasted away at the Rebel breastworks, Pennington’s men charged forward at the dead run, yelling like fiends. Meanwhile, Capehart’s 3rd Brigade stormed into the works from the front. The overwhelmed defenders broke for the rear, in what a disgusted Jedediah Hotchkiss termed “one of the most terrible panics and stampedes I have ever seen. There was perfect rout along the road up the mountain.”

Early, watching the enemy attack from a hill between the rifles pits and the river, saw at once that everything was lost. Cutting through a nearby stand of trees, he and his staff raced on horseback for the bridge leading to Rockfish Gap. Early and Wharton made it, but Dr. Hunter McGuire, the army’s gifted medical director who had treated the mortally wounded Stonewall Jackson two years earlier, was not so lucky. Attempting to jump his horse over a fence rail, McGuire and his mount went sprawling face first into the mud. When he looked up, the first thing he saw was a Union cavalryman pointing a carbine at his head, his trigger finger twitching. Thinking quickly, McGuire made the arcane distress signal used by members of the Masonic Order. Fortunately for him, a Federal officer and fellow Mason rode up at that point and took charge of the shaken Confederate physician, telling the trooper, “This man is my prisoner. Let him alone.”

Tables Turned, Odds Reversed

McGuire was only one of more than 1,200 Confederates captured at Waynesboro, along with all 11 artillery pieces, 17 battle flags, and 150 wagons, including Early’s own headquarters wagon. Union losses were a miniscule nine killed or wounded. After a brief unsuccessful pursuit of Rebel stragglers who made it safely through Rockfish Gap, Custer broke off the attack and rode up to report the victory to Sheridan, who had just arrived on the scene. As Sheridan staff member Captain George B. Sanford remembered, “Up came Custer himself with his following, and in the hands of his orderlies, one to each, were the seventeen battle flags streaming in the wind. It was great spectacle and the sort of thing which Custer thoroughly enjoyed.”

So too did Sheridan, who praised Custer for making a “brilliant fight” and reported to Washington with pardonable pride that the battle at Waynesboro had closed hostilities in the Shenandoah Valley. It also closed Early’s military career. Never again would Old Jube command troops in battle. While Sheridan went on to complete a brilliant Civil War career and personally attended Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Ulysses S. Grant in Wilmer McLean’s parlor at Appomattox, Early spent the last weeks of the war licking his wounds and preparing to retire to an embittered postwar career as one of the most unreconstructed of Southerners. He neither forgot nor forgave.

As for Early’s longtime opponent, the postwar years eventually brought Sheridan the command of the entire United States Army, one of whose members, golden-haired George Armstrong Custer, would meet his fate in typical Custer fashion on the banks of the Little Bighorn River in Montana 11 years later. There, unlike the Confederates at Waynesboro, the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors enjoyed a vast numerical advantage over Custer’s 7th Cavalry. The tables had been turned, the odds reversed, and Custer lost his last desperate wager, almost without placing a bet.

& will give “Old Jube” a bit of credit, earned a promotion @ the First Battle Of Bull Run, but was wounded @ Battle of Williamsburg & took part in the 2nd Battle of Bull Run. During the battle of Antietam he commanded his troops @ the battlefield’s West Woods. During the Battle of Fredericksburg reinforcing the right wing of the

Confederate army driving off a heavy Federal assault, & led the final assault @ Chancellorsville driving off the Yanks under John Sedgwick @ Salem Church. And not too mention first day @ Gettysburg he routed the Union’s 11th Corps north of the town. After The Wilderness & Spottsylvania transferred to Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley where he organized a daring operations of the war & routing the Union forces & Lynchburg

Once again, Early prematurely stopped his first day advance in Gettysburg and didn’t secure high ground, which was within reach given condition of Union forces at battle’s start. Union forces moved into position overnight and fully capitalized on this advantage. This error had a significant impact to outcome of the Gettysburg campaign.

This is a well written piece. Thank you

My GGF was a cavalryman with the First NJ AKA The ‘Butterfly Boys’ because of their uniforms. He was wounded during the Petersburg campaign but remained through Appomattox.

Eventually his wound would debilitate him and he spent his remaining years in an old soldiers home in NJ.

Excellent writing, excellent history. This is great piece, Mr. Brew!