By Eric Niderost

Morris “Moe” Berg was a man of many talents: linguist, lawyer, baseball player, spy. Although this Renaissance man gained a modicum of celebrity on the baseball diamond, Berg is best remembered as an operative for the OSS (Office of Strategic Services), a World War II forerunner of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

The world of espionage is of necessity a shadowy one, and in Berg’s case the term “government spook” is particularly apt. He was truly a phantom, a man so secretive much of his personality remains a mystery. Moe Berg was a man of glaring contradictions. He seemed to love the rough-and-tumble camaraderie of the baseball diamond, yet rarely socialized with any of his teammates. He was also a man who played in the major leagues for over a decade, yet warmed the bench throughout much of his career. A loner and eccentric, he was an intensely private man in a public profession.

A Charming Man With Few Friends

Morris Berg was born on East 121st Street in Manhattan on March 2, 1902, the son of Russian Jewish immigrant parents. The Bergs were not practicing Jews, but young Moe was proud of his heritage and learned to speak Hebrew. It was the beginning of a lifelong fascination with languages. During the course of his life, he became fluent in French, Spanish, and Portuguese, and was fairly competent in Italian, German, and Japanese. The latter tongues, of course, would prove invaluable to an OSS agent. Berg was also familiar with Hebrew, Yiddish, Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin. As a college ballplayer at Princeton, he confounded rival teams by communicating on the field in Latin.

Berg had many acquaintances but few, if any, true friends. He was a charming man, but there was a private inner core that he refused to reveal, and people sensed this. Perhaps this sense of isolation was fostered in his years at Princeton University. In the early 1920s, Princeton was a bastion of privilege, where an obsession with pedigree brought a tincture of anti-Semitism. Berg was a gifted, even brilliant, student, graduating cum laude in 1924 with a degree in modern languages. His Jewishness set him apart, a fact underscored by such transparent snubs as his failure to be voted Phi Beta Kappa.

Baseball was the great love of Berg’s life, and he chalked up an impressive record as a college shortstop. It was enough to attract the attention of Wilbert Robinson of the Brooklyn Robins (later Dodgers). Robinson knew Brooklyn had a large Jewish population and figured Berg would sell more tickets. The young man eagerly signed the contract over the objections of his father. Moe was undeterred by parental concerns; he genuinely wanted to play, and the $5,000 he was given once the ink was dry was an added inducement.

The rookie player used the money for a trip to Paris. Paris was an exciting place in the 1920s, a cultural mecca well described by Ernest Hemingway as a “movable feast.” It was a feast indeed to young Berg, who reveled in its cosmopolitan sophistication. He even attended the Sorbonne, not the usual course of action for a rookie American ballplayer.

“He Can Speak Several Languages, But He Can’t Hit In Any Of Them”

Berg came home a seasoned traveler, but his performance on the baseball diamond was anything but auspicious. In fact, he was soon traded to minor-league teams, but this “exile” lasted only two years. By 1926 Berg was with the White Sox, a major-league franchise trying to forget its scandal-laced past.

Moe was an enigma even on the playing field. He unquestionably had talent, and there were times when he would rise to the occasion. While still in the minors, Berg hit two home runs and a double in a single game, but his lifetime batting average was .243. It was said of Berg, “He can speak several languages, but he can’t hit in any of them.” A teammate once opined, “Moe, I don’t care how many of them college degrees you got, they ain’t learned you to hit that curve ball no better than the rest of us.”

The nongrammatical quote underscores what an oddity Berg was in the baseball of the period. Not that the game lacked college men; Lou Gehrig went to Columbia, for example. But teams were largely populated by farm boys or working-class urbanites not known for high intellectual pretensions. It was a telling contrast when Berg might be seen in the dugout reading philosophy while a neighboring teammate scanned a comic book.

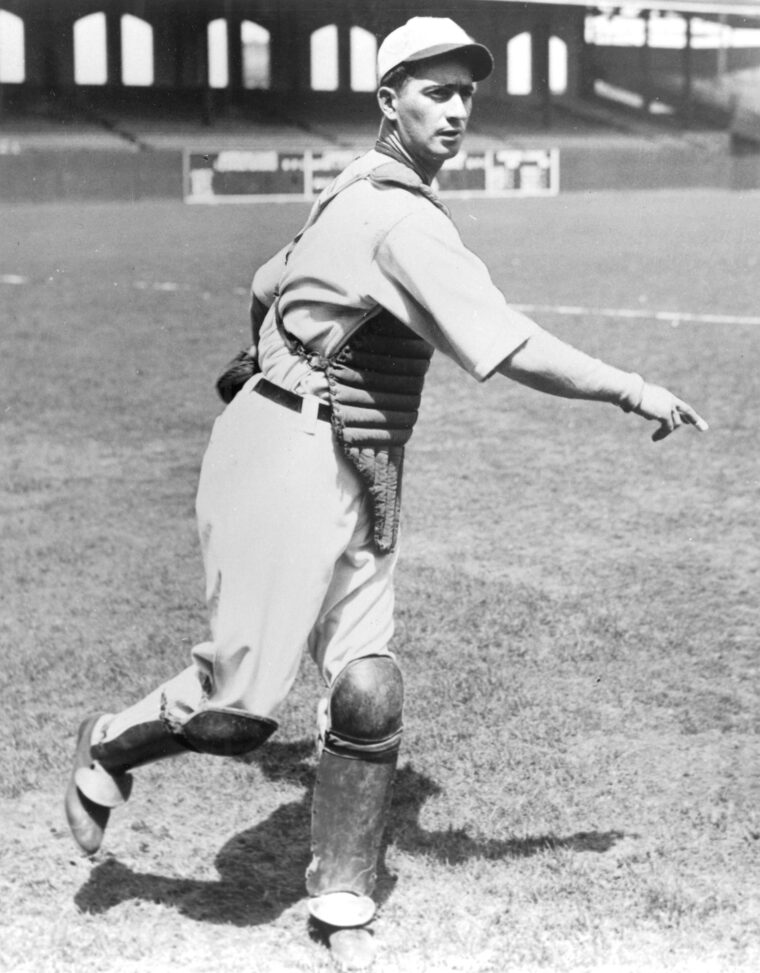

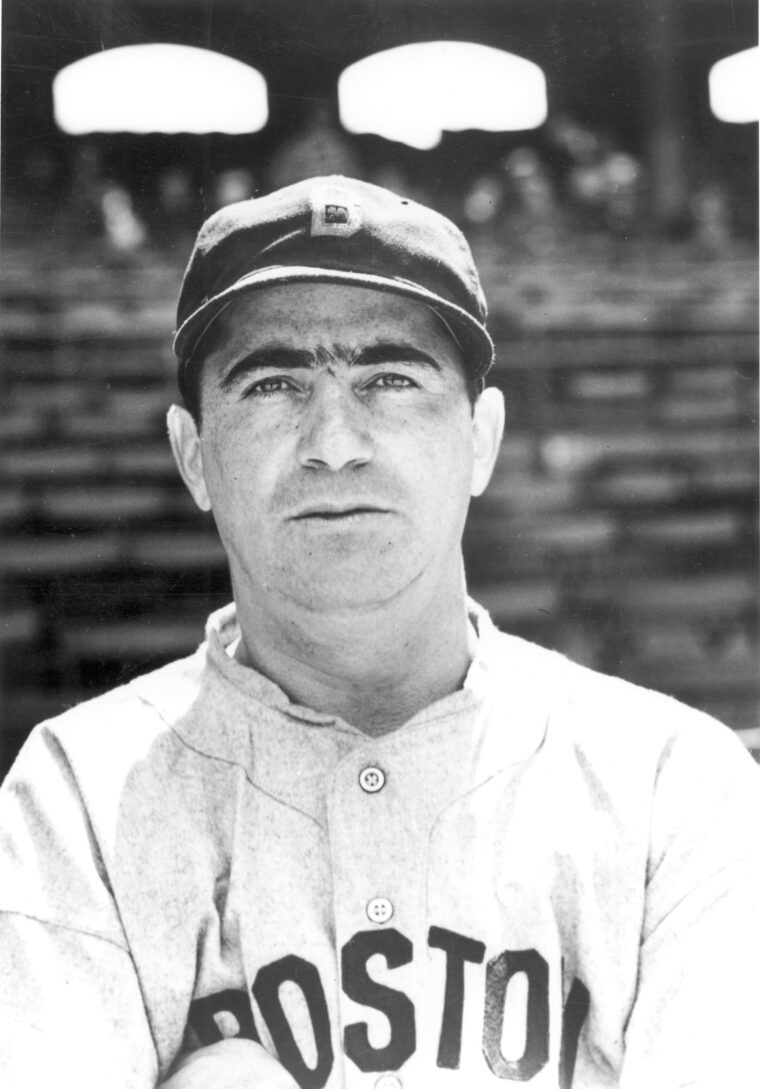

In 1929 Moe Berg reached the pinnacle of his career as a first-string regular catcher for the White Sox. He had a quick intelligence, a good eye, and a “rifle” arm, and seemed well on the road to Hall of Fame greatness. The next year he sustained an ankle injury that sidelined him for weeks. Professional baseball can be an unforgiving sport, and Berg was now “damaged goods.” He would still play occasionally, but generally spent the rest of his career as a third-string catcher for a succession of teams, including the Washington Senators and the Boston Red Sox. Most of the time he warmed the bench, holding court as “Professor Moe,” the intellectual ballplayer.

Baseball Seminars in Japan

In 1932, Berg accompanied Lefty O’Doul and Ted Lyons to Japan to conduct baseball seminars. The trip appealed to Berg’s restless spirit and wanderlust, and it afforded him an opportunity to study a new culture and learn a new language. Here was another movable feast—but with an Asian accent. Berg’s intellectual curiosity was stimulated by the sights, sounds, and even smells around him. Despite reports to the contrary, Berg was never fluent in Japanese, though he knew enough to hold simple conversations. His blend of baseball and education also made him a hit with the Japanese.

In 1934, Berg visited Japan again, this time with an All Star team that included such legendary players as George Herman “Babe” Ruth and Lou Gehrig. In retrospect, Berg’s inclusion seems odd, fueling speculation on the “real” reasons for his return visit. What was Berg, who rarely left the bench and never played in a World Series, doing in the company of baseball immortals? Was Berg a U.S. intelligence agent even then? Was his inclusion on the All Star team an elaborate “cover” for clandestine operations?

Certainly Berg’s recorded observations on Japan never go beyond the “exotic East” tourist level. Japan in 1934 was a society dominated by the military. Bushido, the “way of the warrior,” was exalted, but all Berg seemed to see were quaint teahouses, kimonos, and geisha girls. Japan needed raw materials for its economy; the island nation was not self-sufficient. Military conquest seemed a viable option, especially since a virulent Japanese nationalism held most of its Asian neighbors in contempt.

Playing the Tourist in the Tsukiji District

In 1931, Japan seized Manchuria from China’s enfeebled grasp; soon China itself would be the target of Japanese aggression. The United States and Europe were preoccupied with the ravages of the Depression; protests were lodged, but little else was done. By the mid-1930s, Japan became a pariah nation, increasingly sensitive about negative world opinion. The Japanese, feeling their isolation, became paranoid about “foreign spies,” agents who were said to lurk everywhere.

Moe Berg seemed oblivious to Japanese concerns—in fact, he even brought a movie camera to Japan with him. Given the political climate, this was an act of almost suicidal bravado. Ostensibly, he was picking up some footage for Movietone News, whose newsreels played in theaters across America. But was this assignment a cover for another, more covert purpose?

The All Stars staged a series of exhibition games throughout Japan. Berg appeared in some of these games and even had two hits. The rest of the time he was left to his own devices. When the team played in Omiya, Berg quietly absented himself on the pretext of illness and stayed in Tokyo, about 12 miles away. He donned a kimono and sandals, combed back his thick black hair, and bought a bouquet of flowers. He was in Japanese “disguise,” a transparent ploy, because his 6’1” height towered over most Japanese of the period.

In any case, he repaired to St. Luke’s Hospital, seven stories high and boasting a belltower. Most Japanese buildings were wooden and low-slung, in part because of earthquakes and in part because of a decree that no building could “look down” upon the Emperor’s palace. St. Luke’s was one of the tallest buildings in the Tsukiji district of Tokyo.

Berg pretended that he wanted to visit Elsie Lyon, daughter of the U.S. ambassador, who had just given birth. Ever the phantom, he got past the receptionist and even Elsie’s mother, who was guarding all access to her daughter. He never even met Elsie, however, but instead went to the hospital’s piazza on the seventh floor. Climbing the belltower, he took out his hidden camera and filmed a breathtaking panorama of the Tokyo skyline. Mission accomplished, he managed to leave the facility without detection.

Wartime Opportunities & Joining the OSS

With his career winding down, World War II offered Berg new opportunities for his talents. In an atmosphere of global war, the United States’ Latin American neighbors assumed a new importance. Nelson Rockefeller recruited Moe for the Office of Inter-American Affairs, an agency designed to strengthen pan-American bonds while at the same time negating Axis propaganda and influence. It was an opportune moment, since Berg finally retired from baseball on January 14, 1942.

President Franklin Roosevelt felt that existing American intelligence agencies were inadequate for the current emergency. He called on William “Wild Bill” Donovan to create a spy network of the first order. The resulting Office of Strategic Services was one of the finest intelligence-gathering operations to emerge from the war.

Berg left the Office of Inter-American Affairs and joined the OSS. Little is known about Berg’s apprenticeship as a novice spy. He apparently went through the usual courses, learning codes, ciphers, and such “routine” skills as safecracking and lock picking. Judo and weapon handling were part of the curriculum, but Berg later had the embarrassing habit of dropping his gun!

Rumors of Involvement in Yugoslavia & East Germany

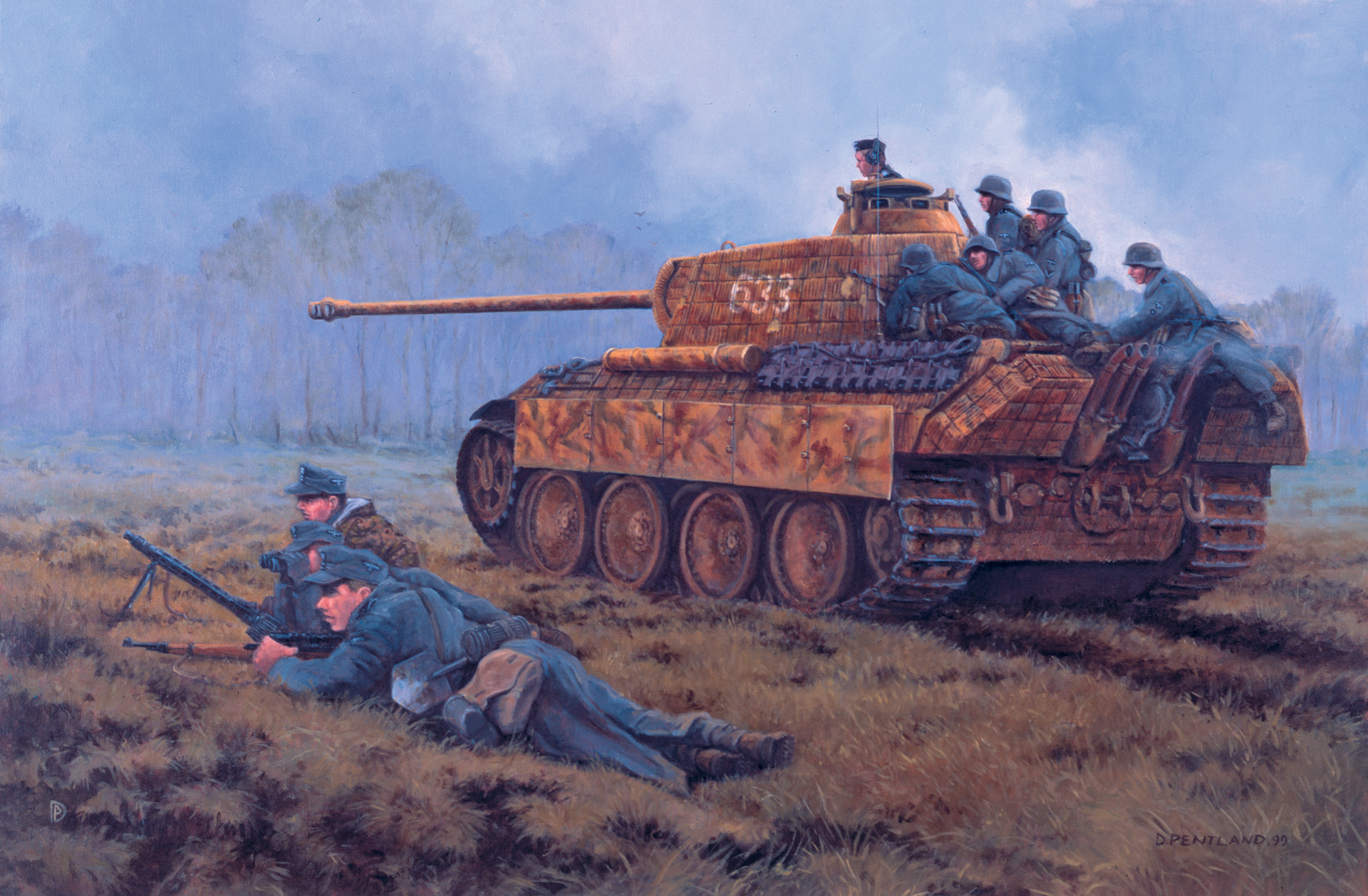

Some have claimed Berg parachuted into Yugoslavia, his mission, to advise Tito. Others insist he traveled incognito through Nazi Germany in 1944-1945, in double jeopardy as an American agent and Jew. Recent biographies have largely debunked these tales of derring-do. We do know Berg was involved in a mission to discover just how close the Germans were to developing an atomic bomb.

The roots of Berg’s quest can be traced to 1938, when German radio-chemist Otto Hahnn bombarded uranium with neutrons, producing atomic fission. This splitting of the atom was a first step in developing a nuclear weapon of unimaginably destructive power. Between 1933 and 1941, many prominent physicists came to the United States, including Albert Einstein and Enrico Fermi. But the man who was considered the greatest theoretical physicist in the world, German Werner Heisenberg, stayed in the Fatherland. He was no Nazi, but a patriotic man who did not want to abandon the country of his birth.

During the war there was a great fear that the Germans might be ahead of the Allies in atomic research. In mid-1944, Berg was sent to newly liberated Rome to consult with certain Italian scientists who had known and worked with Heisenberg. Berg took a crash course in physics and then was on his way overseas. He was accompanied by fellow OSS agent William Horrigan, whose code name was Remus. Berg’s was Romulus, twin brother of Remus and legendary founder of the Eternal City.

When he interviewed an Italian colleague of Heisenberg’s, he found out the scientist was living in southern Germany. Since the OSS was uncertain of Heisenberg’s whereabouts, this intelligence at least narrowed the field. Then there was a break. Swiss physicist Paul Scherrer often arranged lectures at his Physics Institute in Zurich. Berg found out that Heisenberg was to be a featured speaker. Scherrer was not an OSS agent, but he did clandestinely cooperate with the Allies, an offense in neutral Switzerland. By 1944, the OSS was becoming obsessed with Heisenberg. As early as 1942, there had been plans to kidnap him.

Moe Meets With Heisenberg

Berg was dispatched to Zurich to attend the lecture; it was hoped that Heisenberg would reveal something of Germany’s atomic research progress. Berg’s orders were unequivocal. If Heisenberg revealed that the Germans were indeed close to developing a bomb, Berg was to shoot him on the spot.

The lecture, which took place on December 18, 1944, was a modest affair with about 20 graduate students attending. Heisenberg, a frail-looking man of 43, began talking about the s-matrix theory. It was an incomprehensible, even boring, topic to a nonspecialist, but Berg managed to keep awake. The former ballplayer outdid himself, successfully passing himself off as a Swiss physics student, though by some accounts he assumed the role of a French merchant or Arab businessman. Berg’s German was good, but much of the technical jargon must have gone over his head. Still, the American could understand enough to sense that maybe, just maybe, the Germans were not such a threat after all.

Later, Berg made certain he attended a dinner party hosted by Scherrer. Professor Heisenberg was also there, and Berg noted that the German remarked his country had lost the war. This was hardly the manner of a die-hard patriot. After dinner Berg and Heisenberg “accidentally” left the house together and chatted for a moment or two. Berg could have killed Heisenberg at that moment, easily covering the assassination under the cloak of darkness. Heisenberg had no inkling of the mortal danger he was in, since he was completely fooled by the American’s Swiss-accented German.

It was the moment of truth, but in the end Berg let Heisenberg live. There was no indication that the Germans were ahead in nuclear research, so assassinating Heisenberg would have served no purpose. Berg quickly relayed his impressions to his superiors, who were relieved. It was said that Roosevelt himself knew of Berg’s Swiss mission, a point of pride for him in later years.

Hard Times in Later Life

After the war the OSS dropped Berg, a source of great disappointment to him. As he grew older his eccentricities also grew, and during the last 20 years or so of his life he was a rootless wanderer, sponging off friends and relatives for food and shelter. Virtually penniless, he had one suit of clothes, which he dutifully washed—or so the story goes—every night. He died at the age of 70 on May 29, 1972.

Moe Berg was a sincere patriot who served his country to the best of his ability. In retrospect, though, many of his exploits seem either exaggerated or of dubious merit. It is often claimed that Berg’s 1934 film of Tokyo was an invaluable reference for the Doolittle Raid planners. There can be no doubt the film was consulted, but its importance has been overblown. Berg’s rooftop footage was only a few seconds in duration, and eight years old to boot. It is well known that Captain Steve Jurika, a U.S. Naval attaché in Tokyo, spent years preparing detailed maps of the city’s gun batteries, barracks, factories, railroad tracks, and other potential targets. Jurika left only in 1941, so his information was up to date.

Berg’s Swiss mission in 1944 seems more a product of OSS obsession than anything else. Hitler’s Reich was on its last legs, and the idea that the Führer would let his top scientist go to Switzerland at such a critical time is ludicrous, especially if a German atomic bomb was close to being operational. The idea that a German scientist would divulge secrets in a public lecture is also absurd. What might have been a valid concern in 1942 made little sense with Germany tottering on the brink of collapse.

Morris “Moe” Berg could have been an accomplished lawyer or professor of linguistics. He chose the semi-celebrity of a third-string baseball player instead, a decision that has prompted some to call him a failure. Berg might not have been a master spy, but he unflinchingly gave his talents in a time of crisis. He was an eccentric, a man who lived life on his own terms, and by that standard he was a success.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments