by David Alan Johnson

The deliberate crashing into enemy targets by Japanese aviators did not begin at the Battle of Santa Cruz Islands. The first suicide attack against American shipping took place at Pearl Harbor, over eight months earlier, when a bomber crashed into the seaplane tender Curtiss and set her on fire. Attacks of this kind, including the crashes into Hornet and the destroyer Smith, were known as kesshi, “dare to die tactics.”

[text_ad]

Skip-bombing and ramming were also adopted. Skip-bombing involved fitting a Zero fighter with a 550-pound bomb, which was to be released 200 to 300 yards from an enemy ship. These were not exactly suicide tactics, although they were extremely hazardous. The bomb might bounce up and hit the Zero, or the explosion of the bomb could destroy the plane. A training program for skip-bombing was carried out in the Bohol Strait, near Cebu, but all training was stopped in September 1944, when American aircraft destroyed 50 percent of the air group.

Most Suicide Attacks Were Spontaneous Actions

Deliberately crashing into an enemy target was not limited to shipping; it was used successfully against enemy planes as well. A Japanese flight sergeant rammed his fighter into a B-17 Flying Fortress bomber on May 8, 1943. He was protecting a convoy off the coast of New Guinea and made the decision to kill himself and take the American bomber and its crew with him. Over a year later, the pilot of a two-man Nakajima Gekko night fighter (codenamed “Irving” by the Allies) used the same tactics to bring down a B-24 Liberator bomber.

Most of these suicide attacks were spontaneous actions—a pilot making a heat-of-battle decision to end his own life by destroying an enemy ship or airplane. But as Japan’s chances of winning the war became less and less likely, the strategy of suicide grew in direct proportion. Informal discussions of organized suicide attack began in 1943. In March of that year, the chief of the Army Aeronautical Department, Takeo Yasuda, secretly established a Special Attack Corps training program—a forerunner of the kamikaze corps.

” We Must be Superhuman in Order to Win the War.”

The commander of the First Air Fleet, Kimpei Teraoka, made these telling observations: “Ordinary tactics are ineffective. We must be superhuman in order to win the war.” On the subject of suicide units, he commented, “If all air units do it, surface units will also be inclined to take part.”

Teraoka was right—the idea of the suicide attack unit spread. Admiral Soemu Toyoda, commander in chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy, was won over by what has been called the “vanity of heroism” and officially consented to the creation of the Special Attack Corps, or the kamikaze. The Special Attack Corp’s slogan was “One plane, one warship.”

Pilots did not have to be highly trained to undertake suicide missions. In fact, suicide pilots usually received only the minimum of flight training. Kamikaze pilots sank or damaged hundreds of ships during the latter part of the war.

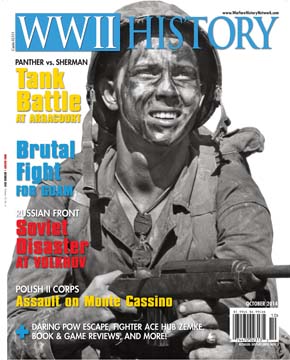

This article is from the May 2009 issue of WWII History Magazine. If you would like to read the rest of this and other articles, visit our order page to see which digital editions we have on offer.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments