By Samantha L. Quigley

They said it couldn’t be done. Doubters chided Henry Ford for declaring that his Willow Run Bomber Plant could turn out a B-24 Liberator heavy bomber every hour. They’d called him crazy in 1896, too, but Ford ignored the naysayers, pushing past obstacles and failures until his gasoline-powered horseless carriage rolled down the streets of Detroit. His creation, which he christened a “Quadricycle,” featured an engine with the equivalent pulling power of four horses. It was the machine that would transform a world and help win a war.

With the “War to End All Wars” in America’s rearview mirror, the country was focused on the positive. Having lost any appetite it had for war, most of America was confident there would never be a future need for war machines. Or the military.

After World War I, Congress decreased the military’s overall numbers. It also passed laws denying tax breaks to companies that owned equipment that could make weapons of war.

“Bethlehem Steel, the largest arms producer in the world, destroyed all their arms-making capability in 90 days to avoid the taxes,” Randy Hotton, a pilot and former direc- tor of the Yankee Air Museum in Ypsilanti, Michigan, said during a presentation in June 2015. “DuPont Corporation, which had been contracted to build seven [gun] powder factories for World War I, had spent $25 million of its own money. The government, when the war was over, cancelled the contract and basically said, ‘Because there’s no more war, we don’t need your powder.’” Meanwhile, the powers on the losing side of World War I were rearming and, without admitting it out loud, the United States was worried it might get dragged into another war. Just in case that happened, in November 1929, then Major Dwight D. Eisenhower was called upon to create a plan to make sure the country could mobilize its military if it needed to. There was just one problem. The Great Depression was in full swing and Congress wouldn’t fund the plan.

Four years later, the situation in Europe started heating up. Adolf Hitler rose to power and brought Nazi law to Germany. By 1938, Germany had annexed Austria and the Sudetenland—the German-speak- ing part of Czechoslovakia along the German border.

Through all of this, the United States maintained its isolationist ideals. November 9, 1938, changed that thinking. On what is referred to as Kristallnacht— the Night of Broken Glass—the Nazis terrorized German Jews, breaking windows of homes, businesses, and burning synagogues.

Soon after, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Congress for 10,000 airplanes. Seven months later, while still claiming America wasn’t interested in getting involved in Europe’s war, Congress granted a compromise—5,500 planes over five years, according to Hotton.

By May 1940, Germany had invaded Poland, Belgium, France, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. “This is the blitzkrieg,” Hotton said. “This is the mechanized infantry with airpower. Air power is now decisive. If you do not control the air over the battlefield, you will not win the battle.”

With the 12th largest Army in the world—behind Brazil—America’s military was not the powerhouse it is today. “We had 32 tanks in the U.S. inventory,” Hotton said, comparing that figure to the nearly 6,000 tanks—German and Allied— that were involved in the May 1940 Battle of France. “We had the 18th largest air force in the world—326 ‘modern’ airplanes that were obsolete by world stan- dards. We had 54 heavy bombers.”

It was becoming much clearer that the U.S. needed to ramp up production, and fast. While foreign demand for war equipment—especially airplanes—skyrocketed and helped prop up America’s fragile Depression-ravaged economy, Roosevelt remembered the problems encountered in World War I, when it had taken America too long to mobilize its forces. He went back to Congress and asked for a whopping 50,000 planes a year.

“When Hermann Göring, head of the German Luftwaffe heard this, he laughed,” Hotton said. “He said, ‘No one can build 50,000 planes a year. That’s pure propaganda.’” The U.S. would have the last laugh. In 1944, the U.S. would build nearly 100,000 airplanes.

Roosevelt didn’t have faith in the government to get America to a place where it could mobilize effectively, so he turned to the automotive industry with its efficiencies and understanding of mechanization. Bill Knudson, the then-president of General Motors, was a Danish immigrant who had worked his way up the auto industry ladder. “He knew everybody and he knew how factories worked,” according to Hotton.

But Knudson faced multiple problems, including the fact that nobody knew what they wanted. The Army was still ordering horse saddles for the cavalry at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

But the auto executive also knew the mechanisms to mobilize America—the tools to make weapons of war had been destroyed. He knew, too, it would take 18 months to get them in place and another 18 months to produce at peak levels.

“He said, ‘Aircraft and aircraft engines are the biggest problem we’re going to face, and only the auto companies have the capability of building these airplanes and engines,’” Hotton noted.

While that was true, it wasn’t that simple. Knudson faced a political hurdle—the Army and the airplane companies didn’t want the automakers involved in building airplanes. But the Battle of Britain—Germany’s sustained bombing raids on the island and Britain’s efforts to oppose them—opened eyes to the serious threat of the German air force.

“Bombers are now the offensive weapon,” Hotton said. “The U.S. identifies the four-engine bomber as what we need to fight the war. The distances in the Pacific to fight the Japanese are long. We need the long range of the bombers. We need airplanes that can carry tremendous loads tremendous distances.”

After the Battle of Britain ended in the autumn of 1940, the United Kingdom asked for more bombers. Roosevelt turned to Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall and asked him to fulfill the request. Marshall’s answer was a serious wake-up call: He only had 32 bombers left in the U.S. and if he gave them up, he wouldn’t be able to train his crews.

Bomber production suddenly became a top priority. In October 1940, Knudson, who had resigned his position with GM to become the government’s chairman of the Office of Production Management earlier that year— rounded up the heads of Studebaker, Nash Motors, GM, and Hudson Motor Car Company in New York and boiled down the dire situation: America needed bombers—more than it could hope for and sooner than it dared to ask for them.

The auto industry leaders were in Detroit two weeks later, matching items they were already making for cars with similar items needed to make airplanes. The automakers said they could make all the pieces required to build the much-needed bombers.

Factories to assemble the planes were also under construction. Tulsa, Oklahoma, would build B-24s; Kansas City, Kansas, B-25s; and Omaha, Nebraska, got the B-26. But in December 1940 the focus shifted to the B-24s.

“The B-24 is the most problematic airplane that the Army has on its list,” Hotton said. “It’s faster, carries more, goes further than the B-17, and they want the B-24.” Consolidated Aircraft had a contract to build the planes, but it had only completed seven and delivered just three. The Army decided the way to build the B-24 was through a collective effort and World War I pilot, aviation pioneer, and racer Jimmy Doolittle would facilitate that effort.

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked American military facilities in Hawaii and the Pacific, and the U.S. was now in the new world war. Although too old to volunteer for World War II, Doolittle was called by Congress back to active duty for his expertise. Doolittle, who would gain fame for his air raid on Tokyo on April 18, 1942, held the first Ph.D. in aeronautical engineering issued in the United States.

The military assigned him to Detroit to enable a “shotgun marriage between the auto companies and the aircraft companies,” Hotton said. To make that happen, Dolittle turned to Henry Ford and his precision assembly line to build parts. Ford agreed, until Charlie Sorenson—his right hand at Ford Motor Company—visited Consolidated’s San Diego operation in January 1941. He was floored by the haphazard way the planes were being assembled.

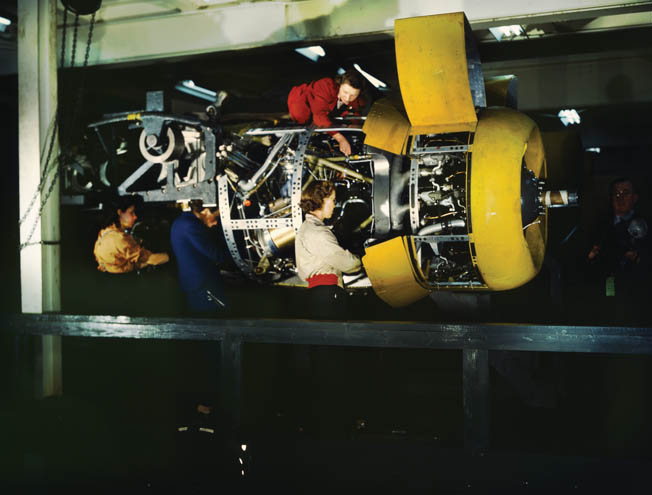

“They were building aluminum airplanes outdoors on steel fixtures,” Hotton said. “They’ve got a surveyor’s transit on pallets in the back of a pickup truck with a guy looking at the center line of the prop shaft to line it up. [It took] four hours to hang an engine.”

Reuben Fleet was the head of Consolidated and the company was proud of its product. So, Fleet, offended when Sorenson expressed his dismay, asked him how he would do it better. “Sorenson loved a challenge and he said, ‘You know what? I don’t know, but I’ll have an answer for you in the morning,’” Hotton said. With 35 years of manufacturing experience, Sorenson broke the B- 24 down into assemblies, subassemblies, and parts for subassemblies—all diagramed in pencil on hotel stationary.

The next morning, he showed Fleet his plan––and was told it couldn’t be done. Fleet asked if Ford would build parts for Consolidated and was met with Sorenson’s definitive answer: Ford wasn’t interested in building subassemblies. It would build complete airplanes or nothing.

“[The Army Air Force] been looking for somebody who could answer their bomber production problem and Ford stepped up and gave them the answer they wanted to hear,” Hotton said. Based on pencil sketches, the Army, desperate for B-24s, awarded Ford a multi-million dollar contract to build the bomber plant and the airplanes. The contracts were signed in February and the logistical debates started almost immediately.

By April 1941, the construction had already begun on four flat acres of Michigan farmland outside the village of Ypsilanti, 25 miles west of Detroit. In May, the project was scaled up based on government assurances Ford would be building complete B-24s.

Initially, it had been thought that the Willow Run plant would handle the final assembly of the B-24s from the parts manufactured at Ford’s Rouge Complex in Dearborn, 28 miles away. Marshall kyboshed that idea, pointing out the potential for damage to the parts in transit.

The decision that Willow Run would build complete bombers—parts to plane— called for a bigger plant. Had it just been tacked on to the end of the existing building, it would have landed in the middle of the planned airport.

Explained Hotton, “So the guy in charge of the factory design said, ‘We’ve got to make a 90-degree turn. And since we’re making a 90-degree turn, we might as well keep the factory inside Washtenaw County [Ypsilanti],’” noting that keeping the factory in one county would also provide a postwar tax benefit.

By November 1941, all the airplane factories had been built—with Willow Run’s final square footage of 4,734,617 million—and the airplanes we would fight WWII with were in production, according to Hotton.

“FDR had given the U.S. an 18-month head start on WWII,” he said. “Time magazine said this in February of 42: ‘The miracle of American productivity was something Hitler didn’t understand.’ He fully understood it. He was deathly afraid of it. But, based on German experience, he thought it would take the U.S. four years to mobilize, and he would have won by that time.”

If Hitler had walked through Willow Run in 1942, his assessment might have appeared accurate. Ford was building the B-24s at Willow Run, but Consolidated was still in charge and it had no blueprints for Ford to work from—just sketches, drawings and tem- plates. The materials were nothing Ford could use in his efficient assembly line, so he had 200 engineers work in shifts around the clock, seven days a week. They produced five miles of drawings a day based on Consolidated’s materials. Ten thousand of the 30,000 drawings the engineers made were obsolete by the time they got them back to Detroit from San Diego.

“All the tooling they designed now doesn’t work because [Consolidated] changed the airplane every day,” Hotton said. “This gives Ford a six-month delay in their production schedule because they thought they’d have all this equipment.”

The media was watching all of this closely and the Detroit Free Press ran a story boasting that Willow Run would be able to build a bomber a minute by summer. “And, of course, it was written in the paper, so it must be true,” Hotton said jokingly.

Not only was a bomber a minute a pie-in-the-sky dream, but Willow Run was supposed to deliver its first model in May 1942. It didn’t fly until September. The media started referring to Willow Run as “Will It Run?”

The delays, as the Truman Committee discovered, were not Ford’s fault. Headed by then-Senator Harry S. Truman, the group was charged with rooting out graft and corruption in the defense industry. “He’s sent to look at Willow Run,” Hotton said. “The government is looking at nationalizing Ford Motor Company to take over Willow Run.”

What Truman found was that the delays were a result of Consolidated being allowed to call Willow Run and make changes whenever they wanted. And they did. Every day. Truman’s Committee gave Willow Run a clean bill of health, noting all the “meddling from Consolidated was keeping things from moving forward,” Hotton said. It called for a single plant manager with the authority to make decisions affecting the day-to-day operations of the plant. From that point on, the plant manager made the calls and production picked up.

Meanwhile, able-bodied men were drafted or volunteered for military service and Ford started hiring women. By May 1942, 15 percent of the Willow Run workforce was women and they were earning the same wages as men did for the same jobs. Thirteen months later, employment peaked at 42,000, and by summer 1944, the factory was humming along. Production had peaked at a bomber an hour, just as Henry Ford had promised, and employment was reduced to 17,000, thanks to the efficiencies the auto industry had applied to making the B-24.

The center wing assembly was key to meeting that bomber-an-hour quota, Hotton said. “All the prefabricated structures had all been premanufactured. They didn’t have to be fit. They would snap into place.”

Workers put the parts in the wing. Riveters knocked the wing parts together. Then the center wing assembly was sent to a multiple-function machine that completed 42 precision machining operations to .0002-inch in 17 minutes.

“Six-and-a-half man-hours were invested in those center wings,” Hotton said. “Consolidated had about 1,500 hours involved in their center wing.” From there, all of the remaining pieces—all pre-made and waiting—were fit to the piece as it moved down the assembly line. Plumbing, wiring, landing gear, cockpit shields, instrumentation—all were added quickly and efficiently. The wings, however, could have been problematic.

“Henry Ford hired eight [dwarfs],” Hotton said. “And if you read the stories … they were very proud of what they were doing. For the first time in their lives, they weren’t … sideshows. They had a real job. They’d [climb] inside the wing and they’d hold the backing plates that hold the outer wing onto the center wing.”

Despite how smoothly the plant ran, putting out a bomber an hour still wasn’t an easy feat. Willow Run ran two nine hour shifts. The remaining four hours were used to restock parts and change tooling. That was the schedule six days a week.

By the end of the war, Ford had pushed 8,865 B-24 heavy bombers out the Willow Run doors for the Army Air Force. The plant went from building just one plane a month in October 1942 to nearly 500 a month by June 1944, with the capability of creating 650 B-24s a month by fall. The Army, however, slowed production to 200 bombers a month.

“The Army literally said, ‘Slow down. We have no place to park them. The losses in combat haven’t been what we expected,’” Hotton said. By the time the last B-24 rolled off the Willow Run assembly line on June 28, 1945, the plant had produced more than 92 million pounds of airplanes. In 1944 alone, Willow Run produced nearly as many aircraft as the entire nation of Japan, according to The Ann Arbor Observer.

“Given the limited capacity of the aircraft industry, and the enormous pressure for airplanes, it was fair to conclude the Army Air Force was justified in underwriting this Ford experiment,” Hotton said.

A General Motors holding when GM declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2009, Willow Run was destined for demolition until a small Michigan organization known as the Yankee Air Museum stepped up. Backed by the Michigan Aerospace Foundation, the museum has been working for over four years to save a portion of the bomber plant. Once a sprawling military defense colossus, just 144,000 square feet were spared the wrecking ball.

Once restored, it will house the Yankee Air Museum, which will be renamed the National Museum of Aviation and Technology at Historic Willow Run.

“At a dark time in American history,” Hotton said, “the U.S. turned to Detroit to save the world—literally. While we might not think of Willow Run as a large battleground … 100 years from now, people will come here to hear this story, and that’s what we have to preserve at Willow Run.”

Very interesting story. I am 97 years old and was a crew member on a B-24. Flew 25 missions with the 450th B.G 15th A.F. in Italy. I will always have a spot in my heart for the B-24 and those involved in it’s

production. I volunteer at the Lone Star Flight Museum in Houston and try to keep the memories alive.