By Flint Whitlock

After overrunning France and other Western European countries in 1940, Adolf Hitler was certain that the Allies would one day attempt to invade the European continent and attack through the occupied countries to destroy his regime. He just didn’t know when or where.

To forestall an invasion, he ordered the construction of the world’s second largest fortified barrier, second only to the 5,500-mile-long Great Wall of China. Hitler decreed that his so-called “Atlantic Wall” would stretch along the coast from northern Norway to France’s border with Spain—2,400 miles in length.

Frederick the Great’s military maxim holds, “He who defends everything defends nothing.” This maxim was unknown to—or at least disregarded by—Hitler, whose goal was to so completely seal off his western coastal flank that the Allies would be dissuaded from attempting an invasion.

Money for such an ambitious, enormous project was no object to the Nazi regime; the only problem was one of time. While China’s Great Wall took centuries to build, Hitler knew he did not have such luxury.

The French coastline, from the border with Spain in the south to the border with Belgium in the north, was considered by Hitler and the German high command as the most likely place the Allies would invade. In this regard, the English Channel port city of Calais, in Upper Normandy, was deemed the most likely invasion site given its close proximity (20 miles) to southeastern England. Indeed, Calais was the place from which Germany planned to launch Operation Sea Lion in 1940—before Hitler called off the invasion and decided instead to attack the Soviet Union in 1941.

Hitler entrusted his idea of creating an impenetrable wall to the one man whose organization he knew was capable of pulling it off: Dr. Fritz Todt.

Born in 1891, Todt studied engineering in Karlsruhe and at Munich’s School for Advanced Technical Studies, then served in the Kaiser’s army when the Great War broke out, earning the Iron Cross. After the armistice, Todt continued his education, earning his doctorate in engineering. Todt was impressed by the young firebrand Hitler and his plans for a new, revitalized Germany and eagerly joined the Nazi Party in 1922, and later the SA and SS.

In 1925, Todt became head of engineering for the Munich civil engineering firm of Sager and Woerner, which specialized in building roads and tunnels. The 39-year-old Todt came to the future Führer’s attention in 1930 when he published a paper titled “Proposals and Financial Plans for the Employment of One Million Men.”

This was just the kind of thinking that Hitler needed to help pull Germany, which had been especially hard hit by the worldwide economic depression, out of its doldrums. Todt’s vision of a giant public works program, the building of a nationwide system of high-speed highways known as the Autobahn, would put Germans back to work on a large scale. And so, in 1933, shortly after becoming chancellor, Hitler appointed Todt to head a new, state-owned corporation—Organization Todt (OT)—that would create the roadway network.

After the Autobahn system became a dramatic success, Hitler began thinking of creating a static defensive system on the order of France’s Maginot Line. In 1936, knowing that his buildup of Germany’s armed forces would likely result in war, Hitler directed Todt to join together Organization Todt, private companies, and the Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD) to begin constructing a string of fortifications along Germany’s western border that would become known as the Westwall (called the Siegfried Line by the Allies).

In March 1940, with Germany now at war, Hitler appointed Todt Reich Minister for Weapons and Munitions; in 1941, the duties of General Inspector for Roads, Water, and Energy were added to Todt’s growing plate of responsibilities. Onto this plate was soon heaped the creation of the Atlantic Wall.

Curiously, work on an anti-invasion coastal barrier did not get off to a fast start. Instead, in 1940-1941, construction efforts were focused on building bombproof U-boat pens along the French coast at places such as St. Nazaire, La Rochelle, and Lorient.

But, on December 14, 1941, with worry growing about British attempts to penetrate the German-occupied coast, Hitler ordered that efforts to fortify the shoreline be stepped up. Four months later, in March 1942, after British commandos had snuck ashore at Bruneval, France, and stolen top secret radar equipment, Hitler, fearing more commando raids, demanded that work on an adequate defense be accelerated, beginning with Norway and the Channel Islands to the west of the Cherbourg Peninsula.

Also, in March 1942, Führer Directive No. 40 was issued that pitted the services against each other. Hitler specified that the navy and air force were to have the primary responsibility for costal defense; the army would become involved only in the case of an actual enemy landing. Army commanders felt slighted when the navy received a larger allocation of concrete for the construction of its positions.

In May 1942, following another devastating British commando raid, this time on the St. Nazaire naval base on March 28 (Operation Chariot), Hitler again emphasized the need to finish the Atlantic Wall. By that time, however, Fritz Todt was dead (ironically, in German, the word “todt” means “dead”), having been killed when his plane mysteriously exploded on February 8, 1942, shortly after taking off from Rastenburg in East Prussia after he left a conference with Hitler.

The cause of the explosion was never decisively determined, but suspicion still centers around either Hermann Göring or Martin Bormann, who it is said were unhappy with Todt’s growing influence with Hitler. Although Albert Speer succeeded Todt as Minister of Armaments and nominal head of Organisation Todt, OT was actually run by Franz X. Dorsch, his deputy.

Under Speer, work on the Atlantic Wall shifted into high gear in June 1942, with particular emphasis on fortifying port facilities to prevent an Allied invasion fleet from using them.

In August 1942, Hitler, aware of his combat manpower limitations, declared, “There is only one battle front (the Russian Front). The other fronts can only be defended with modest forces…. During the winter, with fanatical zeal, a fortress must be built which will hold in all circumstances … except by an attack lasting several weeks.”

Building a Bunker

The scope of the Atlantic Wall project was vast. In France alone, millions of cubic meters of earth were displaced by pick, shovel, and machine during the creation of the wall. Some 17 million cubic meters of concrete were poured, and 1.2 million tons of steel—representing five percent of Germany’s total annual steel production—were used for everything from reinforcing bars (rebar) to bunker doors to gun platforms.

OT created numerous standard designs of casemates, bunkers, and other defensive works, labeled Types 134, 272, 501, 622, 669, 677, 683, etc., many borrowed from Westwall designs. Each design could be modified to fit the terrain or special tactical circumstances. And, since there were four different service commands in Normandy, not all under army authority, there were modifications for these as well. For example, the Type 677 might be appended with an “H” (for Heer, or army), an “M” (for Marine, or navy), or “L” (for Luftwaffe, or air force).

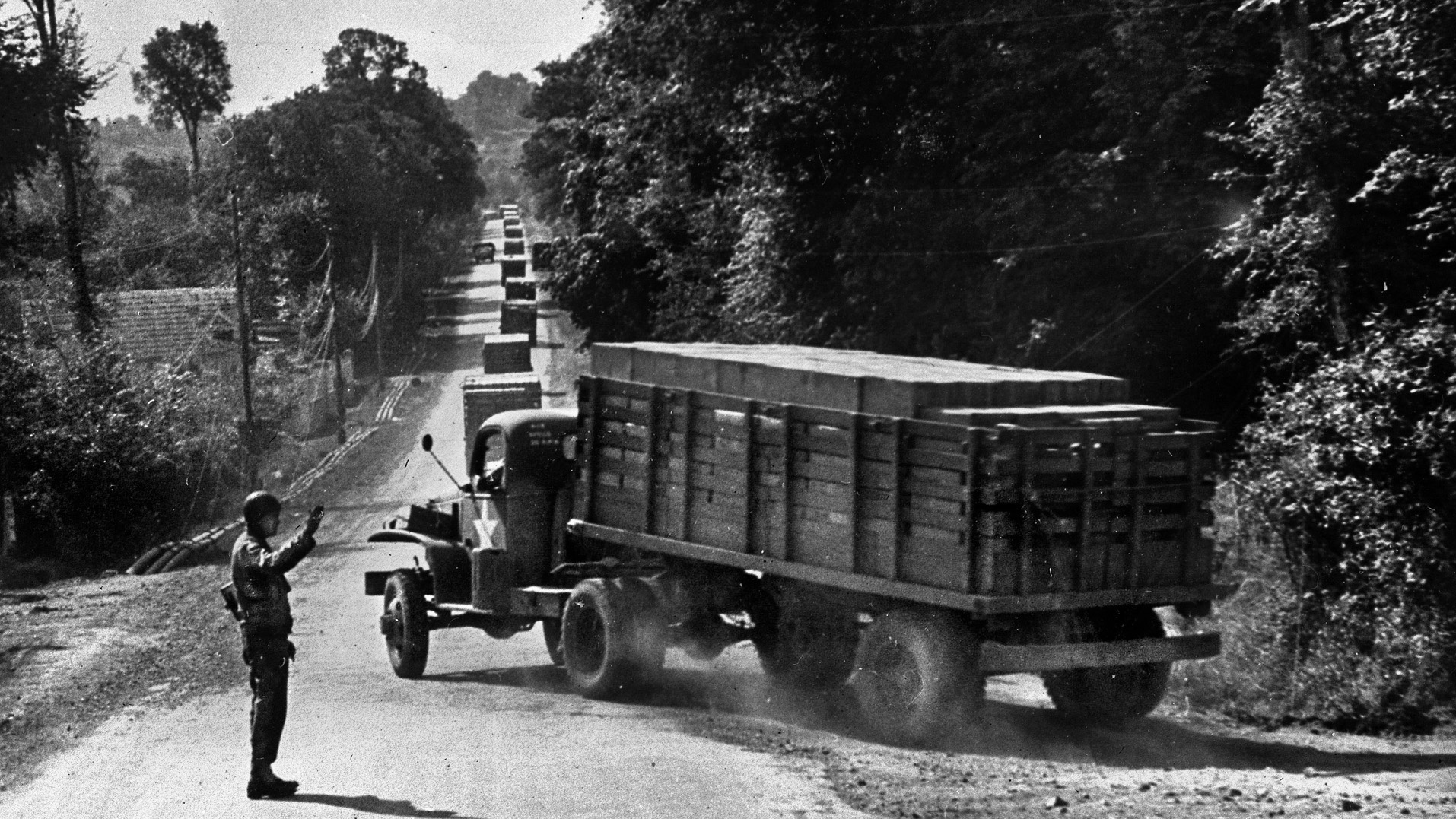

Tens of thousands of workers were needed for a project of this magnitude. They came from OT itself, from the Reichsarbeitsdienst, army, navy, and air force, plus foreign nationals from the occupied countries, and from private French and German construction firms. Another source of labor was free: prisoners of war and men from the concentration camps. Just before the Normandy invasion, OT was using some 286,000 workmen who toiled anonymously for years on the Atlantic Wall project.

Rene-Georges Lubat, 91, one of the few Frenchmen still alive who worked on the Wall, said that in 1942 he was “volunteered” by his village mayor and sent to work on defenses in the Arcachon (southwest France) sector. “There was no choice about it. We had to go,” he said. “Naturally we weren’t enthusiastic, but it is not as if we had any choice.

“The conditions were not terrible. We weren’t beaten or anything, and we got a basic wage. At the start, we could go home on Sundays, but after [the German defeat at] Stalingrad, they put up barbed wire and we were stuck inside the work camp. Of course we knew we were building defenses for the Germans, and it felt bad.”

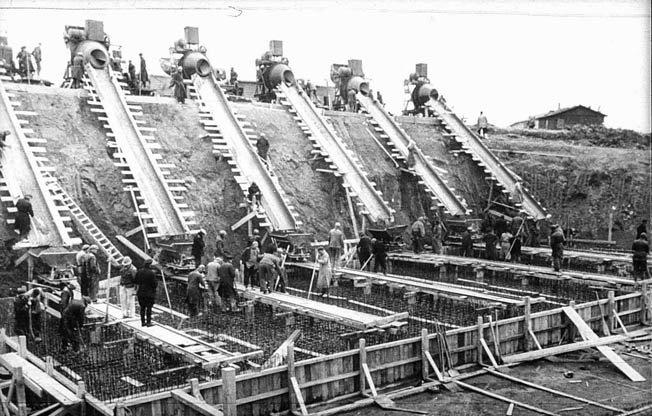

Constructing the mammoth concrete structures was, in itself, no easy task. First the sites had to be selected and the ground prepared by removing foliage, tons of earth, and any already existing structures. A sub-base consisting of compacted stones and pebbles then had to be added, surrounded by wooden forms. Huge cement mixers were brought in and, after a grid of steel rebar was laid on top of the subbase, the floor was poured and smoothed flat with hand tools. In numerous cases, there were tunnels and subterranean rooms extending many meters below ground level.

Once the floor had hardened (cured), more wooden forms, or shuttering, were erected as molds so that the walls could be poured and held in place until the concrete dried. Into the footings of the walls, vertical steel rebar was set. Before the roof was poured, steel I-beams were placed horizontally to give it more strength against shells detonating on or above the roof. In many instances, a large-caliber artillery piece (often a large-bore naval gun) was installed by crane before the concrete roof and rear walls were built.

In many cases, all four walls of a casemate were poured, although in some (quite visible at Pointe du Hoc) the “backs” of the casemates (i.e., facing away from the direction of expected enemy fire) were made from large concrete blocks.

Once the casemate was finished, fill dirt was piled up around the structure to help it blend into the landscape, grass and foliage were added to help conceal it, and camouflage netting was draped over it to further hide it from prying eyes. It took from six months to a year to build and get most of the heavy batteries operational.

Contrary to popular belief, not all the bunkers were gun positions—massive concrete blockhouses that contained huge artillery pieces taken from battleships and cruisers. Crews manning the combat bunkers also needed fortified sleeping quarters, mess halls, trenches, water reservoirs, medical facilities, electrical generation, ammunition storage, command, communication, and observation bunkers, so these were also built.

There were open-top platforms for antiaircraft guns, radar and searchlight stands, mortars, and machine guns. Some fighting positions were merely a tank turret set into a concrete emplacement, while others were one- and two-man concrete foxholes known as Tobruks (so named because they had first been used in the 240-day siege of the Libyan fortress city of Tobruk in 1941).

Augmenting the fixed bunkers in France were 13 railway guns firing everything from 150mm to 380mm shells, the larger guns mounted on carriages that allowed them to be rolled out of a camouflaged shelter, fired, and then rolled back into their hiding places, safe from Allied aircraft.

All told, there were more than 1,300 guns of 100mm caliber or larger along the French coast in scores of casemates; more than half of these were 105mm and 155mm.

Day and night, seven days a week, all along the French coastline trucks filled the roads with building materials and giant cement mixers noisily ground on, along with the popping sounds of welders. The shouts of OT foremen filled the air along with the crack of whips on the backs of slave laborers who did not work fast enough. Despite Hitler’s calls for maximum effort to complete the defenses as quickly as possible, time was not on Germany’s side.

Of course, all the heavy construction activity going on could not take place in secret. Although ordinary civilians were banned from the work areas, members of the French Resistance managed to penetrate or work in the construction sites and pass information along to the Allies so they could pinpoint these targets.

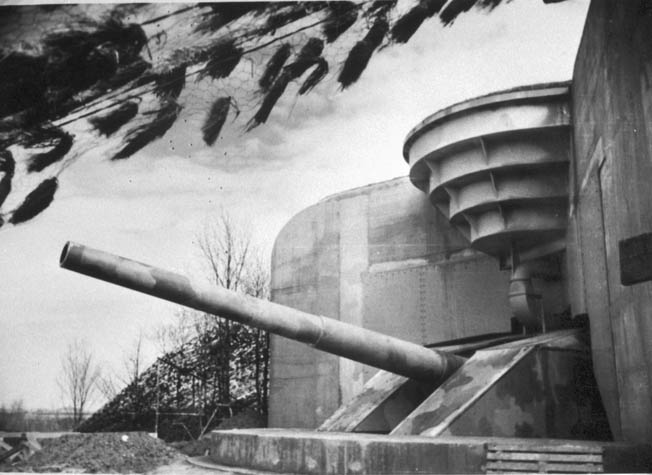

An excellent example of a casemated battery is Battery Todt, built in 1940 near Audinghen, between Calais and Boulogne. Originally called Battery Siegfried, the name was changed to honor Fritz Todt after his death.

These four massive casemates, which housed long-range 380mm (15-inch) guns, had more of an offensive than a defensive mission. Their main purpose was to harass Allied ships in the Channel, bombard air bases, military camps, and other installations in Kent, and play havoc with any invasion fleet that might venture across the Straits of Dover.

The British also had several large-caliber, long-range, casemated batteries in Dover, installed in anticipation of the German invasion in 1940. From time to time they dueled with the German batteries across the Channel.

In the event that enemy forces tried to attack them, the main German batteries such as Todt and Lindemann had their own defensive systems, including antiaircraft guns, machine-gun positions, barbed wire, antitank ditches, and minefields.

Battery Lindemann, named for the captain of the battleship Bismarck who went down with his ship in May 1941, was located near Sangatte and was the largest battery in France. The three casemates (named Anton, Bruno, and Caesar), each of which housed a 406mm (16-inch) naval gun, had walls up to 13 feet thick, ammunition storage, and integrated crew quarters with all the comforts of home.

The bunkers, however, were anything but comfortable. The thick concrete walls made the interiors chilly even in summer, and the Channel winds blew in steadily through the large gun apertures.

For the gunners in these big bunkers, employing large-caliber guns that had been taken from battleships or cruisers, the same problems that confronted naval gun crews confronted them—the deafening blasts and the danger of flash burns when the guns were fired. For these crews, ear protection and protective clothing were issued.

Add these conditions to the generally isolated positions and the uncertainty as to when, where, or whether the Allies would attack must have made static duty in the bunkers rather boring and unpleasant.

