By Joshua Shepherd

For Union Lieutenant Harrison Millard, it was an unsettling development. An aide on the staff of Brig. Gen. Lovell Rousseau, Millard had ridden out ahead of the lines on the morning of October 8, 1862. His division had formed up earlier that morning for an assault on Confederate troops in Perryville, Kentucky, but it looked now as if there would be no fight. Dust clouds in the distance, he thought, indicated that the Rebels were on the run.

Scouting a farmer’s woodlot in the company of a newspaper correspondent, an incredulous Millard stumbled across a wounded but talkative Confederate. “I asked him what he was doing there,” the lieutenant recalled, “and he replied that he was wounded, and had been left there by his regiment, which only a short time before had gone on.” Millard dashed off to report his discovery to Rousseau but was surprised that his chief simply brushed him off. “Oh bosh,” the general dismissively replied, “it is impossible. There is no one anywhere near here.”

Bragg’s Dilemma

Such hubris had already enabled a major Confederate thrust into the heart of Kentucky. Reeling from the disappointing and bloody reverse at Shiloh during the first week of April, General P.G.T. Beauregard’s Army of the Mississippi fled Tennessee, abandoned its base at Corinth, and retired to Tupelo to lick its wounds. Defeated, demoralized, and ill disciplined, the army was described as being “little more than a mob.” Exasperated by what he considered Beauregard’s timid strategic posturing, President Jefferson Davis opted to replace him with a personal favorite—General Braxton Bragg.

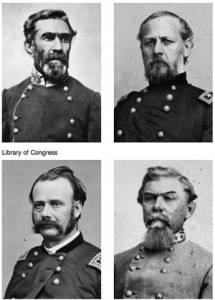

Despite a lack of experience at independent command, Bragg had much to commend him to such a weighty assignment. A stern West Pointer and Mexican War hero, Bragg projected competence. A skilled logistician and fussy organizer, he worked tirelessly to feed and resupply his haggard army, and his initial weeks in command at Tupelo seemed to justify Davis’ decision. But as a leader of men, Bragg soon sowed seeds of ill will that would compromise his ability to command. Despite his organizational skills, Bragg was notoriously forbidding, contentious, and given to castigating his subordinates. His icy personality, paired with a vigorous restoration of discipline, quickly earned him the distrust of his own men.

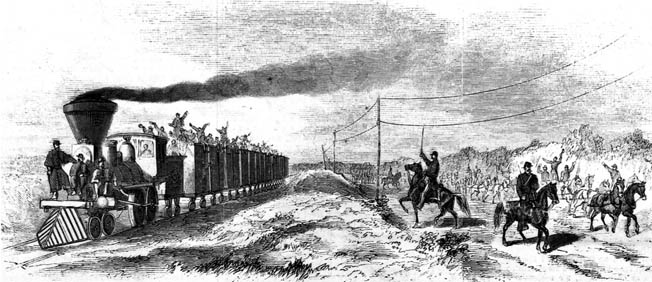

Bragg fretted about how best to employ his 32,000men at Corinth against the Federals, who, with 110,000 troops, handily dwarfed the Confederate Army of the Mississippi. Fortunately for Bragg, his dilemma was partly solved due to the unorthodox decisions of his opposite number. Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, who assumed direct command of Union forces in the theater following the bloodbath at Shiloh, inexplicably decided to split up his forces at Corinth, dispatching troops to relatively static posts throughout Arkansas and Tennessee. The only troops likely to see any serious action were those of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio. Buell was ordered to strike due east along the Memphis & Charleston Railroad on a roughly 230-mile campaign aimed at the vital junction of Chattanooga, Tennessee. Opposed to such a move from the outset, Buell soured further when his advance was stymied by elusive Confederate cavalry that wrecked roads, bridges, and rail lines in his front, flank, and rear.

Edmund Kirby Smith’s Underhanded Scheming

The sudden dispersal of Union manpower removed the immediate threat of a major Federal thrust into Mississippi and afforded Bragg the unexpected opportunity to seize the initiative. Unfortunately for the Confederacy, Bragg remained puzzled by his options, and his subsequent actions took shape somewhat haphazardly. Rather than aggressively implement a coherent strategic vision, Bragg wielded the Army of the Mississippi in passive reaction to the decisions of the enemy, as well as the machinations of a particularly wily fellow officer.

Based near Chattanooga as the commander of the Department of East Tennessee, Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith had been contemplating a startlingly ambitious campaign of his own. Seemingly disenchanted with the job of occupying Unionist East Tennessee, Smith had formulated a grandiose plan to assume the offensive, reclaim Kentucky for the Confederacy, and achieve a measure of fame in the process. With Buell’s army clearly aimed at Chattanooga, Smith issued desperate appeals for reinforcement. Bragg accommodated by dispatching a division under Maj. Gen. John McCown to Smith’s aid. In spite of his hysterical appeals for support, Smith, who kept the lid on his Kentucky plans, tellingly posted a sizable body of men at Knoxville, roughly 120 miles northeast of Chattanooga.

In fact, Chattanooga was under no imminent threat. Buell’s halfhearted advance bogged down near Decatur, Alabama, continually harassed by enemy cavalry raids. Chief among the culprits were Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest and Colonel John Hunt Morgan, two inveterate raiders who were making names for themselves by cutting Federal lines of communication in Tennessee and Kentucky. Worse yet, Buell discovered by the first of August that his path to Chattanooga was barred by a far more formidable force—Bragg’s Army of the Mississippi.

Incessantly pestered by Kirby Smith’s pleas for reinforcement, Bragg made the decision on July 21 to transfer his base of operations to Chattanooga. With the Memphis & Charleston Railroad held by Buell, Bragg plotted an elaborate alternate route through southern Alabama and Georgia before entering Chattanooga through the back door. On July 31, Bragg and Smith met to formulate a plan of action. The two men agreed on a concerted move: after Smith dislodged Federal troops then occupying Cumberland Gap, they would combine forces and strike Buell’s rear in Middle Tennessee.

Bragg failed to take into consideration Kirby Smith’s underhanded scheming. On August 9, Smith dropped something of a bombshell. Federal troops at the Cumberland Gap, he claimed, were far too well supplied to be attacked head on; he suggested a march of 130 miles in the other direction, toward Lexington. Bragg left the door open for such a move, demurring only that the idea might be “unadvisable.” At that, Smith was off and running; by the middle of August he was headed pell-mell for Kentucky. On August 30, Smith scored a lopsided victory at Richmond, and on September 2 his forces occupied Lexington.

The Mad Dash for Kentucky

Pried away from his base in Mississippi and manipulated into assuming the defense of Chattanooga, Bragg now found himself maneuvered into a mad dash for Kentucky. What ensued was a whirlwind 300-mile race. Finally deciding to lunge into the Bluegrass, Bragg made for Glasgow, 95 miles northeast of Nashville and within easy striking distance of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, as well as the Louisville Pike, Buell’s primary artery of supply. Buell, on edge over the threat to his supply lines, set out from Nashville in a desperate attempt to secure the railroad. At breakneck pace, the two armies raced north on converging routes. For his part, Buell was mortified to implement such an embarrassing retrograde but was granted permission by Halleck, who icyily wired back: “March where you please, provided you will find the enemy and fight him.”

The summer of 1862 had been one of the driest on record, and the drought caused wells, creeks, and even small rivers to dry up. Mile after mile during the relentless quest to get ahead of the enemy, the troops tasted little but choking dust clouds kicked up by the passing armies. Officers did what they could to alleviate the shortage, but much of the available water was barely fit for human consumption. “Nothing to drink but pond water,” recalled John Duncan of the 3rd Ohio, “thickened with wiggletails, dead mules and horses.”

Footsore Confederates won the punishing race, securing Glasgow on September 11. While Buell groped about for alternate routes, Bragg’s luck began to run out. After one of his brigades was chewed up in an abortive assault on Federal works at Munfordville, Bragg chose to invest the town with his entire army. He easily bagged the Union garrison but wound up losing three days in the process. Bragg painfully vacillated over his options, at one point deciding to dig in and wait for Buell to attack him, then suggesting an immediate link up with Kirby Smith, and finally contemplating the seizure of Louisville.

Buell’s Military Career On the Line

By September 20, Bragg had decided on a concentration with Smith. As he moved northeast, Bragg abandoned the pike and railroad to the Army of the Ohio. Buell was only too happy to take the road, mercilessly pushing his men toward Louisville. On September 25, the Federals entered the city. Buell set to work immediately reorganizing his exhausted army. With his supply hub at Louisville secure, he began making plans to pursue Bragg and give battle. President Lincoln’s patience, however, had run out. From Tupelo to Louisville, Buell had been outmaneuvered for hundreds of miles. In the process, he had failed to fight a single major action.

On September 29, Buell received stunning notification from Halleck that he had been relieved, to be replaced by his second-in-command, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas. Not wanting to undermine Buell, Thomas demurred. In a telegram to Halleck, Thomas pointed out that plans were already underway to pursue the Rebels and he considered it injudicious to assume command in the midst of an active campaign. His position, Thomas argued, was “very embarrassing.” The matter was dropped. Buell, belatedly realizing that his future military career hinged on the outcome of the current campaign, got the Army of the Ohio on the move.

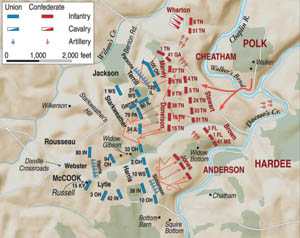

While Buell feinted east toward Frankfort with one division, the bulk of the army angled southeast toward Bardstown. On the left was I Corps, under the command of Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook. A West Pointer and Indian fighter, the personable McCook was held in little esteem by Buell; a less charitable Federal officer called McCook a “chucklehead.” In the center, Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden, a Kentuckian and Mexican War veteran, headed II Corps. He was accompanied by Thomas, who assumed de facto control of the corps. On the right was III Corps, under the command of Charles Champion Gilbert, whose actual rank was somewhat in question. A mere captain just weeks earlier, Gilbert had been advanced to “acting major general” through a bizarre turn of politically motivated events. With fresh stars on his shoulders and a banty rooster attitude about his new rank, Gilbert proved an instant success at rendering himself obnoxious to every man who served under him.

Bragg, who had his army dispersed across Central Kentucky, struggled to discern Buell’s intentions. Federal columns had fanned out from Louisville in all directions, and it was something of a mystery where Buell was leading the bulk of his army. Ultimately convinced that the Federals were targeting the state capital at Frankfort, Bragg settled on a concentration at Versailles, where he optimistically hoped to finally combine commands with Smith, who characteristically dragged his feet over such a move. As his army gave ground to the advancing Federals, Bragg headed for Frankfort to personally assist in arrangements for Kentucky’s new Confederate government. He left direct command of the army to his senior wing commander, Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk, an affable Episcopal bishop turned soldier whom Bragg personally detested.

Little More Than a Demonstration in Perryville?

By October 6, however, Bragg’s other wing commander, Maj. Gen. William J. Hardee, was being pressured by pursuing Federals. Polk, eager to discern Buell’s intentions, directed Hardee to halt, stand his ground, and “force the enemy to reveal his strength.” Hardee reined in his men on imposing hills overlooking the sleepy crossroads hamlet of Perryville, then requested reinforcements to drive off the enemy to his front. Bragg remained convinced that Perryville was threatened by little more than a demonstration, and he ordered Polk to lead another division to Perryville, personally assume command, and whip the Federals who had been harassing Hardee. Once he had all his troops up, Polk would have just shy of 17,000 effectives.

Bragg’s guess was entirely erroneous. Hardee was confronted not with a minor demonstration, but with the entire 55,000-strong Army of the Ohio. Buell, who ironically was convinced that he was up against Bragg’s entire army, began consolidating his troops west of town. To the north, McCook’s I Corps approached on the Mackville Road. In the center, Gilbert’s III Corps was coming up the Springfield Pike. On the right, after a grueling march, Crittenden’s II Corps was expected to move into position on the Lebanon Pike. Buell, who had been injured during a fall from his horse that afternoon, set up headquarters at the Dorsey House on the Springfield Pike and made plans to launch an attack the following morning, as soon as all three corps were in position.

“Tomorrow Morning Early We May Expect a Fight…”

For much of October 7, Buell’s vanguard clashed with Confederate horsemen under the command of Bragg’s cavalry chief, Colonel Joseph Wheeler. Hardee grew increasingly alarmed that he was confronting a good portion of the Army of the Ohio. That afternoon he issued an earnest request to Bragg. “Tomorrow morning early we may expect a fight,” wrote Hardee. “If the enemy does not attack us, you ought to unless pressed in another direction send forward all the reinforcements necessary, take command in person, and wipe him out.” Bragg responded by hurrying Polk. “Give the enemy battle immediately; rout him, and then move to our support at Versailles,” he directed. With a major battle taking shape, the Army of the Mississippi’s commanding general was absent from the field. Buell, aching from his fall, was bedridden at his headquarters. Neither commander was in position to lead his men.

Inevitably, the two thirsty armies converging on Perryville would come to blows over water. When elements of Gilbert’s corps discovered a few stagnant pools in Doctor’s Creek to their front, Buell ordered Gilbert to seize the creek. In the predawn hours of October 8, Colonel Daniel McCook led his inexperienced brigade toward Peter’s Hill, a conspicuous knob thought to be unoccupied that commanded the creek. As McCook’s men mounted the slope, they were greeted by “a severe and galling fire” from the 7th Arkansas. McCook’s outfit, bolstered by the 10th Indiana, easily drove off the lone Arkansas regiment, and the Federals, anchoring their newly won position with artillery, stayed put on Peter’s Hill. McCook’s position overlooked a narrow valley bisected by Bull Run Creek. Confederate troops, Arkansans under the command of Brig. Gen. St. John Liddell, formed up across the valley on Bottom Hill.

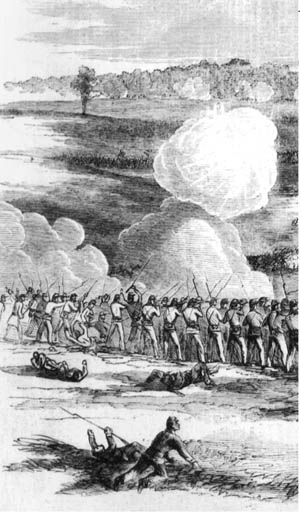

Fighting ramped up as both sides nervously felt out their opponents. Unaware that Peter’s Hill was now held by a Federal brigade, Liddell ordered his 5th and 7th Arkansas to retake the position. Union artillery fire disrupted their advance, and the two regiments broke for the rear after McCook’s men unleashed a devastating volley from a distance of 100 yards. The Confederates “wavered, broke and retreated to the woods,” recalled one Federal gunner, “It was more than they could stand.”

Sheridan Itches for Battle

Gilbert, who dashed off for direct instructions from Buell, clumsily followed up on the Confederate repulse, ordering Captain Ebenezer Gay’s cavalry brigade, without infantry support, to seize the valley. A hesitant Gay led three regiments forward with predictable results. Advancing dismounted, Gay’s troopers gave a good accounting of themselves but were worsted in a sharp fight with Liddell’s men. Gay’s outmatched horsemen, recalled McCook with dry detachment, “came back very rapidly.”

Although the skittish Gilbert was apprehensive to bring on a general engagement, his lead divisional commander, Brig. Gen. Philip Sheridan, was not so disinclined. A scrappy little Irishman who possessed a giant sized appetite for battle, Sheridan was new to division command and itching for a fight. Acting without orders, he brought up another of his brigades and promptly ordered his men to clear the valley. With “iron nerve,” thought one observer, Sheridan’s men drove into the Confederates, who broke for the rear after a brief fight. The Federals kept up the pressure, charging up to the crest of Bottom Hill. Liddell’s Arkansans, worn out after fighting all morning, pulled out.

Sheridan was eager to press the fight. “Tell Buell that they are fighting with a good deal of vim in my front,” he shouted to a staff officer, “but if he will let me go, I can drive them to hell.” Gilbert would have none of it. After consulting with Buell, the touchy corps chief pulled his troops back to Peter’s Hill and ordered Sheridan to cool his heels; the army would advance, it had been decided, only after all three corps were in place.

Spearheading the Assault on Perryville

Despite Buell’s timetable, both Crittenden’s and McCook’s corps were tardy in arriving on the field. It was roughly 10 pm before the latter began forming his men on the Federal left, on the high ground above the Chaplin River. Still determined to hit the Confederates with nothing less than the full weight of his army, Buell decided to sit tight and launch his attack the following morning. It was a reasonable decision. Sheridan had roughly handled the opposition to his front, and McCook’s senior officers were equally optimistic that the Rebels were retreating. While conferring with artillery Captain Cyrus Loomis, 3rd Division commander Brig. Gen. Lovell Rousseau remarked on dust clouds visible north of Perryville, likely an indication of Confederate troops on the move. “I guess,” Loomis offhandedly quipped, “we have tread on the tail of Mr. Bragg’s coat.”

In fact, Bragg was busy reorganizing his lines for an all-out assault on Federal forces west of the Chaplin River. Alarmed that neither Polk nor Hardee seemed eager to give battle, Bragg had personally arrived in Perryville by midmorning and was not a little annoyed that Polk, in contravention of orders, had adopted a defensive posture. Still entertaining the notion that he faced only a portion of Buell’s army, Bragg immediately ordered Polk to attack. While Hardee’s left wing kept the Federals busy immediately west of Perryville, Polk would launch a staggering attack en echelon from the right. To add punch to the planned attack, Bragg ordered his left flank division, led by Maj. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Cheatham, to pull out of line, reform on the right flank, and open the assault.

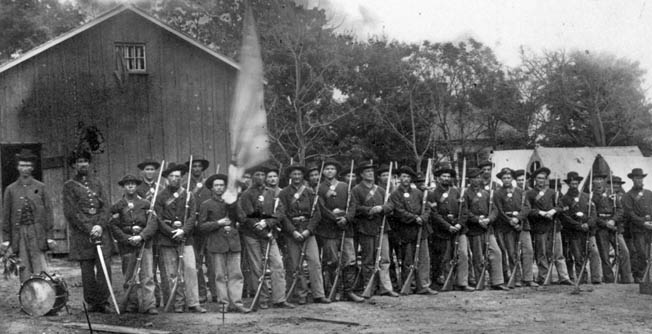

Cheatham, a political general who lacked West Point training, was nonetheless a decent choice to spearhead the assault. A foul-mouthed, bullheaded brawler, his notorious fondness for the bottle was exceeded only by his love of fighting. In preparation for the attack, a Confederate cavalry probe determined that the Federal flank lay exposed to frontal assault at a vital road junction known as Dixville Crossroads. While McCook’s Federals lounged on the Chaplin Hills and fanned out to find water, Cheatham readied his men, some of the most experienced troops in the Army of the Mississippi, to assail Buell’s left.

Woefully Inaccurate Intelligence

At half past noon, Confederate artillery opened a barrage intended to soften up the enemy position. George Landrum, who like Lieutenant Millard had unsuccessfully warned Rousseau of the proximity of Rebel troops, laughed out loud when the general and his staff scattered to escape the artillery fire. “Such a skedaddling to get out of range,” he recalled, “I never saw before.” Federal batteries responded in a thunderous duel that was heard nearly 10 miles away. As shells crashed through their ranks, McCook’s troops grew jittery. Survivors described the barrage as sheer pandemonium, but after an hour of terror Confederate artillery fire abruptly ceased and an eerie silence descended over the hills. Some of the Federals grew hopeful that there would be no fight after all and surmised that the artillery fire had been little more than a noisy distraction intended to cover a Confederate withdrawal.

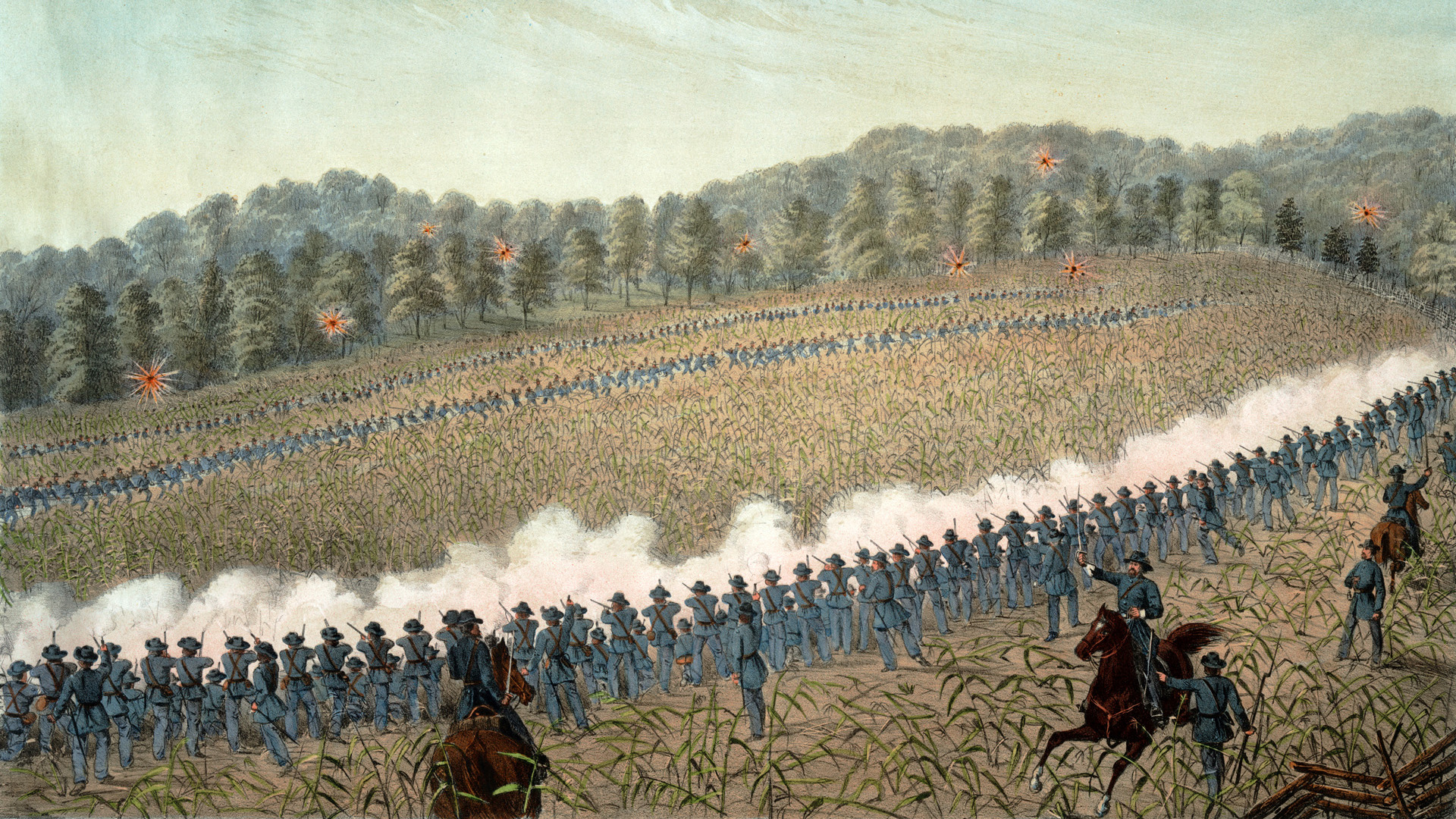

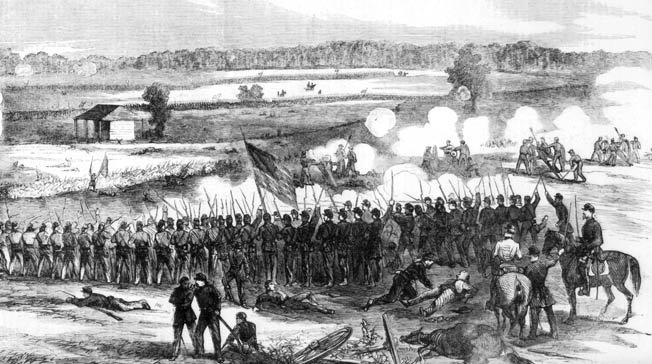

At about 2 pm, such assumptions proved sorely optimistic. Streaming out of the bed of the Chaplin River, Cheatham’s division advanced across undulating terrain that served to mask its approach until the men neared the Federal line. The lead troops, a Tennessee brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Daniel Donelson, headed straight for a Federal battery visible on the ridge line. Far too late, it became apparent that Donelson’s brigade was acting on woefully inaccurate intelligence. Rather than striking an exposed Federal flank, the Tennesseans were headed nearly for the center of McCook’s I Corps. Donelson blanched when he observed enemy artillery unlimbered far to his right on a bald hill known as Open Knob that commanded the field and anchored the Federal left. “The whole face of the earth,” thought Carroll Clark of the 16th Tennessee, was “covered with Yankees.”

Donelson’s men entered a maelstrom. The I Corps gunners subjected the Tennesseans to a merciless crossfire that tore great gaps in their ranks. The men, reported Thomas Head of the 16th Tennessee, were “mowed down at a fearful rate.” Pressing forward toward a gap in the Federal line, the Confederates desperately sought cover behind farm buildings. Cheatham scrambled to send support, while Federal regiments likewise rushed into the fight; Donelson’s attack hopelessly stalled, then fell back.

With Union troops forming on Open Knob, Cheatham shifted one of his best brigades, that of Brig. Gen. George Maney, to more advantageous ground farther to the right. Maney was a solid field commander who led a brigade composed largely of tough Shiloh veterans. An attorney in civilian life, Maney was a Mexican War veteran. He had seen action in western Virginia as well as at Shiloh. Hastily deploying three of his regiments into a front line, Maney stepped off for Open Knob.

On the summit of the hill, Federal Brig. Gen. William Terrill had deployed a single regiment, the 123rd Illinois, as well as eight guns of Lieutenant Charles Parsons’ battery. With such a skeleton force, Terrill was tasked with anchoring the left flank of the entire army. A West Point graduate and former battery commander, Terrill was far more comfortable manning big guns than maneuvering substantial bodies of infantry. Due to the rolling nature of the ground, Maney’s lead regiments escaped notice until they were a mere 200 yards from the Federal position. Frantically ordering up the rest of his brigade, Terrill directed the artillery to let loose on Maney’s line.

“Such a Storm of Shell, Grape, Canister and Minie Balls … As No Troops Scarcely Ever Before Encountered”

Firing a haphazard but deadly mix of canister, shell, and case, Parsons covered the eastern slope of the hill with a nearly impenetrable sheet of iron. Staggered, Maney’s veterans went to ground behind a rail fence bordered by a belt of hardwood. It offered some cover, but men were still dropping fast. “The battery was playing upon us with terrible effect,” remembered Lt. Col. William Frierson of the 27th Tennessee, “such a storm of shell, grape, canister, and Minie balls was turned loose upon us as no troops scarcely ever before encountered.” As Parsons’ guns splintered trees overhead, Maney’s troops lost momentum and struggled to return fire.

At the top of the knob, the 105th Ohio arrived to reinforce the hill, but Terrill seemed disinterested in directing his brigade. All but paralyzed by a myopic fixation with the artillery, Terrill took over personal direction of the guns and abruptly ordered the 123rd Illinois, a green regiment, to charge the Rebels at the foot of the hill. The results of the misguided order were tragically predictable. The Illinois rookies advanced to within 100 yards of the enemy, where the Confederates greeted them with a volley that decimated their ranks. Broken and demoralized, the frightened Federals scattered back up the hill in considerable confusion; about a quarter of the regiment had fallen in minutes. An onlooker from the 105th Ohio was left dispirited by the fruitless charge. “Such an order,” he later wrote, “was simple madness.”

An Awful Butchery

In the wake of the bloody repulse, Maney sensed an opportunity and ordered his men forward. Terrill grew frantic at the Confederate approach and again ordered a foolhardy counterattack, exclaiming excitedly, “Do not let them get the guns!” Elements of the 105th Ohio responded to the order, but the bulk of Terrill’s men remained in place as the two opposing lines blazed away at near point-blank range. “The butchery,” recalled Confederate Captain Thomas Malone, “was something awful.”

Rushing uphill the last few yards, Maney’s troops seized control of Open Knob amid the complete collapse of Terrill’s brigade. Divisional commander Brig. Gen. James Jackson, who was desperately attempting to rally his men from horseback, was shot dead during the struggle. As Union troops fled the knob, Terrill succeeded in drawing off just one of his beloved guns; his brigade had been wrecked in the vicious fight for the hill. He withdrew his battered command behind another hill to the west, an imposing ridgeline occupied by the Federal brigade of Colonel John Starkweather.

Flushed with success after seizing Open Knob, Maney’s blood was up, and he pressed his brigade forward for the next hill, optimistic that unrelenting pressure would effect a complete rout of the enemy. He would have help; on his left he linked up with elements of Brig. Gen. Alexander Stewart’s brigade, which was likewise advancing as Bragg’s planned echelon attack took shape. Hardee’s left wing also joined in, although the inevitable fog of war ensured that the Confederate thrust would be a savage and disjointed affair.

Colonel Thomas Jones’ Mississippi brigade, a painfully raw outfit, went forward prematurely. Isolated and without proper support, the Mississippians advanced gamely through a storm of Federal artillery fire, targeting a section of the enemy line occupied by the brigade of Colonel Leonard Harris. “We could see awful gaps in their ranks,” recalled Frank Phelps of the 10th Wisconsin, but the Confederates simply closed ranks and pressed on. When the attackers “got within 30 rods of us,” wrote Phelps, Colonel Alfred Chapin “called out for us to up & at them.” The Mississippians were mangled by the ensuing volley. Breaking for the rear in disorder, Jones’ shattered brigade left the hillside littered with men; nearly half the brigade was dead, wounded, or missing.

Johnson Regroups As Best He Can

Brigadier General Bushrod Johnson’s brigade advanced in even greater confusion. Johnson had received orders to oblique left to avoid Federal artillery, but not all his regimental commanders were informed of the maneuver. While most of his brigade veered south, his 37th Tennessee continued straight ahead. Before Johnson’s disjointed troops could even come to grips with the enemy, they were subjected to unexpected artillery fire that tore into their left flank. Overeager Confederate gunners, mistaking Johnson’s men for fleeing Federals, had opened fire on their own men.

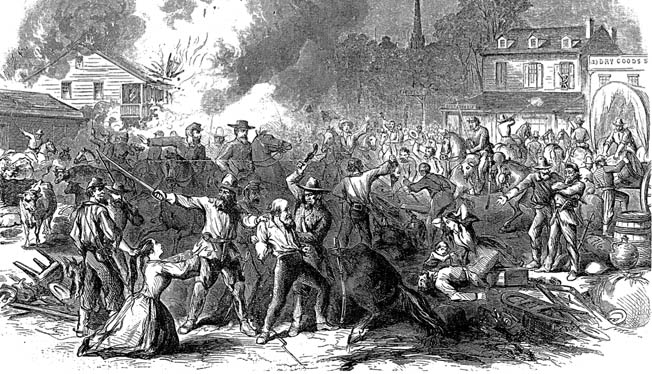

Regrouping as best he could, Johnson led his men straight for key ground on his sector of the field, the formerly obscure homestead of Henry Bottom defended by the Federal brigade of Colonel William Lytle, an idealistic warrior poet from Cincinnati who held his ground with grim determination. The horrific fighting that ensued transformed the Bottom farm into a veritable charnel house. Men fell by the score as the two lines savagely mauled each other. The Bottom barn, which was being used as a makeshift field hospital, burst into flames after it was hit by Confederate artillery. Federal wounded, unable to escape the structure, died in the inferno.

While McCook’s I Corps desperately struggled to hold onto its position, Union headquarters remarkably had no idea that the army’s left was on the verge of collapse. Due to the curious atmospheric phenomenon known as “acoustic shadow” that masked sound waves, much of the army had no idea that a major fight was even underway. Ensconced at the insulated bubble of the Dorsey House, Buell read, rested, dined rather well, and remained blissfully unaware that a third of his army was fighting for its life. At one point he had heard the faint boom of artillery and angrily snapped that such random cannonading was “a waste of powder.”

It was not until 4 pm that Buell was informed of the Confederate assault. Even then, the incredulous general remained skeptical. Focused on executing his own attack the following morning, Buell failed to grasp that the grand Confederate assault had rendered null his own plans. Due to Buell’s intransigent tunnel vision, McCook’s beleaguered I Corps was left to shift for itself.

A Brutal Reception for the 1st Tennessee

Despite their commander’s stubborn disbelief, Federal troops arrayed on the Chaplin Hills were all too aware that they were in the midst of a serious fight. Itching to break the Federal left once and for all, Maney lashed his brigade against Starkweather’s troops west of Open Knob. His attack was ably supported by the battery of Captain William Carnes, an enterprising young artillery officer who, largely on his own initiative, unlimbered his pieces on high ground above the Federal left from which he could readily pound Starkweather. His guns played havoc on the hill’s defenders; among the casualties was General Terrill, mortally wounded by shellfire while, fittingly enough, personally manning his own cannon.

As the 1st Tennessee rushed forward, Federal gunners gave the regiment a brutal reception. “The iron passed through our ranks,” remembered Private Sam Watkins, “mangling and tearing men to pieces.” It was, he thought, “the very pit of hell.” Perdition indeed waited at the top of the hill, where Maney’s men engaged the Federals in a vicious hand-to-hand struggle. Clubbing and cursing with wild abandon, the two sides fought each other to a frazzle. The battered and exhausted Confederates drew off to regroup, while Starkweather executed a skillful retreat and regrouped. He chose his ground well, rallying his brigade on an imposingly steep ridge that would afford his troops a decided advantage. Hastily forming behind a stone fence, Starkweather’s men poured a steady fire into the Confederates. Although supported by Stewart’s brigade on the left, Maney’s spent troops stalled and reluctantly fell back. They had beaten in I Corps’ flank for nearly a mile but had reached the limit of their endurance. Thanks to Starkweather’s stubborn stand, the Federal left had held.

Whether or not the rest of I Corps could hold fast was yet to be decided. Although Lytle’s brigade had narrowly held its own against Bushrod Johnson’s Confederates, it was soon assailed by overwhelming force. While the Rebels kept up pressure on both of Lytle’s flanks, a fresh enemy brigade appeared to his front. Composed of Tennessee and Arkansas veterans of the Shiloh campaign, the outfit was led by one of the most promising officers in the western theater, Irish-born Brig. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne.

The Confederate Juggernaut Finally Slows

Moving forward at double time, Cleburne’s men tore into the enemy at nearly the same time that Lytle’s Federals, running low on ammunition, pulled back from the ground they had so tenaciously defended. One Louisianan paid grudging homage to the Federals’ grim dedication. Corpses in blue appeared “in two straight lines as they had fallen. I could have walked on their bodies without touching the ground several hundred yards. Scarcely a man could be seen out of his place in the line.” During the chaotic retreat, Lytle sustained what he initially feared was a mortal head wound and was captured by the onrushing Confederates.

Sweeping Lytle’s brigade out of the way, the Confederates made a determined drive for the Dixville Crossroads. Cleburne, advancing parallel to and north of the Mackville Road, linked up with Adams’ brigade, which moved forward on his left. The Confederates crashed into a makeshift line composed of the 42nd and 88th Indiana, driving off the Hoosiers after a brief but bloody fight and pressing on toward their objective.

Despite such success, the Confederate juggernaut was losing momentum in the face of stubborn Federal resistance. As dusk approached, reinforcements arrived to relieve the battered I Corps. Gilbert released Colonel Michael Gooding’s III Corps brigade just as Rousseau’s thin and exhausted line was assailed by the Confederate brigade of Brig. Gen. Sam Wood. Directing the newcomers to the scene of the thickest fighting, McCook was clearly relieved. “I think this brigade,” remarked the embattled corps commander, “will turn the scale.”

Racing into action, Gooding’s troops pitched into the Rebels and plugged the gap at Dixville Crossroads. The battle raged furiously, thought Gooding, as “one after one of my men were cut down.” In something of an understatement, the colonel reported that his fresh brigade “severely pressed the enemy.” In fact, his troops nearly folded up Wood’s right, and Gooding’s 22nd Indiana mounted an impetuous bayonet charge into the 32nd Mississippi. The action initiated a contagious rout of Wood’s brigade, which hastily fled the field. The Hoosiers, in turn, were greeted by an unexpected volley that sent them reeling. Deployed directly in their front, and coming on for the crossroads, was Liddell’s Confederate brigade.

Since opening the battle early that morning during the nasty tangle with Sheridan’s men, Liddell’s Arkansans had rested and regrouped before they were called on once more. General Hardee desperately sought fresh troops to throw a final punch at McCook’s fragile line. Polk and Cheatham, on hand as Liddell’s men went into action, were sure that the brigade could finally break through to the crossroads. Under simple orders to go where the fire was hottest, Liddell wryly remarked that on the blood-soaked fields of Perryville the hottest place “seemed to be everywhere.” As darkness descended over the battlefield, Liddell groped his way toward the crossroads, unsure if there were friendly troops between him and the enemy. When his men opened fire on unidentified troops to their front, they were answered with a desperate call to cease firing. “You are firing upon friends,” someone shouted, “for God’s sake stop!”

Liddell was not the only disoriented soldier on the field that evening. The order to cease firing had come from an officer of the 22nd Indiana, who was convinced that his own regiment had bumped into another Federal unit in the darkness. Polk, riding to the front, was equally concerned lest Liddell precipitate a friendly fire incident. Determined to sort it out, Polk brazenly rode up the ridge to have a look for himself.

“I’ll Show You Who I Am, Sir…”

What followed was one of the more legendary cases of mistaken identity in the Civil War. Polk happened upon a somewhat befuddled officer and barked orders to cease firing. When the officer announced himself as the commander of the 22nd Indiana and then asked Polk’s identity, the corps commander blanched at the news but responded with stark bluster. “I’ll soon show you who I am, sir,” he shot back. “Cease firing, sir, at once.” Coolly riding back to his own lines, Polk repeatedly snapped orders to cease firing. His bluff paid off; the confused Hoosiers let him pass. Reaching the safety of Liddell’s line, Polk bellowed out his discovery. “Every mother’s son of them,” he exclaimed, “are Yankees!”

Liddell’s brigade opened up on the unprepared Federals with a point-blank volley that put the shocked Hoosiers to flight; two-thirds of their number were left lying on the ridge. When Confederates began pouring through the gap thus created, the rest of Gooding’s brigade retreated beyond the Benton Road. Sensing that victory was within reach, Liddell advanced his brigade to Dixville Crossroads, occupied the vital road junction, and readied for a final push against the demoralized remnants of I Corps.

He would never get the chance. Federal troops could be heard forming off to his left. It was a second and final brigade of reinforcements rushed to the scene by Gilbert, under the command of Brig. Gen. James Steedman. Liddell, convinced that he could break the Federals once and for all, was eager to press the fight. But Polk, rattled by his uncomfortable brush with the 22nd Indiana, would have none of it. He directed Liddell to sit tight. “I want no more night fighting,” the bishop announced.

As it turned out, Bragg wanted no more fighting—either night or day. Contrary to Bragg’s repeated assertions that Union forces in front of Perryville constituted no more than an isolated detachment of Buell’s army, the day’s fighting had obviously demonstrated that the Federals were present in strength. Operating southwest of town on the Lebanon Pike, Wheeler’s cavalry had sparred with elements of Crittenden’s II Corps, and elements of Gilbert’s III Corps had made a late afternoon dash for Perryville itself, indicating that a sizable Federal force lay immediately west of the town. The day’s fighting had been excruciatingly costly for Bragg’s army. Nearly a third of his available force was dead, wounded, or missing. With no fresh troops at hand and no help expected from Kirby Smith, Bragg decided to abandon the ground for which his men had paid dearly in blood.

Horrific Losses, Largely in Vain

At the Dorsey House, Buell remained oblivious to the magnitude of the day’s battle. The starchy general persisted in his belief that the fight had been a middling affair and failed to grasp that McCook’s I Corps had been thoroughly mauled. Sheridan, who dined at headquarters that night, was startled by the army commander’s stubborn refusal to acknowledge the obvious—that a major fight had taken place. Dinner conversation, thought Sheridan, “indicated that what had occurred was not fully realized, and I returned to my troops impressed with the belief that general Buell and his staff-officers were unconscious of the magnitude of the battle that had just been fought.”

Sheridan was not far off the mark. When II Corps entered Perryville at midmorning on October 9, they found the town deserted. Under cover of darkness, Bragg had pulled out. With the Rebels gone, the Federals were left in possession of a field littered with dead and wounded, and Buell was finally confronted with the staggering cost of I Corps’ stubborn stand.

Both sides had suffered heavily in the fighting. Buell had lost at least 4,200 men: 845 killed, 2,851 wounded, and 515 missing. Proportionately, the Army of the Mississippi fared even worse: 510 killed, 2,635 wounded, and 251 missing. During a single afternoon of fierce fighting, Bragg had lost 20 percent of his available troops. Burial details labored for days at the unenviable task of interring the dead. John Sipe of the 38th Indiana, who had volunteered for the duty, hoped that he would “never witness the like again.” Blue and Gray were scattered promiscuously, he wrote his wife, “with their limbs blown off or shattered to pieces. One Rebel with both his arms blown off told me if he were in his grave he would not suffer so.”

It soon became apparent that such horrific losses had largely been in vain. As the Army of the Mississippi limped away from Perryville, Bragg quickly reached the conclusion that the campaign for Kentucky was over. Whatever chances he had once had for uniting with Kirby Smith and offering battle on his own terms had clearly evaporated. Considerably diminished by the battle at Perryville, the Confederates were in no shape to confront Buell again. By October 13, both Bragg and Smith, united at last in retreat, had their men on the move for Tennessee.

Slogging their way through the parched hills of eastern Kentucky, the demoralized Confederates made their way through Cumberland Gap to Knoxville. Defeatism infected the officer corps. In the wake of the Battle of Perryville, the army’s senior officers sought to apportion blame for the embarrassing debacle. A host of generals, including Smith, Polk, Hardee, Buckner, Cleburne, and Liddell, angrily called for Bragg’s ouster.

Unsettled by such insubordinate gossip, President Davis ordered Bragg to Richmond for a firsthand accounting of the disaster. Bragg put on a brave face, casting blame for Perryville in every direction but his own. Ultimately the president rallied to the defense of his old friend, retaining Bragg in command of the army. Despite the shakeup, the bitter controversy and mutual recriminations spawned by Perryville continued to fester, ensuring that the army’s senior command would degenerate into a fractious gaggle of quarreling officers. The crippling distrust naturally filtered down to the men in the ranks, and Bragg labored under a black cloud that would dog him for the remainder of the war. “Not a single soldier in the whole army ever loved or respected him,” recalled Sam Watkins, and the troops “had no faith in his ability as a general.”

“Both Sides Claim the Victory—Both Whipped”

Buell fared little better in the court of opinion. Already out of favor with the Lincoln administration in the weeks leading up the Kentucky campaign, Buell’s fate was nearly a foregone conclusion after his nonperformance at Perryville. His actions subsequent to the battle didn’t help matters. With Bragg’s army in full retreat toward Cumberland Gap, Halleck unsuccessfully prodded Buell to mount a vigorous pursuit. He simply shrugged it off, opting to concentrate his forces at Nashville. “I deem it useless and inexpedient,” he wired Halleck, “to continue the pursuit.” For an exasperated Lincoln, such blatant disregard for orders was the last straw. At the end of October, Buell was relieved of command.

Ultimately, the bloody fight at Perryville came to be regarded as a senseless waste of brave men. Bragg had flushed Buell out of Tennessee and shifted the front, albeit temporarily, to the Ohio River, but the entire campaign had been a misbegotten affair from the outset. Without a rational end game, Bragg’s headlong drive into the Bluegrass State had mystified both the Federals and his own men. The “whole tour through Tenn & Ky,” wrote Edward Brown of the 45th Alabama, “is a foggy affair to me.” Once battle was joined, neither Bragg nor Buell possessed a clear grasp of the situation. More damningly, both generals were disengaged from the fight, leaving more than 35,000 men to slug it out on their own. The indecisive results of the battle were a sobering testament to the bitter fruit of maladroit generalship.

For the common soldiers who had grappled there, Perryville remained a tragically senseless affair. Sam Watkins, whose 1st Tennessee had seen some of the worst fighting on the Federal left, was dispirited by the pointless and bloody stalemate. His own homespun assessment of the engagement was likely the most accurate. “I do not remember of a harder contest and more evenly fought battle than that of Perryville,” he wrote. “If it had been two men wrestling, it would have been called a ‘dog fall.’ Both sides claim the victory—both whipped.”

Interesting…always wondered about what happened at Perryville; had a family member, James Fowler, of Wheeler’s Cavalry/4th Tenn., captured at Perryville.

Thanks for the article.

Thos. B. Fowler

Abilene, Texas