by Mike Haskew

The 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln was elected to the highest office in the land in November 1860, and the event prompted the secession of numerous southern states beginning with South Carolina the following month. Subsequently, 10 more states seceded from the Union, the Confederate States of America—a new nation—was proclaimed, and the American Civil War began on April 12, 1861, with the firing on Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina.

[text_ad]

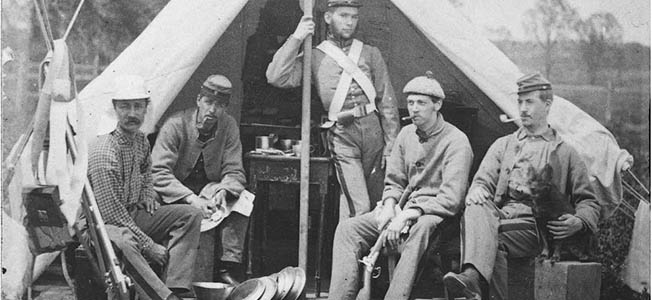

A Republican, Lincoln was considered a direct threat to the sovereignty of the southern states and the institution of slavery. Within three days of the opening of hostilities, he called for 75,000 volunteers to defend the Union. He vigorously prosecuted the war, although a succession of commanding generals proved disappointing in the field. Following the Battle of Antietam, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, ostensibly freeing all slaves in territories in rebellion against the United States. The document was symbolic of the nature of the conflict; however, Lincoln’s primary objective was the preservation of the Union.

The Apppointment of Ulysses S. Grant

In the spring of 1864, Lincoln appointed General Ulysses S. Grant commander in chief of all Union armies in the field, and Grant relentlessly fought General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia for the next year, culminating in the surrender of the Rebel army at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Two weeks later, the Confederate Army of Tennessee, under General Joseph E. Johnston, surrendered to Union forces in North Carolina under the command of General William T. Sherman, and the Civil War was effectively over.

Despite a stiff challenge from Democrat George B. McClellan, Lincoln was elected to a second term as president in November 1864. He advocated reconciliation and intended to pursue a moderate policy of reconstruction with the former Confederate states. However, he was shot by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C., on the night of April 14, 1865, and died the following morning. His assassination precipitated a period of harsh reconstruction in the South.

Always a Westerner

Born in Hodgensville, Kentucky, on February 12, 1809, Lincoln was considered a Westerner, and a Washington outsider when he was elected president. Prior to the Civil War, he served four terms in the Illinois state legislature and his most notable political accomplishment had been his failed bid for the U.S. Senate in 1858. Lincoln and Senator Stephen A. Douglas engaged in a celebrated series of debates during that campaign. Lincoln was a self-educated attorney and was said to have studied law books on his own by lamplight. He became a successful trial lawyer and practiced for a time in Springfield, Illinois, with John T. Stuart, the cousin of his wife, Mary Todd. Lincoln’s personal life was filled with tragedy, as two sons, Edward and Willie, died young.

Lincoln’s legacy is that of a national father figure, whose compassion was boundless. His Emancipation Proclamation, Gettysburg Address, and second inaugural address are treasured among the documents of American history, and Lincoln is memorialized across the nation.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments