by Brad Reynolds

On March 25, 1898, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt recommended that two officers “of scientific attainment and practical ability” be appointed to investigate the Samuel P. Langley flying machine and report on its “practicability and potentiality for use in war.” Within a month, a joint Army-Navy board on aeronautics submitted a report on the flying machine, commenting on its military applications—then purely theoretical—but also supporting the development of this technology. Over the next 17 years, formal and informal investments within the Navy would help progress the cause of military aviation and the eventual incorporation of this technology into the fleet.

[text_ad]

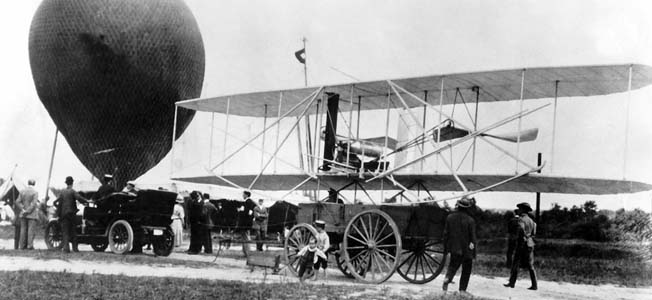

Between 1898 and 1908, individuals within the Navy would study the progression of aviation by attending public demonstrations and air meets around the world. After the initial interest, the field of naval aviation was generally an extracurricular pursuit for the military during the first decade of the 20th century. It wouldn’t be until the Wright brothers’ flight demonstrations in 1908 and 1909 and the Rheims Aviation Meet in Paris that the Navy began to seriously think about incorporating airplanes as advanced scouts into the fleet.

The First Naval Aviators

The year 1910 would bring the first bureaucratic internalizations of these commitments, when the Secretary of the Navy appointed Captain Washington I. Chambers as the officer to whom all aviation correspondence should be referred. Though this was a loose designation, it was a step in professionalizing aviation research and setting up an independent aviation unit.

Civilian pilots undertook initial Naval trial flights from specially designed quarterdecks on naval cursers, but the Navy would slowly begin to train officers in the art of flying. After continual lobbying, the federal government agreed to fund naval experimental aviation by means of procuring aircraft, funding a wind tunnel for further research, and even appropriating funds for helicopter development. These federal allocations allowed the Navy to experiment with pontoons, flying boats, navigational devices, and catapults used for launching airplanes off of maritime vessels. With these appropriations, the naval aviation wing evolved from an institutional hobby, to a professionalized force. By the end of 1911, four naval officers had been designated aviators and plans for a permanent naval aviation station were in the works.

Early Testing at Guantanamo

In 1913, the General Board, presided over by Admiral George Dewey, was prepared to begin testing this new technology in fleet maneuvers. On January 6, 1913, the aviation element of the Navy arrived at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where they successfully exhibited their mine and submerged submarine detection ability. During the unit’s eight-week stay at Guantanamo, experimentation with dropping bombs, photography, and wireless transmissions were also undertaken. These trials legitimized the naval aviation units scouting role within the fleet.

The Office of Naval Aeronautics

Later that year, the aviation unit, which now consisted of nine officers, twenty-three men and seven aircraft, was granted a new permanent base of operations in Pensacola Florida. Soon after, the unit would see its first combat action when five aircraft were called to action to support U.S. Marines in the vicinity of Veracruz, Mexico during the Mexican crisis. The unit would be formally incorporated into the Department of Navy later that year as the Office of Naval Aeronautics.

Over the next two years, the Navy would continue professionalizing the aeronautics service. They would explore armaments, develop a gyroscopic bombsight in early 1916, and continue to wrestle with wireless radios. The Secretary of War also recommended that the Navy cooperate with the Army to jointly develop combat aircraft. Cooperation between the two branches would ensue, creating the Aeronautical Board, which facilitated interagency aeronautics cooperation during World War I and World War II.

The Department of Navy was a pioneer in the field of military aviation. Though the institution was skeptical at the beginning, the belief and motivation of a small group of officers kept their vision alive. As the private aeronautics industry began to develop and show promise, the Navy had enough faith to invest in this developing field, helping to cultivate what has become one of the key facets of every modern military.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments