By Gerald Astor

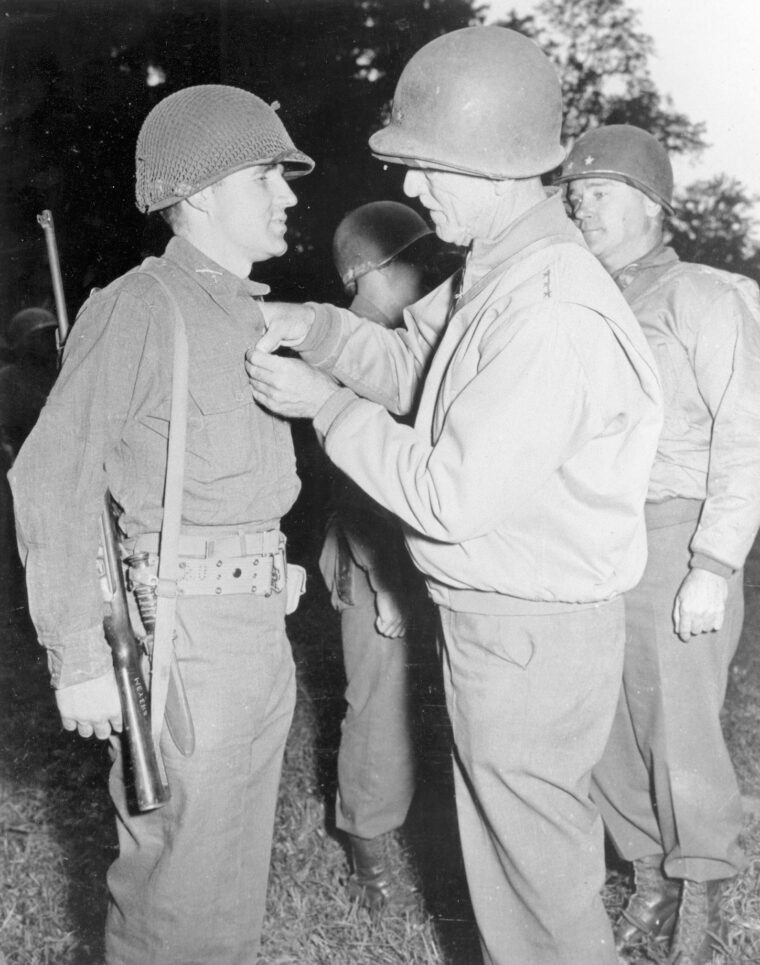

As a captain during World War II, George Mabry, with the 4th Infantry Division, slogged ashore on Utah Beach on D-Day and led troops through the Normandy Campaign. As a major he fought the bitter battle of the Huertgen Forest, and as a lieutenant colonel survived the Battle of the Bulge and eventually directed GIs into the heart of Germany. For valor in combat, Mabry earned a Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Service Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster, Legion of Merit with two Oak Leaf Clusters, Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, plus other decorations. Only Audie Murphy may have collected more awards.

South Carolina bred and raised, Mabry graduated from Presbyterian College in 1940, where he completed a Reserve Officers Training Corps course. Although he had a contract to play minor league baseball and to teach high school, he reported to Fort Benning, Ga., and the Regular Army’s 4th Infantry Division as a platoon leader in the 8th Infantry Regiment. “[Company Commander] Carl Duffner was 6’2”, Major Bull Holland, the battalion CO, stood 6’4”, said Mabry. “Every individual of authority whom I encountered was big and tall. I was short of stature, 5 feet, 71/4 inches, but I don’t think I had a little man’s complex. Yet, I was always aware that the big man has an advantage. I remember from football, coaches would look at a big man and ask, ‘What position do you play?’ When they came to a little man like me they would say, ‘Whatchu out here for, boy?’ All my life I was an athlete. I’ve always felt I had to put out more than a big man, particularly in athletics. In a leadership position, particularly when dealing with troops, when you issue them an order you better be prepared to do exactly what you expect of them. Never ask anyone to do anything that you would not willingly do yourself.”

Utah Beach on D-Day

On June 6, 1944, before the gray dawn off the French coast, Mabry and a naval officer coordinated the loading of boat teams from a troop ship onto landing craft. The assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., had chosen to accompany Mabry’s battalion. When it was nearly time for his boat team to load, Mabry hastened to notify Roosevelt. “He thanked me,” said Mabry, “and then hollered to his aide, ‘Stevie, where is my lifebelt?’ Stevie said, ‘General, I don’t know. I’ve already given you three.’ General Roosevelt said, ‘Dammit, I don’t care how many you’ve given me, I don’t have one now.’” Mabry and the aide searched and found one for the general. When Mabry asked whether Roosevelt had all his armament, he patted his shoulder holster and responded, “I’ve got my pistol, one clip of ammunition and my walking cane. That’s all I expect to need.”

Compared to Omaha Beach, the other site chosen for American landings, Utah, was less heavily defended. Two casemated positions overlooked the shoreline, but only one actually held big guns. The Germans had not completed installation of barriers in the water, and there were fewer mines. Underwater demolition teams blew up much of what posed a threat to landing craft. Furthermore, the naval bombardment, in contrast to what happened off Omaha, pounded the shoreline, punishing the existing German positions and also providing convenient shell holes in which foot soldiers could take refuge.

Mabry, with his battalion commander, Lt. Col. Carleton McNeely, occupied a “free boat,” one that could come in at any stage of the invasion. McNeely decided to arrive behind the third wave when some idea of the progress of the assault could be determined. “As light began to improve,” said Mabry, “the first casualty I saw was a Navy boat which apparently had hit a mine. One sailor was lying on the keel of the boat, holding onto a man who was obviously either critically wounded or dead. That boat had been stationed to mark the lanes for approaching the beach. Soon after, I saw a large transport hit a mine.

“About this time, the bombers began to bomb the beaches. Smoke and dust obliterated the area. We couldn’t see the shore or any distinguishing features which we had memorized. As the bombers went away, naval gunfire opened up. They began to pulverize the beaches and behind them.

“The coxswain, a Navy man piloting our craft, kept falling back farther and farther behind. Colonel McNeely hollered for him to speed it up, and then we slowed down. About this time we passed some of the floating tanks from the 70th Tank Battalion which had worked closely with the 8th Infantry in England. They’d been discharged 800 or 900 yards from the beach. Unfortunately, they didn’t work too well in the rough Channel. They had a rubber raft, and you’d see the crew take it out and jump on it and get away.

“When, for the third time, Colonel McNeely told this coxswain to speed it up and we slowed down again, McNeely pulled his pistol and pressed the barrel against the sailor’s head. The young fellow understood. He really moved out. We went through the third wave, traveling fast. I was trying to pick up landmarks; the bombing apparently knocked them down but we figured there was something wrong. The terrain, the beach didn’t look right. We could see the mouth of the Merderet River, and we were supposed to be a thousand yards farther to the right.

“As we approached the beaches the pillboxes became more clear. The tetrahedrons (steel emplacements designed to thwart landing craft) stood out like bristles on a hog’s back. We landed right behind the second wave, elements of E and F Company. Just as the bottom of the landing craft touched the ground, this coxswain dropped the ramp. He wasn’t going any farther. Men began to jump off the left and right corners of the ramp. We’d been trained that once you hit the beach, you run across that thing; never lie down on it and don’t crowd up against the seawall. You’ve got to push on inland. That was drilled into us.

“I moved forward. Ahead of me was a man carrying [something] like a cloverleaf of 81mm mortar ammunition, which he was to drop at the seawall so that H Company with the mortars would then run down to the seawall and gather up the ammunition for their use. A mortar round came in and hit this soldier right on top of his head. That caused the 81mm mortar rounds to detonate also, and this man’s body completely disappeared. I felt something hit me on my thigh, and it was this man’s thumb. It was the only discernible part of a human being you could see. To my left I saw a human stomach lying on the beach. It was a stark, grotesque sight.”

Navigating The Minefield and Further Inland

Mabry knew for certain that they had come ashore to the left of their original proposed site because of the location of the Merderet. He spotted Roosevelt, waving his cane, urging troops to keep moving. The assistant division commander, who had preceded Mabry to Utah, having recognized the deviation from the planned landing area but realizing the relatively light opposition, had immediately directed the GIs to head inland.

Although separated from other troops, Mabry now sought to implement the plan devised with McNeely. The strategy called for troops to proceed over sand dunes about a half mile to an inundated area. There, three causeways crossed the flooded low ground. Seizure of these was vital to inland movement by the Americans because they crossed a wide area of virtually impassable swampland. Mabry and McNeely divided supervision of their attacking companies.

“I followed a squad of about six men from G Company being led by a red-haired sergeant,” recalled Mabry. “As they went over the seawall, they began moving toward a fence. The sergeant started through the barbed wire. A tremendous explosion occurred. Obviously, he had stepped on a mine. All six men fell to the ground, some killed, some wounded, some screaming. I ran beyond them because my mission was to follow G Company and ensure that Causeway One was secured. Naval gunfire was now falling inland, and German artillery was coming in the area where we were located.

“I was by myself and didn’t see anyone else. I began to run over a sand dune and started to receive small-arms fire from some Germans dug in on the sand dune line. Periodically, I would hit the ground and try to survey the situation and pick up the smoke from the German rifles to locate them. After about two short rushes from one sand dune to another, I looked around and noted I was in a minefield. The wind had blown away the sand and uncovered some of them. Having seen the squad killed and wounded by the mine, I thought if I turn around and try to go back to the beach I’ll probably step on a mine. My mission is inland, so I’m going to take my chances and continue to move toward the enemy firing at me.

“I got up, made another dash, landed successfully and safely. The next time I jumped up and ran, the small-arms fire was cracking around me pretty close. I made a long leap to a shell hole I had espied, and while in mid-air my right foot apparently caught the tripwire attached to a mine. The mine exploded, and the force of it slammed me against the shell hole. It numbed my right leg, and I thought I had lost a foot. Looking around carefully, I found I had not been touched. My leg was intact. I regained my composure and decided to continue the advance.

“A Vast Panorama Lay Before Me”

“By this time, the German rifle fire had subsided a little bit. I assume they thought I had been killed by the mine explosion. I jumped up and ran directly toward the position the Germans were firing from. Apparently, I startled them. When I reached the top of the dune line, I saw several individual foxholes. The first one was empty, but hand grenades and rifle ammunition was all around the edge. I jumped into it and quickly realized this was a rather precarious position because they must have seen me. I scrambled out and saw, about eight yards from me, a German in a foxhole who had a hand grenade, a potato masher. I wheeled and shot him in the throat. Germans started getting up on all sides of me; the total count was nine. They raised their hands quickly. After corralling the Germans in a group, I glanced over my shoulder. Through a gap in the dunes, a vast panorama lay before me. It was an incredible mass of ships, all sizes, that choked the Channel as far as the eye could see. I understood why the Germans had surrendered so easily.”

After sending the prisoners toward the beach under guard, Mabry then searched for G Company. About 300 yards farther inland, he met a pair of GIs, including a BAR man named Ballard whom he knew to be an excellent marksman. They came upon a huge German pillbox. “Machine-gun fire opened up on us, and we dove into a deep ditch nearby. We crawled down the ditch until within 150 yards of the bunker. I told Ballard to spray the slits of the bunker with his BAR to determine whether these Germans inside really meant business. He gave a few well-placed bursts and ducked down in the ditch. Two embrasures of the pillbox began delivering machine-gun fire over our heads. This was a formidable emplacement, and they meant business. I asked the other soldier if he knew the route back to the beach and could bring back one of the DD tanks and other soldiers.”

The first DD tanks had finally crawled ashore. About 30 minutes later, Mabry’s emissary led two of them forward, and they began to blast the pillbox. After one tank maneuvered forward and stuck its gun muzzle directly into one of the bunker embrasures, the inhabitants poked out a white flag. Mabry and Ballard counted 36 Germans who surrendered. Other barriers fell under the onslaught of the tanks. A flamethrower drove 25 defenders from another pillbox, as well as two American paratroopers being held prisoner. Mabry, having dispatched BAR man Ballard to escort the prisoners to the beach, grabbed another GI to accompany him toward Causeway One. They reached a point where Mabry noticed a hedgerow, which he believed put them close to the objective. However, a field surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, which frequently indicated a minefield, lay dead ahead.

“I crawled through the wire fence and into the field. Talk about walking on eggshells, I was really tiptoeing. I detected no bumps in the ground and saw no disturbances of the earth, either fresh or old.” The minefield was a fake. Mabry continued, “I motioned for the soldier to follow. We quickly reached the hedgerow and, keeping low, began to creep down it. I peered over the top, and there, only 150 yards away, I saw our Causeway One. At this time we began to hear rifle fire coming from across the flooded area opposite the causeway bridge.

“When we reached a point only 45 yards from the causeway, we were forced to stop. I decided to make a dash for it and told the soldier to cover me. If I did not get pinned down, I would wave him across. I made it to the ditch, which was filled with nearly two feet of water. I had received no fire, so the soldier promptly followed me. I noticed then that the rifle fire had begun to pick up on the far side of the bridge. We had moved up to a position just 30 yards from the causeway when three German soldiers began running down the road. I told my companion not to shoot until they got very close to the bridge. When they reached within 10 yards of the far side, we opened up. All three men fell. Immediately, a squad of seven or eight Germans appeared and moved off the road to their right. They approached the bridge in skirmish formation. They were clearly trying to outflank us, and we began shooting at them.

“The gunfire on the far side of the bridge intensified. I felt some of the shots were directed at the same Germans we had engaged. Some of the firing, however, seemed to be aimed at us and had the sound of an M-1 rifle instead of a German one. I believed American paratroopers must be closing in from the other side of the bridge. I pulled out my square of orange cloth, which identified us as allies, and hoisted it on a stick. A few more rifle bullets cracked around, but then an orange flag waved back and forth from beyond the bridge. It had to be the paratroopers. All the rifle fire concentrated on that squad attempting to outflank us.”

Driving a Wedge Into German Resistance Outside Eccausseville

Mabry then attempted to run across the bridge to make contact with the paratroopers. Eight Germans threw up their hands in surrender. “An airborne soldier jumped over a hedgerow with his rifle at the ready,” Mabry continued. “I hollered to him, ‘Don’t shoot, I got some prisoners.’ I marched them up to him, and he was a member of the 101st Airborne Division.” Three days later, Mabry’s battalion drove a wedge into the German main line of resistance near Eccausseville. The penetration exposed the troops to a scythe of machine-gun fire and a rain of artillery. Mabry crawled back toward the battalion command post to report the crisis and arrange for reinforcements. He braved barrages of shells and sweeps by the machine gunners to reach the CP. He then headed to the front, leading the reinforcements. He personally participated in a successful attack, which featured hand-to-hand combat. For his heroism from June 6-9, Mabry was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross.

At a road junction before the next major objective, Cherbourg, the GIs were pinned down by both intense small-arms fire and a German 88mm gun. Mabry organized a fire and maneuver approach. At considerable cost in dead and wounded, the 4th Division soldiers advanced. Mabry was with the final assault group that stormed the enemy strongpoint. A Silver Star recognized his valor.

Several weeks later, the Eighth Regiment joined a campaign to breach the West Wall or Siegfried Line, a thick series of fortifications that guarded the German border. From their emplacements, the Germans leveled murderous fire at the Americans. Now a major, Mabry led a small patrol to find the hot spot. Undetected, he sifted through the trees and underbrush until he could see the pair of machine guns and their crews that were exacting such a heavy toll. Sending his companions back to a safe position, the major raised the 29th Field Artillery on his radio and called in the coordinates. The first rounds burst uncomfortably close to him, but he stuck it out, adjusting the big guns until they smashed the target. A Bronze Star followed.

Outside Huertgen Forest

By mid-November 1944, the battalion was part of an ill-fated, poorly conceived plan to strike through the thick-treed, heavily mined, massively fortified Huertgen Forest. As November 16 dawned, air support pounded the area along the forest front with tons of deadly ordnance. James Haley, a staff officer of Mabry’s 2nd battalion, remarked, “The enemy positions close in front of the 4th Infantry Division went untouched [because] no bomb line close in could be clearly defined.” The artillery that followed the aircraft, however, struck much nearer. “The shells could be heard whining overhead and crashing into the trees, showering the area with fragments. The forest was literally being chewed to pieces by the exploding shells. Trees fell across each other, making large areas absolutely impenetrable. However, as it was soon to be evident, the Germans were so well dug in that they suffered only slight casualties.”

A South Carolinian and Clemson graduate, Captain John Swearingen was the battalion S-3, or operations officer. He said, “We moved out, proceeding approximately 1,000 yards without opposition until all hell broke loose. The Germans had prepared and occupied a massive defensive position. They had concertina wire stacked three high, two on the ground and one on top. The enemy machine guns were spaced every 50 feet with fields of fire placed between trees. In front of the wire were mines, almost solid, with mortars zeroed in front of them.” Still, by stretching the interval between men slogging over a muddy road to conserve strength rather than attempting to cross rough but more concealing terrain, the forward part of the column reached positions that put them close enough for a final assault. Out of necessity, the friendly artillery and mortars shifted their attention. No longer forced to seek cover, the enemy drenched the GIs with devastating fire from a variety of weapons. The Americans doggedly pressed their case, gaining perhaps 200 yards before a barbed-wire entanglement higher than a man’s head spanned the entire front. Schu mines blew off the feet of the first to who ventured close to the triple layer of concertina snarls. The Germans, hidden from sight, could target every man from E and F companies leading the assault.

“It also became evident,” said Haley, “that E and F companies were caught in an area on which the Germans had previously registered their artillery and mortars. In spite of all efforts, the advance was halted, and E and F companies were pinned to the ground by deadly machine-gun fire from the front and flanks. Friendly artillery and mortar fire was brought in as close as possible, but still the enemy fire continued. By this time [the enemy fire] had reached a crescendo. Experienced officers, who had fought all through Normandy and across France, later stated that they had never before seen the Germans mass so much artillery fire on one area.”

A Plan Doomed to Failure

At the hillside battalion headquarters, 400 yards behind the killing field, the long-range weapons of the Germans blasted the slope, putting in peril any individual not in a bunker. Lieutenant Colonel Langdon A. Jackson, Jr., the battalion commander, talked to Colonel Richard McKee, the regimental CO, by field telephone, explained the dire situation and advised that his people had been so hard hit they could not advance. McKee ordered him to renew the effort. Jackson summoned the G Company commander to the CP for instructions to commit his unit.

As he made his way toward Jackson, his opposite number at F Company also worked his way back in order to give a firsthand report. Before either reached the destination, a concentration of artillery shells seriously wounded both. The commander of E Company had already been killed. The insertion of G Company only added more dead and wounded without a breakthrough.

As night fell, Jackson could only direct the survivors to withdraw under the mask of darkness and dig in at the original line of departure. The battalion commander spoke again to his regimental leader, reporting the loss of all rifle company commanders and most of the platoon leaders and noncoms. He requested his battalion be taken off the line. McKee not only refused but also ordered the shaken survivors to attack in the morning. According to Swearingen, who overheard one side of the conversation, McKee apparently accused Jackson and his men of being “yellow.” Jackson replied, “I am not yellow, and neither are my men.”

Haley said, “The battalion plan of attack for 17 November was essentially the same as that for the previous day, and for this reason was doomed to failure before it began. E and F companies were again to attack abreast in this area in which they had been slaughtered the day before.” The only two changes were more bangalore torpedoes to cope with the barbed wire and the assignment of tanks to smash a pathway through the minefield and breach the barbed wire. The noise of the armor clambering up the trail alerted the Germans, who scoured the area with artillery and mortar fire while the foot soldiers burrowed deeper into their foxholes as they awaited the hour of the assault.

At 0900, zero hour, the GIs obediently left their positions only to discover that just one tank out of five originally deployed had made it to the line of departure. Mud and the steep slope halted the others. The single tank gallantly led, breaking a path through the mines, but could not penetrate the wire even though it slammed into the obstruction several times. Again, the GIs cowered on the ground, unable to move without being picked off and vulnerable to the rain of shells.

Jackson again pleaded with McKee for relief. Instead, he was ordered to hold his present position and prepare for a third assault on 18 November. Jackson replied that such a venture was impossible in light of the condition of his forces. Regiment finally agreed to replace the 2nd Battalion with the 3rd for the next round.

Jackson then repaired to regimental headquarters to confer with McKee. After the war, George Mabry told his son, Benjamin, that when ordered to attack a third time, Jackson “quit.” He followed the telephone wires back to the rear and was relieved of his post. Mabry assumed command of the battalion with Haley as his exec.

Taking Out Mines With a Trench Knife

Mabry said he was chagrined to hear McKee announce that he would write off the 2nd Battalion and offered to reorganize the outfit and mount another attack. McKee allowed Mabry a day to prepare his new command for its role. About 200 replacements checked in to fill the depleted ranks, but even with these additions the 2nd Battalion mustered only about 60 percent of its full complement and the line companies carried only an average of two officers.

As the disintegrated 2nd Battalion assembled in the village of Bend, Mabry scrounged for officers and noncoms, even cajoling a victim of battle fatigue to leave a rear echelon post and return to the front. On the morning of November 19, the reborn 2nd Battalion started out from Bend. In hope of surprising the defenders, the American artillery remained silent. The strategists believed the Germans might be focused on the effort by the 3rd Battalion on the left flank of the 2nd. As the troops climbed a steep ravine, a machine gun on a nearby hill locked on them, and any attempt to evade the withering fire drove the GIs into one of the ubiquitous minefields. The scouts and others leading the battalion sought cover and refused to advance. Mabry, who with his staff had been following in the footsteps of the lead company, moved to the head of the column.

Arriving at the mine-seeded turf, Mabry conducted a hasty personal reconnaissance and then directed his people to detour around the hill and its machine-gun emplacement, rather than going through the infestation of schus mines and up the slope. Members of the battalion succeeded in bypassing these obstacles only to encounter an even more extensive minefield. Several soldiers went down, and an aid man who started toward the wounded incurred serious injury.

Years later, Mabry said he needed to figure a way to clear a path in the minefield. Studying the snow-covered ground he noticed indentations in specific places, which he reasoned indicated the presence of mines. On his own, using his trench knife, the battalion commander crawled forward and dug out the devices to clear a safe route. Beyond the mined zone lay enemy bunkers. Mabry personally led the soldiers, with several scouts trailing him. He approached the first emplacement and kicked open the door, but it was deserted. He proceeded to a second dugout and again smashed through the entrance. Nine German soldiers charged him. He knocked down the first with his rifle butt and bayoneted the second. The GIs behind him subdued the remainder.

The small party of Americans with their battalion commander in the lead then rushed a third bunker despite its vigorous small-arms fire. These inhabitants also surrendered. The American forces under Mabry now rallied sufficiently to fight their way to a small stream. When the forward platoons crossed to the opposite bank, the Germans from above rolled grenades down toward them. It was now late in the day, and Mabry halted the attack. For this day’s work, he received his Medal of Honor.

Entering the Battle of the Bulge

By mid-December, the 4th Division, exhausted by the Huertgen campaign according to Mabry, occupied a “quiet section of Luxembourg to regroup and lick our wounds. My battalion had been reduced in strength to a point where my companies consisted of not more than 40 men each.” In this weakened state, the battalion had been designated as the reserve for the division.

Mabry was engaged in retraining his men with anticipation of an infusion of replacements on December 17. The day’s exercise involved convoy march discipline. For this practice, the GIs had loaded aboard trucks when Mabry received an order to report to headquarters. In a jeep with a driver and radio operator, he drove to the division CP to see General Raymond O. Barton, the division commander.

“He was pacing the floor, chain smoking and appeared quite disturbed. He asked me if I knew what was going on. I said, ‘No, sir.’ Barton then explained that the Germans had launched a major counterattack and were pouring through the division’s position, which was spread over a 30-mile sector. He did not know where the Germans were or in what force. He had lost contact with many elements of the division.”

Unbeknownst to Mabry, the German Army had surprised the thin American defenses in the area known as the Ardennes Forest and launched the attack that developed into the Battle of the Bulge. “He took me to a map, put his arm around my shoulders and made the following points. My battalion was the only reserve the division had. He was rounding up every available man at headquarters, including cooks and bakers, to constitute a division reserve after he committed my battalion. He then issued the shortest oral order I ever received, in words to the effect, ‘Proceed up this main road [pointing on the map] until you hit the enemy, then attack. Once you’ve done that I’ll try to get these cooks and bakers up to you if possible. There will be no one to your right or left. You got that?’ ‘Yes sir,’ I replied.”

Mabry informed Barton that because his men were already on trucks the maneuver could begin immediately. By radio, Mabry told Haley to get the show on the road and said he would catch up along the way. “After traveling only a couple of miles, we began encountering hundreds of civilians, streaming towards Luxembourg,” recalled Mabry. “When asked if they had seen any Germans, they would only point to their rear and keep moving.”

The jeep journey of perhaps 30 miles abruptly entered a quiet zone. The civilians vanished, and the paved road suddenly veered sharply to run along the crest of a high ridge. “As we proceeded,” said Mabry, “we came under heavy and accurate fire from assault guns and artillery. I told the driver to floor-board it. We ran the gauntlet until we could whip off the road into a field behind a small hill. The problem was how to get back on the road beyond the ridge and stop the battalion before it could be decimated by the German fire. It took quite a while to work the jeep cross country and to the road, but at a point about 100 yards from the road I spied the battalion, guide-ons flying. I was able to turn the trucks off short of the ridge. As the soldiers dismounted, I walked along with each company commander and issued an oral, fragmentary order, basically to attack in a column of companies to seize a dominant hill mass that overlooked a ‘Y’ of two paved roads leading to a main highway into Luxembourg.”

“Proceed to Luxembourg At All Costs”

The vigorous assault by the Americans initially captured the military crest of the objective and established control over traffic into the road junction. The enemy responded with four daylight attacks during the following week. For three days, the besieged battalion lost touch with its artillery support. The narrow area of the intersection accommodated only one tank at a time. Mabry’s troops held off tanks by mining the area. Twice the Germans tried to swarm up the hill after dark. “It was so steep,” said Mabry, “we could hear them climbing up toward us. They would get within 15 to 20 yards of our position before we opened up with everything we had.

“One day, a lieutenant on patrol killed three Germans to our rear. This reassured me that the Germans were freely patrolling to our rear and knew we were isolated. The next day, another patrol ambushed some Germans, killing four and capturing a lieutenant colonel who had a written order. I believe it was issued by an army group or division and directed German units to our front to launch an attack two days from that date and ‘destroy all enemy to their front and proceed to Luxembourg at all costs.’”

The official Army history of the Ardennes campaign said the order indicated no prisoners would be taken and any Americans who surrendered would be killed. Mabry later insisted there was no statement to that effect, other than the words, “destroy all enemy….” In fact, he noted that on one occasion some 200 civilians suddenly appeared moving down one prong of the ‘Y’ in the midst of a brisk exchange of small-arms and mortar fire. He ordered a temporary cease-fire, and the Germans also paused to enable the refugees to flee toward Luxembourg.

The German field order specified a time for an attack two days later. Mabry plotted a preemptive strike to throw them off balance. Under cover of night, he pulled back one front-line company and merged it with his reserves. His other front-line company spread out to occupy some of the abandoned foxholes. At 0330 two companies crossed one fork of the road and began a limited attack. From the heights, the remaining GIs poured down supportive fire. The Americans in the assault force advanced, then pulled back bearing their dead and wounded.

“It worked like a charm,” bragged Mabry. “To a couple of Germans we captured later, [it seemed] we had been reinforced and now were up to at least regimental strength.

A Close Call at the Rhine

“The following morning, when the Germans were supposed to attack at 0530 and destroy us, I requested our division artillery to give us a ‘time on target’ [a coordinated barrage with all shells adjusted to hit and explode simultaneously] at 0500. In addition, we had hand carried 81mm mortar ammo all night long. At 0500 all hell broke loose when we opened up with every available weapon. Later, three captured Germans said we had decimated them because they were caught out of their foxholes. At about 0900 we did get an attack supported by tanks, but it had no punch.”

The stonewalling of the 4th Division’s 2nd Battalion was a key component of the defense during the Battle of the Bulge. General Barton was prepared to nominate Mabry for a Medal of Honor, but when he heard his battalion commander was already recommended for the award he assumed it was for the action in the Ardennes, rather than the Huertgen Forest. He withdrew his commendation, and Mabry actually went unrewarded for the Battle of the Bulge combat.

On one occasion, Mabry was also forced to deal with a war crime committed by Americans. Several times, the troops became aware of mistreatment of American wounded or captives by the enemy. A junior officer, a graduate of West Point, retaliated, executing some prisoners. Mabry broke him on the spot and lectured his people, “You fight like hell during the battle. But when it’s over your enemy is due the privileges of a prisoner, just as you are. I will not countenance the murder of a POW and will immediately relieve any other officer I suspect of carrying it out.”

Subsequently, Mabry’s luck almost ran out. After the shattered units of the 4th Infantry had been taken out of the line and infantry replacements, fresh from the U.S., filled the thinned ranks, the division was approaching the Rhine River. A piece of shrapnel nicked him, bringing the Purple Heart.

Having opted for the Army as a career, Mabry progressed through the ranks while attending the schools required for advancement. He drew command assignments in the Panama Canal Zone and Korea (after the war there), and as a general assumed command of the 1st Armored Division in 1965-1966.

He first visited Vietnam in 1966, as a member of a 100-person team of civilians and military men, to evaluate the American involvement. After holding several more posts, he returned to Vietnam as chief of staff and assistant deputy commanding general of the U.S. Army forces under General Creighton Abrams. Mabry, as an old-line stickler for military discipline and protocol, had become uncomfortable with the free-wheeling, clandestine operations of the Green Berets working with the CIA. When he learned that a Vietnamese citizen suspected of being a double agent had apparently been executed by the Green Berets and of threats to an American witness, Mabry instigated a court martial proceeding for those involved. The case ignited a controversy. Played out against the backdrop of the antiwar movement in the United States, the matter threatened the continuation of U.S. participation in the conflict. At the highest level, a decision was made to shut down the court-martial on the grounds of national security.

The resolution could not have sat well with Mabry. He had been pushing for a full review of what had occurred. The one-time college athlete still wanted to play fair. He retired from the service in 1975 and died in 1990.

I had no idea of Gen.Mabry….despite living in/nearby Camp Mabry. Glad to have read this.