By William E. Welsh

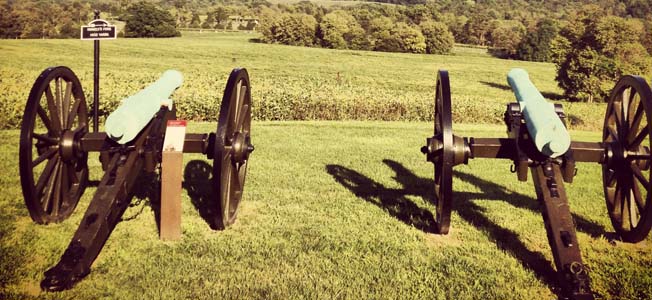

The harvest of death in the farm fields of western Maryland was a heavy one on September 17, 1862. A visitor standing in the Sunken Road in the center of Antietam National Battlefield can see in close proximity to each other two upturned cannon barrels. These mark where two of the six generals slain that that terrible day fell in battle.

The two “mortuary cannon” at the Sunken Road are memorials to Confederate Brig. Gen. George B. Anderson, whose North Carolina brigade defended the right side of the road, and to Union Maj. Gen. Israel Richardson, whose II Corps division overwhelmed the Tarheels in a desperate mid-day struggle. The Battle of Antietam is known as the bloodiest one-day battle of the Civil War because the two sides suffered a combined total of more than 23,000 casualties.

Following The Battle Lines

The way the battle unfolds at Antietam makes it easy for the visitor to move from north to south in the park where the action started on the Confederate left flank, shifted to the Confederate center, and ended on the Confederate right flank. Located on the north end of the park, the visitor center is situated on high ground where General Robert E. Lee massed his artillery to receive the attack of three Union corps throughout the long morning. The visitor center has a 26-minute introductory film, extensive exhibits, and a large bookstore.

Visitors can take a self-guided auto tour that begins at the Dunker Church, which was the objective of the Union forces attacking the Confederate left flank. The rolling farmland of Antietam, where corn stood six-feet tall in September 1862 in the fields surrounding Sharpsburg, is beautiful to behold. But the beauty belies the carnage that occurred that day as Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, recently restored to command of the Army of the Potomac, sought to smash Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Lee sought to consolidate his army, a large part of which had been detached to seize Union-held Harper’s Ferry, before McClellan could strike it. Following several small battles that occurred in three gaps of South Mountain three days earlier, Lee chose the high ground west of Antietam Creek as the place for his army to assemble.

Mumma Farm, Dunker Church and the Observation Tower

The driving tour goes from the Dunker Church to the cornfield on the D.R. Miller farm that exchanged hands multiple times as wave upon wave of infantry swept back and forth in attack and counterattack until the cornfield was blanketed with dead bodies. The auto tour then winds its way to the Mumma Farm, just north of the Sunken Road, which the Confederates torched to deny it as a sharpshooter point to the attacking Yankees.

An observation tower on the southern end of the Sunken Road offers a 360-degree view of the battlefield. The tower helps visitors see how the folds of the landscape played an important role in concealing the advance of the attacking Union troops.

How A.P. Hill Made History

Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill’s Division had the difficult task of protecting Lee’s center. Just before the Union attack on that position, Hill and Lee rode past Anderson’s 1,200 North Carolinians and also Brig. Gen. Robert Rodes 800 Alabamians in an effort to steel them for the difficult fighting ahead. One plucky officer, 6th Alabama commander Col. John B. Gordon, said to Lee, “These men are going to stay here, general, ‘til the sun goes down or victory is won.”

One of the greatest military feats of the war, as well as one of the most iconic images of the Battle of Antietam, awaits the visitor on the southern end of the battlefield where the Union IX Corps attacked Lee’s right flank. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside dithered most of the day held up in his crossing of the Antietam by a small brigade of Georgians led by politician-turned general Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs. The Rohrbach Bridge, which became known as Burnside’s Bridge, after the battle, is one of the most picturesque locations of any Civil War battlefield in the nation.

The great military feat belonged to Confederate Maj. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill, whose Light Division conducted a 16-mile forced march from Harper’s Ferry. Hill’s Light Division arrived just in time to defend Lee’s crumbling right flank. The forced march forever immortalized Hill and his men.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments