By Richard A. Beranty

On the veranda of his temporary headquarters in a Dutch country house outside Veghel, Holland, renowned Luftwaffe General Kurt Student played lunch host to an old comrade, the chief of staff of the German Seventh Army. September 17, 1944, was a peaceful and pleasant late summer day in the Netherlands. Before dessert arrived, their talk turned to Germany’s ongoing setbacks in the war, first in Russia and now in France. Student, personally appointed by Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring five years earlier to build and command its Fallschirmjager (airborne) forces, told his guest the reversal was largely due to Germany’s inability and Hitler’s reluctance to mount airborne operations.

From across the table, General Rudolph von Gersdorff defended Student, his friend and superior. Nonsense, he said. Because of Student, Germany was the very first to pioneer air assault. He cited the invasion of Crete and especially the capture of Eban Emael, the Belgian fortress taken by only 100 Fallschirmjager during the invasion of the Low Countries in May 1940.

“We make small successful experiments and then we stop,” Student retorted. “I am speaking of the real thing.”

Just then, a faint but familiar mechanized roar came from the south, splitting the air around them. The men got quiet and looked skyward. They saw a dark spot on the far horizon that grew thicker and wider while the steady hum of airplane motors grew louder. Suddenly, the air force general jumped from his chair, ran to the lawn, and raised both his arms in a sweeping motion.

“This is what I was speaking about,” he shouted to his friend. “The real thing!”

Happening in front of their eyes was phase one of Operation Market-Garden, the British-inspired plan to create a 60-mile wedge inside Nazi-held territory and reach the Dutch city of Arnhem. To do so, one British and two American airborne divisions were landed west to east across Holland with orders to destroy enemy forces and seize key roads and bridges needed by advancing infantry and armored units of British XXX Corps in its dash for Arnhem.

The operation was designed by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, commander of the Allied 21st Army Group, and approved by Allied leaders. Its ultimate objective was to cross the Lower Rhine at Arnhem and sweep into the Ruhr, the industrial heart of Germany, possibly ending the war by Christmas 1944. Its success was predicated on one critical element—timing. The British ground force had approximately 56 hours to relieve the paratroopers at the far end of the corridor, who in theory would be holding the Arnhem bridge.

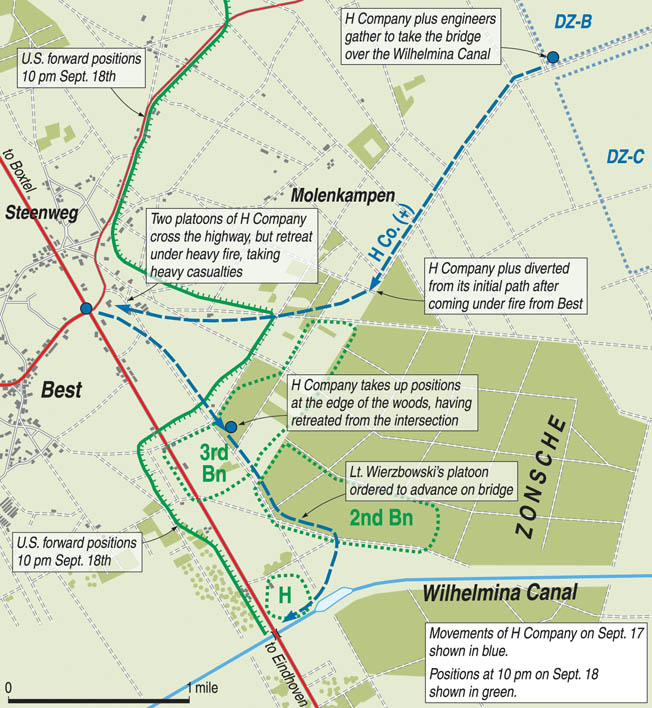

The Americans dropping from the sky near General Student that day were men of the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), 101st Airborne Division. They had been given one of the least spectacular assignments in Montgomery’s plan, mainly to secure several small towns, cover passage of the Wilhelmina Canal waterway, and act as a buffer between the 501st PIR to its north and 506th to its south. The regiment’s landing in the flat fields of Drop Zone B near Zon went off perfectly. In just over an hour, better than 90 percent, or nearly 1,500 men, had gathered in their assembly areas.

Landing at Best

One of the towns assigned to the 502nd was Best, Holland, a nondescript place of about 30 houses, a church, and one gas station situated on the main road outside of town. That roadway led south to the city of Eindhoven, a major objective of the 506th. Today, the A-2 Highway, whose odyssey begins in northern Europe and ends in southern Spain, hugs the eastern side of Best with its 25,000 inhabitants. The Zonsche Forest, a pine plantation sown by the Dutch years before the war, runs along the A-2’s other side. About the size of a small American city, Best’s checkerboard tree plots and distinctive firebreaks spaced every 30 yards were ideal landmarks for pilots of C-47 transport aircraft and the 101st Airborne men dropping from the sky.

Best was important to the Allied assault because of its proximity to the Wilhelmina Canal and the two bridges that crossed there—one pedestrian and one railroad—just in case either was needed by Montgomery’s advancing ground forces. Secondary orders for the 502nd were to capture both spans, set up defenses around them, and block the main road running south to Eindhoven.

At first only one platoon was assigned to the mission. Division intelligence determined the area was manned by a few squads of German troops—kids and old men. Afterward, this estimate was sheepishly described as “a minor error.” After some persistence by 3rd Battalion command, the platoon was increased to company strength, augmented by 40 combat engineers and a light machine-gun section. Fourteen minutes after assembling, H Company was headed southwest on its four-mile march toward Best under the command of Captain Robert E. Jones. It was about 1:45 pm.

While G2 estimates of enemy strength at Best were grossly inaccurate, its assessment was quite understandable. There was no way of knowing that over the past two days hundreds of German troops had detrained in the area, including parts of the Fifteenth Army in retreat from the Scheldt Estuary to the west, tired units from as far away as Normandy, men from the 59th and 245th Divisions, and two SS police battalions. The exact number is unknown, but at the very least 1,000 troops, probably many more, had arrived at Best by rail the day before, and many more would follow with plenty of artillery. To make matters worse for the 250 Screaming Eagles advancing on their target, six German 88mm cannon spaced at 50-yard intervals also stood in their path.

The paratroopers began to receive small arms fire at about 3 pm from a roadblock the Germans had established at the Best intersection. It was not an ordinary roadblock, as one of the powerful 88s was positioned right alongside the pump at the town’s gas station with smaller artillery in support. To orient himself on the march, Captain Jones used the church steeple at Best as his guide but lost sight of it going through the Zonsche Forest. He thought that if he kept on that approach it would lead him to the canal halfway between the railroad and highway bridges.

Instead, the men emerged from the forest 600 yards north of where he had intended, in the opposite direction of the bridges and only 200 yards away from the roadblock. “Meeting strong resistance,” Jones radioed battalion headquarters at 4 pm. The situation was about to get worse.

Within 10 minutes of his call, an enemy column of 12 trucks hauling a number of 20mm cannon was spotted barreling south down the arrow-straight roadway toward Best. Word was quickly passed among the paratroopers to hold all fire, suck the convoy in, and then destroy it. But not everyone got wind of the plan in that short time. A German motorcyclist who was riding well in the lead was shot dead from the seat of his bike. It brought the column to a stop, and its men and guns deployed quickly, adding 200 more Germans to the fight. The plan to capture Best was now out of the question for Jones. Facing attacks from three sides and with sniper fire demonizing his rear, he abandoned the area without pursuit. By 6 pm, his men were digging foxholes on a line in the fading light somewhere inside the Zonsche Forest.

Approach at Night

Despite this setback, the battle plan as originally conceived by headquarters was apparently still on. Before the company withdrew from Best and with no understanding of the situation, battalion command insisted that Jones send 2nd Platoon, reinforced by 26 engineers and part of the machine-gun unit, to capture both canal bridges and set up defenses around them. It was a next to impossible task for such a small group to accomplish with the hundreds of Germans in the area. Making their mission more difficult, the enemy had infiltrated the southern edge of the Zonsche Forest during the afternoon and placed machine guns at every third or fourth fire lane the men had to cross, giving enemy gunners a 400-yard unobstructed view down the breaks.

Lieutenant Edward L. Wierzbowski commanded 2nd Platoon. Night was coming, and so was the rain. Wierzbowski’s men were as apprehensive about the approaching darkness as they were about the assignment. From the moment they met machine-gun fire at the first fire lane, Wierzbowski knew what was in store and gave the necessary orders. Slowly, methodically, and one by one, his men bounded across each firebreak as stealthily as possible, unaware whether it was covered by a machine gun. At some breaks, the bullets traced their way in front or behind them; at other breaks there was no fire at all. It was a slow trek but, incredibly, no one was hit. The rain increased to a cold drizzle when 2nd Platoon emerged from the pine plantation at about 8 pm.

Hidden by darkness, an hour later the men reached the dike, some 500 yards east of the highway bridge. Two large derricks that the Dutch used to unload goods from the canal had to be crossed. On the water side of the complex ran a steel catwalk hanging out over the canal. Thanks to a dark and rainy night, the paratroopers climbed, crossed over, and descended the mud-covered and slippery metal framework undetected. Those making their way across would have been so many sitting ducks had a flare gone up.

The Germans did not notice, and once again the men were along the dike, 30 yards away from the bridge, when a German soldier from across the canal innocently unloaded his rifle into the air, sending bullets well over their heads. It brought every man to a silent stop. Wierzbowski was sure they had not been discovered. He slithered his way through the wet grass to his lead scout, Private Joe E. Mann, and whispered in his ear, “I think we’re all right. Come along.”

Digging In

The two had not crawled far when they saw Germans changing guard at the nearby entrance to the bridge. As one soldier came off, another soldier came on. What they did not see was the route of the sentry’s post, which took him in a wide circle around the men. They were belly down in the center of his rounds. For an intense 30 minutes Wierzbowski and Mann waited silent and motionless, unsure of what to do while the sentry made several circles around them. They could not backtrack, being so close that any movement would give them away. They could not rush the guard either. He was talking to his buddy across the canal, who was also on duty.

The platoon waited, too. Not hearing from Wierzbowski for so long, several of his men started to climb the dike, and others followed. When the fourth man reached the top, five German machine guns from across the canal opened fire. The fury of the barrage made some of the Americans flee into the woods and out of sight. But it was the break that Wierzbowski and Mann needed. They jumped up when the firing started and ran back toward their men. Wierzbowski led those who had not run away to a position 60 yards from the canal, where they dug in for the night. He then counted his assets: one machine gun with 500 rounds, one mortar with six rounds, one bazooka with five rounds, and 18 men. Awake and on the move for 24 hours, they were glad when enemy mortars quit firing on their position at about 3 am.

For German commanders on the other side of the bridge, there was no time to lose. They worked quickly, piecing together the hodgepodge of groups massing at the Best rail line to meet the Americans. It seemed to be working well initially. German mortar squads and artillery units were making a difference. H Company, holed up in the Zonsche Forest, lost 30 men from enemy fire before daylight arrived. Lt. Col. Robert G. Cole, 3rd Battalion commander, moved his remaining two companies south to the canal, but after nightfall they also were digging foxholes inside the forest because of strong enemy firepower.

Jones and Cole were unaware, but their positions in the Zonsche Forest that night were only 1,000 yards apart. Neither did they know the whereabouts of Wierzbowski and 2nd Platoon, which was becoming worrisome. Two patrols went in search but returned because of enemy fire.

“Get a platoon down there to find Wierzbowski,” Cole radioed Jones at 11:30 pm. Jones did so, reluctantly sending 3rd Platoon. It made three different attempts and was driven back each time. It would be another day before anyone learned the fate of 2nd Platoon.

“They’ve been annihilated beyond a doubt,” Cole told his executive officer, Wyoming native Major John P. Stopka.

Hay For Cover

Cole’s men were being pushed deeper into the woods by enemy fire when at 4 am on September 18 Colonel John H. Michaelis, commander of the 502nd, finally took notice. He ordered the three companies of 2nd Battalion, under the command of Lt. Col. Steve A. Chappuis, to free up 3rd Battalion, which was stuck in the forest, march on Best, and secure the bridges once and for all. Michaelis had been holding Chappuis’s men in reserve in case they were needed to support the 506th driving toward Eindhoven, where division intelligence said the bulk of the enemy forces were located. Second Battalion moved out at 8 am on Cole’s right straight toward the highway.

“It was just like the book,” explained Lt. Col. Allen Ginder of regimental headquarters, who watched the assault unfold. “The Dutch had been haying and the fields ahead were covered by these small piles of uncollected hay. That was the only cover. From left to right the line rippled forward in perfect order and with perfect discipline, each group of two or three men dashing to the next hay pile as it came their time. You would have thought the piles were of concrete. But the machine gun fire cut into them, sometimes setting the hay on fire, sometimes wounding or killing the men behind them. That did not stop any except the dead and wounded.

“One man went down from a bullet. I heard someone yell, ‘Sergeant Brodie, you’re next.’ Another man behind the hay pile yelled, ‘Brodie’s dead, but I’m coming on’ and he jumped up and ran ahead. It was like a problem being worked out on a parade ground. The squad leaders were leading; the platoon leaders urged them on. Those who kept going usually managed to survive. The few who tried to hold back were killed.”

Chappuis also watched as his battalion took a beating from artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire coming from beyond the highway. More than 20 percent of his command was gone, including eight officers who lay dead in the field. To continue the advance as ordered meant the destruction of his battalion. He stopped the attack and pulled his men back to reorganize.

“Some of the guys near me were bunched up,” said Sergeant Lud Labutka of E Company. “I even yelled at them to scatter. You’re never supposed to get close to the next guy. That’s what they taught us—don’t bunch up because that’s what the enemy is looking for. Then a mortar shell hit three of them. It landed in one guy’s lap, tearing off his legs. Another one was dying. He asked me to recite the Act of Contrition to him. He died right there in my arms.”

The Death of Cole

Michaelis had no reserve forces available to send in or to request from division headquarters. First Battalion’s three companies were assisting the 501st to the north at St. Oedenrode, and the 506th had not yet captured Eindhoven. As Chappius’s fall back began, German infantry saw an opening and started to infiltrate Cole’s lines in the forest by twos and threes. Cole rang up Michaelis from inside his two-man command post asking if close air support was available and then left his foxhole for a short while.

When Cole returned, he found radioman Sergeant Robert E. Doran dead. A shell had hit the Connecticut native and blown his skull apart. Cole was wiping blood and brains off the radio’s headset when Stopka arrived with news that a unit of Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter bombers was coming over, having escorted gliders into the area just minutes before. Their appearance on that day was the only stroke of luck the 502nd would have during the entire battle. It was 1:30 pm.

Faced with being overrun, few of Cole’s men were willing to leave the safety of their foxholes. When the Thunderbolts swooped in low to strafe, their bullets clipped the edge of the forest where the men were dug in. Stopka quickly organized the placing of orange flags to mark their position. The planes came over for a second run and adjusted their aim, which slowed enemy fire considerably. Cole walked out of the tree line and into an open field. He stood and watched the air attack with one hand shielding his eyes. A German sniper inside a farmhouse 100 yards away put his sights on the exposed target. He fired his rifle and hit the 29-year-old in the temple, killing him instantly. Third Battalion now belonged to Stopka.

Cole’s death was a profound loss to his men. The Texas-born West Point graduate was an imposing and seemingly fearless commander highly respected both as a leader of men and dedicated soldier. When he died, paperwork was already in place to recommend him for the Medal of Honor for leading a bayonet charge against enemy positions in Normandy three months earlier. The citation was approved posthumously. Cole’s body is interred at the U.S. Cemetery in Margraten, Holland.

Cole’s influence on his command was such that many found it difficult to believe he was actually gone, but they gained some solace moments later when the German sniper was gunned down fleeing the farmhouse. On the same day Cole was killed so too was his enemy counterpart, the German commander at Best.

Best’s Bridge Blown

Wierzbowski, positioned east of the highway bridge that morning, had no way of knowing the rest of 3rd Battalion was bogged down in the nightmare of the Zonsche Forest from which he had escaped the night before. His men heard distant fire throughout the night and began to think support might be coming their way. Even more encouraging, the overnight rain had quit and daylight provided their first clear view of the bridge—a tantalizing 60 yards away and a short run for a conditioned paratrooper.

The Germans had even pulled off their sentry at the near entrance, but any movement from the men’s foxholes drew an instant response from the enemy. They could not stand up to stretch, scratch, or urinate. “Every time we raised up to start toward the bridge we drew heavy fire from two sides,” said Private James C. Hoyle, one of Wierzbowski’s scouts.

Fire was coming from German troops— most of whom had been scattered south from Best during 2nd Battalion’s drive across the hay field—massing for an attack from across the highway. Wierzbowski saw what was coming and ordered all weapons to fire on his order at 50 yards. The lone machine gun proved most effective, leaving 35 Germans on the ground. The Americans continued to watch.

At around 10 am, a German soldier and a Dutch civilian walked up to the far entrance to the bridge. They talked for some 15 minutes and left. Wierzbowski thought nothing of it at the time, least of all that the two were setting a timed fuse to detonate an explosive charge already in place. Precisely at 11 am, a powerful explosion lifted the 100-foot structure, and it crumbled into the water. Dirt, dust, and debris dropped on the men in their foxholes. While the bridge at Arnhem was a bridge too far, the bridge at Best was a bridge ever so close. It was now a pile of broken concrete and twisted steel lying across the Wilhelmina Canal. All the men could do was wait for battalion command to arrive—but not before making some noise of their own.

German Attack on the Paratroopers

Joe Mann and Jim Hoyle, Wierzbowski’s main scouts who led the mission throughout, grabbed some weapons and crawled toward the canal to do just that. They spotted a German artillery dump to their west, which Mann lit up with two rounds from the bazooka. Over the next hour the pair killed six Germans advancing on their hideout until enemy fire finally penetrated their lair. Two bullets tore into Mann, hitting both of his shoulders. He handed the bazooka over to Hoyle, who aimed at a German 88 positioned 150 yards down the canal, hitting it with one round.

Wierzbowski was only happy to keep pressuring the enemy. A truck hurrying ammunition away from the destroyed 88 exploded into a fireball when it was hit by American machine-gun fire from across the canal. He also sent three men toward the derrick, who returned in short time with four enemy prisoners, three of whom were German medics. A few minutes later the P-47s made their dramatic appearance and strafed the area, nipping the edges of both their lines.

Tired of such harassment, the Germans regrouped and at mid-afternoon launched their second attack straight down the bank of the canal. The frantic fight that followed was costly for the paratroopers. Mann was wounded two more times in his arms. Another man was hit at the base of his spine and died from loss of blood. One died when a shell fragment struck his head. Two men volunteered to break out and get aid; minutes later one returned wounded and reported the other had been captured.

The Lost Platoon

The German attack was driven off, but it left the detachment low on ammunition, high on casualties, and completely out of medical supplies. In spirit they still had a pulse, which was raised a bit late in the afternoon when two armored vehicles of XXX Corps appeared on the contested far side of the canal.

“Stay where you are. I am sure that help will be here soon,” advised the British commander.

At 5 pm, Chappuis launched his reorganized attack by 2nd Battalion from a different approach, this time to the southeast along the highway and not toward it like before. He was having better success, and by evening some pressure was lifted from Stopka inside the Zonsche Forest. German lines were beginning to show cracks, and their communications were eroding. Some of Chappuis’s men actually reached Wierzbowski’s outpost about midnight but did not stay for very long.

Wierzbowski told them the bridge was blown, and they took that information back to battalion. They failed to report, however, that Wierzbowski’s group, nursing its many wounds, was still holding on. In fact, word was spreading among the men that 2nd Platoon, now being called the lost platoon, had been wiped out.

A dense fog hid the destroyed bridge from Wierzbowski at first light on September 19, the third and final day of the battle at Best. Since the bridge was destroyed, so too was any urgency by regiment to advance on the position and relieve his unit. But it was not as if Chappuis and Stopka were sitting idle. They were fighting an increasingly strange and ferocious battle with enemy forces along the highway at Best and in the Zonsche Forest that had continued from the previous night.

Breaking the German Resistance

The stalemate continued with terrific fighting until late afternoon when a squadron of 12 British tanks from the 7th Armoured Regiment joined the attack and proved decisive.

“The rumbling of the tanks and the noise of their fire had taken all heart out of the enemy,” Stopka wrote in his report.

Demoralized German soldiers dropped their weapons and began to surrender in groups of 70 men at a time, 700 in two hours and about 1,200 total. They were rising out of ditches and emerging from woods, overwhelming the Americans still in combat attacking toward the canal. Neither side paid much attention to the other during the surrender.

Stopka radioed regiment to send all available MPs to assist. In the meantime, his staff assembled an assortment of cooks, messengers, and others to handle the prisoners until they arrived.

The tank-led attack pressed forward, crossed an open field strewn with dead Germans, and stopped at the canal south of Best. When the firing ceased, a disturbing element of the battle began to emerge and was confirmed by many eyewitnesses. Chappuis stated that on 10 different occasions he saw German soldiers walking toward American lines with arms raised in the air only to be shot dead from behind by German machine-gun crews. Stopka also watched the killing take place, and before dark sent a detail of men to the open field to assess the number of enemy dead. They counted 600 German bodies.

Joe Eugene Mann’s Medal of Honor

Wierzbowski, waiting in a shroud of mist at the former bridge site, was on his own for the duration. His men were exhausted, hurt, and content to wait for the relief that never arrived. As the sun rose higher in the sky that morning and temperatures warmed, the fog that covered the area burned off in an instant. When it did, a German officer suddenly appeared 20 feet away, leading a column of soldiers straight toward them.

The ensuing close-quarter fight was fast and furious. Grenades were thrown by both sides. Two rolled into foxholes, and both were tossed back before exploding. The next one landed in front of the machine gun, exploding in the face of Private Robert Laino, blowing out an eye and blinding the other, making a bloody pulp of his face. His cries for aid went unanswered. Another enemy grenade bounced off Laino’s knee. He dropped to the bottom of his foxhole, desperately trying to find it. Somehow he did, threw it back, and it exploded in mid air.

One of the last grenades thrown by the Germans rolled behind Mann, who was sitting inside a trench with six other wounded men. His arms were useless, wrapped tight to his torso by bandages to stop his four wounds from bleeding.

“I’m taking this one,” Mann said and pressed his back onto the grenade. The explosion split his backbone in half. “My back’s gone,” he whispered to Wierzbowski and died without a further sound.

Down to one grenade, the moment of surrender had arrived. On Wierzbowski’s order, Pfc. Anthony M. Waldt tied a handkerchief to the barrel of his rifle and waved it in the air. The fighting stopped, and 14 men crawled out of their foxholes and kept crawling toward their captors. Only three were unwounded.

Joe Eugene Mann was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for bravery and sacrifice on the battlefield that day. The 22-year-old native of Washington state was described as a “one-man army” by his comrades, who said he was the bravest man they had ever known. Mann is a national hero in Holland, the epitome of the American soldier. Children learn of his heroism in primary school, and two monuments stand in his honor, one located just off the A-2 Highway near the spot where he died. Cole and Mann, the only two Medal of Honor recipients from the 101st Airborne during World War II, died 24 hours apart at Best.

The German Surrender

After their surrender, Wierzbowski and his men were led behind German lines where they saw large numbers of enemy wounded needing medical help moving to the rear. Laino was bleeding too badly to continue when one of the German soldiers helped to bandage and carry the blinded man to their destination. They were dropped off on a mound of dirt guarded by two Germans when the same soldier who had dressed Laino’s wounds earlier returned from battle seriously shot in his shoulder. The paratroopers helped him as best they could and were finally moved to a German field hospital between the highway and Best, about 500 yards from the front. It was a busy and chaotic place with the high number of German casualties arriving, and the aid station staff became more excited when British tanks began their attack.

The Americans saw an opportunity and managed to disarm the few German guards on duty, capturing the hospital. They took nonessential Germans with them as prisoners; they agreed to go along willingly as long they remained prisoners of the Americans and not the British.

Wierzbowski’s small and valiant band crossed the highway and scurried into the 502nd lines while the German surrender was occurring, adding their own number to the bag of enemy soldiers captured that day. They had traversed a small circle in distance from their jumping off point in the Zonsche Forest two nights earlier but completed a long journey hard to match in daring, sacrifice, and commitment to duty.

Following the surrender of German troops on September 19, attacks on the 502nd lines diminished considerably overnight and into the next day. Best soon became unimportant in the greater conduct of the war and remained in German hands for another month, the Allies having a bigger problem to contend with trying to defend the wedge toward Arnhem created by Operation Market-Garden.

Tiny villages like Best can scarcely be found in Holland today, 70 years later, but one noteworthy event does occur in towns and cities all across the country every year. At 8 pm on May 4, the people of Holland dedicate two minutes of silence in recognition of the soldiers and civilians who died during their country’s four-year occupation by Nazi Germany.

Although familiar with operation Market Garden, I had not heard of this engagement at Best, Holland. I am both saddened by and proud of this small group of American paratroopers who withstood so well the consequences of this critical attack. Also saddened to discover the 600 or so surrenduring German soldiers killed by their own comrades. What a waste of warriors indeed! Although Market Garden failed, I know the operation had to be tried. Success in Holland in September 1944, may well have handed the allies victory. May we always remember, and always hold dear the sacrifices American service men and women have suffered in defense of freedom and democracy.

Years ago I used to go to a movie theater at Fort Campbell named in honor of Joe Mann. I never knew the story behind his CMH. Now I know.

My grandfather was wounded at bridge at best, his name is Vincent Laino. He was the one who had a grenade blow up in his face and then had another grenade hit his knee in which he collected and threw out if the foxhole before it exploded. The injury left with a metal plate in his head and a glass eye. He recieved a silver medal and a purple heart. He passed away in April 1977. He is our family’s hero.

there sacrifice gives us the freedom to be who we want to be and through this honour I adopted 2 grave at margraten the netherlands and the first grave is Alberto Garcia 101 airb engr 326 bn he died at the bridge at son en breugel , bless you who all served in the usa

My father was a Staff Sergeant in the 101st Airborne “B Company – 327th Glider Infantry Regiment” in WWII. He was in Holland, France, Belgium and Germany. When I was young, I didn’t listen to his “stories” like I should have. I just wasn’t interested as a kid. Now in my older age (59) I wish so much that I would’ve paid attention to what he was sharing with me. I had the good fortune of traveling to Holland in September 1994 with 101st Airborne family members to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of Holland. Let me tell you, the Hollanders are the most wonderful people on this earth!! They are so kind and caring and welcoming to Americans. Our buses drove down the small streets of Eindhoven and the Dutch citizens rushed out to the curb to wave American flags and to applaud and wave to “the American Liberators.” It was the most emotionally moving scene I’ve ever been a part of. There was more celebrating of America and Americans than we have here in the USA on the 4th of July. It was just incredible! Such wonderful and gracious, lovely people! Our family has maintained a lifelong friendship with several Dutch families that my father knew when he was in Holland during the war. The elders are all gone (including my father), but the children have remained in touch across the Atlantic. They are so grateful to America and to our military and they are truly such honorable people. Just had to share so all would know what truly wonderful people our Dutch friends are…