A Shift in Focus

Although U.S. and British forces were still bottled up in the mountains of Italy, Hitler, on November 3, 1943, shifted his focus from the Eastern Front to the West and looked toward the future. He issued Führer Directive No. 51, which stated in part, “In the East, as a last resort, the vastness of the space will permit the loss of territory even on a major scale without suffering a mortal blow to Germany’s chance for survival.

“Not so in the West! If the enemy here succeeds in penetrating our defenses on a wide front, consequences of staggering proportions will follow immediately. All signs point to an offensive against the Western Front of Europe no later than spring [1944], and perhaps earlier. For that reason, I can no longer justify the further weakening of the West in favor of other theaters of war. I have therefore decided to strengthen the defenses in the West.”

With Hitler and most of his commanders and ministers convinced that the Allies would use the shortest route across the Straits of Dover to invade the Continent, OT was ordered to shift the bulk of its efforts to beef up defensive works in the Pas de Calais area.

For his part, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels did much to tout the strength and immensity of the still unfinished fortifications. Through newspaper and magazine articles, newsreels, and images of massive concrete bunkers, with huge naval gun barrels poking out menacingly from their embrasures, Goebbels hoped to convince the Allies that attempting an attack against such obviously well-prepared coastal defenses would be suicidal.

But General Hans von Salmuth, commander of the Fifteenth Army in Normandy, was not impressed. “The Atlantic Wall is no wall!!!” he wrote scathingly to his superiors in Berlin in the autumn of 1943. “Rather it is like a thin and fragile cord which has a few small knots at isolated places such as Dieppe and Dunkirk. The strengthening of this cord was no doubt underway during the past spring and summer. Since August the effort has been getting steadily weaker … and any considerable increase in bunker construction will not take place till spring [since] material and labor are lacking.”

From Desert Fox to Normandy Defender

Still recovering from a debilitating illness that necessitated his being relieved from command in North Africa, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was personally appointed by Hitler in late 1943 to head Army Group B (France, Holland, and Belgium); Hitler also put the wily Desert Fox in charge of speeding up construction of the Atlantic Wall, sending him on a trip to inspect the incomplete defenses and make recommendations on what needed to be done.

Rommel was appalled by what he found. While Goebbels had been beating the propaganda drum in hopes of frightening the Allies into thinking the wall was more formidable than it actually was, Rommel was learning that the wall, in most places, was paper thin. The Wall, Rommel wrote in secret to a confidant, was nothing more than “a figment of Hitler’s cloud-cuckoo-land … an enormous bluff … more for the German people than for the enemy.”

In addition to the slow pace of construction and the lack of a defense in depth, Rommel knew that the Allies were building up a huge invasion force across the English Channel that would charge across the waves and skies in the very near future. He whipped his subordinate commanders into a frenzy of activity to complete the bunkers, the minefields, and the beach defenses.

As Rommel told Hitler on December 31, 1943, after his inspection tour, “The focus of the enemy landing operation will probably be directed against Fifteenth Army’s sector [the Pas de Calais]…. [I]t is likely that the enemy’s main concern will be to get the quickest possible possession of a port or ports capable of handling large ships.”

Rommel was obviously unaware that the Allies, correctly assuming that the Germans would destroy port facilities in France and Belgium before they fell into Allied hands, were building artificial harbors in Britain—codenamed Mulberries and Gooseberries—and would tow them across the Channel.

“Furthermore,” Rommel continued, “it is most likely that the enemy … will make his main effort against the sector between Boulogne and the Somme estuary and on either side of Calais, where he would have the shortest sea-route for the assault and for bringing up supplies, and the most favorable conditions for the use of his air arm.

“As for his airborne forces, we can expect him to use the bulk of them to open up our coastal front from the rear and take quick possession of the area from which our long-range missiles [i.e., the V-1 and V-2 rockets] will be coming.”

No detail was too insignificant to catch Rommel’s critical eye. At one point less than a month before the invasion, Rommel was checking on the status of construction at La Madeleine, a place the Americans had marked as Utah Beach on their top-secret invasion maps. He came across Lieutenant Arthur Jahnke, who had been wounded on the Eastern Front and who was in command of a company working to stiffen the defenses there. Rommel was unhappy; there were not enough mines, not enough barbed wire, not enough beach obstacles.

“Let’s see your hands, Leutnant,” Rommel growled. When he saw that Jahnke’s hands were just as calloused and scarred by physical labor as his men’s, he relented a bit.

“Very well, Leutnant. The blood you lost building the fortifications is as precious as what you shed in combat.”

To an impartial observer, the hundreds of concrete and steel blockhouses and casemates that had already been built or were still in various stages of completion—along with the mile after mile of coastline bristling with barbed wire, mines, and a fiendish variety of obstacles, not to mention the monstrous, large-caliber guns—looked as if Rommel had accomplished the impossible. He had managed, it seemed, to fortify an entire coastline well enough to prevent or at least inhibit an invading force from gaining a foothold in occupied France.

Rommel, of course, would disagree with that assessment. Each day, as he started out on his inspection tours in his big, open-top Horch staff car from his headquarters at La Roche-Guyon, 70 miles away from the nearest coastal installation (Dieppe), he would chew out the construction teams for not working fast and hard enough. Sensing that the invasion was imminent, he made constant phone calls and wrote dozens of letters back to Berlin, complaining about the shortages of concrete, rebar, cement mixers, men, and more.

Although there was still much to do, much had been accomplished in an incredibly short amount of time. Some four million mines had been sown, and thousands of miles of barbed wire had been strung. Hundreds of bunkers, casemates, and fighting positions had been emplaced (6,000 in France alone).

Guarding the approaches to the mouth of the Seine Estuary at Le Havre were casemated batteries at Vasouy, Villerville, Ste. Adresse, and Mont Canisy. Other bunkered batteries, such as the ones at Le Portel, La Trésorerie, Herquelingue, Wimereux, and Mont Lambert, protected the fortified port of Boulogne-sur-Mer.

South of Boulogne were batteries at St. Cecile-Plage, Hardelot, Le Touquet, and Le Treport. Still more ranged for hundreds of miles along the coast between Le Havre and Dunkirk; there was an average of one battery (usually four guns) every 17 miles. So well defended was the area around Calais that it became known as “the Iron Coast.”

A six-gun battery sat atop Pointe-du-Hoc, where it had a commanding view of the Channel and beaches to both the east and west—beaches that would soon be known to the world as Utah and Omaha.

Under Rommel’s tireless leadership, the coastal defenses were greatly expanded, comprising everything from thick minefields to beach and underwater obstacles (tetrahedrons, Belgian Gates, concrete stakes, and slanted logs topped with mines) to antiglider poles known as “Rommel’s Asparagus” that would break up gliders when they landed behind the coast.

Many bunkers that were visible from the sea were camouflaged to look like civilian houses and shops, complete with painted signs, windows, and fake roofs. The largest casemates, such as those at Battery Todt, had camouflage netting draped over them to help them blend into the landscape along with heavy chains hanging down over their gun embrasures as a way of preventing enemy shells and/or splinters from flying directly into the large openings.

Hitler sometimes suggested ideas for the Atlantic Wall, conceiving a weapon that he felt would further create fear in the Allied camp. “Can’t we arrange for a special allocation of flame-throwers for the West?” he asked his cronies. “Flame-throwers are the best thing for the defense; after all, they are terrifying weapons…. [Speer] has workers available…. You could … have them make flame-throwers. Especially in defense, the flame-thrower is the most terrifying thing there is.

“That will take the pluck out of the attacking infantry, I should say, before it starts hand-to-hand fighting. It will lose its pluck when it suddenly gets the feeling that there are flame-throwers on all sides. Also in battery positions there must be flame-throwers. Everywhere there should be flame-throwers.”

Despite Hitler’s fervent belief in fire-spewing weapons, the only flamethrowers used during the Normandy invasion were those carried by some American infantrymen in the assault waves.

The German fortification efforts began to face serious manpower shortages in 1943 as many of the workers engaged in the Atlantic Wall project were transferred to Germany and the occupied countries to repair the damage inflicted by Allied bombing. Additionally, in 1943, fortifying German and Italian positions became a priority in Sicily, Italy, and throughout the Mediterranean area, which further stretched the Reich’s resources to the limit.

Lieutenant General Fritz Bayerlein, Rommel’s former acting chief of staff in North Africa and still a close friend and confidant, wrote that Rommel once told him that despite Soviet advances on the Eastern Front, “The West is the place that matters. If we manage to throw the British and Americans back into the sea, it will be a long time before they return.”

Bayerlein also admitted, “In France … [Rommel] believed that victory could no longer be gained by mobile warfare––not merely because of the British and American air superiority, but also because the German armaments industry was no longer capable of keeping pace with the western Allies in the production of tanks, guns, antitank guns, and vehicles.”

Battle for the Bunkers

At last, early on June 6, 1944, the mighty Allied invasion force was unleashed against the Normandy coast. After the American 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions dropped behind Utah Beach to sow death and confusion among the Germans, the 4th Infantry Division (Force “U”) stormed ashore; to the east, at Omaha Beach, the U.S. 1st and 29th Divisions (Force “O”) did the same.

While the 4th quickly overcame enemy opposition at Utah, Force “O” had a much tougher time, mainly because the air force and naval gunners initially had overshot their targets, leaving the bunkers untouched. Only when American destroyers came close to shore and fired point-blank at the casemates were the pinned-down amphibious troops able to make headway off the beach and up the bluffs.

At one of the German installations, a German soldier survived to write, “The heavy naval guns fired salvo after salvo into our positions. The hail of shells falling upon us grew heavier, sending fountains of sand and debris into the air. The fight for survival began. Our weapons were preset on the defensive fire zones, thus we could only wait. We had planned that [the enemy] should land at high tide … but this was low tide. Slowly the wall of explosions approached, meter by meter, cracking, screaming, whistling, and sizzling, destroying everything in its path. There was no escape.”

But, because aerial and naval bombardments had only a limited effect on the stout bunkers, once Allied boots were on the ground in Normandy the fight to knock out the bunkers really began. The installations guarding Utah and Omaha Beaches were engaged almost immediately; some garrisons gave up quickly while others held out for several days.

Grandcamp-Maisy

Grandcamp-Maisy is a small port to the west of Pointe-du-Hoc controlling the bay of the Grand Vey and the mouth of the Vire River with a commanding view of Utah Beach, 12 miles to the west. At this location the Germans had installed two coastal gun batteries equipped with guns that had enough range to hit Pointe-du-Hoc but not either Utah or Omaha Beaches.

Nevertheless, because they posed a danger to the Allied fleet, the batteries at Grandcamp-Maisy had to be destroyed. On the night of June 5-6, a fleet of 100 Allied bombers dropped nearly 600 tons of bombs on the batteries but failed to make much of a dent; on D-Day, the German guns opened fire on the American fleet supporting the landings on Utah Beach.

On June 8, the 3rd Battalion of the U.S. 116th Regimental Combat Team, supported by the 743rd Tank Battalion, entered Grandcamp-Maisy and, by the end of the day, had neutralized the battery.

St. Marcouf/Batterie Crisbeq

Despite their commanders’ orders to fight to the last man and the last bullet, most German coastal batteries were either neutralized or their crews gave up quickly after offering only token resistance on D-Day. The six-gun Batterie Crisbeq at St. Marcouf was an exception, managing to hold out for several days. Although bombarded by thousands of tons of bombs (600 tons on June 5 alone) that destroyed all the antiaircraft guns, the Kriegsmarine crew, commanded by Oberleutant zur See Walter Ohmsen, fought back with unusual tenacity.

Guarded by eight antiaircraft guns, 15 machine guns, and ringed by minefields and barbed wire, Crisbeq withstood an attack by the 1st Battalion of the 101st Airborne Division’s 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment on the night of June 6 (20 of the airborne troopers were captured during the abortive assault), and the next day its 210mm guns even managed to sink the destroyer USS Corry, three miles away. The American battleships Nevada, Arkansas, and Texas responded by knocking out two of the German bunkers.

On June 7, after a 20-minute bombardment by naval guns, artillery, and mortars, two companies of the 1st Battalion of the 4th Infantry Division’s 22nd Infantry Regiment assaulted the Crisbeq position. The Army’s official history says, “Advancing then under a rolling barrage which the infantry followed at about 200 yards, and under indirect fire from heavy machine guns, the two companies reached the edge of the fortified area with few losses.

“The third company was then passed through to blow the concrete emplacements with pole charges. The assault sections, however, used all their explosives without materially damaging the concrete and then became involved in small-arms fights with Germans in the communicating trenches.”

Oberleutant Ohmsen, who had relocated his command post to the nearby Azeville battery, then had the Azeville guns saturate the Crisbeq site with heavy caliber fire that forced the 22nd Infantry’s 1st Battalion to withdraw to its starting point north of Bas Village de Dodainville.

On June 8, more Allied warships again pounded Crisbeq with their big guns, but still the battery would not quit. On the night of June 11-12, the 78 surviving Germans, having slowed the American advance in their sector for nearly a week, abandoned the battery and withdrew. Ohmsen was awarded the Knight’s Cross for his defense of the Crisbeq battery.

Pointe Du Hoc

One of the best known episodes to come out of Operation Overlord is the Ranger assault on the six-casemate German battery at Pointe-du-Hoc, located between Utah Beach to the west and Omaha Beach to the east. Two hundred and fifty men of Lt. Col. James Rudder’s U.S. 2nd Ranger Battalion were tasked with climbing the 100-foot-tall cliffs on the seaward side and taking this position.

To protect the guns from the intense air bombardment, the Germans, prior to the attack, had moved many of them approximately one mile away on June 4; poor weather conditions just prior to the invasion prevented reconnaissance flights from discovering the removal of the guns.

While reviewing the plans for the invasion, a senior American naval officer remarked to General Omar Bradley, commanding the American forces on D-Day, “It can’t be done. Three old women with brooms could stop the Rangers scaling that cliff!”

Rudder was undeterred. “Sir, my Rangers can do the job for you,” he replied.

Nevertheless, the German garrison at Pointe-du-Hoc fought back stubbornly as the Rangers, under the supporting fires of the American destroyer USS Satterlee and the British destroyer HMS Talybont, climbed the sheer cliff using ropes and ladders borrowed from the London fire brigades.

After the Rangers reached the top and fought off several counterattacks, they were surprised to find no guns in the casemates. A patrol went off in search of the guns, found them in an orchard a mile away, and destroyed them with thermite grenades.

British Assault

East of the American beachheads, in the British/Canadian sectors, the bunkers closest to the beaches were attacked within a day or two of the landings, but those farther up the coast in the direction of Calais were taken out as the number of invaders steadily grew and pushed their way inland.

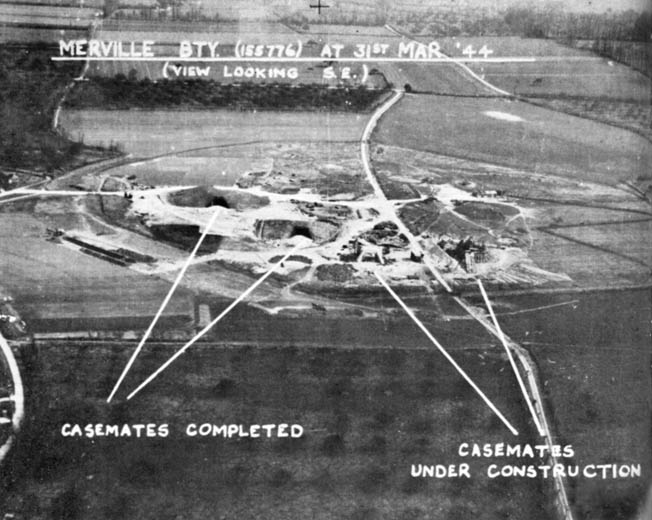

In the British sector, the coup-de-main glider assault under Major John Howard swiftly took the vital bridges over the Orne River and Caen Canal, but another airborne assault to knock out the four casemated guns at Merville on the far right flank of Sword Beach proved the adage that “anything that can go wrong will go wrong.”

Lieutenant Colonel Terence Otway’s 9th Parachute Battalion landed at Merville with only a fraction of its expected number; the rest landed miles off target. Most of the unit’s demolition equipment was also missing. Only through courage of the highest order were Otway’s men able to break through the barbed wire and minefields that surrounded the casemates to kill, capture, or scatter the defenders and disable the guns.

Longues-Sur-Mer

Located five miles north of Bayeux, between Omaha and Gold Beaches, the Kriegsmarine Longues-sur-Mer battery, also known as Wiederstandnest 48, was sited atop a 220-foot-high cliff. Construction began on September 1943 but was not completely finished by the time of the D-Day landings. Although manned initially by the Kriegsmarine, the battery was later transferred to the army.

The battery was composed of four large concrete casemates, a fire-control post, shelters for personnel and ammunition, and several defensive machine-gun emplacements. Each casemate was outfitted with a 152mm (six-inch) German naval gun with a range of up to 12.5 miles, enough to reach the Omaha and Gold Beach sectors.

During the night of June 5, Bomber Command tried to hit the battery with 1,500 tons of bombs, but most fell on the nearby village. Some of the bombs did destroy the telephone lines between the observation bunker and gun positions.

A backup system of signal flags was used, but the smoke from the guns made the flags impossible to see; the German gunners had to engage targets with open sights (no optical rangefinders had been installed), and at dawn the guns fired on the closest large ship—HMS Bulolo, the headquarters ship for the staff directing the Gold Beach landings—forcing Bulolo to retreat out of range.

The American battleship Arkansas and the Free French cruisers Montcalm and Georges Leygues arrived and began bombarding the position. During the duel, three of the battery’s four guns were disabled by British cruisers Ajax and Argonaut, which had joined in later; the lone remaining gun continued to fire intermittently until 7 pm, when the Georges Leygues silenced it. It is estimated that the battery had fired over 150 rounds at the fleet but did no damage.

On the morning of June 7, the major commanding the Longues-sur-Mer battery and his 184 men surrendered to elements of the British 50th (Northumbrian) Division.

Mont Canisy

The Mont Canisy battery at Bénerville was one of the most important German positions between Le Havre and Cherbourg. Located on the highest ground in Normandy (360 feet), the French Navy constructed in 1935 a battery atop Mont Canisy with its unrestricted view of Le Havre to the north and which was operational there until 1940.

Following the fall of France in 1940, the French abandoned the position and the occupying German forces took it over; they, too, recognized the obvious importance of the location and improved the site, constructing a battery of four 155mm guns that could threaten any attempt to take the port by sea.

Mont Canisy was an army battery and was known to the Allies as Batterie Bénerville. Initially, the guns were in open emplacements with a 360-degree traverse, but to protect the guns from aerial attack Organization Todt encased them in Type 679 casemates. The site was also protected by a Renault tank turret. A 275-yard-long tunnel, 50 feet below ground, connected the casemates and the ammunition bunker.

At 5:30 am on D-Day, the British battleships HMS Ramillies and HMS Warspite became the first Allied ships to open fire on the Norman coast at a range of some 25,000 yards (14 miles) offshore.

While the battery was under fire, the German 5th Torpedo Boat Flotilla attacked the two British battleships, firing 18 torpedoes at the dreadnaughts. As the torpedoes headed toward Ramillies, the ship turned, and the “fish” passed between her and Warspite, hitting the Norwegian destroyer HNoMS Svenner, which immediately sank with a loss of 33 crewmen. Seeing the huge Allied naval force, the German E-boats headed back to their base at Le Havre.

Despite being saturated by hundreds of bombs and shells, the Mont Canisy gunners continued to fire, managing to sink one ship and hit 34 more, badly damaging 12 of them.

A plan was formulated to launch a commando attack on the battery, but as the guns could not fire inland it became a meaningless target; the Allied commander decided to simply bypass Mont Canisy and let it wither on the vine. The Germans abandoned the battery during the night of August 21-22 without a fight and were taken prisoner.

Buologne

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery told Lt. Gen. Henry D.G. Crerar, commanding the First Canadian Army, “I want Boulogne badly.” Crerar did his best to comply with his superior’s desires.

The port of Boulogne was an essential prize, but it could not be taken unless and until the big guns at Cap Gris-Nez and Calais were silenced. So a plan, Operation Undergo, was formulated to do the job.

The defenses were formidable. Atop Cap Gris-Nez itself, between Boulogne and Calais, was Batterie Gris-Nez with its 10 casemated batteries, each with 175 men (as well as V-1 and V-2 launching sites). A mile to the south at Waringzelles were the four great casemates of Batterie Todt; at nearby Floringzelles stood the four 280mm (11-inch) guns of Grosser Kurfürst. Three miles east of the cape was a battery at Wissant, while the awesome Batterie Lindemann sat imperiously atop the Noires Mottes escarpment near Sangatte. There were other batteries at Fort Lapin and a two-casemate battery known as Oldenburg housing 240mm (10-inch) guns northeast of Calais.

On September 10, the Canadian 2nd Division surrounded Calais and began a siege. Then the Canadian 3rd Division’s 7th Infantry Brigade, along with the Toronto Scottish Regiment and a regiment of the 17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars, mounted a ground assault against the Cap Gris-Nez batteries, manned by the 242nd Naval Coastal Artillery Battalion. They were initially repelled.

On September 17, while the Canadian 2nd Division continued its attack, the Canadian 3rd Division, supported by the 10th Armoured Regiment, detachments from the 79th Armoured Division, and the 328 guns of 17 artillery regiments, began their assault on Boulogne.

As part of the assault, the three infantry battalions (Royal Winnipeg Rifles, Regina Rifles, and 1st Canadian Scottish) of the 7th Infantry Brigade, along with the North Shore Regiment (New Brunswick), were assigned to silence Lindemann’s four 406mm guns that were, along with the Todt and Grosser Kurfürst batteries, continuing to shell Dover. To support the attack, Crerar also threw in tanks and artillery, including the long-range heavy guns firing from Dover.

The assault on Boulogne (Operation Wellhit) began with the Canadians sealing off escape routes from the city before attacking with tanks, artillery, aircraft, and infantry. On September 20, a force of 600 bombers dropped 3,000 tons of high explosives on German positions. Six days later, the 10,000-man German garrison, after putting up a half-hearted fight, surrendered.

Wellhit ended with the capture of Wimereux, Wimelle, and the fort of La Crèche. The last two nearby German defensive positions, in Le Portel and Outreau, fell once the Boulogne fortress commander, Lt. Gen. Ferdinand Heim, who had vowed to fight to the death, changed his mind and surrendered on September 22.

Calais

The main attack on Calais commenced with the Canadian 3rd Division’s 7th Brigade, bolstered by the North Shore Regiment, the Queen’s Own Rifles, Cameron Highlanders, and another Canadian unit, Le Régiment de la Chaudière, all going into action on September 25. The Germans defended stubbornly, but theirs was a lost cause.

On that same day, the Grosser Kurfürst battery at Floringzelle was essentially knocked out by the long-range Dover guns, and Canada’s Highland Light Infantry easily mopped up on September 29.

Also on the 29th, the North Nova Scotia Highlanders captured Battery Todt. The infantrymen were supported by artillery and by tanks from the 6th Armoured Regiment and 79th British Armoured Division. One historian noted that as firing died down Lt. Col. D.F. Forbes, commanding the North Nova Scotias, “knocked on the steel door of one of the casemates and inquired about the strength of the garrison.” The Germans soon came out with their hands up.

On the 30th, following an intense artillery and fighter bomber saturation, a succession of strongpoints in and around Calais were taken; by October 1, the city was in Canadian hands. The 7,500-man garrison surrendered at a cost of only 300 Canadian casualties.

Perhaps the most dramatic ending at any battery came at Battery Friedrich August at La Trésorerie on September 18 when, while under heavy assault by the North Shore Regiment and accompanying tanks, the commander and his second-in-command of the three 305mm casemated guns, seeing their position as hopeless, loaded demolition charges into one of their guns, strapped themselves into the firing seats, and blew the gun and themselves up. Their 450 men surrendered.

At last, the Normandy coastal batteries were neutralized, and the Allied forces that had knocked them out were employed elsewhere in the drive eastward to liberate the other occupied countries of Europe and thrust into the heart of Nazi Germany.

The Atlantic Wall Today

Exploring the remains of the Atlantic Wall bunkers today is a fascinating, rewarding experience, and the fact that many bunkers are not marked on maps and remain forgotten under foliage makes it even more of a challenge. But “bunker hunters” are advised not to violate “no trespassing” signs or attempt to crawl into some of these spaces, as hidden dangers lurk within.

The Longues-sur-Mer battery site is one of the most visited and best preserved in France—and the only one where visitors can still see the original guns that were capable of firing shells weighing 100 pounds a distance of more than 13 miles. The view from the firing command post, dug into the cliff, offers a vast panorama over the Bay of the Seine. It is the only coastal defense battery on the landing beaches that is classified as a “historical monument.”

After the war, Battery Todt’s huge naval guns were dismantled and shipped to Norway for use in a gun battery run by the Norwegian Navy on an island in the Oslo fjord. The guns were later returned to France but their fate is unknown.

One of Todt’s surviving three casemates (“Turm I”) was privately purchased some years ago and turned into the Atlantik Wall Musée, which displays World War II weapons, uniforms, vehicles, ammunition, and one of only two Krupp M-5 280mm railway guns still in existence.

Mont Canisy, just a few miles south of Le Havre at Bénerville, is today incorporated into a nature preserve at the top of the hill; signs point the way. A postwar effort to destroy the casemates failed, and today volunteers on summer weekends conduct guided tours through 300 yards of underground tunnels. Incongruously, the site is surrounded by luxurious, multi-million-euro mansions.

Some batteries no longer exist. Battery Lindemann, once the largest in France, was totally demolished to make room for the approaches to the Chunnel—the underwater tunnel that links France with Britain.

Unmarked bunkers, however, abound. For example, a complex being slowly absorbed by foliage is found along the D-513 roadway west of Honfleur, still overlooking the Seine Estuary south of Le Havre.

High on a bluff just north of La Havre, the graffiti-marred, open-top gun platforms of St. Adresse still offer a commanding view of the sea. Other bunkers are still in place around Boulogne and still look menacing.

Interestingly, long lost bunkers continue to be uncovered. A decade ago, Gary Sterne, an amateur historian from Britain, found an annotated military map in a pair of GI trousers he bought. On the map was a spot near the village of Grandcamp-Maisy marked “area of high resistance.” Sterne decided to visit Normandy and examine the site.

“It sparked my curiosity because that area was previously thought to be just fields,” he said. “To my amazement, I found I was standing on concrete. I followed the concrete to the edge of the tree line and discovered a bunker entrance, then a tunnel, an office, storerooms, headquarters buildings, radio rooms, bunkers.”

The battery, he believes, was manned by about 180 soldiers of the 716th Artillery. He began digging and found discarded German water bottles, spectacles, and boots. The remains of one officer, too, were uncovered; the remains were reburied at the German military cemetery at La Cambe.

The “Maisy battery,” as he determined it was, was built on the far side of the slope behind Omaha Beach. Company F of the 5th Ranger Battalion stormed the site and captured it after five days of furious hand-to-hand fighting (June 6-10), taking 86 prisoners at a cost of 15 Rangers. American veterans have told Sterne that they discovered more than $4 million worth of French francs, which they shared among themselves.

“After studying the RAF reconnaissance photographs, it was clear that the site was of major importance,” said Sterne. “It was not just another little gun battery, but a major complex—a similar size to that at Pointe-du-Hoc, but virtually undamaged.”

After doing excavation work, Sterne bought the 40 acres of land from more than 30 different owners, and he plans a museum. Most of the site is now open to tourists, and there are miles of trenches to explore, as well as some of the battery’s original artillery pieces. Today, it and Longues-sur-Mer are the only Atlantic Wall batteries with their original guns.

Even today, with most of the Atlantic Wall bunkers in derelict condition, they still possess a somber, sinister grandeur, and it is easy to appreciate the tremendous amount of effort that went into building them. It is also sobering to realize that, no matter how impressive Hitler’s Atlantic Wall—on which many years and many billions of Reichsmarks were expended—was, it was penetrated by the Allies in the span of a few hours.

Some parts of the wall have been demolished, some have crumbled or fallen into the sea. Wall worker Rene-Georges Lubat said, “I do think the wall should be preserved now. It is important to remember what happened—the ignominy of it all, the cataclysm that we had to endure.”

Will France ever declare the Atlantic Wall—or at least of portions of it—a historic monument, thus ensuring its preservation? “That will never happen,” said a BBC reporter. “No French government would elevate a symbol of national dishonor.”

Hitler’s Third Reich did not last for a thousand years. But the remnants of his Atlantic Wall just might.

The Germans did use fixed Flame Throwers as defensive weapons in Normandy. These weapons were quite small probably 14” high, buried with only a nozzle sicking above the ground and controlled by a buried wire from the firing position. They proved to be of limited use as they were easily damaged, had limited range and could only be used once, and only covered as small area.

The British artillery close to Dover which dueled with German artillery near Calais was not in bunkers.

Several years ago I received an email describing how a winter storm in Denmark had uncovered a previously unknown abandoned German bunker. Attached photos showed bunks with blankets still on them, tables with plates utensils and cups, and abandoned equipment.