by Patricia McBride

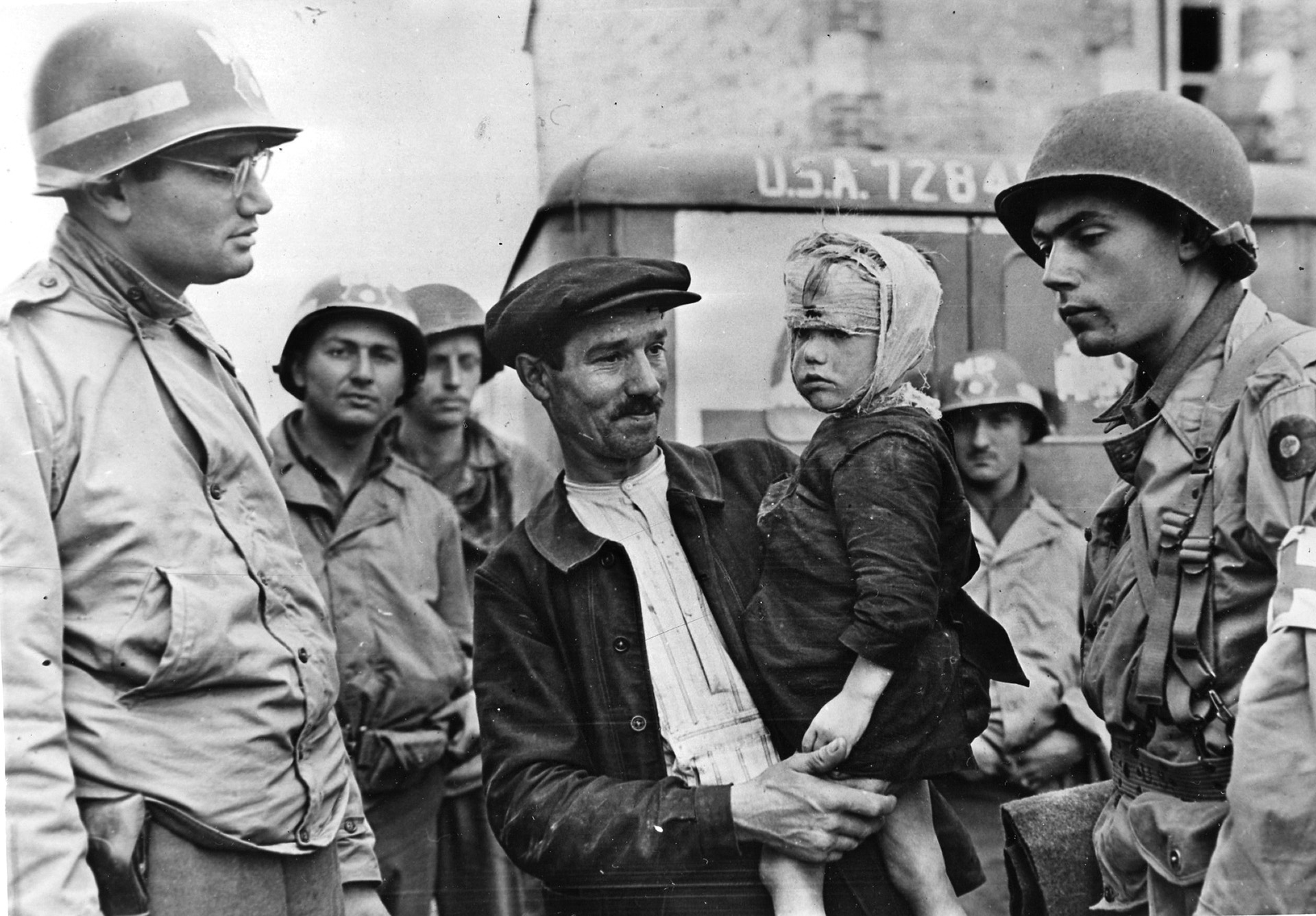

Until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, America had maintained a popular non-interventionist position with World War 2. News of the attack caused a rapid change of opinion, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war the same day. Already in a state of preparedness, America now needed more troops.

[text_ad]

Up until that time, women served only as nurses in the military; the nation was reluctant to admit them into the armed forces. Public opposition was based on beliefs about the traditional role of women as wives and mothers, as well as their sense of protection towards them. Indeed, one congressman said: ‘Take the women into the armed services…who then will maintain the home fires… nurture the children, teach them patriotism… make men of them…so they, too, may march away to war.’

Women Begin to Join the Armed Forces

There had been attempts to allow women into the military earlier in 1941, but they were met with derision in Congress, even after Americans joined the war. Nonetheless, there was a growing realization that the country needed more troops, and the country was changing. Women now had voting rights and for the first time, there were women in government. Politicians pushed through legislation that eventually led to American women joining the forces, albeit in non-combat roles.

There had been attempts to allow women into the military earlier in 1941, but they were met with derision in Congress, even after Americans joined the war. Nonetheless, there was a growing realization that the country needed more troops, and the country was changing. Women now had voting rights and for the first time, there were women in government. Politicians pushed through legislation that eventually led to American women joining the forces, albeit in non-combat roles.

A huge recruitment drive began. Senior Officers toured the country giving talks encouraging women to volunteer. Posters urged women to ‘Share the Deeds of Victory,’ ‘Free a Marine to Fight,’ or ‘Take this great opportunity’. Stirring films in cinemas urged them to join up, portraying the roles they could undertake, always with the goal of releasing a man to fight. Previously in the media, women had been depicted as home-makers, vamps or movie stars; Now they were portrayed with their heads held high, shoulders back, looking smart, independent and determined. The call to arms was a resounding success with almost 400,000 women volunteering to serve in or with the armed forces.

But opposition amongst the public remained, and rumors spread throughout the country. One widespread story was that all serving women were prostitutes supplied with condoms by the military. This resistance to accept women was sometimes echoed in the treatment women received from the men with which they served. Some resented women taking their jobs, especially when their presence meant they would have to go away to fight. Others simply would not believe they were up to the mark. They were soon proved wrong.

Reservists, Auxiliary Corpsmen & Nurses

Women served in the Women’s Army Corps (WACs), in the Naval Reserves (WAVEs), the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve (SPARs), as Air Force service pilots (WASPs), in the Navy Nurse Corps and Army Nurse Corps. These reservists and nurses became some of the most important women in World War 2, supporting Allied efforts at home and abroad. The WASPs, for example, clocked up 60 million flying miles, transporting thousands of aircraft between factories and military bases. They also ferried cargo and took part in simulated strafing and target missions. Others were radio operators, secretaries, cryptographers, laboratory technicians, aircraft maintenance, drivers, aviation operators, and engineers.

In 1942, WACs began to be deployed overseas—mostly in Europe—but others went to the Far East and the South Pacific. Sixteen women in the Army Nurse Corps were killed, 60 women were taken Prisoner of War in the Philippines and a total of 432 died. Their bravery was recognized—1600 service women were decorated for bravery and 565 WACs won combat decorations in the Pacific Theatre.

General MacArthur, speaking at the end of the war, summed up the view of many. He praised the WACS, calling them his ‘best soldiers,’ adding that they were ‘better disciplined, worked harder than men, and complained less.’

Patricia McBride is a freelance journalist living in Cambridge, England. She is interested in social history and particularly in women’s history. She is also a travel writer and author of several self-help books and one novel.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments