by Thomas Haymes

The German mountain troops were dug into their shallow, frozen foxholes waiting for the enemy ski troops to appear across the horizon. Armed with a bewildering array of equipment salvaged from enemy depots and sunken ships, the Germans prepared to hold off yet another assault across the frozen landscape.

In an eerie foreshadowing of the upcoming campaign on the Eastern Front, the outnumbered and under-supplied German force was defending a shrinking perimeter as their only lifeline, the Luftwaffe, desperately attempted to keep the forces supplied. This landscape, however, was not in Russia, and the attacking ski troops were not Siberians but rather Norwegians and Frenchmen trying to drive German forces from their tenuous foothold in northern Norway.

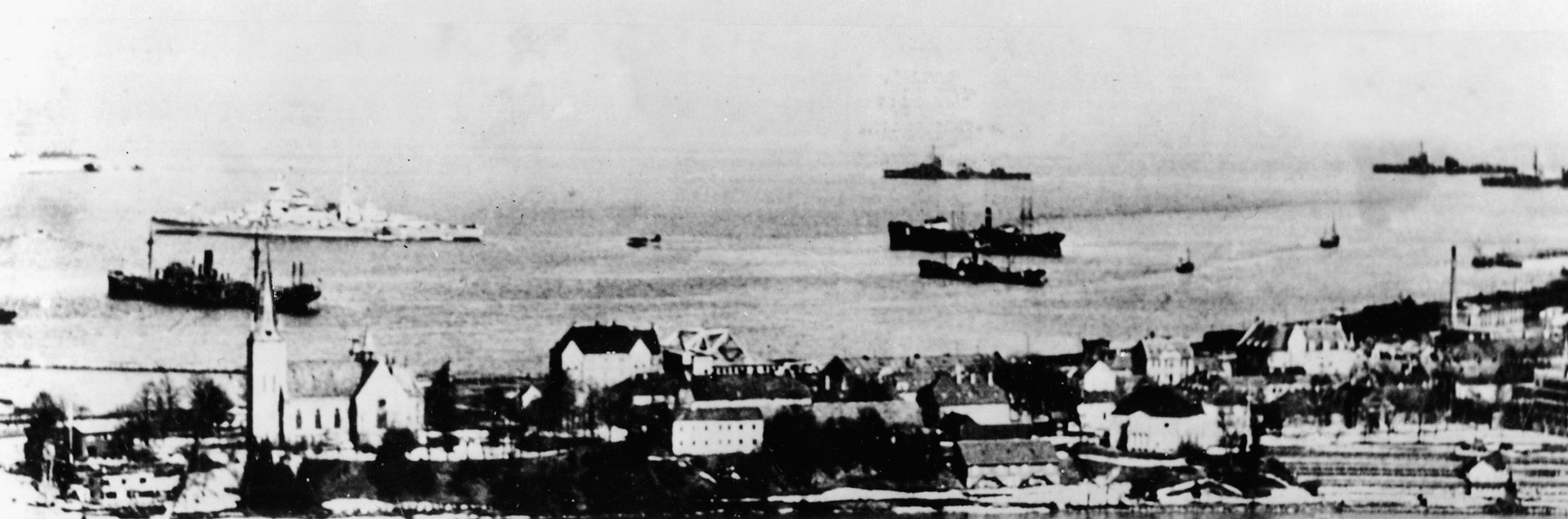

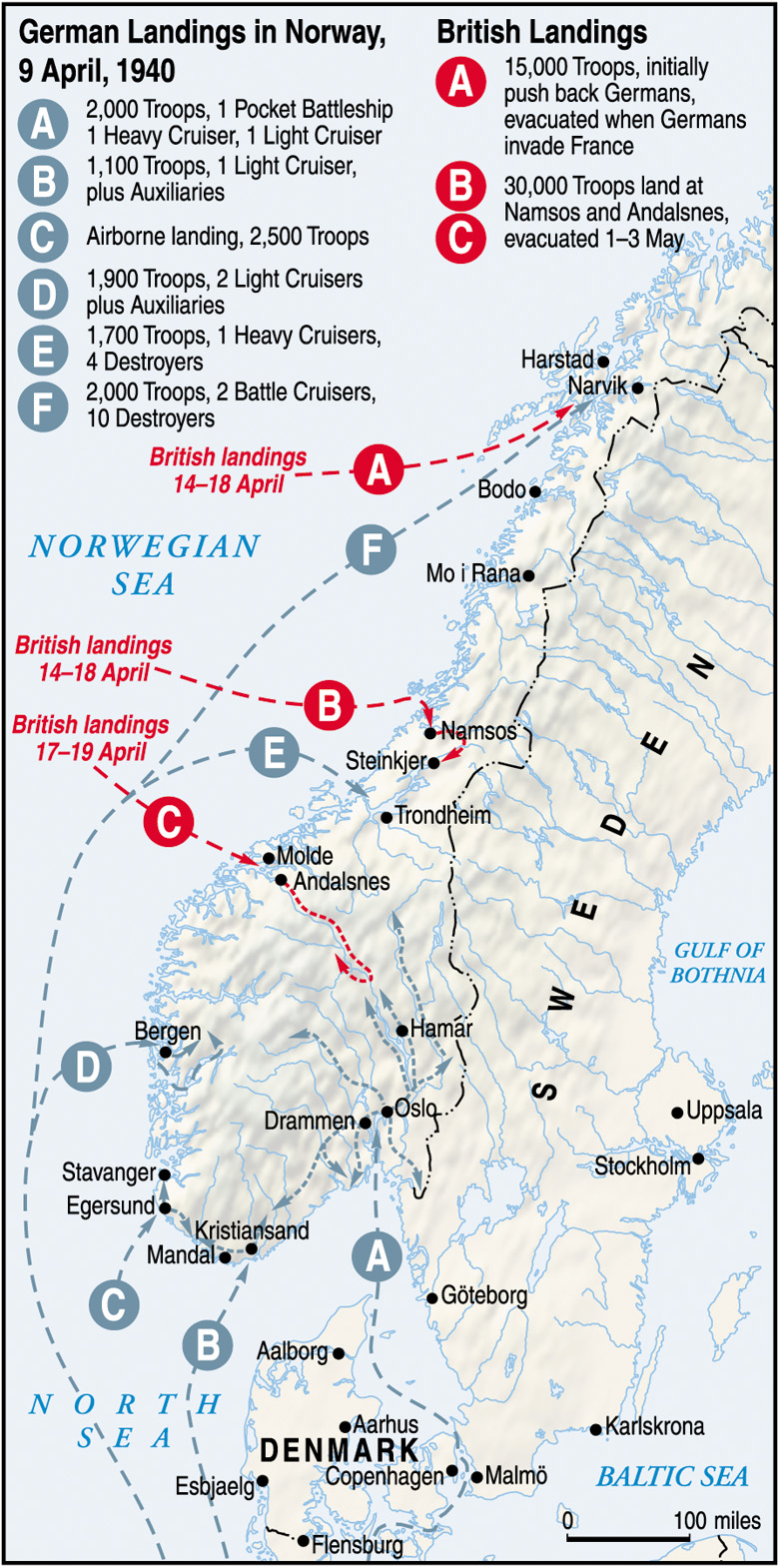

In April 1940, both Germany and Great Britain were looking at the strategic importance of neutral Norway. Aside from its strategic location flanking the sea lanes of the North Sea, it was also an important transshipment point for iron ore from Sweden to Germany. The unique geography of this part of Scandinavia is primarily east-west, whereas the countries of Norway and Sweden are primarily north-south. Thus, the iron ore mined in northern Sweden was more easily shipped from the Norwegian port of Narvik immediately to the west rather than traveling the length of Sweden to Germany. Both Britain and Germany realized how important this ore was to the German war effort, and early in 1940 both sides started to pressure Norway’s strict neutrality. Britain sought to interrupt the flow of iron ore by mining the sea lanes, but both sides realized that, strategically speaking, invasion offered the best prospect for achieving their aims. By April, both the Germans and the British were hastily preparing forces to land in Norway. Despite British preponderance at sea, Germany got there first, and starting on April 9, its forces descended along the length of the country.

Narvik, as the port that was the primary outlet for the Swedish ore, was a key part of this operation, but Narvik also held a lot of operational challenges as far as the Germans were concerned. Its location in the far north placed it outside of effective air support range, and the difficulty of the Norwegian terrain—not to mention the sheer distance involved—necessitated a naval operation to land troops from the sea.

Germany Sends a Flotilla to Narvik

Due to these factors, early on the morning of April 6, elements of the German 3rd Mountain Division were loaded onto 10 destroyers and slipped out of Bremen harbor for the 1,200-mile sea voyage to Narvik. With between 200 and 250 men crammed into each ship, there was not much room for equipment—particularly heavy equipment. The destroyers were an improvisation in any case because Germany had no real amphibious capability. Landings would either have to be accomplished via small boat or by backing up to a pier. In the event of resistance, this operation could quickly turn into a massacre, but the Germans were willing to take the risk because of the importance of Narvik to their war effort.

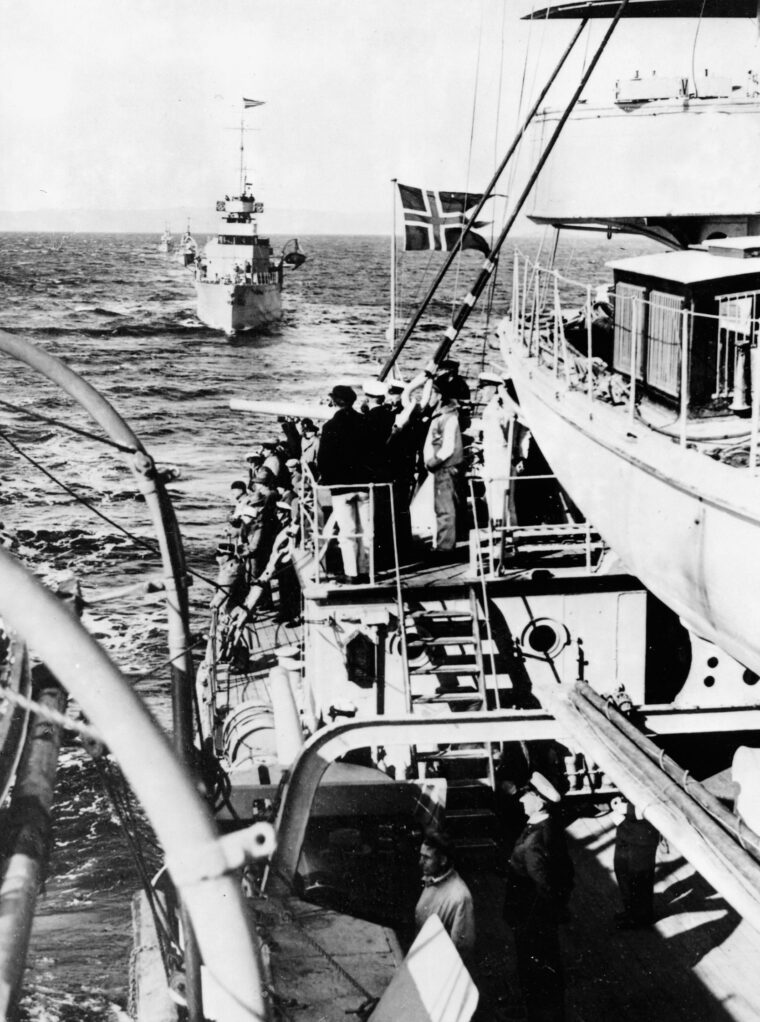

First, however, this group of destroyers had to make its way across a North Sea largely controlled by the British Home Fleet, which outnumbered German naval forces in just about every category. To provide some measure of cover for the force, the German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gniesenau, as well as the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper, were assigned escort duty for part of the journey. Until the capture of Norwegian airfields, there was no way to provide the force with air cover once it passed outside the range of German land-based fighters and bombers. Germany had no aircraft carrier force.

Rough weather washed 10 men and significant quantities of equipment and supplies overboard during the three-day voyage. There were also running naval battles with elements of the British fleet, resulting in the sinking of the British destroyer Glowworm on April 8 and the premature dispatch of the covering force to intercept heavier Royal Navy forces trying to head off the small fleet.

An Unknown Welcome Awaits the Germans

By the time the destroyers reached the entrance to Ofotenfjord, which led to Narvik harbor, they were essentially on their own. Intelligence about the defenses in the area was poor, and the German commanders feared that there might be Norwegian shore batteries guarding the narrow entrance to the fjord. Despite the efforts of the local Norwegian commander, Colonel Konrad Sundlo, funding for these batteries had never been approved in Oslo, the Norwegian capital. The only fortifications were a couple of blockhouses armed with machine guns, and these were obviously no match for the guns on the destroyers.

As the destroyers entered the fjord on the evening of April 8, all of this was unknown to the Germans, and there were tense moments as the ships navigated the narrow confines of the fjord. They would have essentially been sitting ducks for any determined resistance at this point.

The next morning, the naval flotilla sighted Narvik and prepared to land its troops—not knowing whether there would be resistance from the Norwegians who up until now had failed to respond to this violation of their neutrality. Just outside the harbor, however, the Norwegian coastal defense monitor Eidsvold engaged the German destroyers by firing a warning shot across their bows. The German destroyer Wilhelm Heidkamp responded by firing a spread of four torpedoes, two of which broke the back of the Norwegian ship. Eidsvold quickly sank, taking all but eight of its crew with it into the frigid waters of the fjord.

Inside the harbor a second monitor, the Norge, engaged the two German destroyers that were attempting to make it to the pier to disembark soldiers already assembled on deck. It took seven torpedoes to dispatch the Norge, but the result was the same and German destroyers proceeded to the docks, which were undefended from land.

The reason for the lack of dockside defense was that Sundlo had failed to concentrate his forces quickly enough and they were still assembling in the town when the German forces quickly appeared on the scene. Sundlo was in the process of moving from one post to the other in the town when he ran into General Eduard Dietl, commander of the 3rd Mountain Division, at the head of a company of German soldiers. After a brief negotiation and seeing the vulnerability of the civilian population and his own forces’ unpreparedness, Sundlo surrendered the town to the Germans without a fight. Some of his forces managed to escape across a railroad bridge into the hills, but essentially the fight for the town itself was over before it began.

The Germans were not to hold it for long.

The British Naval Forces Respond Quickly

Despite the German successes on land, at sea the precariousness of their situation began to manifest itself. The destruction of the Glowworm on the 8th had alerted the British naval commanders about the presence of the German naval forces in the Narvik area, and British military assets were being assembled to deal with the threat they posed.

The German commanders also knew it was only a matter of time before strong British naval forces arrived on the scene. However, several factors delayed the departure of the German destroyers from the Narvik area. Some of the destroyers had developed mechanical problems on the trip from Bremen, and all of them were low on fuel after having fought the rough seas of April 7 and 8. Finally, there was a need to cover the remaining supply ships that were still unloading in Narvik harbor.

Therefore, on the morning of April 10, the destroyers of the German invasion force were scattered about the fjord making repairs or refueling. One destroyer, the Diether von Roeder, was on picket duty at the entrance to the main part of the fjord but it left its post at first light without waiting for relief. This provided an opening for the five destroyers of the 2nd British Destroyer Flotilla under Captain B.A.W. Warburton-Lee to enter the fjord undetected.

The force quickly headed for Narvik harbor and upon entering the crowded estuary shot up everything in sight. In short order, the British turned the German flagship, Wilhelm Heidkamp, into a flaming wreck. The Anton Schmidt was hit by two torpedoes, broke in half, and quickly sank. The Diether von Reoder also paid for its mistake of leaving station, by severely damaged and essentially immobilized in the harbor. The attack also sunk or disabled 14 merchant ships of various types. Within an hour, Warburton-Lee’s force had destroyed most of the shipping in Narvik harbor.

The Germans Turn the Table

The other German destroyers, however, were not in the harbor itself but rather in various arms of the fjord. As the British destroyers withdrew up the fjord, the tables were turned against them. Two German destroyer squadrons emerged from their hiding places among the cliffs surrounding the narrow waterway. Accurate German gunfire quickly crippled the British flagship, Hardy, killing Warburton-Lee, and the ship was forced to beach. The destroyer Hunter was immobilized by German shellfire and rammed by the next ship in line, causing it to immediately sink.

Finally, the destroyer Hotspur received seven direct hits, which resulted in its eventual beaching as well. The last two British destroyers, although damaged, were able to withdraw to the open sea because the German destroyers, still not completely replenished, did not have the fuel to pursue them.

The attack by Warburton-Lee did achieve one critical strategic effect. It once again delayed the departure of the German naval forces. The immobile Diether von Roeder, sitting in Narvik harbor, was not going anywhere for a while. Furthermore, the German naval commander, Commodore Friedrich Bonte, was killed aboard his flagship in Narvik harbor. All of these factors made sure that the remaining German combat ships were still in the Ofotenfjord on April 13 when the battleship Warspite led a force of ten destroyers up the fjord.

Coupled with the damage suffered by the German force due to Warburton-Lee’s attack on the 10th, the German forces were now also critically short on ammunition. Despite the advantages that the smaller destroyers had in the narrow confines of the fjord, they were clearly at a disadvantage against the much larger guns of the Warspite. Within a short period the German destroyers had largely expended their ammunition and were either sunk or scuttled to prevent their capture. Their torpedoes did manage to severely damage several of the British destroyers, but the ultimate outcome of the one-sided engagement was never really in doubt.

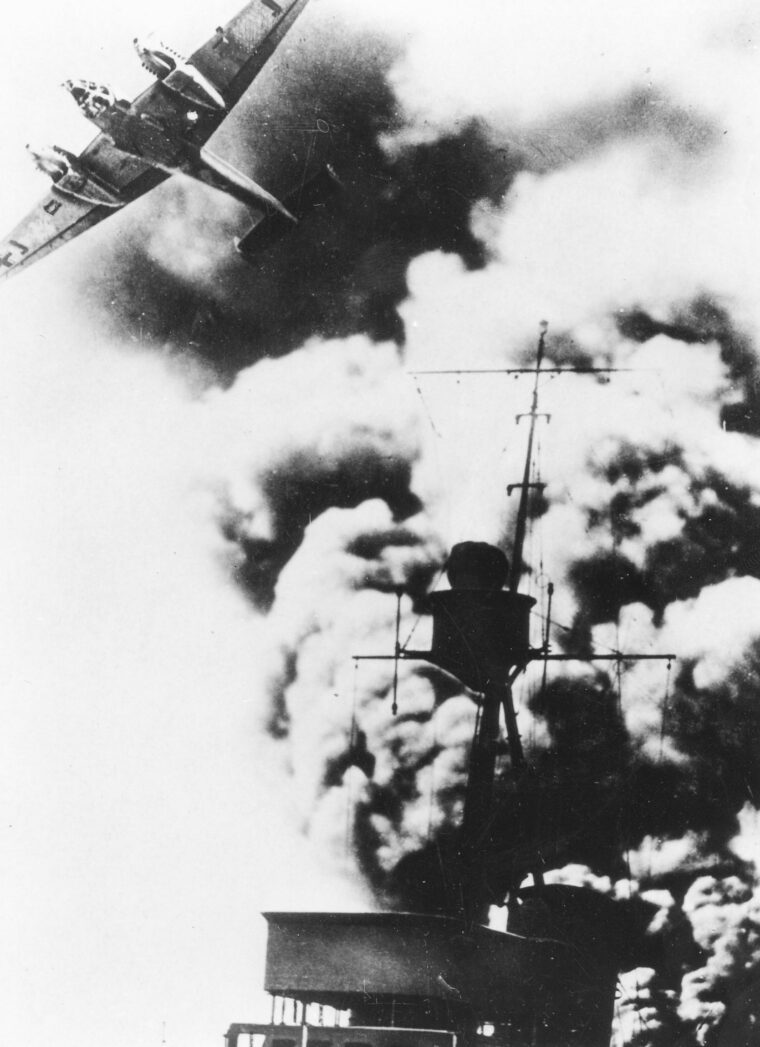

In a preview of the future, the withdrawing British ships were attacked by German aircraft operating from the newly captured airfield at Trøndheim, almost 400 miles to the south. The destruction of the German destroyer force, however, marked the beginning of the almost total control of the sea that the British were to enjoy for the rest of the campaign.

Dietl’s Land Forces Face Formidable Challenges

Their destruction also left Dietl’s forces in a precarious position. Although their manpower was augmented by the surviving sailors from the destroyers, much of their equipment and supplies had never arrived and were unlikely to make it past the fully alerted British forces at sea.

The only resupply from this point forward would have to come from airdrops or the landing of seaplanes in the fjords or on ice-covered lakes. The 1,750 men of the 3rd Mountain Division and the 2,700 naval personnel of the Narvik invasion force were essentially on their own.

To compound their difficulties, the airfield at Bardufuss, which was to be a key part of their operations, was not serviceable because it was still covered by nine feet of snow. This issue was largely to become academic as German forces probing northward ran into forces of the Norwegian 6th Division under Maj. Gen. Carl Gustav Fleischer, about 20 miles north of Narvik in the village of Lapphaug, and were held there by two Norwegian battalions.

Along the railway to the east, German forces ran into a blocking force which had retreated from Narvik with approximately 250 men. The Norwegians blew a key bridge and were able to hold out at Bjornfell, the border post to Sweden, until April 16 when they were driven across the border and interned. With the capture of Bjornfell, the back of the Germans was secured, and a key communications link to the outside world was established. In addition to some illegal reinforcements, medical personnel and non-military equipment were transferred through Sweden. The link also allowed Dietl to evacuate his wounded from the battle area.

With these victories, Dietl’s force was faced with defending an extended front in a daunting Arctic landscape with mountains rising as high as 9,000 feet in some places. Despite the very deep snow cover, it was almost impossible to concentrate on a narrow front because of the myriad opportunities that the landscape offered for flanking maneuvers.

The German force was also compelled to defend several key fixed positions such as the port in Narvik and the railway into Sweden, sacrificing its tactical mobility. Finally, even before the British and French landings, Dietl’s force was outnumbered by the Norwegian troops in the area, making it extremely difficult to close off all avenues of approach.

Supply Problems Plague the German Force

Efforts by the Luftwaffe to reinforce and supply Dietl’s cut off forces were haphazard at best. A typical story in the attempted resupply was that of the 2nd battalion of the 112th Mountain Artillery Regiment, which was ordered on April 11 to embark with four 75mm howitzers and 60 men for Narvik. The men and equipment were loaded into 12 Junkers Ju-52 transport aircraft and left from Berlin the following day. After a two-day journey, the planes finally arrived over the Ofotenfjord under low cloud cover.

Flying low, they were spotted by British naval units patrolling the fjord, and three planes were shot down by anti-aircraft fire. The remaining planes were forced to land on a snow covered frozen lake without any ground control. The weight of the planes cracked the melting ice, and none were able to take off again. While some of the equipment got through, all 12 Ju-52 transport planes were lost.

Poor planning ensured that the German troops were also inadequately supplied with all manner of equipment and goods for fighting in the inhospitable climate, which was still covered in deep snow in April and May. There were shortages throughout the German force, including a lack of heavy weaponry, ammunition, and basically anything the original landing force did not carry on its backs.

The naval personnel were in even worse shape. They were only armed through the capture of a Norwegian depot north of Narvik in the days following the capture of the city. Finally, and perhaps most perplexing, despite their role as mountain troops, most of the men of the 3rd Division did not even have adequate winter weather gear.

Improvisation was, therefore, the name of the game for Dietl’s forces. Guns and munitions were stripped wherever possible from the beached destroyers. Guns were also removed from other ships in the harbor, including 10 large 105mm cannon from five captured ore freighters. Radios were also salvaged during the days following the destruction of the destroyer force.

Difficult Conditions for Both Sides

Conditions for the defending forces were grim. Snow still covered much of the area, especially at higher elevations. Defensive positions were hacked out of the snow and bedrock wherever possible. The lack of pre-existing Norwegian fortifications, which had been so lucky for the invasion force in the original attack, now turned against the Germans. Without strong fortifications, the Germans were completely unable to control the approaches in the fjord. This basically ceded control of the seaways to the British despite limited German control of the air. The fact that the British were able to cruise the fjord with relative impunity exposed German defensive positions to harassing fire from Royal Navy destroyers.

This is not to say that the British had an easy time of it. Over the next few months, they were to suffer repeated attacks from German aircraft stationed to the south. In the confines of the fjord, there was limited room for maneuver when the Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers came down in their steep dives. German air power, however, was necessarily limited by the distances involved and the demands for the Luftwaffe to participate in the invasion of France and the Low Countries, which started on May 10.

Ultimately, it was the pace of events in the more central theater of France that would dictate the outcome of events in Norway. The diversion of German forces to France and the Low Countries dictated that the 3rd Mountain Division would be essentially on its own for much of the campaign but it also limited the number of ground troops available on the Allied side.

The British Launch an Offensive to Oust the Germans

On April 15, the first British landings occurred in Harstad on one of the side fjords off the main Ofotenfjord. Geographically speaking, this landing did not pose a major threat to Narvik itself but provided a logistical base for future operations. Over the following weeks, forces from Harstad began probing attacks along the northern shore of Ofotenfjord. Because the Germans were able to mount a more in-depth defense of this area due to the inhospitable terrain, Allied attacks, launched primarily by British and French mountain troops, were unable to push past the village of Bjerkvik, less than halfway between Harstad and Narvik.

The British were also hampered by the chaotic situation at Harstad. Confusion in the weeks leading up to the landings caused some equipment to be shipped to the units fighting further south around Namsos, and some material destined for Namsos wound up in Harstad. Guns and their ammunition sometimes became separated by hundreds of miles of rocky coastline. Other equipment had been badly packed and was damaged or made unusable during the transit from England.

A final issue that undermined the British ability to quickly overwhelm the Germans in the area was the division of command between army and navy commanders and the replacement of the army commander, General Pierse J. Mackesy, in the middle of the campaign. This situation was compounded by the fact that the army and navy commanders were also given separate and often contradictory sets of orders.

Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, had given the naval commander, Lord Cork, instructions that led him to favor a risky, direct landing in Narvik in an attempt to overwhelm the disorganized German defenders as early as April 14. Mackesy’s orders, coming from the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Lord Ironside, were far more cautious in nature and mandated the establishment of the base at Harstad before commencing probing attacks toward Narvik. It was in this spirit that Mackesy started his attacks along the northern side of Ofotenfjord in coordination with Norwegian forces in the area.

The landings between April 25 and 28 near Ballangen and Haakvik, on the southern side of the fjord, posed a more immediate threat to the German forces in Narvik. Haakvik was a mere 18 kilometers overland from Narvik. The distance to the southern side of the Beisfjord was less than 5 kilometers, and any emplacements along the Ankenes cliffs would dominate the town itself. English and later Polish forces began to test the German defenses in this area within the next few days.

Although Stretched, the Germans Hang On

Despite the fact that this was the most exposed area of the German defenses and at the same time critical for the defense of the town itself, Dietl could only spare two companies of men to defend a front stretching for miles along the rocky cliffs. Resupplying the 8th Company, the most exposed of the two units, was a tricky business that involved rowing across the Beisfjord under constant danger of interception from British naval units patrolling the area. Those same units regularly tossed shells into the German positions exposed along the top of the cliffs.

To make matters worse, the two German companies could not possibly hope to defend the entire length of the Beisfjord and so had to concentrate on key points, leaving much of the coastline undefended except by the extreme terrain. The 8th Company was concentrated on the area immediately opposite Narvik, while the 9th Company guarded the critical passage of the rail line at the very tip of the fjord.

The two companies were not in physical contact with one another, and yet the Allied forces failed to take advantage of this and their control of the sea to bypass the German defenses. The British could have successfully launched an amphibious flanking maneuver between the two companies and across the Beisfjord. This would have put them astride the German lines of communications, cut off all forces on the southern side of Beisfjord, and immediately threatened Narvik itself with land-based attack.

Typical of the tactical lapses that undermined Allied efforts in the Narvik area, this lack of initiative was a critical factor in the ability of the German forces to hold out as long as they did given the overextended nature of most of their positions. British and Polish forces spent the better part of May hammering directly at the German defenders south of the fjord. The Germans did manage to hold on by their fingernails.

In addition to maintaining their established defenses, the German troops were able to assemble scratch forces of ski troops and harass Allied soldiers based at Haakvik. These attacks convinced the Allied commanders that the forces in front of them were stronger than they actually were. After all, if the Germans were so weak and stretched out, how could they possibly be attacking? Dietl counted on this psychological effect to prevent the British from simply outflanking the isolated pockets of German resistance.

In the north, Norwegian forces, joined by the British advancing up the coastal road from Skanland and eventually French mountain troops, spent the next several weeks slowly pushing the Germans south across the arctic landscape. Even though the French troops were nominally mountain troops trained to fight in the Alps, they were unable to make significant progress through the six- to 10-foot snow drifts and periodic blizzards that covered the area. Only the Norwegian forces seemed able to make any headway across the difficult landscape.

The Germans, despite harassment from the British fleet, were able to bottle up British forces and French Foreign Legionnaires fighting along the coastal road near the village of Bjerkvik.

This stalemate to the north of Narvik persisted until the middle of May. Despite being heavily outnumbered, the Germans were able to muster the bulk of their forces in this area, and the terrain made it possible for Dietl’s mountain troops and sailors to stall advances from the Norwegian, French, and British forces probing toward Bjerkvik.

The situation was beginning to change further south, however. On May 2 and 3, the other British expedition to Norway around Trondheim withdrew, allowing the Luftwaffe to concentrate its efforts on the forces surrounding Narvik. Several ships were sunk or damaged in the fjords, while land forces were driven to ground by repeated and intense air attacks.

Claude Auchinleck Takes Command of the Situation

The British High Command, impatient with the slow progress of the Narvik expedition, replaced Mackesy with Lt. Gen. Claude Auchinleck, later to gain fame as commander of the British forces in the Middle East, on May 13. Auchinleck had already been in the theater for several days before assuming command and quickly sized up the situation. He was hampered by the continuing diversion of his forces to the south to stop the advance of the German relief column from the Trondheim area.

By the time he assumed command, Auchinleck essentially only had a division and a half of French forces and a brigade of Polish forces along with the complement of Norwegian troops, who were becoming increasingly suspicious of British intentions after all of the withdrawals in the south.

Auchinleck saw that advancing across the tough terrain offered little hope for a quick success. He also knew that time was not on his side with the Germans advancing up the coast and the invasion of France having begun on May 10. He determined that his best course of action was to use his advantages at sea and engage in a series of amphibious landings to bypass German pockets of resistance, such as the blocking positions on the road along the northern edge of the Ofotenfjord between Bjerkvik and Narvik.

The British had control of the fjord and also had the services of a large number of Norwegian fishing boats called puffers. These had been used to shuttle forces across Ofotenfjord in late April and now Auchinleck proposed to use them to speed up the advance on Narvik itself.

The Allies, now primarily French, Polish, and Norwegian since most of the British troops had been sent south to contest the German advance, still had most of their forces concentrated on the north shore. So, this effort received priority over the holding actions now taken by Polish forces in the Ankenes region.

Allied Amphibious Landings Wreak Havoc on the Germans

Dietl could hold off the attacks across land, but he had no answer to the seaborne operations. The first attack on May 12 bypassed the German blocking positions in Bogen and landed instead at Bjerkvik, Elvegaard, and Öyjord. Two battalions of Foreign Legionnaires landed in Bjerkvik and Elvegaard, where they recaptured the Norwegian Army depot that had been so critical in resupplying the German northern front.

This attack also cut off the German forces defending the road between Bogen and Bjerkvik and forced them into a hasty retreat, pursued by Polish units and Norwegian ski troops. These Germans were in danger of being entirely cut off by Norwegian and French forces advancing southward from Gratangen toward Bjerkvik. However, the Germans were able to withdraw to the Kuborg Plateau north of Björnfjell and assist in the defense of the vital rail link to Sweden.

The landing in Öyjord threatened Narvik itself as it lies just a few hundred yards across Rombaksfjord from the Narvik peninsula. Simultaneous attacks by Polish forces on the Ankenes peninsula to the south brought Allied troops to the shore of Beisfjord from Narvik in the south. Dietl’s perimeter had now shrunk to an area immediately north and south of the railway line from Narvik to Sweden, with the British threatening amphibious landings on either side of the Narvik peninsula at any time.

The British had accomplished this relatively rapid advance because their overall supply situation in the north had improved. The amphibious operations were supported by aircraft operating out of the incomplete airfield at Skaanland as well as, weather permitting, the field of Bardufoss, which had recently been cleared of snow. In addition, the British aircraft carriers Ark Royal and Glorious were also able to supply planes to the fight.

The result was that for the first time in the battle the Royal Air Force was able to achieve a measure of air superiority over the contested area. Coupled with the control of the sea, these advantages were simply too much for Dietl to effectively counter. Once the British got over their fear of amphibious landings, Dietl’s fate was sealed.

On May 28, the final assault on Narvik began with an amphibious assault across Rombaksfjord by French troops. After a brief fight on the beachhead, they advanced swiftly into Narvik itself, which had largely been abandoned by the Germans, who retreated deftly up the rail line toward Björnfjell. Norwegian forces threatened the Björnfjell position from the north, and the only avenue of retreat was into neutral Sweden and internment.

Despite Successes, Allies Withdraw from Norway

Despite the loss of Narvik and the precarious position of his remaining forces, Dietl had technically won the battle by holding as long as he did. Even before the first troops marched into Narvik, the decision had been made to abandon the Allied expedition. Events in northern Norway had been overshadowed by events in France.

By May 28, German Panzers were on the Channel coast, and the evacuation at Dunkirk was underway. The British home islands were practically undefended, and the forces tied up in Norway were desperately needed to defend the homeland. In addition, the resolute advance of German mountain troops from the south across seemingly impassible terrain had overwhelmed British and Norwegian blocking positions time and again and was within 100 miles of Narvik.

Instead of accepting the surrender of Dietl, Norwegian General Otto Ruge visited his headquarters in Björnfjell on June 7 to negotiate the surrender of the Norwegian forces in the area. The Allied troops were evacuated in a hastily arranged convoy. The final chapter in the Narvik drama saw the British carrier Glorious, while evacuating the planes from Bardufoss and Skaanland, sunk by the German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. The two German battlecruisers subsequently missed the heavily laden troopships carrying the Narvik force back to England.

Two Amphibious Campaigns; Two Very Different Results

The Narvik campaign marked the first and last time that the Germans attempted a major amphibious operation in World War II. There were some minor operations along the Baltic Coast, but these were done against the ineffective Soviet navy. The Norwegian campaign marked the high point of the German surface navy’s operational capability in World War II. The losses in surface ships and, more importantly, the loss of confidence in the face of the Royal Navy, ensured that German surface naval efforts in the Atlantic would be confined to raiding.

The precariousness of Dietl’s position illustrated the dangers of a relatively unsupported amphibious operation all too clearly to the German High Command and may have contributed to the decision to call off Operation Sea Lion, the planned invasion of Great Britain, in September 1940.

On the other side, the British were able to test their amphibious capabilities in a limited manner, and the campaign allowed them to somewhat allay their fears of another Gallipoli, the disastrous World War I attack on the Dardanelles. Despite serious losses from German air attacks, the Royal Navy was able to gain valuable battle experience and was much more capable of absorbing those losses than its adversary.

If the British had directly assaulted Narvik early on as Lord Cork wanted, Dietl’s force might have been overwhelmed before it was able to consolidate its hold on the area. Dietl would not have been able to salvage the heavy weaponry he found in the area in time and certainly would not have had time to dig the fortifications that would hold up Allied forces in the next month. The quick elimination of Dietl’s force would have dramatically changed the strategic situation in the north of Norway, as the Allied forces could have concentrated on stopping the German mountain troops advancing from the south.

By the time Auchinleck’s forces had recaptured Narvik, the strategic situation for Britain looked bleak with the imminent fall of France, and it is no surprise that British forces in Norway were withdrawn at that point. In hindsight, the forces withdrawn from Narvik made little difference in the ensuing Battle of Britain, especially since all of the aircraft evacuated went down with the Glorious.

It is intriguing to think what might have happened if the British and Norwegians had managed to hold on in extreme northern Norway. It would have taken fairly small forces to keep the Germans from advancing up the peninsula, especially with British control of the sea.

In the short term, this resistance would have deprived the Germans of the valuable Swedish iron ore coming through Narvik. Over the long term, this would have also deprived the Germans of valuable naval and air bases, which were later to harass the arctic convoys to Russia after June 1941.

German surface forces sheltering on the fjords of northern Norway were to be a constant threat until the last remaining raider, the Scharnhorst was sunk in late 1943. The long-term geopolitical implications of an Allied presence in northern Norway might also have influenced the Finnish decision to enter the war on the German side in 1941 and attack Russia.

Author Tom Haymes is on the faculty at Houston Community College and has published numerous articles on military history and international affairs. He is currently working on a book on capitalism and nationalism entitled Evangelical Capitalism. He lives with his wife and two children in Katy, Texas.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments