by Jonathan North

[Editor’s note: The following are participant accounts—mainly those of Alfred Armand Robert Saint-Chamans—of Napoleon’s 1813 campaign in Germany ending in the decisive battle of Leipzig. The commentary and major translations are by British author Jonathan North.]

[text_ad]

Injuries Take Saint-Chamans Off The Battlefield

Count Alfred Armand Robert Saint-Chamans, colonel of the 7th Chasseurs à Cheval by 1813, was a distinguished light cavalryman who fought in all the major Napoleonic campaigns up until 1814. His account of Napoleon’s 1813 campaign in Germany gives a superb insight into the Grande Armée as it goes from bad to worse—emerging from the disastrous Russian adventure and being rebuilt in the spring of 1813, then to face a severe trial at Leipzig (the “Battle of the Nations”) in October.

Although he was a light cavalryman—a branch of the service associated with glorious exploit, brilliant uniforms, and all the glory of the Napoleonic epoch—Saint-Chamans’ account of his campaigns is very different from the memoirs of such gallant and dashing heroes as Marbot and Parquin. This is particularly true of his relation of the 1813 campaign. After having watched his regiment being destroyed in the snows of Russia and then fleshed out with untested conscripts in February 1813, Saint-Chamans is weary of war and the seemingly pointless sacrifice of French blood. Added to that is the fact that 1813 was, for Saint-Chamans as well as for many other French officers, a bad year. Because his troops were green and inexperienced, he evidently felt it his duty to expose himself more and encourage them by leading from the fore. As a result he was badly wounded twice in two months—and this was on top of a nasty lance wound he had received in Russia.

Saint-Chamans Returns To Active Duty

War was evidently beginning to take its toll.

For Saint-Chamans, returning to active duty after his convalescence and after a brief period of time at the regimental depot—a number of colonels were posted to their respective depots to hurry the influx of new conscripts along—the campaign opened in July 1813, after the French victories at Lutzen and Bautzen:

I was given the order to present myself at Freistadt, a little town in Silesia occupied by my regiment. On the 15th July I rejoined my squadrons. My regiment belonged to Sebastiani’s cavalry corps and, as I had known this general when he had been colonel of my regiment, we got on very well. He commanded some 90 squadrons and 30 cannon; my regiment was part of Exelman’s division.

The Army Needs To Mature…

Saint-Chamans found that the regiment, which had suffered heavily in Russia as part of II Corps, was in poor shape. Indeed this was true about all French cavalry regiments, even including those that had not gone as far as Moscow, and of the Imperial Guard regiments. So bad was the situation concerning the cavalry that, in February 1813, General Bourcier commented to the Minister of War that, “They might as well have excluded the cavalry from the inspection. The survivors of 1812 are too few to bother counting.” Saint-Chamans comments on the standard of the new recruits and the situation in the army generally:

This cavalry appeared to be very good but, as was once said about the Great Condé’s army, it needed to mature. Indeed neither the men nor the horses had ever been to war: the former were twenty years old and the latter were four—it was said that they were chickens mounted on colts. The troops wanted very much to face the enemy but this sentiment fell apart as soon as they began to feel the fatigues of life on campaign.

The infantry were in much the same way; they were brave but had little staying power. We had, motivated by French honour and enthusiasm, carried the day at Lutzen and Bautzen and should have called a halt there—these victories had been enough to secure a glorious peace. Then we should have pulled our troops back to the Rhine, placed them in camps, like that at Boulogne, for two years. After that we could have dictated our will to Europe, as we had done of old.

“Busy Yourself With The Instruction Of Your Troops”

The cavalry regiments had to be raised from scratch and new horses found to replace those lost in Russia. Many of the conscripts pressed into the mounted arm had little or no experience of riding and it was hoped—with considerable wishful thinking—that they would learn their trade en route or, if necessary, in battle. Napoleon’s cavalry would remain weak throughout 1813, a fact recognized by the emperor when he instructed his corps commanders to force his infantry to practise forming battalion squares as much as possible, thus to ward off the stronger enemy cavalry. He wrote, for example, to Lauriston, “Busy yourself with the instruction of your troops. Above all, maneouvres of change of formation from attack column to square and back are recommended.”

Napoleon was well aware of the weak state of his new army, particularly the cavalry, and resorted to reviewing and inspecting the troops as much as possible and lavishing decorations—and extra rations, as Parquin recollected—upon them with the aim of encouraging the young soldiers before they faced the oncoming trials and tribulations. Saint-Chamans describes one such review, held in the fall of 1813:

“Show Me Some Veterans Of ’93”

On the 28th September the emperor passed my regiment in review. Our situation was dire and he seemed to recognise this. He encouraged us and made a number of complimentary remarks. My regiment numbered 300 men, although, five weeks previously it had had twice that number, but Generals Sebastiani and Exelmans eulogised about the regiment’s performance:

I presented to the emperor those officers whom I felt deserved promotion to captain, lieutenant and, then, presented a number of young men whom I thought would make excellent second lieutenants.

“I don’t need these young ones,” he told me warmly, “show me some veterans of ’93.”

I didn’t quite understand and stood there in confusion.

“Yes, show me some veterans of ’93.”

I turned and brought forward some old sergeants, as incapable as they were ancient. He charmed them, without questioning them—just as well as if they had managed to answer his questions they probably would have uttered some nonsense and shown the emperor the error of his ways.

After the promotions, he declared that he wished to award the Legion of Honour and that I should prepare a list of deserving individuals.

Prussians Open Fire On Saint-Chamans

Thus the emperor did his best to motivate the troops and correct some of the more obvious failings. The soldiers responded well at Lutzen and Bautzen, but the French lacked the cavalry to pursue and make the victories decisive. Light cavalry, as they proved in 1806 against the Prussians, excelled at pursuit. But such an opportunity was rare, notwithstanding what Marbot and Parquin suggest in their memoirs, and Napoleonic campaigns offered few all-out death-or-glory charges. For the most part, light cavalry were involved in the more routine tasks of reconnaissance and skirmishing, as Saint-Chamans describes:

On the 5th September we found ourselves trailing an enemy formation. I had gone on ahead with my skirmishers to reconnoitre the terrain and to see whether or not we could launch a full-blown charge on the enemy position. At the entrance to the Reichenbach defile I noticed a regiment of hussars coming up on our flank. “They are Prussians” I said to Dubois, my adjutant, who was right beside me.

“No, colonel, they are French,” he replied, “they must have come another way and are coming over in our support.”

I repeated my fear that they were Prussians. He was certain they were French; all the time they got nearer. Suddenly, when they were only some 80 paces away, a dozen of them separated from the main body and rode on ahead.

“Look, they are Prussians,” I shouted to Dubois. I spun my horse around just as he cried out to the horsemen “Don’t shoot, we are French!” he had barely uttered the last word when they opened fire with their carbines; a ball went into my colback [a round, fur hat worn by chasseur officers] and another struck me in the lower abdomen and almost knocked me out of my saddle. I managed to tell Dubois to fall back as I was wounded.

We regained our ranks and the enemy fell back. Lawoestine, Sebastiani’s aide-de-camp came up and helped me off my horse. Later, the doctors examined me and found that the bullet had in fact struck my pocket watch, which had absorbed much of the impact, and had then driven a fragment of my watch into my abdomen. This caused me tremendous pain and vomiting. However, after a little while, I felt sufficiently well to resume the command of my regiment. I would have preferred to rest, but I knew that my chasseurs thought me killed, which had affected their morale and endangered them, and I felt that my place was at the head of my regiment.

The Battle Of Leipzig: Deciding Gemany’s Fate

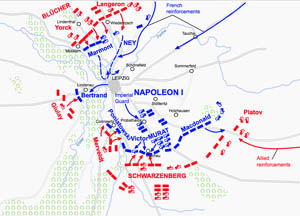

And so the 1813 campaign went for Saint-Chamans, an endless cycle of gathering information, patrolling, and skirmishing, until October 1813 when his regiment was recalled to the main army in preparation for the biggest confrontation of the Napoleonic Wars—the epic battle of Leipzig. Napoleon’s second attempt to capture Berlin had failed and he now sought to lure the Allies toward him and defeat them in detail. He misjudged the situation and was soon to find himself attacked simultaneously from the north, as Blücher crossed the Elbe at Wartenburg, and the south, as the Austrians bypassed Dresden and advanced. Napoleon, fielding 175,000 men was to be opposed by 335,000 Russians, Austrians, Prussians, Swedes, and Germans in a battle that would decide the fate of Germany.

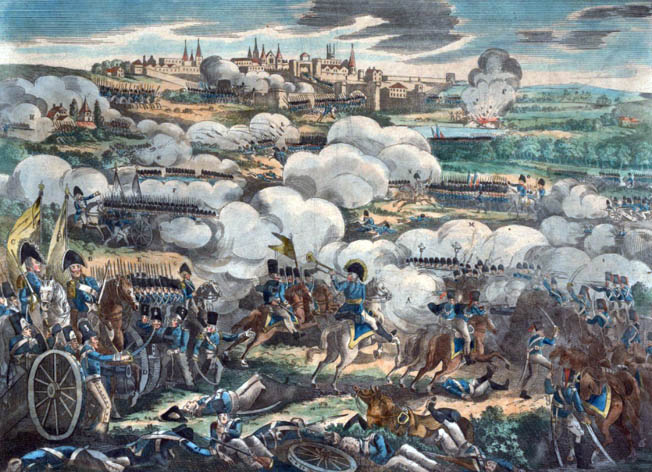

The battle began on October 16 with skirmishing as the two sides established themselves and drew themselves up for battle. The Allies under the dull Austrian, Schwarzenburg, confident in receiving reinforcements, made ready for the offensive while Napoleon and his army, relying on Allied fear of the emperor and French elan, also sought an aggressive stance. Saint-Chamans found his regiment quickly placed in the frontlines as the armies marked out their positions for the coming struggle:

We arrived at Leipzig on the evening of the 15th October, a Thursday. Everything suggested that the decisive confrontation of the campaign was about to be fought and that the battle, when it happened, would be terrible. On the 16th, at dawn, our division rode forward to relieve some squadrons of guard cavalry placed at the outposts. My regiment was to the fore and we took over from the Guard Chasseurs. We were placed opposite a regiment of Austrian hussars, separated from us by a small stream. They didn’t seem to want to cross the stream and challenge us and we were content to keep the status quo. So we established ourselves and settled down to watch one another, waiting for the order to come so that we could get at each other’s throats.

“We Would Have To Fight On An Empty Stomach”

General Boyer, an old friend of mine and now a cavalry general, was established with his brigade in a little village—possibly Taucha—quite near to our own camp. He asked me over to share with him a pâté and a few bottles of white wine. A pâté! I hadn’t seen one of those for the last three months. It was eight in the morning, I was dying of hunger. I went. The pâté was shared out between twelve of us, but just as we were about to bite a terrible and fierce bombardment began; we rushed to our horses and it looked like we would have to fight on an empty stomach, something repulsive to any Frenchman but something which was happening a lot in our army.

Parquin, in the Guard Chasseurs, also remembers that terrible bombardment which marked the beginning of the “Battle of the Nations”:

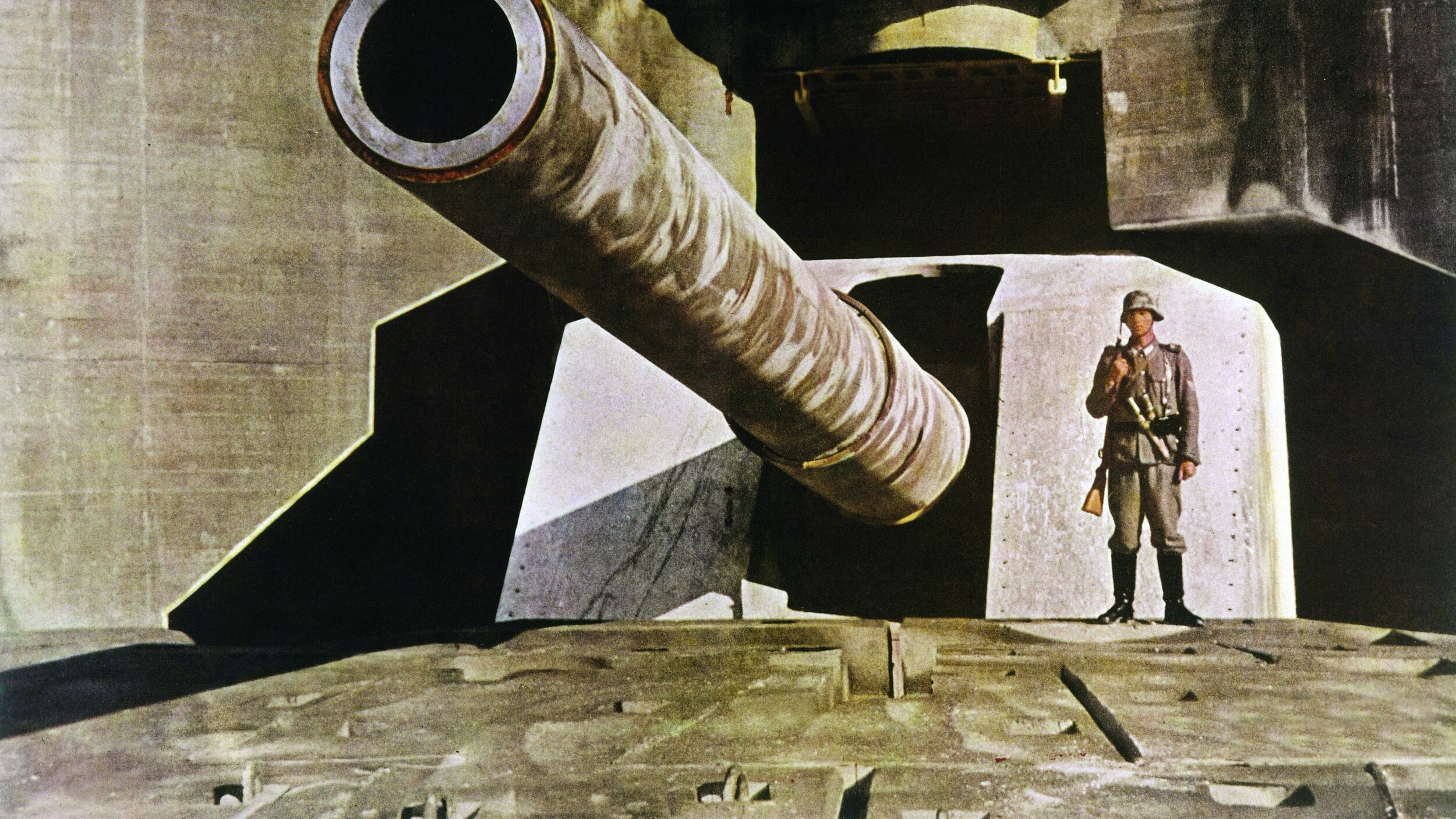

On 16 October at nine in the morning, the action at Wachau, which occupied the first day of the battle of Leipzig, began. The cannonades from the enemy artillery were the signal for the start of a terrible bombardment by 200 guns, and cannon-balls rained down upon us. The Guard cavalry was placed in the centre of the army. I can still see General Drouet standing in front of us, indefatigably directing the fire of the Guard artillery. I was to lose one of my friends, a lieutenant in the regiment whose name was Henneson. He was hit full in the chest by a cannon-ball. After shattering his stomach the missile lodged in his cape which he had slung diagonally over his back.

“The Allied Army Marched Against Us At All Points”

Marbot, a colonel in the same division as Saint-Chamans, the 4th Light Cavalry Division, also remembers the bombardment, the first of many over the coming days as the Allies were to deploy their 1,456 guns to maximum effect:

On October 16th at eight in the morning, the allied batteries commenced firing. A brisk cannonade opened all along the line, and the allied army marched against us at all points.

Hearing the battle commence, Saint-Chamans, a responsible and professional soldier, arrived back to find his regiment in a state of confusion, somewhat bewildered by the scale of events taking place:

Allied Barrage Wounds Saint-Chamans

I arrived and had my regiment mount and form up for action, the Austrian hussars having done the same. The bombardment seemed particularly fierce on our right, but we forced ourselves to concentrate on matters to our front. To kill some time, we sent out some skirmishers to exchange shots with the Austrians. We were quite weak on this particular part of the battlefield and the Austrians knew this. They brought up a battalion of infantry, which opened a galling fire on us, quickly followed by a battery of artillery, which was still worse. They shot so well that every missile found a target—I lost so many men and was powerless to fight back, something which hurt a great deal. Things got still worse and disorder began to appear in our ranks; horses were hit, others shyed away or reared up in fear, and a number of men dismounted in order to help wounded comrades to the rear. Nevertheless the men were showing courage and were standing up to their ordeal; still, I felt it necessary to show a good example to them and rode up and down in front of the regiment shouting encouraging words.

As I was doing this, I suddenly felt myself lifted out of my saddle and I came crashing to the ground. I lost consciousness.

A cannon-ball had grazed me, hit my leather pouch and driven it into my chest, without, fortunately, hitting me full on. But it caused me immense pain and would continue to do so for many years yet. In fact, I still feel it now.

When I came to, I found that they were carrying me in a cloak to the nearest village, that same village which, two hours previously, I had almost feasted on the pâté. My mouth felt horrible and I spat into my hand; I was horrified to see that I spat blood. I felt that my death was now certain, I was in agony and was sure that it was all going to be over in a matter of hours.

Death In A Few Moments…

I had the regiment surgeon with me and he was accompanied by another gentleman of the same learned profession (from the 23rd or 24th Chasseurs); despite their assurances I could see that they were troubled. Finally, after a thorough examination they decided that I had a massive contusion and that they would have to bleed me. I thought they were wasting their time and told them so, I would be dead in a few moments.

The village was in danger of being stormed by the enemy, the firing was getting closer and our troops were being pushed back. They decided it would be better to get me to Leipzig itself, about six miles away. They loaded me onto a stretcher covered in straw and, as I screamed my agonies, carried me off. I was racked by pain which attacked me from the base of my spine to my neck.

We made slow progress and, just as we entered a large village three miles from Leipzig, we saw a host of wounded who told us that the road to Leipzig had been cut by a swarm of cossacks. I was set down in a still occupied house. I began to vomit clots of blackish blood and I felt so bad that I begged those who had carried me to put an end to my sufferings. Luckily, they refused to do this.

Injured Saint-Chamans Taken To Leipiz

Towards evening we were told that the road had reopened and that we could press on to Leipzig. The enemy had been pushed back and his cavalry had been forced to withdraw. I therefore arrived in the city at around eight or nine in the evening and I was taken straight to some quarters prepared in advance. I was still in agony and convinced that my ribs must all have been broken. I once witnessed, at the battle of Ocana in Spain, one of my friends suffering from a similar kind of wound; he had spent two or three days in agony before his eventual death.

I did not sleep that night, I was kept awake by the pain and by the fever, although I was very weak from loss of blood. I worried about the pain and I was terrified that if the French army was forced to withdraw I would be abandoned as I was in no fit state to be transported. What would become of me? The 17th and 18th went by and the agony continued. The pain was not going away and even such a simple thing as a wash down with eau-de-cologne was unbearably painful.

Napoleon Decides To Begin Retreat

As Saint-Chamans lay wounded, the battle was not going well for Napoleon. The 16th had been something of a draw, the Allied assaults had been beaten off and the French held their positions all along the line. The 17th saw the arrival of 18,000 French reinforcements under Reynier, while the Allies were joined by 40,000 Russians under Benningsen and 60,000 men under Bernadotte, one-time marshal of France, now Crown Prince of Sweden and enemy of Napoleon. On the 18th, Napoleon witnessed the desertion of his Saxon allies. He committed his Guard and his army withstood repeated Allied assaults. The Allies were now attacking concentrically and coming on in huge masses, supported all the time by an onslaught of artillery. Characterised by French heroism and Allied lack of imagination, Leipzig was nevertheless turning against Napoleon as weight of numbers began to tell. On the morning of the 19th the French, bowing to inevitability, began their retreat over the single Elster River bridge:

Finally, at dawn on the 19th, we learnt that the French army would commence a full retreat; I also heard what had happened to my regiment—it had been completely destroyed, less than 100 men remained and of the 22 officers present on the morning of the 16th, 13 had been killed or wounded. (Killed: Dubois, Grandin, Duboismande, Bontin, Vangrasweld, Castel. Wounded: Saint-Chamans, Vieillageux, Larderet, Veniere, Boussi, Michonnet and Mesplies.)

Marbot too remembered his losses:

I was able to look at our regiment in detail, and learn the losses caused by the three days’ fighting. I was horrified to find that they amounted to 149, of which sixty, including two captains, three lieutenants, and eleven NCOs, were killed; a terrible proportion out of 700, which had been the strength of the regiment on the morning of the 16th. Nearly all the wounds were caused by grape or round shot, which unhappily allowed small hope for recovery.

“It Was Dismal, Painful, Cruel”

The French were indeed falling back as fast as they could. After a ferocious struggle in which they had lost some 95,000 dead, deserted, and wounded, Napoleon had decided to save what he could of his honor and his army. Jean-Baptiste Barrès, of the Imperial Guard Foot Chasseurs, reflects on the horror of the battle and the prospect of retreat:

It was dismal, painful, cruel. The grief at having lost a great and bloody battle, the frightful prospect of a morrow that might be still more wretched, the guns raging at every point of our unhappy lines, the defection of our cowardly allies, and lastly the privitations of every kind that had for days been crushing us: all these ills, all these causes taken together, made me reflect bitterly indeed upon war. We lost the majority of the officers and more than half the men. I had not twenty men left of the two hundred and more who had answered the roll since the beginning of this campaign.

Admitting defeat, the French began to pull troops back from the fighting line and send to the rear the trains and baggage of the army. Then, in a phased withdrawal, the troops began to march westward. It was confused and, harried by Allied armies and shelled by Allied artillery, the remains of Napoleon’s army crammed the narrow streets of Leipzig, the Saxon city. Barrès paints a startling picture of the scene:

The boulevards were choked with guns, baggage wagons, travelling carriages, carts, canteens, horses, etc., we could go no further, so complete was the disorder and pell-mell confusion. I followed the stream of fugitives and crossed the bridge, whose entrance was blocked by an iron grille and littered with corpses, which were being trampled underfoot.

Saint-Chamans Must Be Moved From Leipzig

French troops were still flooding through the city, abandoning everything. Saint-Chamans continues his story:

Marshal Augereau arrived and posted several companies of grenadiers around the house. Soon it became evident that I wouldn’t be able to stay here much longer and I was carried, by four grenadiers, to the Hotel Bavaria (in Peterstrasse). I was still spitting blood.

I was in something of a stupor, and things were happening so quickly, that I was at the heights of confusion. My cousin, Count Louis de Saint-Chamans, a lieutenant in my regiment, had not left me since my wound and Doctor Denoix was still with me, as was my valet.

Becoming Prisoners Of War

It was now obvious that we were to become prisoners of war. My companions in misfortune therefore busied themselves in hiding our money and valuables, leaving just one purse containing 2 or 300 francs in view: sufficient to satisfy the greed of the soldiers and spare us the abuse which was certain to follow if we didn’t offer them anything. When everything was ready we awaited our first callers; just one thing worried me: that they might search under my matress and, in so doing move me and cause the pains to begin anew.

Marbot confirms that the fate of those French abandoned in Leipzig was likely to be horrible:

The most terrible moment of a retreat, especially of a commanding officer, is when he has to leave his wounded to the mercy of the enemy, who often have none, but plunder or put an end to the unhappy men who are unable to follow their comrades. However, as the worst thing of all is to be left lying on the ground. I had all my wounded taken up under cover of night and collected in two neighbouring houses, both to remove them from the first fury of the enemy, who would be flushed with wine, and to enable them to aid each other, and keep up each other’s courage.

French Soldiers Chose Death Over Capture

That moment of reckoning was approaching for Saint-Chamans. The Allies began their final assault on the city at seven on the morning of October 19 and by 11:30 they had broken into Leipzig’s suburbs. The Grimma Gate into the city was stormed, with much loss on both sides, and the French pushed back into Leipzig itself. Individual blocks, isolated houses resisted, but the Allies pushed on, overcoming all pockets of desperate men and driving for Elster bridge. Tragedy occurred when an engineer, Corporal Lafontaine, blew the bridge prematurely as he came under fire from Allied skirmishers. The destruction of the bridge did not end the fighting. The French trapped in the city continued to put up an all-too-desperate resistance for perhaps an hour. The destruction of the bridge did seal the fate of a large number of unwounded French troops as Marshal Macdonald, commanding the rearguard, and who managed to swim the river, remembered. Here he describes the scene after he had crossed the river and as he turned back to see those troops cut off and trapped in Leipzig:

On the far side of the Elster, the firing continued; it suddenly ceased. Our unhappy troops were crowded together on the river-bank; whole companies plunged into the water and were carried away; cries of despair rose on all sides. The men perceived me. Despite the noise and the tumult I heard the words “Marshal, save your men! Save your children!” I could do nothing for them. Overcome by rage and indignation, I wept. Unable to give any assistance to these poor fellows, I quitted the scene of desolation.

For a long time I was haunted by the terrible picture and the cries of my men still ring in my ears, and excite in my breast the deepest pity for the poor fellows whom I saw throwing themselves into the water, preferring certain death to the risk of being massacred or taken prisoner.

Injured Face Terror As Allies Move In

Some 20,000 men had been cut off. A few, such as Macdonald, swam. Many, including Marshal Poniatowski, drowned in the attempt. The rest were forced to lay down their arms, surrender, and become prisoners of war. Besides these unwounded troops, the French had also abandoned the thousands of wounded, lying in improvised hospitals or in houses scattered across the city. They too were about to find themselves captives, an uncertain situation in any war but one of especial uncertainty in the inner recesses of a city just taken by storm after a gigantic four-day struggle. Saint-Chamans, in his sick bed in Peterstrasse, takes up his story just as the Allied troops make their presence as conquerors felt:

Shooting broke out in the street, under my window, and from the “Hourras” of the Russians it became obvious that the Allies were now masters of the town. Just then we heard a commotion in the corridor. The doctor ran out to find the hotel owner being threatened by a French officer. The officer wanted bread and was about to run the hotelier through when the doctor intervened and the officer fled.

Prussians Seek Money, Jewelry

It was then that a party of Prussian grenadiers appeared; they came into the room with their bayonets lowered as though prepared to take the place by assault. One of them, some kind of NCO and their evident leader, demanded in German:

“Are there any French here?”

“We are all French.”

“Money?”

The doctor presented him with the purse, prepared beforehand; he looked into it and seemed satisfied with what he saw. He put it into his pocket and said in French :

“Watches!”

The doctor gave him his; my cousin gestured that he did not have a watch; my valet was shivering so much that he was incapable of speech or gesture.

They seemed satisfied by their small haul and they went out without having even touched our portmanteaus or our weapons. We were realistic enough to guess that this would not be our last set of visitors; we learnt that a party of Russian generals had moved into the building and the doctor went off to see them in order to ask for their protection:

“Do not worry,” said the general, “nothing will happen to you, I have issued severe orders to suppress looting and prisoners will be well treated.”

“But,” said the doctor, “we have already been pillaged.”

“That is impossible,” replied the general, “because we have made such an offence punishable by death; please be reassured.”

“Those Thieving Prussians! They Are Brigands!”

They escorted him back to our door. We were in fact left in peace until around ten in the evening. My companions had just lain themselves down to rest when there was a loud banging on the door. We were obliged to open the door and a cossack officer, utterly drunk, staggered in. The cossack and the doctor had the following conversation, uttered in bad German, and I translated for the benefit of my cousin and valet:

“Give me money,” said the officer, “I want money.”

“We’ve got nothing; the Prussians took it all this morning.”

“Those thieving Prussians! They are brigands! So, you have got nothing for us?”

“Unfortunately, we have nothing. And here is the colonel, wounded badly, and deprived of everything.”

“Those thieves,” continued the cossack, “those bandits; but you must have something for us.”

“Look around for yourself. We have nothing but the clothes we are dressed in.”

“Prussian robbers! But,” finding the hilt of my sabre, “here is some gold.”

“That is the colonel’s sabre.”

“The colonel is a prisoner and doesn’t need it anymore. It is a good sabre, and I need one … Do you have anything else we might like?”

“Nothing at all.”

“Those robbers!” said the cossack opening the door, with difficulty, “I’ll find them and make them pay.”

Fearful Prisoners Seek Protection

The rest of the night passed without incident. Nevertheless we felt it necessary to place ourselves under the protection of someone with power and influence.

We wrote a letter to some Austrian generals, asking to become prisoners of their emperor and to be taken away to Moravia or Hungary. I don’t know if they ever received it, but we never got a response. A few days later we heard that the Crown Prince of Sweden had arrived and I remembered that I knew his aide-de-camp, Noailles. We wrote to him and were overjoyed when he came to visit us, staying to chat. I put to him my idea of again writing to the Austrians; I knew too much about the Prussians to want to fall prisoner into their hands and the idea of being sent deep into Russia filled me with horror.

Transfer To Sweden Seen As Only Option

Noailles suggested I join a convoy of prisoners that the Crown Prince was sending to Sweden; I was reluctant as I felt I was still too weak but was persuaded in the end as it seemed my only option. I was added to the list and later joined the convoy, which, twenty days after the battle, set off for Stralsund and captivity.

Saint-Chamans was perhaps fortunate because he was an officer of some standing. Life in Allied hands after Leipzig for the majority of French prisoners, the rank and file, was much worse, especially for the wounded. A Leipzig postmaster noted in his journal the condition of the unfortunate French prisoners he came across after the battle:

In view of the great shortages absolutely nothing could be given to the many thousands of French prisoners. These were left to their fate and had to go hungry. In the early days, as I saw for myself, they devoured horseflesh and hunted out and swallowed half-rotten cabbage-leaves and stalks on the rubbish dump. All sorts of raw waste was thrown out from the kitchens, and they fought over this. Horses killed in the battle lay in groups all over the town and in the suburbs, because people had more than enough to do to bury the dead and could not think about horses yet. So long as the French could get it, they fed off horseflesh, mostly raw because they had no wood to light fires. When they ran out of this meat they fell upon their dead comrades. Human suffering had reached its peak. Yet however these sons of the great nation had behaved in the past, it was heartbreaking to have to watch their misery.

A Disillusioned Saint-Chamans Returns To France

And so the French lost Germany, Saint-Chamans lost his freedom, and Napoleon lost the biggest battle of his career. Saint-Chamans later returned to France but, disillusioned by Napoleon’s ambition, he did not support the emperor in 1815.

Colonel Saint-Chamans’ memoirs, touching upon the trials and tribulations of a Napoleonic officer, throw light on the great campaigns from the point of view of a French light cavalryman. They are a valuable corrective to the type of memoir produced by Marbot and Parquin, and underline the fact that for the majority of Napoleonic officers the wars were strife and suffering rather than episodes of glorious exploit. For the common soldiers, like those abandoned in Leipzig or any other battle, who did not leave a written record of their ordeals and adventures, life on campaign and in battle was considerably worse. Their story is rarely told.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments