By William E. Welsh

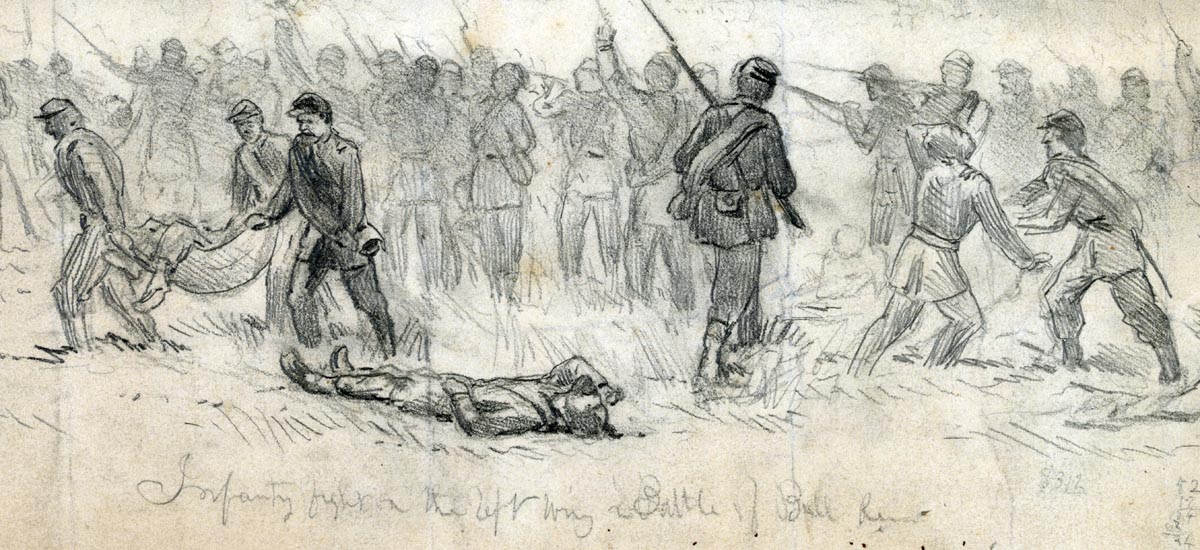

The New Englanders crept forward through the thick woods toward the Rebel position at mid-afternoon. Trading volleys with the Confederates behind the natural trench afforded by the unfinished railroad line during the Battle of Second Manassas in summer 1862 had so far proved unsuccessful throughout the scorching hot summer day. Therefore, the Federals planned a bayonet charge—a rarely used but often effective method of attack on a Civil War battlefield.

The wily Stonewall Jackson had selected the unfinished line of the Manassas Gap Railroad west of Bull Run to conceal his 24,000-strong Confederate corps. For most of August 29, 1862, John Pope’s Army of Virginia had pounded Jackson’s left flank near Sudley Church with one attack after another. Maxcy Gregg’s South Carolinians had parried each and every blow, and even got in a few licks themselves on the determined Northerners. Rather than deploy in the unfinished railroad bed, the Rebels on Jackson’s left flank opted instead for a ridge several hundred yards north of it. But the Confederates inadvertently left a 125-yard gap between two of their front-line brigades when they reformed in the early afternoon and Brig. Gen. Curvier Grover, a savvy West Point graduate from Maine, aimed to exploit that opportunity. Grover told his officers to have their men creep forward until the Confederates discovered them. At that point, the front rank of the 1,500 Yankees was to fire one volley after which they would immediately charge the enemy with their bayonets.

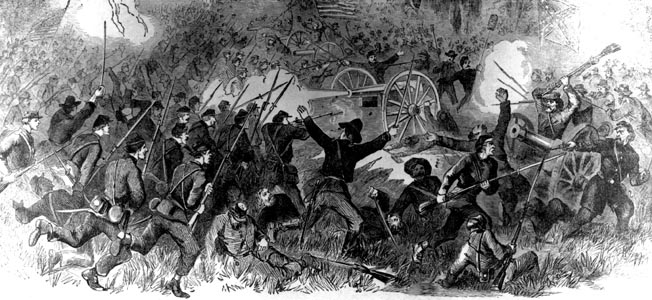

With their hearts racing, the Yankees reached a heavily wooded portion of the unfinished railroad bed undetected. The rifle-muskets used by both sides were frighteningly effective at up to 350 yards, so Grover’s goal was to get to within 100 yards of the enemy to give his men a chance to rush them with as few losses as possible. Gregg’s brigade was nearing exhaustion, but its short but fiery commander, who carried his father’s Revolutionary War sword, could call on assistance from a Georgia brigade to his right and a North Carolina brigade to his left. Grover’s front stretched for a quarter of a mile. His front line consisted of his three most experienced regiments, and the second line of his other two regiments. Suddenly, a blistering volley fired at point-blank range from a Confederate regiment tore into the left flank of Grover’s brigade. This alerted other nearby regiments that a Federal attack was under way. The Yankees returned the volley, and then they charged. “The railroad bank was gained, and the column passed with cheers over it,” wrote Henry Blake of the 11th Massachusetts.

This time it was not Gregg’s South Carolinians that suffered the brunt of the Federal attack, but Colonel Edward Thomas’ Georgians. The Yankees flooded into the Georgians’ position. Thomas’ left flank crumpled. Those who did not surrender were shot, clubbed, or bayoneted. Major Washington Grice’s 45th Georgia, in the center, made a brief stand, but then everyone in the unit fled deeper into the woods. One Georgian said he followed the others in “triple quick time.” As for Gregg’s South Carolinians on the Confederate left, they were in danger of being cut off from the rest of Jackson’s corps. The bullets flew so thick that they “shattered the stocks of many muskets,” Blake wrote, “but the soldiers who carried them picked up those that had been dropped on the ground” and rushed after the fleeing Confederates.

On a shelf of high ground a portion of Thomas’ reeling brigade rallied, but they could not check the momentum of Grover’s charge, which snapped them as easily as if they were a twig on the forest floor. Once again the South Carolinians rose to the challenge. The commanders of the two South Carolina regiments closest to Thomas’ brigade, Major Edward McCrady’s 1st South Carolina, and Colonel Oliver Edwards’ 13th South Carolina, each led several of their companies against the near-victorious Yankees. The Palmetto Staters fired stinging volleys into the ranks of bluecoats. But the New Englanders stood their ground and inflicted fresh losses on Gregg’s thinning ranks.

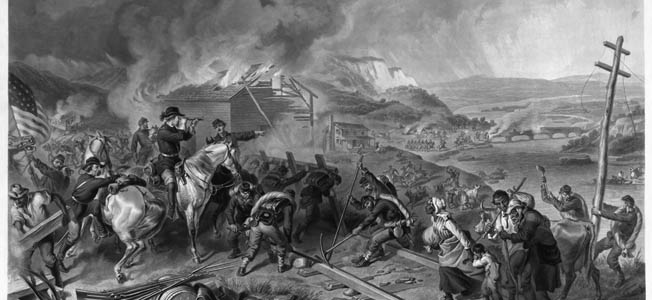

Meanwhile, Gregg was reorganizing his brigade to resist Grover’s breakthrough. All of a sudden 200 South Carolinians with leveled bayonets shrieking the terrifying Rebel Yell crashed into Grover’s right flank. Grover’s losses were mounting steadily, and the support he had been promised to help crush Jackson’s left had never arrived. Grover’s men had been fighting for nearly an hour, and Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill, the divisional commander responsible for the Confederate left, was feeding fresh troops into the fight. While Gregg assailed Grover’s right, fresh troops belonging to Brig. Gen. William Dorsey Pender’s North Carolina Brigade fired crashing volleys into Grover’s left. Grover, on horseback, ordered his regiments to pull back.

The Yankee officers shouted for their troops to maintain their lines as they pulled back, but some of the New England regiments were now taking fire from two, and even three, sides at once. This proved too much for Colonel Gilman Marston’s 2nd New Hampshire in the center, and the men in the regiment ran back over the ground they had advanced, all the while praying they’d make it out alive. Sadly, just as Grover’s brigade was reforming a half mile to the rear, the support he never received–a fresh Yankee brigade–was preparing to go into action. This was typical of Pope’s disorganized, poorly planned attacks throughout the Battle of Second Manassas. Grover’s achievement was proof, in yet another battle in the lengthening war, that Billy Yank was as tough as Johnny Reb. But the Yankees that day lacked generals who could come anywhere close to matching the keen eye, and cool head, of the eccentric, but nearly always successful, former Virginia Military Institute professor, Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments