By Roy Morris, Jr.

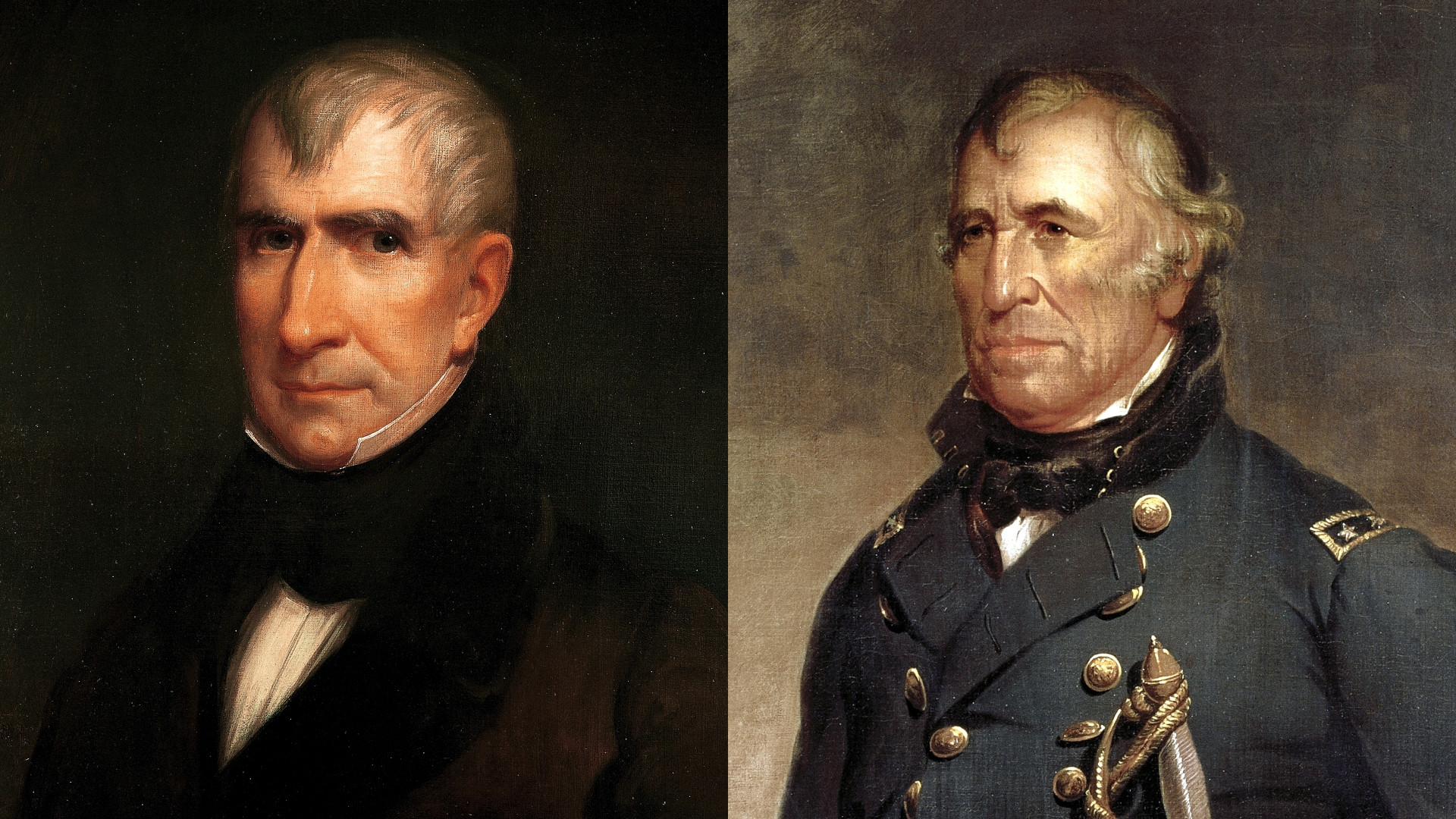

The short-lived Whig Party had a fair degree of success electing candidates for president, winning two of the five presidential elections in which it fielded a candidate. It was no accident that both winners were former generals—William Henry Harrison in 1840 and Zachary Taylor in 1848. The Whigs had come about in the first place as a reaction to Democratic President Andrew Jackson, himself a famous general and war hero. Indeed, the took a page from Jackson’s own campaign strategy when they selected Harrison to run against Jackson’s former vice-president, Martin Van Buren, in 1840.

Mindful of the success Jackson had enjoyed by running on his war record and his homespun background as “Old Hickory,” the Whigs marketed the aristocratic Harrison as a virtual Jackson clone—”Old Tippecanoe”—a nickname they brazenly manufactured from Harrison’s rather inconclusive victory over the Shawnee-led Indian confederation at Tippecanoe Creek, Indiana, in November 1811. Shamelessly comparing Tippecanoe to the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, where Jackson decisively bested the flower of the British Army, the Whigs trumpeted Harrison as the new Jackson. In truth, Harrison’s troops had been surprised and badly mauled at Tippecanoe by the forces of Tecumseh’s brother, Tenskwatawa, but a last-ditch stand had enabled them to hold off the Indians until the enemy withdrew unhurriedly into the woods, allowing Harrison to claim a technical victory by controlling the battlefield. From that distinctly unemphatic triumph, Harrison was put forth nearly three decades later as a suitable successor to Old Hickory. He easily defeated Van Buren, who was saddled with the (then) worst depression in American history, in the ensuing election. “We have taught them how to conquer us,” The Democratic Review lamented. Eight years later the Whigs replicated their triumph by choosing another war hero, this one a good deal more plausible. In the just-concluded war with Mexico, Zachary Taylor had led his army to an unbroken series of victories over much-larger Mexican forces in Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, Monterrey, and Buena Vista. Once again, the Whigs gave their candidate a memorable nickname: “Old Rough and Ready.” And once again, they rode their candidate to victory.

The Curse Begins With Harrison

Unfortunately for the Whigs, they were a good deal less successful keeping their candiates alive once they had elected them to the White House. Harrison, who at 68 was the oldest man (to that date) elected president, unwisely delivered a nearly two-hour-long inaugural address in the biting wind without benefit of a coat or hat. Already worn down by the rigors of the campaign, Harrison caught a cold that worsened rapidly into pneumonia. He died exactly one month after his inaguration. Taylor, who was a still-vigorous 63 at the time of his election, did a little better than Harrison, serving as president for 16 months before ill-advisedly drinking a glass of fresh milk and eating some unwashed fruit at the height of the Washington summer. He caught cholera morbus from the tainted food and died five days later. Four year later the Whigs disintegrated as a political party, undone by the growing turmoil over slavery, which fatally divided their northern and southern wings. They almost enjoyed the last laugh, however. In 1860, a former Whig, Abraham Lincoln, was elected president. He, too, had a colorful nickname—”the Rail Splitter”—but he too died in office, the victim not of a sudden illness but an assassin’s bullet. Once again, the curse of the Whigs came true.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments