By Chuck Lyons

Able Seaman John Jeffcott, 27, of the HMS Jervis Bay was apprehensive in October 1940 as his ship sailed from Hailfax, Nova Scotia. She was escorting the convoy HX-84 as it headed toward the British Isles. A former London policeman, before the war Jeffcott had arrested a woman in London who claimed to be a fortune teller. Angry at the arrest, she had told him he would never live to see his 28th birthday.

In a week—on November 6, if he made it—he would turn 28.

As the convoy worked its way east across the frigid North Atlantic, Jeffcott’s feelings of dread increased, and with good reason. Between June and October 1940, more than 270 Allied ships had been sunk in the North Atlantic. Between May 1940 and July 1941 alone British ships went down at a rate of 66 a month, and German U-boats and surface raiders were hunting almost without opposition. Before the war was over, the British would lose 2,426 merchant ships and 19,180 seamen in the North Atlantic.

Jeffcott couldn’t know it then but in the six years of the war only one Victoria Cross was awarded for convoy duty. That VC was initiated by King George VI and awarded to Captain Edward Fegen, an Irishman whom Prime Minister Winston Churchill praised in the House of Commons, saying, “The spirit of the Royal Navy is exemplified in [his] forlorn and heroic action.”

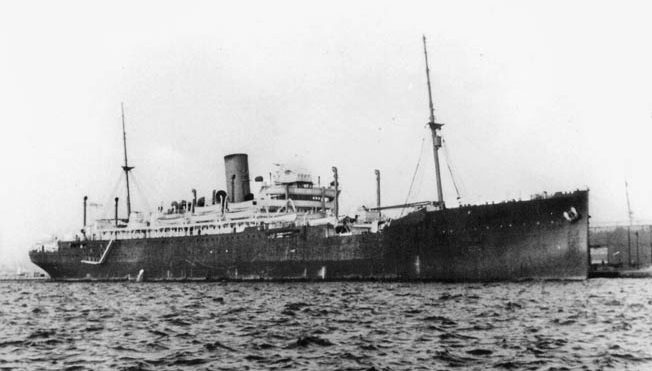

In October 1940 Captain Fegen was in command of the HMS Jervis Bay. The ship had been built by Vickers Unlimited, launched in 1922 as a steamer of the Aberdeen and Commonwealth Line, and taken over by the Royal Navy in August 1939, when it was converted to an armed merchant cruiser (AMC) and armed with seven 19th-century 6-inch guns and two 3-inch guns that were even older.

Lightly armed and riding high in the water, the ship became, as AMC crews called many of these ships, an “Admiralty-made coffin.” Fegen, who had been in the Royal Navy since early in World War I, was promoted to captain in March 1940 and assigned to command her.

Edward Fegen was born in 1891 in England of Irish parents, received a Silver Sea Gallantry Medal during World War I, and served in Australia between the wars, part of the time, ironically, at Jervis Bay on the south coast of New South Wales. In 1940, he was 49 years old.

If confronted by the enemy, Fegen told his officers when he came aboard, “I shall take you in as close as I possibly can.”

It was to prove a prophetic statement.

On October 28, 1940, Convoy HX-84 left Halifax under the watchful eye of the Jervis Bay. The following day the convoy was joined by nine ships from Nova Scotia and Bermuda, and the 38 merchantmen settled into formation—nine columns of four ranks each—to begin the crossing. Jervis Bay was positioned between the fourth and fifth ranks. As was routine, two Canadian destroyers accompanied the convoy briefly before turning back. When it approached Britain, the convoy would again be met by escort ships and planes, but for the 10 days of the passage the Jervis Bay and its antique guns would be its only protection.

Meanwhile, the Admiral Scheer was hunting in the North Atlantic.

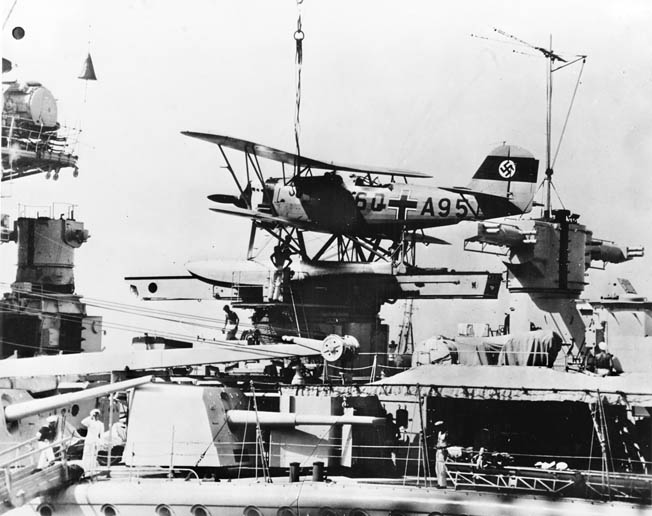

The Deutschland-class Admiral Scheer was a heavy cruiser—often called a pocket battleship—that had been launched in Wilhelmshaven in 1934. She had a top speed of 28 knots and was armed with six 11-inch guns in two triple-gun turrets, eight 6-inch guns, eight torpedoes, and antiaircraft guns. She had been deployed to Spain during the Spanish Civil War and then to the Atlantic when World War II broke out. By the end of the war in 1945, she had sunk 113,223 tons of shipping and would be considered the most successful surface raider of the war. She was feared by the men of the Atlantic convoys at least a much as—if not more than—the U-boat wolf packs.

Admiral Scheer was commanded by Captain Theodor Krancke who, like Fegen, had served in World War I and reamined in the German navy after that conflict. By the end of World War II, he had attained the rank of admiral and commanded all German naval forces in Western Europe.

Admiral Scheer had also sailed in October 1940. On that, her first combat sortie of the war, she slipped through the Denmark Strait and into the open Atlantic on the night of October 31. Once in the open sea, her radio intercept equipment quickly identified HX-84 in the area. Her seaplane then located the convoy on the morning of November 5 some 88 miles from the Scheer’s position.

The German ship headed in the convoy’s direction.

About 4 pm a lookout aboard the SS Rangitiki, the tallest of the convoy’s ships, noticed a mast on the horizon.

It was the Admiral Scheer. At 13,660 tons and 610 feet in length, she was nearly the same size as the 14,164-ton, 549-foot-long Jervis Bay.

Aboard Jervis Bay, Seaman Jeffcott, whose apprehension had continued to grow as his ship moved east, was only seven hours away from his 28th birthday.

Made aware of the Rangtiki’s sighting, at about 4:45 Captain Fegen sounded action stations and began accelerating his ship out of her convoy position and toward the Admiral Scheer.

Fegen immediately began firing his 6-inch guns even though he was well out of range of the Scheer. He also ordered smoke canisters deployed to hide the convoy, which made a quick turn away from the German ship and scattered. At a distance of about 10 miles, Captain Krancke swung the Scheer to port, bringing both his triple turrets to bear on the convoy and Jervis Bay. He began firing at the oncoming armed merchantman, the second salvo splashing 50 yards off Jervis Bay’s bow with 150-foot spouts of sea water, soaking the Bay’s forward gun crews.

Sam Patience, a quartermaster aboard Jervis Bay, heard what he later described as a “thunk” and turned to see a member of his gun crew slump to the deck, his head severed from his body. Admiral Scheer’s third salvo hit Jervis Bay’s bridge, knocking out her rangefinder, wireless, and fire-control equipment. Several officers and crewmen were killed by the blast, and Captain Fegen’s left arm was mangled.

As Scheer continued to fire, Jervis Bay was hit repeatedly on her superstructure, and her hull was holed in several places. The port bulkhead of the radio shack was gone and a radio operator and two coders were dead.

The remaining radioman climbed to the remnants of the bridge where he saw Captain Fegen“clutching his arm, blood spilling off his sleeve.”

Fires burned uncontrolled.

Wanting to neutralize the escort ship so he was free to attack the convoy, Scheer’s commander continued to train his big guns on Jervis Bay. Darkness was falling, and he knew he needed to sink Jervis Bay quickly so that he would have time to attack the convoy. Each salvo from the Scheer launched two and a half tons of ordnance at the stricken ship. The forward port side of Jervis caught the brunt of the fire and became a mass of twisted girders, bent and jagged plate, dead and wounded sailors, and flames. A shell somehow loosed Jervis’s anchor, and another knocked the white ensign of the Royal Navy off the top of the main mast. Midshipman Ronald Butler later recalled helping an unnamed seaman climb the mast to nail up a replacement ensign.

Jervis Bay continued steaming at Admiral Scheer and firing her guns until her steering gear was knocked out. The petty officer manning the wheel called into the voice tube that the ship’s steering gear was out of action and heard the captain’s pained voice come back ordering him to “man the aft steering position.”

With his ship aflame and sinking, Captain Fegen continued to maintain the unequal fight and stayed in command despite his shattered arm, consciously buying time for the ships of the convoy to escape.

Up to now, Captain Fegen had stayed on the collapsing bridge, which was under continuous hits from Admiral Scheer’s big guns. Shortly after giving the order to man the aft gear, however, he struggled down the starboard side of the bridge and, aided by a signalman, headed aft, stopping to encourage a gunner along the way and ordering more smoke deployed.

After a blast destroyed the after-control compartment just as he arrived there, the captain headed forward again, with “blood running over the four gold stripes on his sleeve,” Midshipman Butler later said.

Captain Fegen never made it. His body and the body of the signalman who was helping him were later seen on the deck. “[Jervis Bay] did not have a chance, and we all knew it,” said Captain Sven Olander, commander of the Swedish freighter Stureholm, one of the convoy ships. “But she rode like a hero and stayed to the last.”

Meanwhile, exploding cordite bags on Jervis Bay’s poop deck had convinced Captain Krancke that the smaller ship was still firing despite the severe damage she had suffered. He didn’t dare concentrate on the convoy until the threat posed by Jervis Bay was eliminated. Any damage to his ship from a lucky hit could seriously affect her ability to escape any hunt for her launched by the Royal Navy.

Krancke continued focusing his big guns on Jervis Bay, but turned some of his smaller ones against ships in the convoy that were still within his range.

After an hour of the unrelenting German fire and with Captain Fegen dead, Lt. Cmdr. George Roe, now in command, ordered the remaining crew of Jervis Bay to abandon ship. All of Jervis Bay’s life boats had been destroyed but rafts, some of which were damaged, and the ship’s 18-foot “jolly boat” had survived the bombardment and were launched. Most of Jervis Bay’s men simply jumped into the icy, sub-Arctic sea, some making it to the rafts and jolly boat. Others made do with what they could find floating in the water.

Shortly after the order was given to abandon ship, Jervis Bay went down. The white ensign Midshipman Butler had helped raise was the last thing to settle beneath the Atlantic waves.

Standard convoy orders were to keep going if attacked; it was too dangerous to stop for survivors. But Captain Olander of the Stureholm, impressed by the courage shown by Captain Fegen and Jervis Bay, called his ship’s crew together and proposed they return to the scene and pick up survivors.

“She … gave us a chance to run for it,” he said. “Now I would like to go back and see if there is anyone still in the water.”

The men of the Swedish ship agreed, and the freighter returned back to the battle scene where it was able to pull 68 men of Jervis Bay’s crew of 266 from the sea, three of whom died after being rescued and were committed to the deep that night. Stureholm then returned to Halifax, which she considered the safer of her options, arriving there on November 12.

With Jervis Bay taken care of, Admiral Scheer turned her attention to the ships of the convoy, which had taken advantage of the time Jervis Bay had bought for them to scatter. Scheer continued searching for the scattered convoy ships and was able to sink six.

Five quickly assembled Royal Navy battle groups consisting of two battleships, three battle cruisers, an aircraft carrier, five cruisers, and 15 destroyers hastened to the area. The battle groups spent two weeks unsuccessfully searching for the Admiral Scheer. In addition to her kills in the convoy, Admiral Scheer had been able to pull a number of British ships from regular operations—another of her objectives. She continued into the South Atlantic and then the Indian Ocean, sinking or capturing an additional 10 cargo ships before her cruise ended in the spring of 1941.

The war ended for Admiral Scheer in April 1945 when she capsized in about 50 feet of water during a 300-plane air raid at Kiel on the southwestern coast of the Baltic Sea. After the war she was stripped by the British, covered with rubble, and turned into the foundation of a new quay.

Fegen was recommended for the Victoria Cross by Britain’s King George VI, who was said to be “stirred deeply” by Fegen’s sacrifice. The medal was awarded to Fegen’s sister at Buckingham Palace in June 1941.

“When [Captain Fegen] attacked the Admiral Scheer,” the King wrote in his diary, “he knew he was going to certain death.”

Seaman Jeffcott, who was haunted by the fortune teller’s prediction, also died that night, the eve of his 28th birthday. He was killed either in the bombardment of HMS Jervis Bay or in the frigid North Atlantic water that claimed her. Jeffcott was listed as “lost at sea,” one of thousands of British sailors whose only grave is the ocean.

Thank you very much for remembering all the sailors who fought so hard and saved so many. It is a sad event but one of bravery. My dad (George Lamont Osborne Beaman) was aboard and was a survivor. While he didn’t talk about the event I could tell he thought of it often. I was not born at that time but when I was old enough to understand, I would often see him stare off into the distance for long periods but he did not wish to talk about it.

Bless all those families associated with this tragedy, especially with November 5 approaching.

Thank you again for remembering this event and all the brave sailors. I’m glad I found this site.

G Marion Warren (Beaman)

Dear Marion,

And all who are aware of the story of the HMS JERVIS BAY. My Grandfather was a rivet boy working on the conversion of the Jervis Bay to a merchant cruiser, He had a life long love of the vessel there after. I was brought up with the story of the heroic sacrifice made by Capt Fegan and the crew and coming from a family of merchant seamen ,and living within walking distance of the once great London docks ,the Jervis Bay has been a large part off my upbringing. Last year my Fiancee and I married in Sherborne Abbey Dorset,England, the first Hymn played at our service was FOR THOSE IN PERIL ON THE SEA, we dedicated it to Capt Feegan and the crew of The Jervis Bay, we also had the Merchant Flag flown over the Abbey.I was due to visit the Merchant Seaman memorial Gardens today, the 5 thof November to lay a wreath and honour these brave souls, but the lockdown restrictions have put pay to those plans. Instead I have laid the wreath in my garden in the centre of which I have placed a candle that I will light at 1700 hrs to burn through the night in memory of those brave and selfless individuals who gave so much, and suffered so profoundly in service of their Country. May God Bless them All.

Daryl Young,

Essex ,England .

My Grandfather, Stoker of the HMS Jervis Bay, George Lamont Osborne Beaman.. we will remember

My grandfather Robert (Bob) Hill served on the Jervis Bay, he was left behind in Canada following earlier injury and infection costing him a lung, which subsequently cost him his service career. He told me the story of the Jervis Bay, he was very proud of his colleagues and their heroism, he was always sad when he talked about it, as where he worked in the ship none of his friends survived the engagement. I have just been viewing this page with my daughter, his great grand daughter and telling her the story of the Jervis Bay.

Thank you for recording the events leading to the sinking of the Jervis Bay. I was pleased to be able to read of the heroic stand of the Captain and crew. Some years ago, my father wrote a memoir of past family members and mentioned his cousin Daisy Cozins. She had married Dennis People who was crew on the ship and perished drowned on the fateful day the Jervis Bay was sunk in November 1940.

From Canberra Australia.

The Royal Australian Navy has been proud to commission two vessels named HMAS Jervis Bay

Details are here: https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-jervis-bay-i and here https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-jervis-bay-ii

The service history of Captain Fegan usually only refers to his service in Australia, between 1928 and 1929. His position was as Commanding Officer of HMAS Creswell – the training college where our naval officers complete their training prior to being posted. https://www.navyhistory.org.au/tag/hms-jervis-bay/

If you read the last tag, you’ll find the Royal Australian Navy continues to commemorate and honour the memory of Captain Fogarty Fegen VC.

My mother migrated to Australia from the UK on board the SS Jervis Bay in September 1930.

From time to time I lay some flowers on our local war memorial on 5 November with a short note explaining they are for the crew of HMS Jervis Bay.

It’s the most courageous story I’ve ever read and we should remember it.

Thank you for this memorial to the sacrifices of the officers and men on the HMS Jervis Bay. My grandfather Leading Seaman John A. Blyth was one of those who gave their lives during this gallant, but decidedly one-sided, battle. My grandmother, Jessie E. Blyth never remarried and raised both of their children, Valerie and Raymond, in their Kings Lynn, Norfolk cottage.

My uncle’s brother, Victor Boyland, able seaman, was one of those lost on that ship. As a boy he would sometimes tell me that story.

But for the actions of the ship most of that convoy would have probably been sunk.

My great uncle, Lieutenant Arnold Bartle was lost at sea. I’m in awe of the bravery of these men. God rest their souls.

I’m so glad that I have this memorial to reflect and remember those lost on The Jervis Bay.

With regard to “Bay Ships” and convoy duty. I have a picture taken at Sierra Leone from the deck of the HMAS later HMS Moreton Bay. My father had jotted down some notes… saying: Here we are the Moreton Bay, out front of 55 ships heading out in the Atlantic, on our way to UK. He mentioned they were the decoy ship. (Fodder for U-Boats) my words. I wrote to UK authorities some 4o – 45 years ago. They denied any knowledge of decoy appointments. Maybe the secrets acts have been relaxed now. Dad was told that was their duty. He was with the ship for many years. He did his training on board the ship sailing thru Sydney Heads September. 1939. He ended up back in Australia at Garden Island. The ship was later scrapped.

My uncle, Able Seaman Michael McNamara, was among those lost in this unequal battle. I have just sent this account of the heroism of the Jervis Bay’s crew to my young grandchildren so they might know about the courage shown and sacrifice made by their great uncle.

We will remember.

I first read the story of the heroic actions of the Captain and Crew of the Jervis Bay, when I was a child. This battle epitomised the values of duty before self, which made Britain and its Commonwealth such a formidable force during the two World Wars.

The awesome courage and sacrifice so impressed the Captain, Sven Olander and crew of the Swedish ship Stureholm, that they unanimously agreed to go back and search for survivors. The quiet courage, gratitude and kindness of these civilian sailors is almost beyond belief.

I have a charming lamp that has an engraved plate “HMS Jervis Bay” which has been in my family since late ’40s. On the underside is a sticker describing “Legend of HMS Jervis Bay” . If someone in your organization is interested in having the lamp I would be happy to find a way to ship it. I am near Toronto, Canada. Please email me directly and I will send photos.

Dear Stella,

I am writing in response to the message you posted yesterday. You will may have seen the message I posted at the top of this page on the 5th of November 2020, my name is Daryl Young. As you will see from my message, the story of Jervis Bay was an integral part of my upbringing. My Grandfather, who was an integral part of my formative years was for ever entwinned with the vessel. We lived in the East End of London, directly opposite the Royal Albert dock, merchant vessels, were part of our family and all of my family sailed in the merchant fleet. Should you wish for your lamp to be homed here, I would be honoured to place it in my cabinet displaying military artefacts dedicated to those that paid the supreme sacrifice on our behalf. However I would insist that this comes at no cost to your goodself and would reimburse you for postage etc. Our two Countries share a history, a patronage, a that is sadly being lost. The annual Remembrance Day parade on the 11th of November is no longer the national heartfelt commemoration it once was, and the passage of time, the loss of a generation, and the burn of the sacrifices made are slipping into the history books. I am 52 this year, my generation were brought up by people for whom the war was real, tangible, and costly. The people behind my generation have no concept of the sacrifice, neither do they care sadly. We have had two occasions here in recent times where the Cenotaph in Westminster has been desecrated during riots. Such despicable acts of treachery would have been totally unthinkable just a few years ago. Some 4 years ago now my Wife, Lynsie and I visited the Greek Island of Crete. Whilst there we visited the Suda Bay Cemetery to lay a wreath in honour of an elderly friend of mine who was taken POW from there in 1941. He survived the camps and the war, but died at the grand old age of 93. I always promised Him that I would visit Suda Bay one day and lay a wreath for His friends that didnt make it, we did so and was very honoured to do so. Whilst we were there, we noted that there were many names of young Canadian Airmen who gave their all, we laid the wreath in honour of those poor souls as well.

Kind Regards, Daryl Young

I have included a link to another well-maintained site that memorializes the Jervis Bay and her crew.

Let’s try adding the url again…

https://hmsjervisbay.com/Today.MemorialsJB.php

My mother’s brother….my uncle, Wilson Avery from Long Beach, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland was a gunner on the Jervis Bay & lost his life that Nov. 5th. He was only 23 years old.