by William E. Welsh

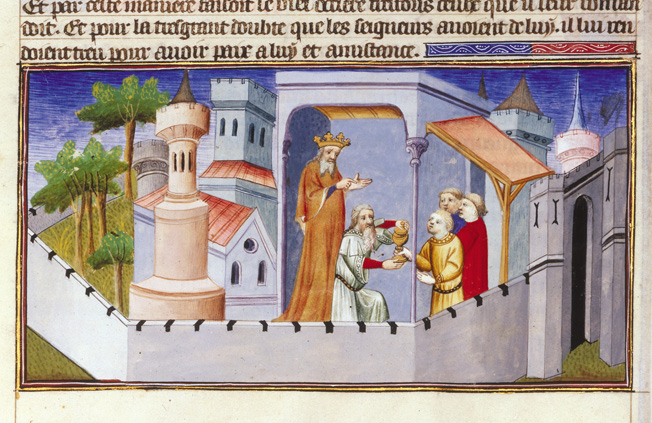

King Richard I of England, known as “The Lionheart,” was imprisoned in spring 1193 in Germany on his return from the Third Crusade by Duke Leopold V of Austria for alleged crimes and insults that occurred when they were participating together in the crusade. Richard’s mother paid his ransom.

[text_ad]

Upon returning to France, where he had vast holdings in modern France by virtue of the Angevin inheritance, Richard found that his nemesis, King Philip II of France had seized the castles in the Vexin region of eastern Normandy. On May 10, 1194, Richard arrived in France determined to retake the Vexin. For the next five years, the two monarchs fought tenaciously over the matter.

Philip Plainly ‘Outgeneraled’ by the Lionheart

At nearly every turn, Philip was outgeneraled by Richard. One well-documented clash between the two occurred at the Battle of Gisors fought September 27, 1198. Moving in two columns, Richard’s army captured three castles on the eastern border of the Vexin in one day. This put Philip, who was near Gisors Castle, in danger of being cut off.

With 300 knights, as well as mounted sergeants and foot soldiers, Philip marched on Courcelles Castle to reinforce its garrison. But Philip was unaware it was already in English hands. Effective patrols by the English (Richard himself rode on these patrols), located the French. Richard issued orders for his columns to converge, and they rapidly pursued the French, who remained unaware of the enemy’s location.

The French, unprepared for battle, changed course and rode hard for the safety of Gisors castle, which lay closer than Courcelles Castle. As they neared Gisors, Richard’s host attacked. Richard himself killed or injured three French knights with a single lance (without it breaking and having to be replaced). The battle was a resounding English victory.

So many French soldiers, many of them mounted, crowded the bridge leading into Gisors that it collapsed beneath them. Philip was among those who plunged unexpectedly into the water in armor. Twenty French knights drowned, but Philip was pulled to safety. “The king of France fell into the river Ethe, and [had] to drink of it, and, if he had not been speedily dragged out, would have been drowned therein,” wrote historian Roger of Hoveden.

Question

How Many French Knights Were Killed, Executed And Drowned In The Battle of Gisors