by Terry Gore

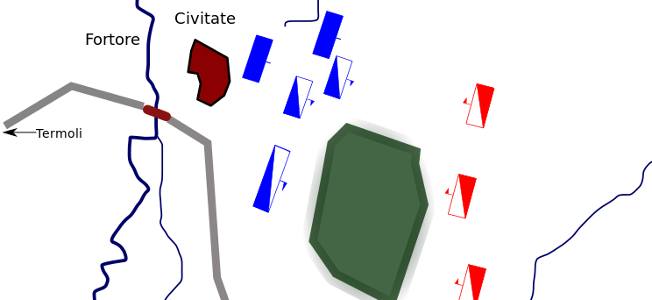

It is true that the Normans were greatly outnumbered at the Battle of Civitate, likely by as much as two to one or more. The might of the papal army rested in the cadre of Swabian swordsmen from Germany. These fighters were mailed heavy infantry who normally fought on foot, wielding deadly two-handed swords. At Civitate, they fought mounted at first, making their usual tactical skill difficult to emulate.

[text_ad]

As William of Apulia noted (quoted in Osborne), they were “quite unskilled in the management of their horses; more formidable with the sword than the lance. When fighting with the latter they have trouble in controlling their steeds and do not inflict dangerous wounds. Their swords, on the contrary, are long and very keen. They often cut in two an opponent from head to leg. When unhorsed, they continue to fight, preferring death to flight.” Why did they fight mounted, then?

The Normans were mounted and the Germans, out of hubris, felt they could match them head to head fighting on horseback. They had never faced a Norman charge before and felt a confidence in their own abilities; after all, they were of much larger stature than the Normans, so felt they would be able to defeat them with ease. They almost did.

Unarmored Peasants With Spears & Shields

The bulk of the papal army—the Lombards and Italians—was for the most part on foot, but a significant number of nobles and their retainers were also mailed and fought mounted with spears and lances. They were tough fighters when battling against their own countrymen, but had proven again and again to be unequal to fighting the Norman milites (or knights). The foot soldiers were mainly unarmored peasants with spears and shields. Some were unarmored archers, lacking any offensive or defensive weaponry other than the short bow.

There were small numbers of German cavalry and mercenaries, both horse and foot. The German cavalry were good fighters, used to charging with the lance in wedges similar to those of the Normans, but there were only a handful of them at the battle and their influence on the outcome was insignificant. Likewise, the mercenary foot were better armed and armored than the native Italians and Lombards, but again were too small in number to matter.

The Backbone of Norman Armies

William of Apulia noted that the Norman army contained foot soldiers as well, but that they had deserted to avoid starving. That is likely, because the Calabrian and Apulian native footmen had been more or less compelled to accompany the Normans. There were also likely small numbers of Norman foot soldiers, archers, and spearmen who accompanied Norman armies from battles in England to Greece during the latter half of the 11th century. Again, these numbers would have been small, but they were probably present at Civitate.

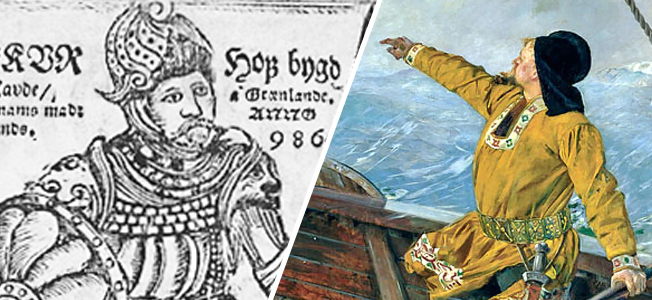

The Norman milites were the backbone of the Norman armies. Riding strong-bred destriers, or warhorses, the Norman knights relied on the kinetic energy of their charges, using long stirrups and high-pommelled saddles to deliver incredible force when contacting an enemy. The Normans also retained the wedge formation from their Viking forebears. The wedge allowed a massive force to be concentrated on a small frontage.

By focusing the point of attack, the enemy line could be penetrated and broken through. Then the rear ranks of the wedge would widen the gap. Once through the enemy line, the Normans would turn and attack the milling, disordered enemy mass in the rear, further demoralizing and fragmenting them. This tactic worked again and again and made the Normans masters of most of the battlefields upon which they fought.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments